THE LADYKILLERS (1955)

Five oddball criminals planning a bank robbery rent rooms on a cul-de-sac from an octogenarian widow under the pretext that they are classical musicians.

Five oddball criminals planning a bank robbery rent rooms on a cul-de-sac from an octogenarian widow under the pretext that they are classical musicians.

The Ladykillers, the last of Ealing Studios’ acclaimed comedies made before their complex was bought by the BBC and the brand absorbed into MGM British, has been restored and re-released by StudioCanal in cinemas and as a 4K Ultra HD Limited Edition Blu-ray set for its 65th anniversary. As Xan Brooks noted of director Alexander Mackendrick’s original film, it’s “as black as pitch and as corrosive as battery acid”, and contrary to the genteel British film as perceived by Joel Coen, when he and his brother were promoting their 2004 remake.

Mackendrick established his own style and approach within Ealing and brought his distinctive, subversive tone to five films: Whisky Galore! (1949), The Man in the White Suit (1951), Mandy (1952), The Maggie (1954) and, before he departed for America, The Ladykillers. He and fellow director Robert Hamer, who was responsible for Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), Ealing’s coruscating satire of upward mobility, were considered “downbeat” and “the most subversive and nonconformist directors” working there.

Mackendrick, born in Boston in September 1912, was the child of Glaswegians Frank and Martha, who had eloped to the US. At six years old, he was handed over to his grandparents after his father died in 1918’s influenza pandemic and his mother felt she couldn’t cope bringing up a child on her own. He returned with them to Glasgow in 1919 into what was “a lonely and fairly unhappy childhood.” However, while he lacked emotional security, the household was cultured and artistic and his intellectual curiosity was nurtured.

At Hillhead School, he was academically successful and particularly enjoyed drama and literature. However, his real talent was for drawing and his Aunt Janet encouraged him to attend art school after he left Hillhead at age 14. Between 1926 and 1929 he was enrolled at Glasgow School of Art where his perfectionism (a trait that dominated his approach to filmmaking and drove his Ealing colleagues mad) was duly noted in his dissatisfaction with everything he did.

When he began his search for work in London after leaving art school, it was his Aunt Margaret, a former secretary at the J. Walter Thompson advertising agency, who prompted his application to the company. He began at the bottom, pasting up layouts, but soon graduated to designer. He later considered this the perfect training for an aspiring filmmaker in that, a director, like a layout man, “leads the eye and ear of the audience.” Again, a Thompson colleague, Harold George, noted how indecisive he was and that “he was always changing his mind. It was going for perfection, I suppose.”

Working on commercials led to the development of his first film script, Midnight Menace (1937), co-written with his cousin Roger MacDougall and whose agent managed to sell the script to Associated British studios. Danny Green, appearing in the film as a heavy, was later cast by Mackendrick to play One-Round, one of the criminal gang in The Ladykillers. Within the agency, he also made inventive stop-motion animated Technicolor commercials for Horlicks with the legendary director-producer George Pal. At the outbreak of World War II, in partnership with MacDougall, he produced propaganda films for the Ministry of Information (one of them featured Alastair Sim, whom he wanted as Professor Marcus in The Ladykillers), and worked for the animation team of Halas and Batchelor.

As a US citizen, he was exempt from the war but co-opted by the joint Anglo-American Psychological Warfare Division to travel to Italy and work in the Leaflet Section, “to produce propaganda sheets to undermine the enemy morale.” He also co-produced short documentaries, one of which covered the aftermath of fascist atrocities committed in Rome after Mussolini was deposed and as the war drew to a close. Perhaps this gave him a certain detached perspective on the post-war period in Britain, that eventually filtered through into his work with Ealing and his cynicism about its ideals of collective unity versus bureaucracy.

