EX MACHINA (2015)

The helicopter blades whirling over greenery in the opening of Alex Garland’s Ex Machina are eerily, deliberately reminiscent of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park. The parallels between the two films don’t end there, with Garland’s sleek sci-fi three-hander predominantly concerned with identical themes of Spielberg’s adventure classic: humanity’s desire to create life that’s not meant to exist; the maniacal urge to push the boundaries of science, and the terrible, consuming temptation to put on a tunic and play God.

In Spielberg’s monster movie, so startlingly wondrous and wide-eyed, the disastrous denouement of these desires is rampaging dinosaurs threatening family life. In Garland’s elegant and introverted directorial debut, the disastrous denouement is Oscar Isaac dancing after several bottles of lager.

I think I might just prefer the latter.

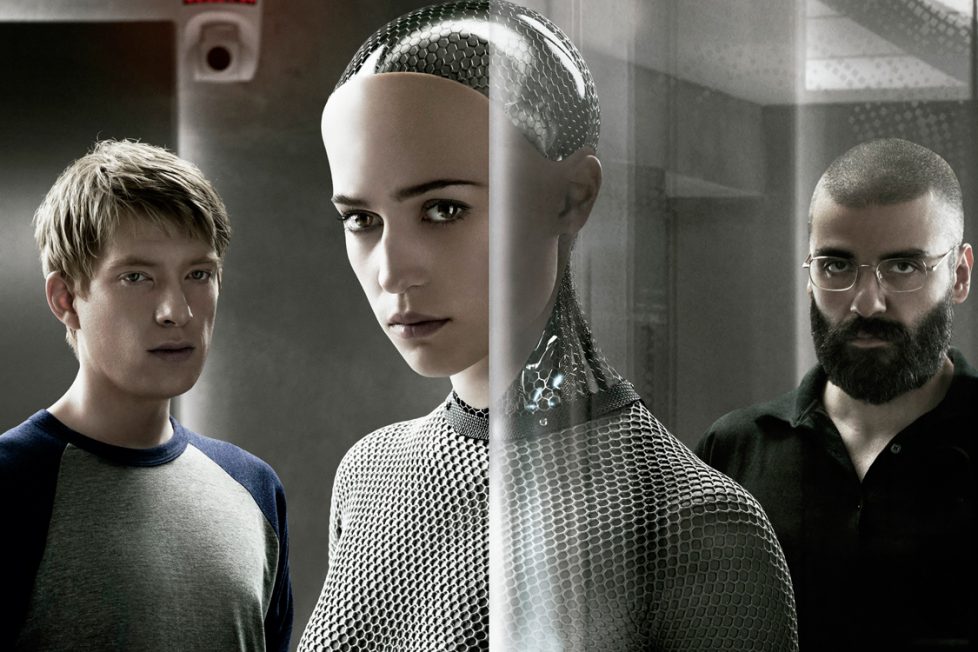

It isn’t dinosaurs being made on this island that Domnhall Gleeson’s character Caleb is flown into, though. After winning an office raffle, the 26-year-old computer programmer’s given the chance to experience his boss Nathan’s (Oscar Isaac) greatest achievement: a ridiculously advanced and devastatingly beautiful artificial intelligence. Nathan, the creator of this twitching, pretty android he calls Ava, is quickly established as a famed but reclusive genius with alcohol problems, a strong handshake, a hipster’s beard, and an ego the size of the island he owns. A kind of Zuckerberg via Williamsburg. Odious but odourless; a clean creep with perpetually bare feet.

Caleb has been invited to this Escher-esque “research facility”, full of spiralling steps and locked doors, in order to participate in a series of Turing Tests with the android Nathan’s developed. During the tests, Nathan monitors the communication patterns and blooming relationship between Caleb, powered by a giddy intelligence and Ava, (Alicia Vikander) who is powered by ‘Blue Book’, a fictional search engine which is cleverly utilised as the fountain of Ava’s knowledge.

Our incessant questioning online and insatiable need to know everything is hijacked by Nathan as a potentially lucrative vat of knowledge for the new life he’s cultivated. But more than that, using this search engine data (the search engine he invented and Caleb works for) as a “brain”, Ava is able to harness unique insight into how we gather knowledge and formulate individual thought, too (i.e. she understands the way we think, not just the things we think of).

