THE MAURITANIAN (2021)

An American lawyer takes on the case of a suspected al-Qaida terrorist detained at Guantanamo Bay without trial.

An American lawyer takes on the case of a suspected al-Qaida terrorist detained at Guantanamo Bay without trial.

Three years ago, Tahar Rahim reminded us what a subtle and intriguing actor he is when starring alongside Jeff Daniels in Hulu’s 9/11 miniseries The Looming Tower. There he played a Muslim agent on an FBI counterterrorist squad, but in Kevin Macdonald’s interesting but predictable The Mauritanian he switches to the other side of the interrogation table, playing Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a Mauritanian man incarcerated by the US military at Guantánamo Bay between 2002 to 2016.

Slahi was suspected of involvement in the 9/11 hijackings on the basis of a brief affiliation with al-Qaida dating back to the early-1990s, when Osama bin Laden’s organisation was fighting Communists in Afghanistan as a partner, rather than an enemy, of the Americans. He had had other, apparently minor and tangential connections with al-Qaida later on, too. But he was never charged with any offence, and when his case finally came to court the judge ruled that the government had not shown he was still a member of al-Qaida in any meaningful way by the time of the 2001 terror attack.

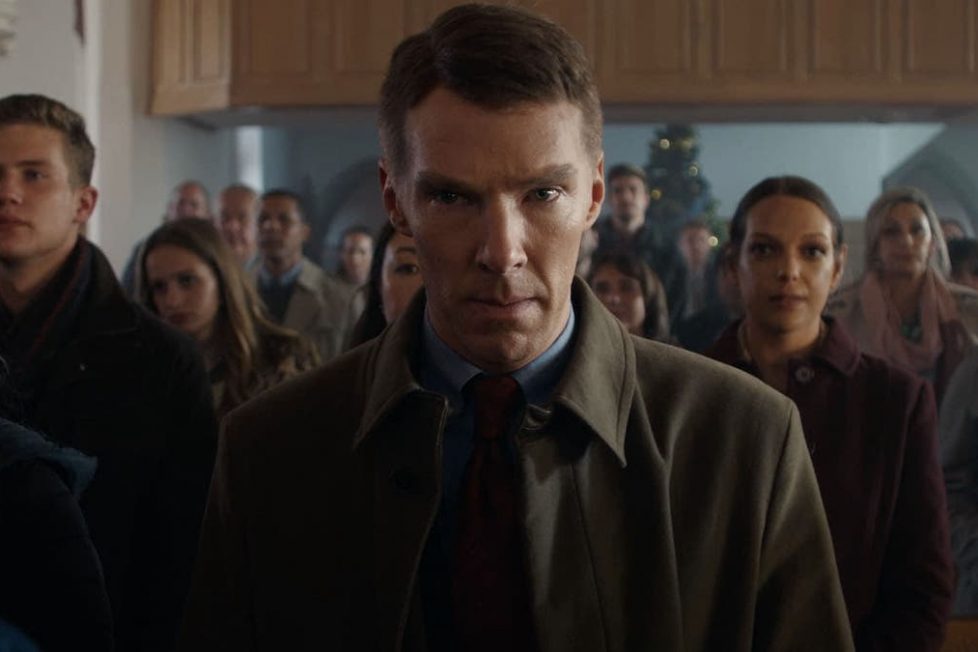

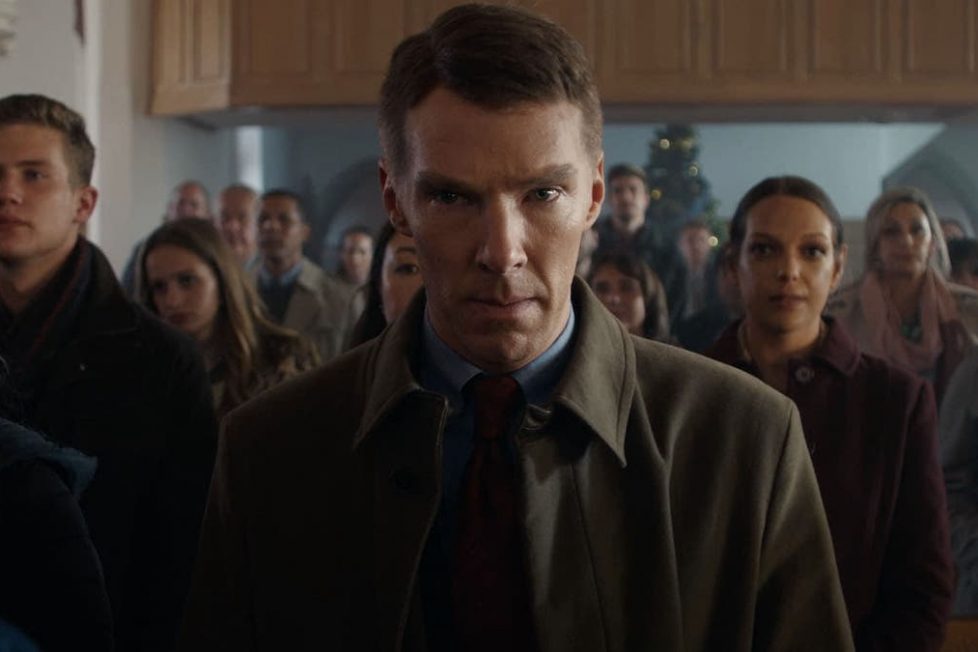

The Mauritanian follows Slahi from his capture by the Americans to that case in 2010 (which, although it appeared to go in his favour, did not free him immediately, as the government appealed and the fight dragged on). And it’s underpinned by outstanding performances from three actors who not only play real people in this saga, but also represent different perspectives on the post-9/11 period. Rahim is the seemingly victimised Muslim, Jodie Foster plays his defence attorney Nancy Hollander stands in for western liberal sentiment, and Benedict Cumberbatch appears as Stuart Couch, the Marine Corps lawyer leading the prosecution, who’s initially the embodiment of America’s thirst for revenge.

It takes a more or less chronological route through the tale, beginning with an unwitting Slahi being taken away from a wedding party in Mauritania. His mother (Baya Belal) wonders if it’s about an unauthorised satellite dish he’s recently erected, and he seems confident there’s no problem, telling her to “save me some tagine”. But we can tell he’s worried when he erases all the contacts on his phone.

We might briefly wonder, too, if this is to protect the innocent or disguise the guilty. However, as the film jumps forward a few years to 2005 and Foster’s Hollander takes on his case (despite her law firm’s misgivings over appearing to defend a terrorist), it becomes increasingly clear this is going to be an outsiders-against-the-establishment story.

