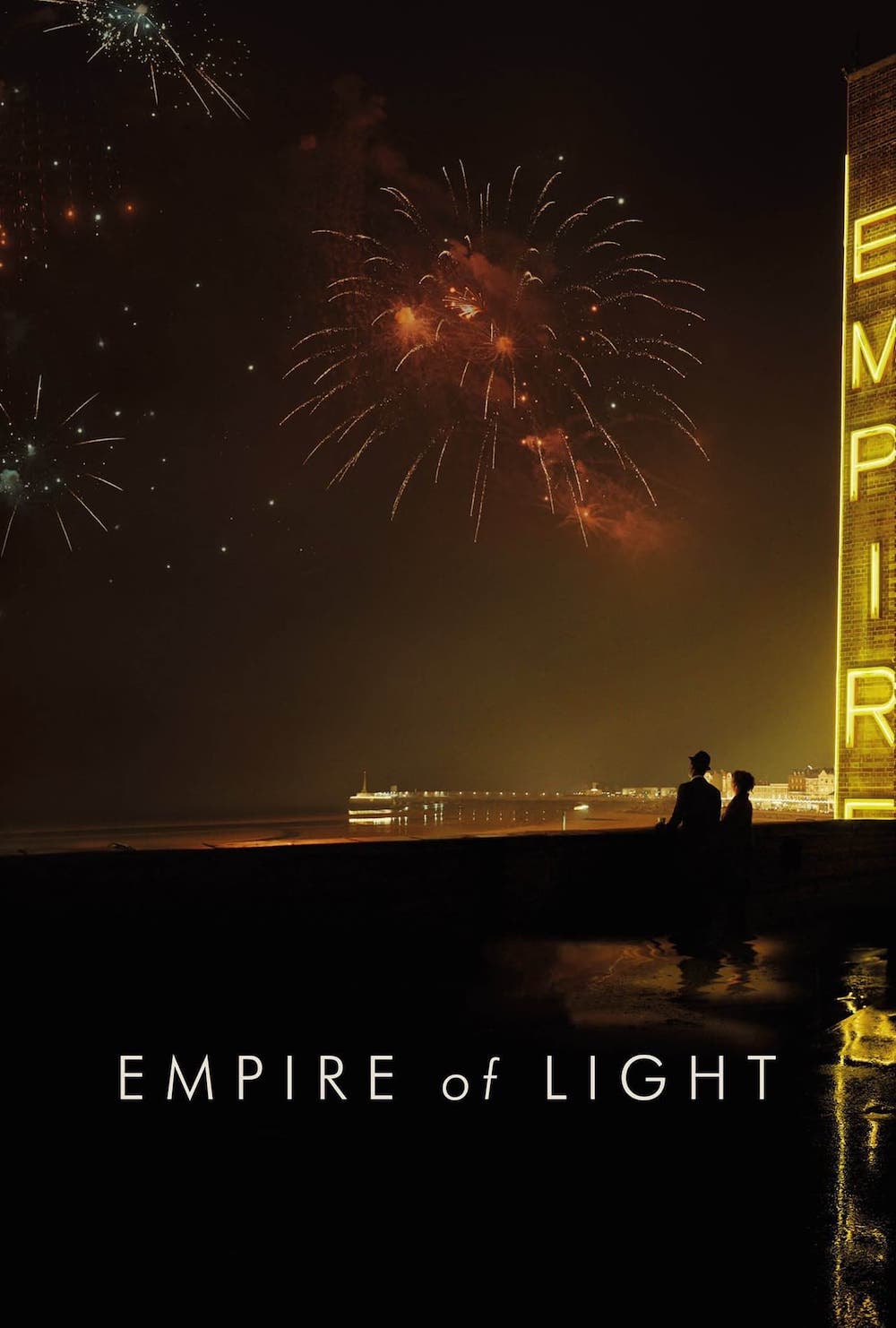

EMPIRE OF LIGHT (2022)

At a slowly decaying English seaside cinema in the early-1980s, a young black usher and older white manager fall in love...

At a slowly decaying English seaside cinema in the early-1980s, a young black usher and older white manager fall in love...

One of the better aspects of Sam Mendes’s Empire of Light is the way it handles the intergenerational romance between teenage, handsome, enthusiastic Stephen (Micheal Ward), and middle-aged Hilary (Olivia Colman), who’s verging on dowdiness and utter disappointment with her life.

In Mendes’s first film as a solo writer and director, he avoids all the usual sniggery older woman/younger man tropes, instead allowing the pair a fair bit of space for sweet and genuine human moments (including a rather Brief Encounter-ish scene in a café) and letting important developments, such as their first sexual encounter, be understood by allusion rather than literally shown. Even if a certain shallowness in characterisation means we can’t fully understand the depths of their relationship, it’s a strong and memorable element of the film.

Elsewhere, however, Mendes misses the mark in his handling of the many themes Empire of Light attempts to explore. For example, the racism directed at Stephen, a young black man, in early-1980s England is completely credible up to a point. In their different ways, an incident with a difficult customer (Ron Cook) at the cinema where Stephen and Hilary work and a frightening onslaught by National Front marchers, are equally powerful, perhaps the former even more so because of the way Hilary unwittingly tries to explain the customer’s prejudice away as mere bad temper. “He’s just an angry man, he’s always angry about something.”

But the film fails to convey how pervasive (although of course not universal) more watered-down forms of these hostile or derisive attitudes were in England at the time. For instance, it seems unlikely the entire cinema staff—including two middle-aged men, manager Donald (Colin Firth) and projectionist Norman (Toby Jones)—would be completely immune from the casual racism amidst which they must have grown up. Instead, it presents racial prejudice as existing only in extremes.