He arrived at Ealing in 1946 after the collapse of Merlin Productions where, with his cousin Roger, he had made several documentaries for the MOI. He first worked as a scriptwriter and production designer on Ealing’s Technicolor production of Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948). Mackendrick’s first film as director in 1949, Whisky Galore, and scripted by Compton Mackenzie from his own novel, was something of an experiment after studio head Michael Balcon agreed to team Mackendrick with Ealing’s publicity-director-turned-producer Monja Danischewsky, whose original offer to director Ronald Neame to helm Whisky Galore had been turned down. The battle between the islanders of Todday and the officious Captain Waggett over the contraband whisky of the title became, under Mackendrick’s direction, a satirical, anti-bureaucratic one and a theme that would permeate many of his later films while “delivering comedy narratives that superficially conform” to the trademark Ealing formula.

After a period of working on second unit filming at Ealing, Mackendrick followed the unexpected success of Whisky Galore with The Man in the White Suit, a morally ambiguous exploration of trade unionism, capitalism, industrial unrest and scientific progress. Developed from a play by his cousin Roger, it was eventually scripted by him, Mackendrick and John Dighton. Dighton, who had co-written the screenplay for Kind Hearts and Coronets, added an edge to a script, one that gleefully picked apart the intertwined social and industrial mores of the film, that would eventually be nominated for an Academy Award.

After Mandy (1952) and The Maggie (1954), Mackendrick’s continuing relationship with Ealing was an unsettled one. He felt constrained, especially after his attempt to get two further projects off the ground, Mary Queen of Scots and A High Wind in Jamaica, had proved fruitless. His relationship with Michael Balcon was also uneasy after Balcon had ridiculed Mackendrick’s request to be made an associate producer at the studio. The studio was also beginning to atrophy, creatively and financially. The Ladykillers is “often seen as a meta-film, a commentary not only on England but also on Ealing’s own stagnation and refusal to move with the times.” The tensions Mackendrick felt, as he prepared his last film for the studio, not only about Ealing but also about a Britain that seemed hidebound by tradition, found their vehicle in the most unexpected of places.

Writer William Rose, an ex-pat like Mackendrick and fresh from the success of an Oscar nomination for the screenplay of Genevieve (1953), had had a “fruitful and turbulent” time working with Mackendrick on the script for The Maggie. So turbulent, in fact, that Rose had walked off the production. And there he was, when Mackendrick joined them, in the Red Lion pub on Ealing Green, regaling the studio’s fellow lunchtime drinkers with the details of a dream he’d had. Rose had woken up and then written down as much as he could remember of the dream. Five criminals, planning a robbery, live in a house with a sweet little old lady. She discovers their intentions and the criminals decide to kill her but end up killing each other. Rose’s dream runs like thread through The Ladykillers. As Reece Shearsmith notes in the documentary found on this release, the entire film appears like a hallucinatory nightmare, as a slightly off-kilter version of reality.

Although reluctant to work with Mackendrick again, Rose accompanied him to a meeting with Balcon who, once he had heard the idea, was left bewildered by their proposal: “Just let me get this straight. You have six principal actors and at the end of the picture five of them are dead. And you say this is a comedy?” For Mackendrick, it’s dark, nightmarish humour fitted the bill precisely and he found “the fact that it was something Bill had quite literally dreamed up really entranced me. Dreams are a marvellous source of imagery for movies.” Once a reluctant Balcon had given the film the green light and he and Rose had briefly buried the hatchet, Mackendrick chose editor Seth Holt, who shared his similar proclivity for dark humour and eccentricity, as his associate producer.