Hollander is soon at Guantánamo meeting with Slahi for the first time, and her trip to the camp is one of several sequences soaked in an unsettling atmosphere of unspoken menace. She has her own brief doubts over the revelation he once received a call from bin Laden’s satellite phone, and she shifts the emphasis of her case away from Slahi’s innocence to the (il)legality of his incarceration. Still, the stumbles in their mutual trust are brief.

Cumberbatch’s Couch, meanwhile, is gung-ho and looking for the death penalty. He has a personal interest in the case (a friend was a pilot on the plane that hit the South Tower of the World Trade Center), but he and his team are also convinced the government has the right man. “This dude is the al-Qaida Forrest Gump,” one of them says of Slahi. “Everywhere you look, he’s there.”

Couch is not, however, one of those who believed that after 9/11 the end would justify the means. He’s absolutely upright, as committed to the rule of law as he is to his country, and he starts to grow puzzled and frustrated when the US government (more concerned about protecting the secrets of Guantánamo than giving its prosecutor the tools to do his job) refuses to hand over information about Slahi’s interrogations. Eventually he too is having doubts about his cause. Someone has to answer for 9/11, he observes, but “not just anyone.”

You can see where this is heading, and the problem with The Mauritanian is precisely that. It may seem unreasonable to object to a film with an unimaginative narrative arc when it is based on a true story (The Mauritanian goes so far as to embolden the word “true” in the opening title making this declaration). After all, if that’s what happened, that’s what happened!

But it would’ve been a more challenging and provocative movie if the filmmakers had selected a story that didn’t develop in such an obvious direction, or if at least one of the leads had been genuinely unlikeable. As it stands, the main character’s drama (as opposed to the grim experiences of Slahi at the hands of his barely-characterised jailers) is focused almost constantly on displays of human decency and civilised values, and the result is a film where the mood is surprisingly upbeat—despite the dire straits of the man at its centre.

Having said that, shameful as the Guantánamo episode was, maybe a wrenching exposé is not the only film to be made about it. Movies from Michael Winterbottom’s semi-dramatised documentary The Road to Guantánamo (2006) to Scott Z. Burns’s The Report (2019) have looked at the injustices; and The Mauritanian does work—just in a very different way, that’s more Shawshank Redemption (1994) than Midnight Express (1978)—as a personal story about endurance, determination, friendship, and contentment found in the least expected places.

