BOOGIE NIGHTS (1997)

In 1970s California, a young man finds a new life and new friends as a porn star...

In 1970s California, a young man finds a new life and new friends as a porn star...

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Boogie Nights made his name as a writer-director and also repositioned teen heartthrob rapper Mark Wahlberg as a serious actor. In the memory of many, however, it’s probably neither Anderson’s screenplay and direction nor Wahlberg’s fine acting that stands out. More likely it’s the affectionately recreated time and setting (the 1970s-1980s California porn industry); perhaps also the performance of Burt Reynolds as Jack Horner, a maker of X-rated films who discovers Wahlberg’s Dirk Diggler and makes him a star; and certainly its famous final shot, in which the exceptionally well-endowed Diggler finally reveals his most prominent body part in all its prosthetic glory

Not showing us Diggler’s absurdly oversized penis has, to this point, been a running joke on the part of Anderson throughout Boogie Nights; it is, in a sense, the driver of the entire narrative and yet in a film jam-packed with sex and nudity it’s the one thing we haven’t been allowed to see. And certainly, having fun with the characters and the milieu seems to be a large part of Anderson’s agenda with Boogie Nights, which isn’t an out-and-out comedy but largely tongue-in-cheek, often slightly exaggerating people and events for the sake of absurdity before it suddenly and unexpectedly turns dark at around the two-hour mark.

Time hasn’t been wholly kind to the film. When I first saw it a quarter-century ago, I remember being delighted by the accuracy with which Boogie Nights recreated the 1970s in sets and props; it was the decade in which I’d grown up, but in 1997 it wasn’t yet distant enough to have become the object of mainstream nostalgia. Rewatching Anderson’s film 25 years later, however, those elements of the film—while still perfectly satisfactory—are far less beguiling, simply because we’ve now seen loving re-enactments of the era so often and done so well.

Indeed, one of the best recent renderings can be found in The Deuce, the HBO series created by David Simon (The Wire) and George Pelecanos, set in a similar world to Boogie Nights at much the same time. Slightly uneven in quality but at its best outstanding, The Deuce is emphatically not an hommage to Boogie Nights—it has major plot threads (such as Aids and organised crime) that Anderson barely touches on, for example, and a three-season series is of course far more complex than a single feature film—but there are clear resemblances, and perhaps something like The Deuce wouldn’t have been made if Boogie Nights hadn’t paved the way.

Before this film, after all, mainstream cinema portrayals of the porn industry had tended to the lurid and disapproving, typified by Paul Schrader’s Hardcore (1979)—a fine, grim-faced thriller on its own terms, certainly, but one that (completely unlike Boogie Nights and The Deuce) depicts pornographers as grotesque creeps and their world as a Taxi Driver-like circle of hell. Anderson didn’t change this overnight: if anything the world of porn as imagined by Joel Schumacher’s 8mm (1999) is even darker than that of Hardcore or Brian De Palma’s Body Double (1984). Nor is Boogie Nights entirely free of doom-and-gloom moralising itself. But its approach was strikingly fresh in 1997; and, given the worldview of big-budget movies often tends to the conservative, it may have been a belated reflection of more liberal attitudes toward porn itself that emerged in the ’70s.

Anderson’s second feature (after 1996’s Hard Eight, positively received but not a success), Boogie Nights was based on his half-hour amateur mockumentary The Dirk Diggler Story (1988), made when he was only a teenager, and that in turn was partly based on the life of the porn star John Holmes, who’d died around the time of its production. Elements of Holmes’s story survive into Boogie Nights, such as the abortive robbery sequence toward the end, and the idea of a series of adult films built around an action-thriller franchise, but it is not a biopic: Wahlberg’s character is much younger than Holmes, for example, and comes from a very different background.