All three met regularly to construct the script, with Rose ad-libbing, adding his own sensibilities to the script, and then responding to Mackendrick’s and Holt’s improvisations and suggestions. During these sessions, Rose hit upon the idea of Professor Marcus and his gang pretending to be members of a string quintet using the old lady’s house for music practice. This, in turn, fired Mackendrick’s visual invention and, when Rose started to write the final screenplay, he was already in pre-production mode, designing and planning sets and scouting locations. There were certain parallels between the unhinged Professor Marcus and his creator, William Rose. Mackendrick recalled Rose was sensitive about discussing his mental health but, after Holt “jokingly told Bill that he was mad” it became the eventual undoing of the collaboration. An incensed Rose, despite Mackendrick’s attempts to calm the situation, abandoned the production when Holt refused to apologise. Holt and Mackendrick were then left to complete the screenplay, working from Rose’s rough notes. Rose later acknowledged that they had, in fact, improved upon his original ideas.

Mackendrick had hoped to cast Alastair Sim as Professor Marcus, the erstwhile mastermind in charge of his fellow train robbers, including posh con man Major Courtney (Cecil Parker), violent foreign gangster Louis (Herbert Lom), teddy boy hoodlum Harry (Peter Sellers) and the sentimentally dim but destructive One-Round (Danny Green), as they fetch up at the home of the seemingly genteel Mrs Wilberforce (Katie Johnson). As pointed out in the documentary on this release, the gang members could represent aspects of post-war, post Empire culture that troubled the conservative rigidity of the 1950s. Balcon vetoed Sim in favour of retaining Alec Guinness, a box office success with Ealing’s The Man in the White Suit, Kind Hearts and Coronets and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951). Guinness, upon seeing the script, was also convinced they should cast Sim but, given Balcon’s insistence, he took on the role and, sporting a set of bulging dentures, baggy eyes, and lank hair, turned in a nightmarish amalgam that referenced both Sim and critic Kenneth Tynan. Guinness refuted the latter was deliberate on his part.

Lom, then starring in the London run of The King and I, “had his own ideas” and was the perfect foil for Guinness, with Mackendrick using a sense of rivalry between both actors to underline the fractious relationship between the eccentric Marcus and the swarthy, violent Louis. Lom saw the film as something of a relief from his long run in the West End and Mackendrick creatively covered his shaved head to suggest an ignorant, thuggish interloper without the manners to remove his hat indoors. Parker had impressed Mackendrick in The Man in the White Suit and ex-boxer Green was also a familiar face to him.

Although Balcon considered Richard Attenborough for Harry, perhaps inspired by his turn as violent gang leader Pinkie Brown in Brighton Rock (1948), both Holt and Mackendrick held out for Peter Sellers as they were great fans of The Goon Show. Sellers considered The Ladykillers as “the first real film I made” and he observed Guinness like a hawk, wanting to learn from, and in awe of, someone he considered “my ideal… and my idol.” However, Sellers’ performance was trimmed during the editing of The Ladykillers and, with what he considered as one of his best moments, during the Major’s appeal to Mrs Wilberforce not to turn them in to the police, on the cutting room floor, he lost confidence in himself and the film. Mackendrick sympathised but, though Sellers was very funny, he ultimately felt the scene didn’t work in its entirety and cut it back. Indeed, the original script for the film was much longer and other scenes, shot by Mackendrick, were also dropped to maintain the film’s 90-minute running time. Lom and Sellers would, of course, be re-teamed later for several Pink Panther films.

Katie Johnson, then 77 and retired, was Mackendrick’s choice for Mrs Wilberforce but he could not persuade Holt she was capable of the role, who feared Johnson was too frail to withstand the rigors of being directed by Mackendrick. It was only after an alternate choice, one less older and “a little bit more robust”, died shortly after completing a screen test, that Mackendrick negotiated insurance for Johnson and secured Balcon’s agreement to her participation behind Holt’s back. Johnson even suggested she could pay for her own insurance because it was one of the best parts she’d ever been offered.