It is that caveat, alongside her supreme understanding of civilisation, that makes Ava such a compelling twist on the twitching robot trope. She’s not only armed with facts and figures but with an ability to articulate statistics in poetic terms; to reason with them and rationalise an argument around them. That is to say Nathan’s creation is a computer that doesn’t just answer—it answers back. The curious thing is that he’s built that disobedience and outward-looking faculty in.

If he is playing God then he’s created an atheist.

Once all the science of search engines is understood, the duologues that Gleeson and Vikander embark on in their Turing Tests prove lucid and enchanting. Flighty conversations conceptualising what it means to think, live and be with Vikander stealing every scene with elegant but eccentric movement. Half TinMan, half Anna Pavlova. These scenes are almost all filmed from the prospective perspective of Nathan—always, you feel, watching on—tipsy but dangerous. Caleb and Ava speak quickly, with lips licked and heads hurting, and a pane of glass separating them.

But who’s in the zoo? Who is fawning and who is flinging shit? Garland leaves you hanging.

These scenes form the flesh of the film. They’re pure theatre. And though Garland’s natural novelistic tendencies and bombastic language occasionally collides with the sharper and simpler pop psychology on offer, the vermilion-lit Tests manage to ask the questions you want answered without conjuring up the kind of conclusion you expect.

Almost as if Garland is waiting for us to get on Google to find out the actual answer to the philosophical debates Caleb and Ava tumble in to. The rascal.

At times played with the humming hope of human-android lust beneath them, and during others with the brooding buzz of horror hiding in their corners, these “Tests” become pitstops in the piece, and it is Nathan’s dissatisfaction at one of them that forms the most sensational scene in the movie.

After Nathan jeopardises the blooming relationship between Caleb and Ava by tearing up a picture she’d drawn for him during the “Test”, which for Caleb calls into question Nathan’s intentions for them at all (what is science if not an excuse for more art, after all?) Caleb sets out to berate his boss—the thing that stops him from properly doing that is a devilishly choreographed dance of disco distraction from Nathan who “tears up the fucking dance floor” with bendy limbs and thick rhythm to “Get Down Saturday Night” alongside a suspiciously mute, troublingly subservient and frighteningly good female companion who follows Nathan around his glacier mansion—picking up glass and shuffling in silence.

And though Vikander is stunning throughout, it is this moment, this powerful dance, that seals the film as Isaac’s prize.

He plays Nathan as a majestic moonshine of burly intensity and crippling insecurity with neither characteristic ever totally outweighing the other—at once he is charming and despicable. At once he dances well and goofily. It seems no wonder that he appears in line to replace Harrison Ford as the Star Wars franchise’s resident loveable rogue—he’s a very appealing bastard, an utterly handsome prick.

Nathan is the latest in a run of performances by Isaac that gave established him as an artist of impeccable cool; and though Garland’s script and directorial decisions are not as fine-tuned as the Coen Brothers, or as brazen as Nicholas Winding Refn’s (the two other directors Isaac has shone with), there is enough here to suggest that the two may develop a professional partnership to be very excited about. The quiet, creeping cinematography and hushed, not rushed delivery of Isaac give the movie a voyeuristic vitality that made me crave more Garland-Isaac joints even if this one wasn’t perfect. We’ll see.

It is the first sight of Nathan that is most telling of Ex Machina‘s triumphs and problems though. The camera slides up behind him as he’s Ali shuffling on his balcony: puffing, panting, and jabbing at a punching bag that swings from metal like the gallows aftermath. In truth, Nathan is always fighting in this movie—with Caleb, with himself, with alcohol, with his “creations”, with his dance moves, and though it’s slightly heavy-handed, imagery of the genius-as-brawler is a neat way of capturing the atmosphere of this movie. It’s a movie that takes big swings, asks big questions, but can’t quite decide whether to think or thump its way to perfection.

In the end, like Isaac’s portrayal of Nathan’s boxing on the balcony, Ex Machina is beautiful and monstrous and oh-so-smart, but left wheezing at the size of its enormous task.

starring: Domhnall Gleeson, Alicia Vikander, Sonoya Mizuno, Oscar Isaac, Corey Johnson, Claire Selby & Symara A. Templeman