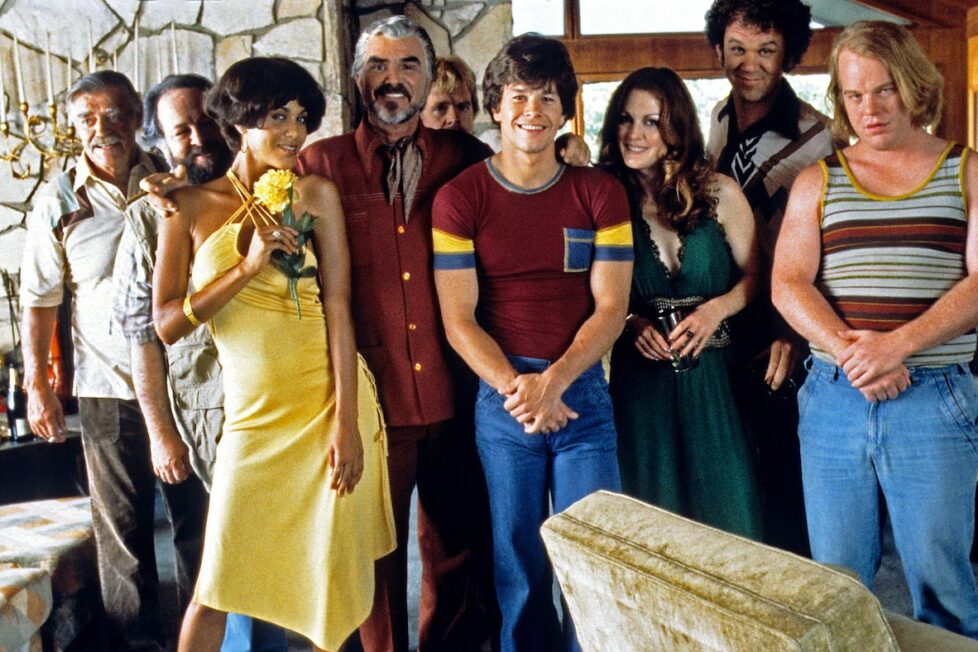

Boogie Nights starts in the San Fernando Valley, near Los Angeles, in 1977. The first characters we meet are the porn producer Horner (Reynolds) and star Amber (Julianne Moore), arriving at the Hot Traxx nightclub where Horner is soon distracted by the young busboy Eddie (Wahlberg) and goes to speak to him. “You want 5 or 10?” Eddie asks, then explains to an unfazed Horner that these are the prices he charges for a glimpse of his gargantuan and apparently widely coveted genitalia (“everybody’s blessed with one special thing”, Eddie says).

Horner, however, has more ambitious ideas: he wants to put Eddie in his films, and the boy (whose home life, with a bitter mother and ineffectual father, is horrible) is more than willing. In Horner’s entourage, he finds a new family and he turns out, too, to be a capable and professional performer in all the ways that matter for porn. Before long he’s a star, living in his own mansion with monogrammed drapes and a red Corvette parked in the garage. Eddie adopts the screen name Dirk Diggler and is successful enough to move into more upmarket X-rated productions, playing detective Brock Landers in a series of sub-sub-sub-French Connection films with random kung fu moments (footage from them provides some of Boogie Nights’ most hilarious moments).

As the 1970s turn into the 1980s, though, porn is changing with the shift from film to video—an evolution which here, as in The Deuce, is presented as a symbol of bigger transitions in society, the industry, and the way of life associated with it—and the atmosphere is changing too. Laid-back, dope-calmed attitudes morph into greedier, more aggressive mindsets fuelled by cocaine. This seems like it might become Dirk’s downfall, especially when it affects his ability to perform and after he meets another young man, Johnny Doe (Jonathan Quint), who has clearly been brought in by Horner to replace him.

Earlier hints in Boogie Nights of desperation and loneliness kept hidden beneath the apparent affability of Horner’s world—in particular, a subplot featuring Little Bill (William H. Macy) and his promiscuous wife—have seemed of marginal importance. But with Dirk’s fortunes falling as quickly as they had risen, the fond chucklesome mood of the film drains away very rapidly too, and as it follows him into increasingly dire straits, we have to wonder if this was always the truth that lay beneath and the happy veneer of earlier scenes was just that, or if the 1970s really were a Golden Age for Horner, Dirk, Amber, and their ragbag of colleagues.

Not that Anderson gives us much time to reflect while the movie is running. Individual scenes may often have a relaxed air but the structure of the narrative is frenetic, new developments constantly reshaping Dirk’s life and the relationships among other characters in the large cast; the camera restlessly prowls around Anderson’s busy movement-filled frames, matched by the energetic, varied music. Often the song lyrics directly reflect what’s happening on-screen, for example when Rick Springfield sings “she’s watchin’ him with those eyes” in “Jessie’s Girl” while Anderson holds the shot on Dirk’s eyes. But more abstract choices can work equally well. For instance, what sounds very like Wendy Carlos’s “Switched-On Bach” for a scene where Dirk practises boxing moves for the mirror (shades of Taxi Driver) or a montage to The Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows”.