Filming took place in the summer of 1955 in the area of King’s Cross station and the art department used the now demolished Frederica Street, a cul-de-sac off the Caledonian Road that backed onto the railway lines in and out of the station, to build the exterior shell of Mrs Wilberforce’s slowly decaying house. A building conceived with no true right angles by Mackendrick and production designer Jim Morahan, it was complete with reinforced roof to facilitate the climax of the film. Some adjacent gasometers in Cheney Road provided spectacular vantage points above the area and Mackendrick was initially keen to set the heavy Technicolor camera up on the curved tops of the gasometers. Production manager David Peers recalled, “Sandy was one of those men for whom anything was possible. If he wanted it, he would get it, even if it meant killing half the crew. But he came round eventually and saw sense.” The set up deemed unsafe by Peers, Mackendrick reluctantly opted for a cherry picker and camera rostrum to get his high-angle shots.

To ensure the practicalities and details of the robbery were accurate, Mackendrick even consulted Scotland Yard and the Treasury. For the money used in the film, the latter gave “special dispensation for near-facsimiles to be used, on the condition that the props man kept them under lock and key, and counted them after each day’s shoot.” Scotland Yard also assured him, with a certain amount of concern, that the robbery itself “would work all too well.”

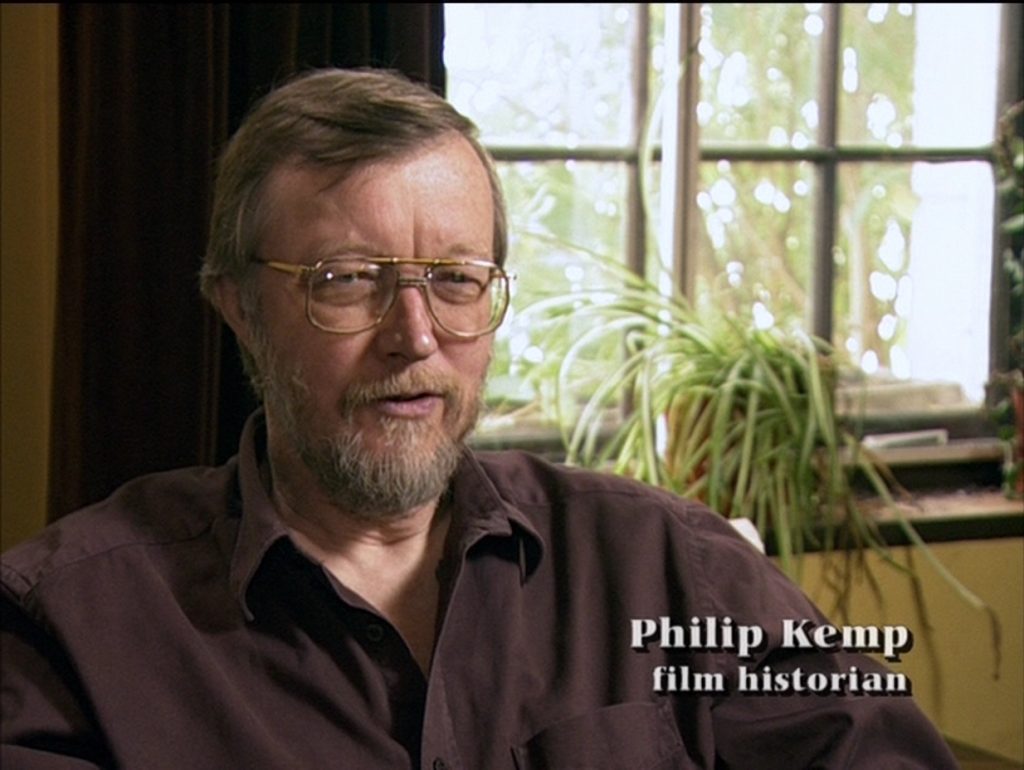

It is this attention to detail that fuels the dream-like structure of the completed film. The opening first act concerns itself with establishing a sense of place, introducing us to Mrs Wilberforce’s old house, Marcus’ gang and their plan to rob a train at King’s Cross station. Mrs Wilberforce appears immediately, an aged innocent trailing chaos in her wake and the Edwardian bulwark against the winds of change blowing through 1950s Britain, as she totters from her house to the local police station. She lives in a world in aspic, a relic of the said Edwardian age and serenaded in the opening sequence by a trilling music box arrangement of ‘The Last Rose of Summer’, redolent of, as Philip Kemp notes, “antique miniatures”.