Similarly, while Hilary’s mental health is a key driver of the plot (she’s taking lithium, which her doctor extols as “marvellous stuff”—“I am not some problem to be solved”, she later protests), it too tends to come to the forefront only to provide an opportunity for histrionics. When she makes an ad-hoc, uninvited speech at a gala film premiere, her hair’s a mess and her dress isn’t done up properly. Soon after this, she has what can only be described as an old-fashioned “mad scene”, melodramatically half-lit with a looming huge shadow behind Colman. Hilary isn’t given much scope by Mendes to function normally and deal with her mental health issues at the same time.

The result is a movie which—rather like Mendes’s 1917 (2019)—might seem at first glance to be profound but, in the end, is rather flat and has little original to say but says it in an overdone, if visually arresting, way.

Empire of Light is set in a resort on the south coast of England in late 1980 and 1981 (the exterior of the cinema where much of it takes place is, in reality, the huge Dreamland in Margate, Kent, now closed but an important building in the history of cinema architecture when it opened in the 1930s). Hilary is the duty manager at the Empire Cinema, and Stephen’s a local boy who comes to work front-of-house after failing to get into university the first time around.

They fall in love, but Hilary’s shaky mental stability endangers both her job and their relationship. Meanwhile, the cinema manager is more or less forcing her into regular joyless sex in his office, Stephen’s old girlfriend Ruby (Crystal Clarke)—far closer to his own age—reappears on the scene, and plans are afoot for a gala regional premiere of Chariots of Fire (1981), while the National Front are on the streets. Nothing is quite tragic but nobody is quite content either; it’s very English in that regard.

It’s not strictly a character-led movie; one can’t shake the impression that many of the people in Empire of Light are there more to make a point that Mendes wanted to include, rather than being fully developed as individuals. Jones’s projectionist, for instance, has no real involvement in the storyline or much relationship with other characters, but his presence is necessary so that he can rhapsodise to Stephen about the magic of cinema (“viewing static images in rapid succession creates an illusion of motion.”)

At times this constrains the cast, though all are as excellent as the screenplay allows them to be. Colman, who’s given so many terrific performances recently (The Favourite, The Father) effectively melds fragility with strong-mindedness; her affection for Michael is as true-to-life as her occasional irritable outbursts.

Ward, a fine performer in Blue Story (2019) and also likely to be familiar to many from Netflix’s Top Boy, has a quietly assertive presence in his difficult role; it’s difficult because he’s presented as almost too perfect (he even tends to an injured bird) and because the combination of writing and casting make it easy to forget the character’s a relatively immature teenager rather than a man in his mid-twenties. He captures Stephen especially well in little details; stumbling and laughing at a roller disco, for example, while Hilary stays firmly on the sidelines and doesn’t even try to rollerskate.

The always watchable Jones is handed a slight stereotype in the part of the projectionist, but both his mild fussiness and his real passion are believable enough, while Firth is marvellously unpleasant as the pompous, selfish manager (condoms in his desk drawer, next to the Murray Mints). He should do more nasty roles!

Tom Brooke is amusing and plausible as another member of the cinema staff (even if it’s a failing of the film that all of them, the manager apart, are so likeable), while in smaller roles Clarke as Stephen’s ex and Tanya Moodie as his mother both stand out. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross contribute a score with piano to the fore which (exactly as with theirs for Bones and All last year) can be a tad trite at more romantic points, less so elsewhere.

There’s pleasingly observed detail in Empire of Light beyond the performances, too, from the Russell Hobbs Chelsea Teamaker at Hilary’s bedside to the tea dribbling from a Styrofoam cup down that irate customer’s front as he rages against Stephen for not letting him take a bag of chips into the movie—and, implicitly, for being an “immigrant”. As a former cinema worker, I can testify to the accuracy of the quotidian minutiae at the Empire, too. Like many provincial cinemas of the time it’s a little behind the cutting edge, playing The Blues Brothers (two months old) and All That Jazz (four months old) at the time Empire of Light opens, and that atmosphere of being somewhat past its prime is well conveyed.

Less convincing is Mendes’s obvious attempt to make Empire of Light a love letter to the art and experience of cinema itself, from the moment Hilary first turns the lights on in the lobby and Roger Deakins’s photography reveals its architectural splendour bathed in golden light, almost inviting us to worship it. Later, both Hilary and Stephen will coo over the now-shuttered cinema bar, a remnant of an age before the decay set in: “It really was beautiful,” she says, to which he replies “it still is”.

Stephen urges Hilary to actually watch movies herself as well as sell refreshments to customers, too, perhaps really imploring her to let herself dream and enjoy life; and indeed she ends Empire of Light as an audience of one for Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979), a film about a man finding happiness.

None of this fits happily, though, and it’s the least successful aspect of Empire of Light, feeling very much imposed by the writer-director rather than springing organically from the characters or their situations. And that, perhaps, encapsulates the movie’s fundamental problem: like 1917 it comes across as the kind of English film that’s straining for awards and a tone of literary seriousness by dressing up an essentially familiar storyline and half-realised characters in self-consciously poignant poetic trappings.

Despite sagging a little in the middle it’s completely watchable, but it’s also ultimately rather empty; static images in rapid succession do not, here, create an illusion of real people living real lives.

UK | 2022 | 115 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Sam Mendes.

starring: Olivia Colman, Micheal Ward, Colin Firth, Toby Jones & Tom Brooke.