As central as any of this to the impact of Boogie Nights, though, is the cast—many of whom (Moore, Macy, Philip Seymour Hoffman, John C. Reilly) became Anderson regulars. Macy, as the cuckolded Little Bill who makes his living from the commercialisation of sex but can’t cope with it in real life, is superbly comic and ultimately sad. Don Cheadle as the magnificently-named Buck Swope, with his ludicrous country-and-western attire and his ambitions to open a hi-fi shop, is another who is sad and sympathetic at the same time. Moore as Amber manages to be both maternal toward Wahlberg’s Dirk and a little in love with him. And there are many others in smaller roles who are hard to forget: Reilly’s Reed with his terrible poetry and his devotion to Dirk, Ricky Jay as the placid, bear-like Kurt, Joanna Gleason as Dirk’s frightening mother, Alfred Molina as the drugged-up motormouth Rahad.

More problematic to some viewers will be Hoffman’s portrayal of Scotty. The performance itself is masterful—witness for example the way that Scotty, gay and smitten by Dirk, manages to touch him just a little too often—but today it, and the way it’s written, could be seen as verging on the homophobic. Scotty is pathetic in his unrequited feelings, and the film goes out of its way at several points (starting with the girlie posters on his bedroom wall) to emphasise that Eddie/Dirk is not gay.

In any case, though, the two who tower above the rest of the cast—perhaps along with Moore and Macy—are Wahlberg and Reynolds. Wahlberg is funny but never less than convincing both as Eddie, the innocent abroad, and as the later, wasted Dirk; his ambitions and clumsy attempts at sophistication can be amusing (he literally imagines his name in lights, and speaks with awe of a “really famous design artist from Italy”) but they are touching too. Reynolds, meanwhile, has a difficult balancing act to achieve with the role of Horner, who must be both likeable and a little ruthless. He, and Anderson’s script, accomplish it by giving the character a vision that transcends exploitation. “How do you keep them [the audience] in the theatre after they’ve come?” he asks, before answering himself: “With beauty and with acting.” Because he believes—however foolishly—that he is doing something meaningful in making porn movies, the different aspects of his character, the opportunistic and the caring, combine to provide real depth while his euphemisms and cutesy phrases reinforce the idea that he’s less worldly than he initially seems.

Boogie Nights did well at the box office, was met with almost universal critical praise, and received three Academy Award nominations—although none of the nominees (Reynolds, Moore and Anderson for his screenplay) won. 25 years later, it doesn’t seem a perfect film: it probably doesn’t need to be so long, it can sometimes feel like the directionless Adventures of Dirk Diggler, and the comedic and more serious elements don’t always blend well.

Many will also consider that, in focusing on a man’s experience of the porn industry, it downplays the exploitation of women, and also point out that Diggler, Horner, and the rest are fundamentally nice guys; though Boogie Nights is almost certainly not intended as an apologia for porn any more than The Deuce was, it could be accused of skimming over more troubling aspects.

This isn’t wholly true. For example, it’s noticeable how much more aggressive Diggler’s replacement, Johnny Doe, is toward women, and a rape sequence late in the film provides its most disturbing passage. And Boogie Nights is certainly aware of the commodification of bodies, even if not specifically female ones: at the very end, when Diggler declares that “I am a star, I am a big bright shining star”, it’s not his face we see, but his penis. Still, it is a valid criticism that even if demonising porn producers in the style of Hardcore is overstating the case, Boogie Nights goes too far in the opposite direction for too much of its running time, and only occasionally allows a female perspective to compete with the boys’ club.

Despite these niggling thematic problems, though, for most audiences, any objections are likely to be ideological rather than visceral. Boogie Nights may not seem as groundbreaking as it did back in 1997, but it remains immensely engaging, and as good an example as any of Anderson’s skill in getting the very best out of his actors.

USA | 1997 | 155 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Paul Thomas Anderson.

starring: Mark Wahlberg, Julianne Moore, Burt Reynolds, Don Cheadle, John C. Reilly, William H. Macy & Philip Seymour Hoffman.