That she, a forgetful old widow lost in a daydream, contains within her some supernatural force is first indicated in her approach to the baby in the pram outside the station. It’s immediate, youthful reaction is to bawl its head off at this bastion of old age. This is followed by her confession to the Superintendent that her friend Amelia’s report of flying saucers was nothing more than a dream, as is, in effect, the whole film that follows. Jack Warner, as the Superintendent, provides one of his variations on George Dixon, the constable he had played in Ealing’s The Blue Lamp (1950) who the BBC then resurrected for the long-running police series Dixon of Dock Green (1955–1976), the first episodes of which Warner was making during the filming of The Ladykillers. It was itself a series that ran out of time as more modern takes on the police drama usurped it in the 1970s.

Mackendrick emphasises his admiration for the Gothic and expressionistic touches of German cinema as the sinister figure of Professor Marcus, having discovered Mrs Wilberforce’s ‘to let’ ad in a local shop window, stalks around outside her house. This culminates in his unsettling introduction in silhouette at her front door before enquiring if she has rooms to let. We’re provided with an amusing topography of her lopsided Edwardian estate (indeed, One-Round later refers to her as “Mrs Lopsided”), her “very curious and charming house” settling into subsidence, walls, pictures, fittings and fixtures all askew. To appeal to her eventual and unwitting participation in his plans, Marcus explains his purpose for renting the rooms is so that his string quintet can practice. In essence, this means bunging on a record of the twee Boccherini minuet, music that effectively becomes Mrs Wilberforce’s signature tune (evoking her memories of a birthday party in Pangbourne where “someone came in and said the old queen had passed away”), to convince her that behind closed doors they are hard at work perfecting their craft when, in fact, Marcus and his gang are finalising their plans to rob a train.

Marcus’s plan to use Mrs Wilberforce in their robbery is greeted with resistance by some members of the gang, particularly the menacing Louis, but they agree to unwittingly deceive her into recovering the “lolly” from the heist. Thus, with her recruitment, follow the obstacles to their deception and the downfall of their scheme. All of the gang exist in a truly physical sense, their machinations often reduced to slapstick and farce in several beautifully timed and edited set pieces. This is in contrast to the still point of Mrs Wilberforce, who floats around as an unfazed observer. They are constantly interrupted, often by Mrs Wilberforce’s delivery of tea, which irritates Louis, who specifically foreshadows her transformation to come: “there’s just something about old ladies. I can’t… I can’t stand them.” When the quintet’s ‘practice’ is disturbed again by Mrs Wilberforce’s request to help give her parrot, General Gordon, his medicine, it turns into utter chaos and destruction after the bird bites Harry and escapes.

Their heist does go to plan and it is a wonderfully tense sequence that temporarily abandons farce for a grittier, more violent realism. However, Mrs Wilberforce causes mayhem, first by forgetting her umbrella, after collecting the money, stashed in a trunk, from the station in a taxi. Therefore, in having to return minutes later to the scene of the crime to retrieve it, she gives the anxious gang an experience akin to collective heart failure as they all squeeze into a telephone box to comprehend what’s going on.

This is followed by her reprimand of Frankie Howerd’s barrow boy, believing he is mistreating a junk man’s cart horse, where she then halts her taxi (driven by Carry On stalwart Kenneth Connor) and the delivery of the proceeds of the robbery. As she berates him, the barrow is upended, the cart horse trots off into the distance and, after an almighty punch up in the street, in the words of One-Round, she “puts all of them out of business in ten minutes.” The cart horse is reported missing at the police station as “a brown horse, eleven years old, and answers to the name of Dennis.” Abandoned by the taxi, the trunk carrying the money is eventually dropped off at her house by the police.

