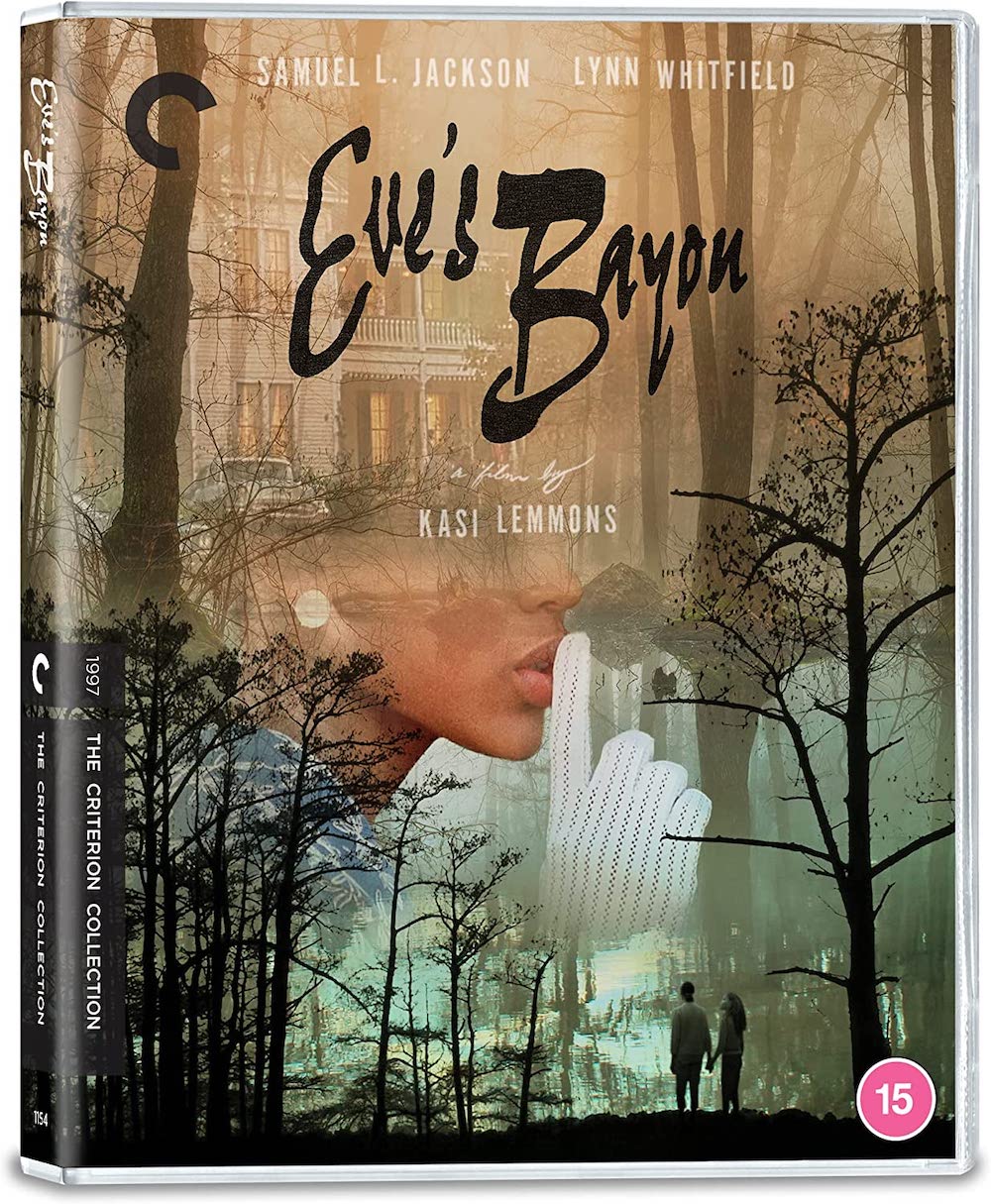

EVE’S BAYOU (1997)

A little girl witnesses something that haunts her about the powerful patriarch of an affluent family...

A little girl witnesses something that haunts her about the powerful patriarch of an affluent family...

