Take 5: Favourite Films from Before I Was Born

It’s only natural to feel an affinity for the films you grew up watching from childhood into your teenage years. You had more time to watch them over and over, and many introduced you to crazy new ideas for the first time.

Such childhood favourites tend to evoke strong feelings long into middle-age, just ask the average Star Wars fan. Even objective bad movies can hold a cherished place in one’s heart, simply because your tastes were less sophisticated and you gleamed something from them.

But as one grows more mature and develops a wider perspective, it becomes more likely you’ll want to experience many films released before you appeared on the planet. It’s not like there’s any kind of fixed barrier to entry (many childhood favourites were likely made before your birth anyway), but curiosity will often inspire you to seek out stuff released decades before your time. The kind of films your grandparents or even great-grandparents would have gone to see at ‘the pictures’.

Older movies reveal the seismic changes in how films are made and presented. One can explore films where colour (or even sound) didn’t exist yet; eras when women and minorities had to fight for good leading roles; times when characterisation was a priority over spectacle; or when the idea of a cutting-edge VFX involved stop-motion figures.

And it’s possible to even prefer films made before you were born! They likely offer a vastly different experience that may suit your tastes better than today’s more bombastic offerings. Or it’s just fun that even a humdrum classics can eventually become a fascinating time capsule of old fashions, music, design, and culture.

Below, six of our writers have written about their favourite film released before they were born, then nominated some runners-up. Have you seen most of these? Leave a comment with your own choices below, we’d love to read them.

Made between his cultural landmarks, The Godfather Part I and II (1972, 1974), Francis Ford Coppola‘s understated lonely-man thriller The Conversation (1974) might be the less instantly recognisable of his 1970’s oeuvre, but it’s no less significant. A film equally as anxious about alienation and technology, The Conversation blends the two into an inseparable tangle of post-Watergate angst. Tapping into a growing societal distrust of the people in charge and unwieldy new technologies, Coppola’s film presents a flipside to the idealistic notion of American Invention, where portable audio and video recording doesn’t provide us so much with a view to a new world, but rather, a dark avenue of isolation and obsession.

As surveillance expert Harry Caul, Gene Hackman is understated and withdrawn, a man tumbling downwards into a conspiracy he’s too close to fully understand, as exemplified in the film’s shockingly clever coda. But more than the twisty plot and cultural relevance, it’s the film’s desperate melancholy and quietly shattering yearning that sets it apart from others of its kind. Not unlike the act of watching a film, Harry views flickering lights through screens and hears transmitted voices through cables and wires, connective yet somehow desperately lonely. Like the surveillance recordings spooling endlessly, Harry and the viewer turn in circles, chasing our tails, searching for answers in the darkness.

Honourable mentions: Stop Making Sense (1984), The American Friend (1977), Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960), and A Face in the Crowd (1957).

As a lavish attempt by Warner Bros. to compete with the epic historical drama Gone With the Wind (1939), All This, and Heaven Too wasn’t as successful at the box office. With a story set against social upheaval in Paris, it’s a moving tale based on a bestselling novel about the fictionalized circumstances surrounding a real-life murder-suicide scandal that took place in 1847, focusing on governess Henriette Deluzy (Bette Davis) falling in love with her employer, the unhappily married Duc de Praslin (Charles Boyer).

The film focuses on the romantic tension between the leads and is an emotional, hand-wringing, soul-connecting romance. They never kiss, never say ‘I love you’, but by looks and pregnant pauses alone Boyer and Davis deliver an amazing amount of angst and passion. It’s peerless melodrama, with Henriette and the Duc constantly denying their feelings for each other and attempting to keep up the facade of their friendship. The tension is maintained throughout, augmented by the actions of the Duc’s spiteful, abusive, and obsessive wife (Barbara O’Neil, deservedly nominated for an Academy Award).

All This, and Heaven Too is a perfectly acted and perfectly pitched drama and one that captures the appeal and enchantment of old-fashioned Hollywood cinema storytelling.