Yet, the gang fails to get away after One-Round’s cello case, stuffed with money, is caught inadvertently in the door as Mrs Wilberforce bids them farewell. This human factor, unforeseen by the slowly unravelling Marcus, exposes her to the proceeds of the robbery and effectively traps them in the house. There they are outnumbered and emasculated by a geriatric gang of Mrs Wilberforces, as her friends descend en masse for tea, a melancholic singalong and with newspaper headlines brandished by Ealing regular Edie Martin that allow her to put two and two together. At this point, the film becomes a darker, amoral odyssey as they try and convince the “shocked and appalled” Mrs Wilberforce that, at first, the money is insured and is no great loss to the bank, or then to let them go by appealing to her better nature with sob stories about the Major’s mother. When she refuses to accept any of this and stands up to them about this “most embarrassing position”, they blackmail her as an accessory not only to this crime, because she “carried the lolly”, but to also take the fall for “the Eastcastle Street job.” Finally, in desperation, they plot to kill her. What could go wrong?

The final act is by far the bleakest expression of Mackendrick and Rose’s contemplation of what they could see happening in Britain as the forces of modernity, nonetheless criminal and corrupt in the film, meet the implacably and deceptively calm eye of a pre-war hurricane, where morals and standards are upheld in a stultifying, dusty old house sitting atop the unforgiving, industrial nightmare, all screeching trains, acrid smoke and murderous signals, of the King’s Cross railway lines. The gang’s resolve is abandoned when, after drawing lots to bump off Mrs Wilberforce, they turn their frustrations inward. As she nods off in her armchair, the Major falls to his death, attempting to abscond with the money, and is deposited by wheelbarrow onto the rails under the Caledonia rail tunnel, and One-Round kills Harry after he sees Mrs Wilberforce asleep and believes he has murdered ‘mum’, as he refers to her, the mother to be “killed for rather than be killed.” Louis disposes of One-Round and he and Marcus are left to fight it out high above the railway lines.

It’s a dark, pessimistic ending that reinforces the view that Mrs Wilberforce’s Gothic house represents “the past that never really goes away”, a British past that emerges time and again to “defeat this unseemly modern mob.” While Mrs Wilberforce dreamily drifts through the film, this nascent British modernism fractures and the squabbling factions do themselves in. When Marcus, descending into madness, declares that “no really good plan could include a Mrs Wilberforce” and accepts that his gang has been thwarted by a past that is never past, Charles Barr underlines Mackendrick’s view that “their downfall is a simile for England’s inability to ever become fully modern.” Yet, perhaps, it was all a dream conjured up by Mrs Wilberforce’s own imagination. The police seem to think so and, by inadvertently doing the right thing, she totters away with the lolly and returns to a home which, for Mackendrick, is a lopsided Ealing, now even without a studio base of its own, that he is compelled to leave behind for America. As a parting salute, The Ladykillers is sublime.

UK | 1955 | 91 MINUTES | 1.37:1 • 1.66:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

The film really benefits from its 4K restoration, ramping up the detail in faces and clothes, amplifying Otto Heller’s luminous Technicolor symbolism in its contrast between exteriors and interiors and the characters occupying them. The darkness at the heart of the film is also made especially present in the inky shadows of this 2020 upgrade. What’s also worth noting is the soundtrack, showcasing composer Tristram Cary’s inventive mix of music and sound effects, that gives the film a palpable rhythm and pulse, punctuating his score with mallets banging old water pipes into life and the banshee cries of trains passing in the night.

You also have two screening ratios for the film: its original uncropped 1.37:1 or Academy ratio, and a slightly matted 1.66:1 widescreen equivalent that reflects the transitional period for widescreen presentation in cinemas during this period. It’s sensitively done as the 1.37:1 does appear to have been shot with the required clearance at the top and bottom of frame to facilitate widescreen projection at 1.66:1 at the time. Overall, both ratios provide a handsome presentation.