In the 1990s, American independent cinema was in robust shape. Along with a surfeit of fresh young talent, a market was opening up which offered these filmmakers a chance not just to make their films, but to have them seen far and wide. Indie films were cool, carried by a carefully cultivated illusion they were the post-punk of filmmaking; that there were no men in suits between directors and audiences, and that what we were given was a pure distillation of auteur filmmaking.

Regardless of the truthfulness of the idea, the films and filmmakers who were sprouting up were hard to argue with. Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights), Quentin Tarantino (Pulp Fiction), Kelly Reichardt (River of Grass), Spike Jonze (Being John Malcovich), the Wachowskis (The Matrix) and David Fincher (The Game), to name a few, all debuted that decade. Meanwhile, the likes of Steven Soderbergh and Spike Lee held their independent-minded ethos well into the ’90s, even when the former’s work became evermore flashy.

But few directorial debuts of the independent boom feel quite as specific and purposefully out of step as Kasi Lemmons’ rapturous drama Eve’s Bayou. Captivatingly strange yet reverent to classicism, Lemmons helmed a unique hybrid that feels out of time: the 1960s remembered from the 1990s, perhaps. Or an old class of filmmaking filtered through a modern lens.

Lemmons was already a familiar face when she made the film. She’d had significant roles in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and Candyman (1992), and it was the year after the latter that she began work on the screenplay that would become Eve’s Bayou.

Set in 1960s Louisiana, the film follows 10-year-old Eve Batiste (Jurnee Smollett), the middle child of a wealthy family that includes her doctor father, Louis (Samuel L. Jackson), and mother Roz (Lynn Whitfield). To describe the film’s plot is to do it a disservice and to dilute its effect because this isn’t a film with a story, it’s a film about stories. Specifically, it’s a movie about the way in which stories change over time and how they cling or disappear.

Loosely, Eve’s Bayou centres on Eve as she learns about the world around her. Her voiceover from many years after the events of the film describe to us the land they live on, and how she takes her name from a creole ancestor who lived there. She had been a slave, bearing sixteen children, and as Lemmons’ camera drifts weightlessly along the smoky water and under weeping willows, we think that we might perhaps catch a glimpse of their ghosts if we look closely enough. The ghosts of the past, and of the future…

“The summer I killed my father I was ten years old,” she states. This is that summer, or are we seeing a summer even further back when her ancestor Eve lived? Or a summer many years later, fractured and retold from a memory filled with holes? That is the mercurial nature of the film, and it takes a vaguely sinister pleasure in both holding its cards close to the vest and laying them out entirely. She killed her father, we’re told. But as it unfolds, we cannot be sure of even that.