In large part this is down to the three leads. Foster’s terrific as Hollander, capturing (as she did in 2018’s Hotel Artemis) a woman who’s now much closer to old age than youth. One can imagine a full life behind her, where setbacks have only hardened her resolve, now expressed in the super-efficient attitude and the thin, clipped smile that keep her undoubted anger and passion for justice under control.

Cumberbatch also makes for a convincing American military man. His Couch is reliable, straight as a die (you can hardly believe it’s the same actor who gave us such an eccentric and unpredictable Dominic Cummings in 2019’s Brexit: The Civil War) but not lacking at all in intelligence or humour. Marine lawyers “like to fully consider a problem before we blow it up”, he tells Hollander.

In many ways, Couch is the more interesting of the pair because his position, unlike the resolute Hollander’s, does change over the course of the film. And if they originally seemed like opposites, by the end The Mauritanian is overtly drawing parallels between them—like, for example, a cut from Couch receiving government documents to Hollander receiving a letter from Slahi.

But both of these performances, fine as they are, will probably fade in the memory while Rahim’s superb Slahi lasts. Always a powerful actor, from Jacques Audiard’s The Prophet (2009) to the BBC-Netflix series The Serpent (2021), Rahim has the luxury of many scenes on his own and many more where the only other characters present are minor ones. These give him space to develop Slahi into a completely credible person, distressed by his incarceration but also easily capable of happiness despite the adverse circumstances, for example in the companionship he finds with a French prisoner he can speak to only through a fence.

Slahi is confused, he’s frightened, but then he’ll break out into a grin, or take a delight in the phrase “see you later alligator” (he’s been learning English). Little touches abound to quietly show how he’s being changed by his imprisonment: the compliance with which he starts to obey guards’ orders before they’ve even been given, the way that the McDonald’s he at first sniffily declines he will later accept hungrily.

Importantly, too, once the relatively benign regime of his earlier days at Guantánamo—books, exercise, reasonable treatment—has been replaced by the horror of the “special measures”, Rahim doesn’t overdo the effect on his character. He remains recognisably the same man, just more broken.

Elsewhere in the cast, Shailene Woodley engages the interest in the role of a younger lawyer assisting Hollander, in principle as committed as her superior but less emotionally secure, and unnerved when she realises that she might end up arguing on behalf of a real terrorist. Zachary Levi, Robert Hobbs, and Bill Seidel are also effective as members of the US military who are, to a greater or lesser extent, pitted against Slahi, Hollander and Couch.

In its visual style, The Mauritanian does little to distract from the performances, largely maintaining a quasi-documentary style suggesting the camera is in real spaces—especially Slahi’s tiny cell. The framing can feel haphazard even when it’s actually conventional, obstructions are often allowed to remain in view. (Director Macdonald’s filmography includes two exceptionally fine documentaries that were among the best of their era, 1999’s One Day in September and 2003’s Touching the Void, as well as a number of drama and thriller features.)

Flashbacks to Slahi’s past in Afghanistan, Germany, and the Mauritania of his childhood detract from this fly-on-the-wall impression a little, as does Tom Hodge’s slightly sentimental score, especially in the climactic courtroom scene. But the stylisation of the torture sequences—hallucinatory glimpses through strobe lighting—is a potent way to convey their nightmare quality without lingering on them voyeuristically. (The calm, detached medical language of the official reports is even ghastlier, though.)

The Mauritanian does suffer from the way the core three individuals are, if not quite flawless, all unusually good people. Not only does this minimise any conflicts among them, it’s also hard to believe that they won’t overcome the obstacles set between them and justice; with such Hollywood characters we expect a Hollywood ending (which adds some irony to the closing title revealing how much longer Slahi’s imprisonment dragged on). The movie can be just a little too slick, as well, again working against the rawness that you might think its subject matter calls for.

However, if you can accept this, and think of it primarily as a “Slahi movie” and secondarily as a “Hollander and Couch” movie (rather than as a “Guantánamo movie”), there’s much to draw you in and keep you transfixed. And, of course, thinking of it that way also means thinking of it as a Rahim, Foster and Cumberbatch movie, something entirely merited by their near-perfect performances.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider buying me a coffee.

UK • USA | 2021 | 129 MINUTES | 2.35:1 • 1.33:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • FRENCH • ARABIC

director: Kevin Macdonald.

writers: M.B. Traven, Rory Haines & Sohrab Noshirvani (based on ‘Guantanamo Diary’ by Mohamedou Ould Slahi).

starring: Jodie Foster, Tahar Rahim, Benedict Cumberbatch & Shailene Woodley.