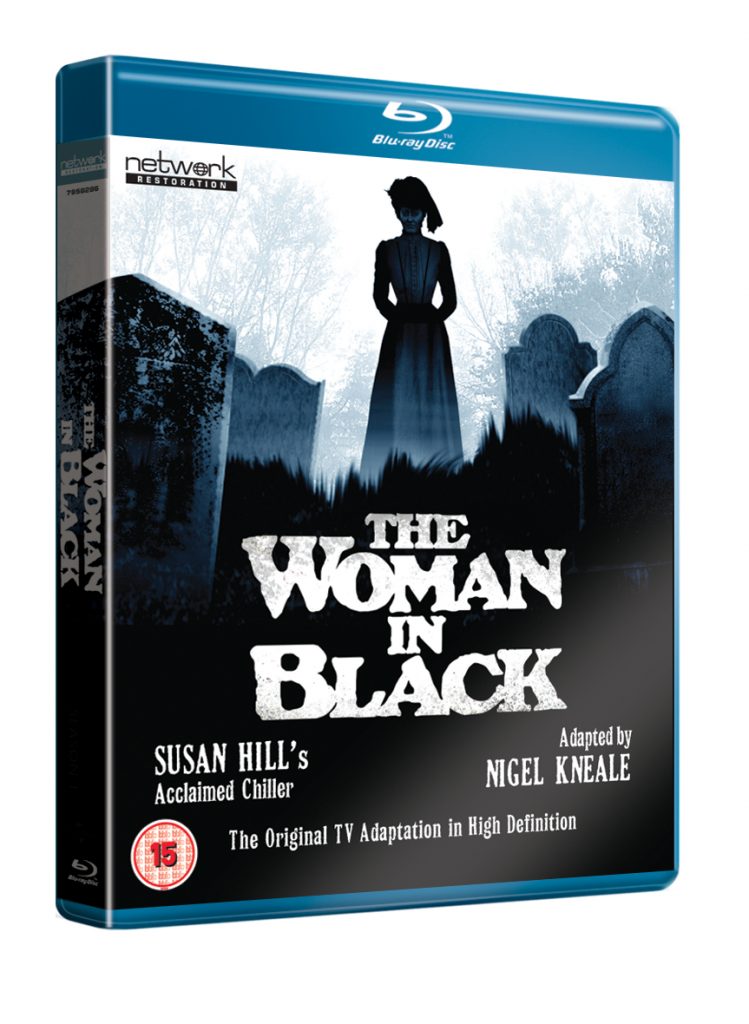

THE WOMAN IN BLACK (ITV, 1989)

A lawyer travels to a seaside town to settle the estate of a recently deceased woman, but becomes ensnared in something more sinister.

A lawyer travels to a seaside town to settle the estate of a recently deceased woman, but becomes ensnared in something more sinister.

Today’s audiences perhaps know The Woman in Black best through the 2012 film version, starring Daniel Radcliffe; a significant success that relaunched Hammer and spawned a 2015 sequel. So it’s beautifully apt that Radcliffe’s role in this 1989 ITV version, played by Adrian Rawlins, is an actor known for playing the father of Radcliffe’s Harry Potter character!

More closely based on Susan Hill’s novel than the 2012 movie (although Nigel Kneale’s screenplay also takes some departures), 1989’s Woman in Black often feels like a product of the 1970s or 1960s. Perhaps that was an intentional decision of director Herbert Wise (best known for the classic 1976 BBC series I, Claudius), given that it’s such an old-fashioned story in many ways. There’s a distinct flavour of M.R James’ writing, and the mission given to the lead character near the beginning of the movie has a whiff of Jonathan Harker’s in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Indeed, at moments The Woman in Black can conjure up an even earlier cinematic era. Consider how a document dropped on a train carriage floor is lit and shot, for example—it’s emphasised so that nobody watching could possibly miss what it reads, in a way that evokes a 1930s style of filmmaking.

The story starts in London in 1925 (a character refers to Chaplin’s The Gold Rush as being a new film), with a young solicitor and father called Arthur Kidd (Rawlins) dispatched by his irascible boss Sweetman (David Ryall) to sort out the estate of a dead client. And so off he goes to northeast England (even if some of the rural accents seem to belong to the other end of the country) and into a series of familiar genre tropes: ominous foreboding during the journey, locals in the pub who seem like they might have a secret, the lonely ride out to the isolated house…

Inside that house, we have more cliches: the locked room, the dolls, the shots down long corridors. For the most part, this is such well-trodden ground that it can hardly be said to be scary, or even dramatic. But then there are touches of genuine originality and, occasionally, disturbing power. For example, there’s the clever use of a wax-cylinder phonograph, on which Kidd records his thoughts. He may seem relatively rational, but much more unsettling are other recordings he discovers from the deceased client, apparently referring to a haunting, by a woman, in this very house (“Much tumult in the other rooms…I called out using her name…”)

What’s going on (or at least the outlines of it) is clear from early on. All the same, the climactic appearance of the titular woman in black has a highly effective nightmarish quality (even if it also evokes a funfair haunted-house ride), and there’s a brilliant use of sound both here and elsewhere.

Rachel Portman’s score can certainly be unnerving in itself, but it’s often the diegetic sound that brings The Woman in Black alive—like a great cut from a busy marketplace to a deserted and silent graveyard apart from a cawing crow. As so often in horror, it’s frequently what we hear but can’t see which is most impactful (like screams in the mist), and sometimes Wise emphasises this by simply showing us emptiness whenever a source of sound should be.

The Woman in Black ends with a truly magnificent twist, casting a ghastly shadow over a film which to that point might (for all its undoubted atmosphere) have seemed a little too much of a comfy period piece to be considered really dark.

Until then, there’s not only a well-told tale to enjoy, but also some fine character performances from Ryall, Bernard Hepton as a local bigwig, John Cater as a rural solicitor, and perhaps most of all William Simons in a small but striking part as Kidd’s driver. If they all essentially play variations on the same role (men familiar with the reality of the situation but reticent about it), nevertheless they contribute substantially to our growing sense of Kidd being alone in a dangerous place.

This is a TV adaptation of a mainstream writer’s novel with well-established genre antecedents, so it’s not surprising there’s nothing radical or subversive or demanding of the viewer. But every detail is well-crafted, the ’20s period is almost completely convincing, and even if the progress of the narrative is relatively easy to predict, there are enough surprises (and occasional shocks) to make it satisfying.

UK | 1989 | 100 MINUTES | 1.33:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

This restored and remastered HD version also includes an excellent audio commentary, chatty and informative on filmmaking minutiae.

director: Herbert Wise.

writer: Nigel Kneale (based on the novel by Susan Hill).

starring: Adrian Rawlins, Bernard Hepton, David Daker & Pauline Moran.