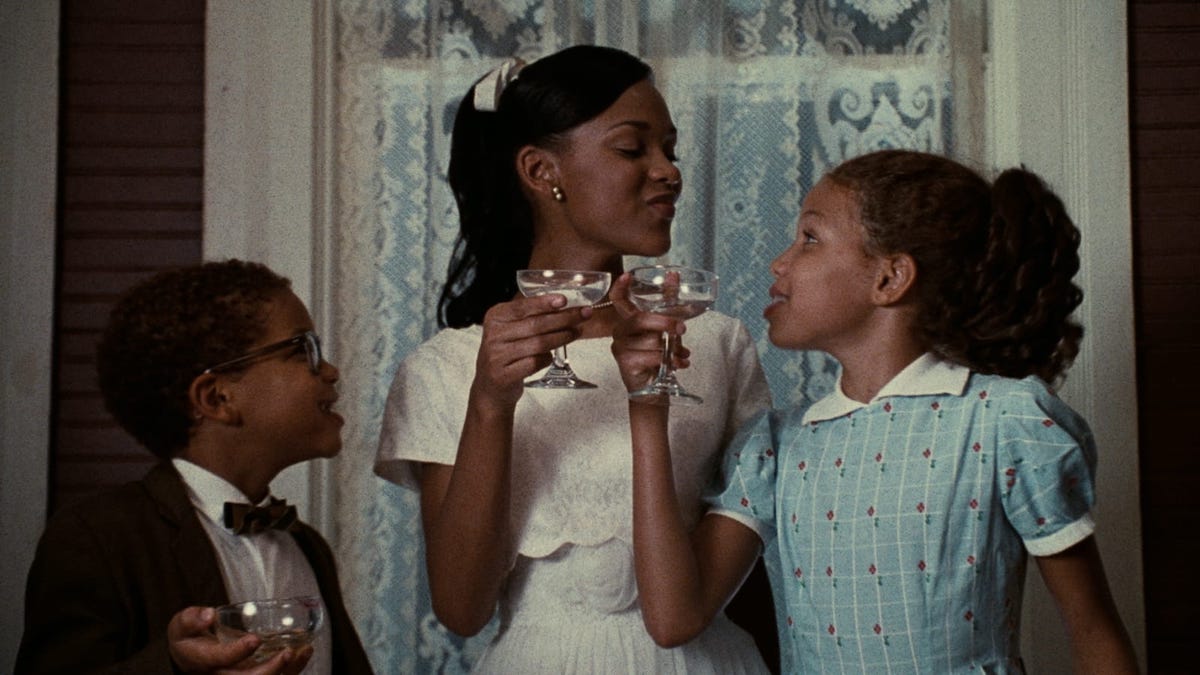

One night, towards the end of an elaborate party her parents are throwing, Eve sneaks out to the barn for some quiet. The adults are all drunk and loud, particularly her father when he stumbles into the barn with a friend of the family. Eve, watching fearfully, probably doesn’t understand everything she sees—what 10-year-old would? But she knows enough to know it’s bad and, after an unbelievable explanation from her father, she runs back to the house and tells her older sister Cisely (Meagan Good) of her father’s infidelity.

Many films concern themselves with the end of childhood, and the eroding of innocence. But few capture the exact moment a life crumbles, and the ways in which we try to piece it back together. Cisely tells her sister she’s wrong. She mistook what she saw, and it was perfectly innocent. Lemmons locks us in an intimate shallow focus with Cisely—she’s persuasive, she’s older than Eve, and she knows what she’s talking about. But the shadow of the evening looms large. As does the admission in the narration (the one of the killing) which brings about a supernatural disquiet, as if the film itself were haunted. But the summer goes on, and Eve and her family attempt to maintain the delicate balance of their lives.

Despite the looming darkness—the literal version of which is shot with a fantastical eye for the Gothic—Lemmons often strikes a light and funny tone. The family have a musical rhythm together. Louis is a charmer, his voice silky and smooth, a twinkle permanently in his eye. And he’s kind to Eve, Lemmons here highlighting a very human contradiction. How can a person be cruel and kind at once? And how much do our memories vilify or sanctify a person? Those are questions you only begin to form answers to in adulthood; Lemmons keeps us tied to Eve, her curiosity unable to yield anything but frustration. Hints that she may have the gift of her psychic aunt don’t help to make any more sense of the noise of childhood.

Similarly kind to Eve is her mother, Roz, and Roz’s psychic sister Mozelle (Debbi Morgan). Roz wants what is best for her children, and treats them with a degree of freedom, until she and her sister visit a roadside psychic who mentions her children, leading her to believe they are in danger. They’re housebound for the rest of the summer, a harsh decision made by someone desperate to hold on to what she has.

And that sense of desperation is felt so strongly in the time and in the setting. As childhood slips away and summer shuffles on, the lives that black Americans lead are also under existential threat in the film. It isn’t spoken about, nor is it depicted, but it’s felt. It’s there in knowing who their ancestors were, in understanding the violence of the time, and in the manner in which Lemmons presents their home. It’s beautiful but isolated. Surrounded by overgrown vines and willow trees, and ever-present shadows, in which seem to lurk everything and anything. This is a precarious situation: few black families in America, and fewer still in Louisiana, had much wealth in the 1960s. The Batiste family are fully aware of how much they have to lose, inside the home and out.