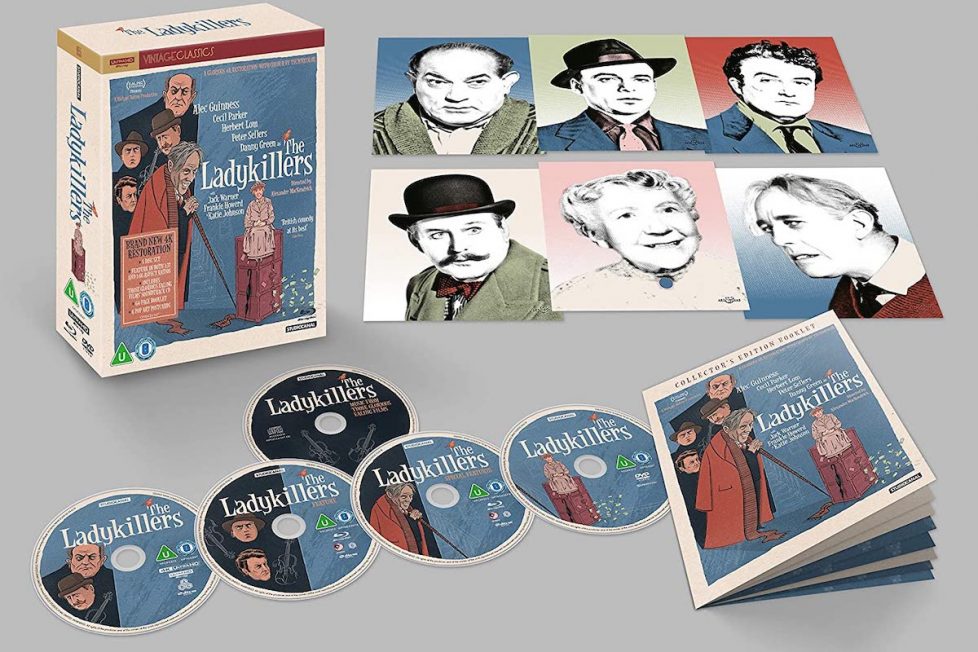

The Blu-ray releases of 2015 and 2010 originally included an introduction by Terry Gilliam, more extensive interviews with screenwriter Allan Scott, Mackendrick’s former film school pupil director Terence Davies and friend, writer Ronald Harwood, plus a feature on the restoration undertaken for the original Blu-ray release. The introduction and restoration featurette are not included on this new 4K disc. However, StudioCanal’s new release does contain the rest of the original extra features as well as new documentaries, a soundtrack CD, booklet, and art cards. Worth the upgrade!

director: Alexander Mackendrick.

writer: William Rose.

starring: Alec Guinness, Cecil Parker, Herbert Lom, Peter Sellers, Danny Green, Jack Warner, Frankie Howerd & Katie Johnson.

I am indebted to the following sources: Philip Kemp, Lethal Innocence: The Cinema of Alexander Mackendrick (Methuen, 1991) • Charles Barr, Ealing Studios (Cameron and Hollis, 1998) • Mark Duiguid, Lee Freeman, Keith Johnston and Melanie Williams (eds), Ealing Revisited (BFI, 2012) • Robert Sellers, The Secret Life of Ealing Studios (Aurum, 2015) • Roger Rawlings, Ripping England!: Postwar British Satire from Ealing to the Goons (SUNY Press, 2017) • Roger Lewis, The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (Random House, 1995) • Andrew Horton, Joanna E. Rapf (eds), A Companion to Film Comedy (John Wiley & Sons, 2012) • Jeffery Richards, Films and British National Identity: From Dickens to Dad’s Army (Manchester University Press, 1997) • Xan Brooks, ‘The Ladykillers: No 5 best comedy film of all time’, The Guardian (18 October 2010).