Honourable mentions: Singin’ in the Rain (1952), Cat Ballou (1965), The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967), and The Sound of Music (1965).

The Bride of Frankenstein always stuck out above Dracula, The Mummy, or The Wolfman. Was it because of Franz Waxman’s emotive music? Maybe Kenneth Stackfaden’s mesmerising laboratory sets and John F. Fulton’s impressive rotoscoping of miniatures interacting with life-size actors? Under James Whale’s direction, it all helped created a monumental experience, but what impresses me most is how ahead of its time The Bride of Frankenstein was. It’s now seen as one of the great sequels.

Naturally so, as Bride adapts material from the second half of Mary Shelley’s novel that Whale didn’t use in Frankenstein (1931). Every character organically evolves from their last encounter: the Monster is just as dangerous (killing the grieving parents of a drowned girl) but he learns English and develops a cunning that threatens his creator. Meanwhile, Dr Frankenstein, who hides like a war criminal evading his actions, faces consequences in his old mentor forcing him to create the titular Bride.

Whale completed his Frankenstein duology with Bride but Boris Karloff‘s creature wouldn’t stay dead. Universal made crossovers with Dracula, the Wolfman, and even double-act Abbott and Costello. Back in 1935, witnessing the impeccable continuation of a story and the beginnings of a cinematic universe must have been breathtaking.

Honourable mentions: Ed Wood (1994), Phenomena (1985), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974), and Mary Poppins (1964).

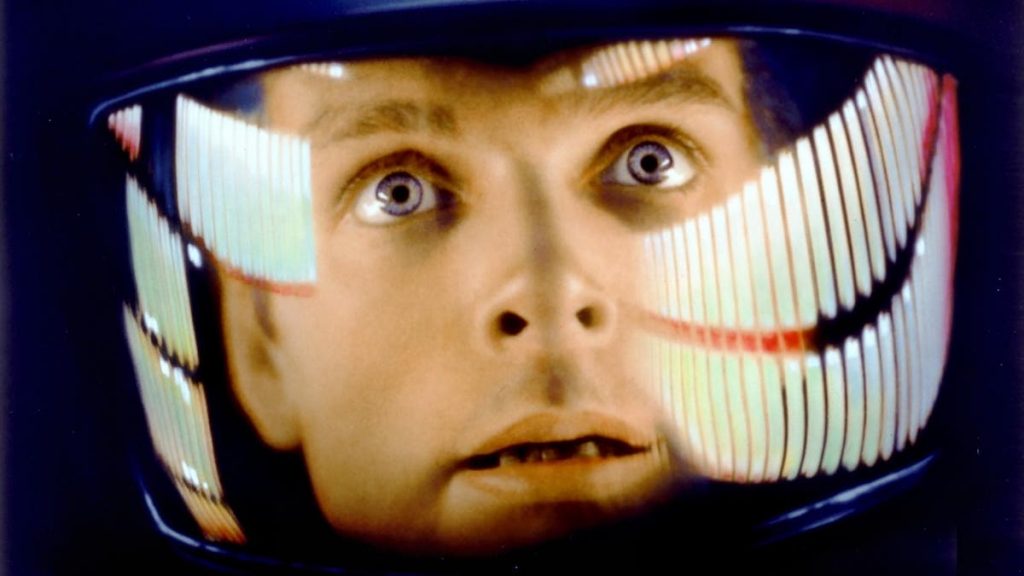

Stanley Kubrick‘s epic 2001: A Space Odyssey is a bonafide masterpiece. I’m a sucker for a good science fiction story and this one comes from the great Arthur C. Clarke‘s pen. And when two geniuses of their respective art forms collaborate, is it any wonder a classic was the end-result? It’s difficult to say exactly why 2001 speaks to me because it’s not an easy watch; it’s meticulously presented but ponderously slow, and it has a bizarre ending that confuses just as many people as it enthrals. But, for me, it’s the closest cinema has come to delivering a “religious” experience.