But Lemmons works wonders with what we don’t see. She’s masterful in how she handles the suggestions of threat and violence, and how she weaves together both the joyfulness of childhood and the melancholy that comes with the impossibility of it everlasting. And while so often films about black families focus heavily on explicit violence and black trauma— no doubt intended largely as learning tools for white audiences—Lemmons instead explores interiority, anxiety and longing. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than with Eve’s aunt Mozelle, a character of profound complexity that is written with the utmost care and compassion.

Eve spends much time with her aunt, learning about her stories and past marriages. Mozelle smokes and regales her niece with memories and wisdom, all of which seem so crushingly sad and beautiful that they’re alone enough to shape a young inquisitive mind. “There must be a divine point to it all that’s just over my head”, she tells Eve one night on a porch, cloaked in surrounding darkness but lit from the warmth of the house. “All I know is most people’s lives are a great disappointment to them, and no one leaves earth without feeling terrible pain”. She speaks with tiredness but not without some spark of kindness in her voice. As with her parents, and her older sister who told her what she’d seen was wrong, she is told this out of love.

Life is hard, and Eve is slowly learning this throughout that summer, as all kids do. Jurnee Smollett has a seemingly impossible task, in that she’s a preternaturally gifted actor playing a girl who is hearing and seeing the world as it is for the first time. She has premature wisdom clear in her eyes, yet has the ineffable quality that makes it seem as if this is a gift yet undiscovered. It’s a shockingly brilliant performance, precocious and innocent in equal measure. Lemmons carefully pushes the character along, taking a step towards adolescence as each scale falls from her eyes. She steals fruit after hilariously yelling at the vendor “too expensive!”, and begins concocting plans that involve voodoo to get back at her philandering father.

It’s funny because it’s filled with the desperation of being young, and the ensuing attempts at rebellion in increasingly absurd ways. Lemmons’ turns towards the melodramatic are refined and purposeful, tethered by down-to-earth humour. Both approaches are heightened in the manner that memories are. Thousands of moments are lost to time, but the ones that stick become legendary in the mind. Exaggeration gives them false memorability, and they play out in the film with the quality of a good anecdote. It is also, in its descriptive visuals and elegant dialogue, a truly novelistic film, one with the wisdom of the ages and a novel’s ability to transform the literal into the abstract.

The apparent ease of the film is actually the deft work of a director who possesses true clarity of vision, an artist working with absolute confidence and purpose, which gives the illusion of effortlessness. In reality, Eve’s Bayou is a deeply thoughtful work that finds space for a wealth of ideas. Childhood, womanhood, blackness, family, memory and guilt are just a few of the conversations the film strikes up, but never with abrupt literalness. Eve’s Bayou instead moves with a lightness that is almost ghostly, and which sets the film apart from its contemporaries.

While so many indie film directors were frantically stuffing every idea they had into their first films, Lemmons instead works with a sense of patience that allows her film to blossom as it progresses. And most importantly, it leaves it to the audience to decipher our own meanings. If Eve can’t decide on what she saw that night after the party, and a psychic has no answers as to how the world works, then Lemmons too knows that a director can’t tell us what we’ve seen and that a film’s power exists in its questions rather than its answers. Instead, the gift is ours: to take the tea leaves provided and read them ourselves. In doing that, perhaps we each form our own version of the truth.

USA | 1997 | 109 MINUTES (THEATRICAL ) • 115 MINUTES (DIRECTOR’S CUT) | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH

Criterion’s Blu-ray release of Eve’s Bayou celebrates the film as it deserves to be. It was shot on film by cinematographer Amy Vincent and this 4K restoration of the theatrical and director’s cuts are phenomenal. The texture and grain are kept, whilst the colours are vibrant and tasteful. Much of the film is set at night, and the darkness of the locations is deep and rich in these restorations. There are so many breathtaking compositions—not least the final shot of the film, of characters and their reflections in the water—and these painterly shots are done justice in this release. The 5.1 surround DTS-HD master audio soundtrack is also solid, though it does tend to push the score (one of the film’s few weak points) too high in the mix.

writer & director: Kasi Lemmons.

starring: Samuel L. Jackson, Lynn Whitfield, Debbi Morgan, Vondie Curtis-Hall, Brandford Marsalis, Lisa Nicole Carson, Meagan Good, Jurnee Smollett & Diahann Carroll.