The opening sequence is my favourite section, with the ‘Dawn of Man’ presented by a group of primates learning (or being influenced by an alien intelligence) how to manufacture weapons in which to kill for good, but ultimately murder to ensure their dominance. The moment when a primate throws a bone into the air, which becomes an orbiting spacecraft millennia later, is deservedly hailed as the best match-cut in cinematic history. It says so much in seconds, covering aeons of time in the process. Other moments are equally as indelible (like the dulcet tones of HAL the computer), and I’m astonished that 2001′s VFX (by the great Douglas Trumball) have barely dated in all these decades. Simple techniques and in-camera trickery just don’t age; if it worked, it’ll always work.

2001: A Space Odyssey remains the benchmark for science fiction at the movies, and tackles enormously weighty themes in a way that connects to your soul. Complaints about its lack of emotion are understandable (although even this seems intentional, as evolution has brought us to that point), but too much about 2001 connects to some primordial part of my brain obsessed with knowing where we came from and where we might be headed as a species.

Honourable mentions: Vertigo (1958), Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory (1971), Jaws (1975), and A Clockwork Orange (1971).

Lawrence of Arabia is that peculiar thing, a film very much of its era that also stands the test of time. In 1962, Britain was coming to terms with the end of its Empire and the emergence of new relationships with its former subjects. David Lean’s movie about the Arab Revolt of 1916-18 is set in the falling years of the Ottoman Empire and deals with an Englishman’s attempts to forge a different, non-colonial kind of relationship with an exotically colourful people.

Cinematically, too, Lawrence of Arabia looks not only back to the great historical epics of the 1950s, but also forward to the age of the anti-hero.

Peter O’Toole’s T.E Lawrence is a strange emptiness at its core, as compelling yet difficult to interpret as the Arabian desert. And, as with Lawrence’s real life, there’s an unexplained heart of darkness, represented in the film by his sinister encounter with José Ferrer’s Bey of Deraa.

It’s these thematic elements, surely, that give Lawrence of Arabia its lasting power. What makes it work while you’re watching it, however, are the gorgeous desert photography, the unhurried pace that has a sweep of grandeur equalling the landscape, the big set-pieces like the Arab attack on Aqaba, Maurice Jarre‘s score with its melding of plucky English catchiness and Middle Eastern mystery, and the supporting performances from the likes of Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, and Omar Sharif.

Even by the end of this nearly-four-hour film, we understand almost nothing about Lawrence, but we do have a sense of what he loved in Arabia and the Arabs. The film is ostensibly about the man, but it’s surely as much about the people, and indeed it reaches beyond that. In being about the Middle East, it tells us a lot about the West too. In being about 1916-18, it tells us much about the century to come.

Honourable mentions: The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948), Dead of Night (1945), and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1931).

George Lucas handed the reigns of his Star Wars sequel to his mentor Irvin Kershner, who gave things a darker tone and more character depth. The Empire Strikes Back (1980) had audiences queueing for hours, only to be stunned by the ultimate cliffhanger ending. All of the original cast returned, but they’d grown into their roles since 1977. Mark Hamill did a particularly great job portraying the emotional turmoil of Luke Skywalker as the Tattooine farm boy learning to use the Force with the help of Jedi Master Yoda (Frank Oz).

The VFX were also more impressive than before, looking spectacular even by today’s incredible standard. Whether it’s the stop-motion AT-ATs attacking the Rebel base on Hoth, or the Millennium Falcon navigating an asteroid field, they’re still a delight to the eye. John Williams‘ music is also just as powerful and magnificent, reprising themes from A New Hope but ensuring Empire‘s score is more nuanced and complex. He also introduces the classic “Imperial March” as Darth Vader’s Theme, which perfectly captures a sense of evil menace.

For four decades, The Empire Strikes Back has proven itself the ultimate movie sequel. So many other franchises trying to copy its example of taking things down a darker and more mature path. Empire stands tall as one of the great sci-fi adventures and best sequel ever made.

Honourable mentions: Dawn of the Dead (1978), Alien (1979), and The Lost Boys (1987), and Dr Strangelove (1964).