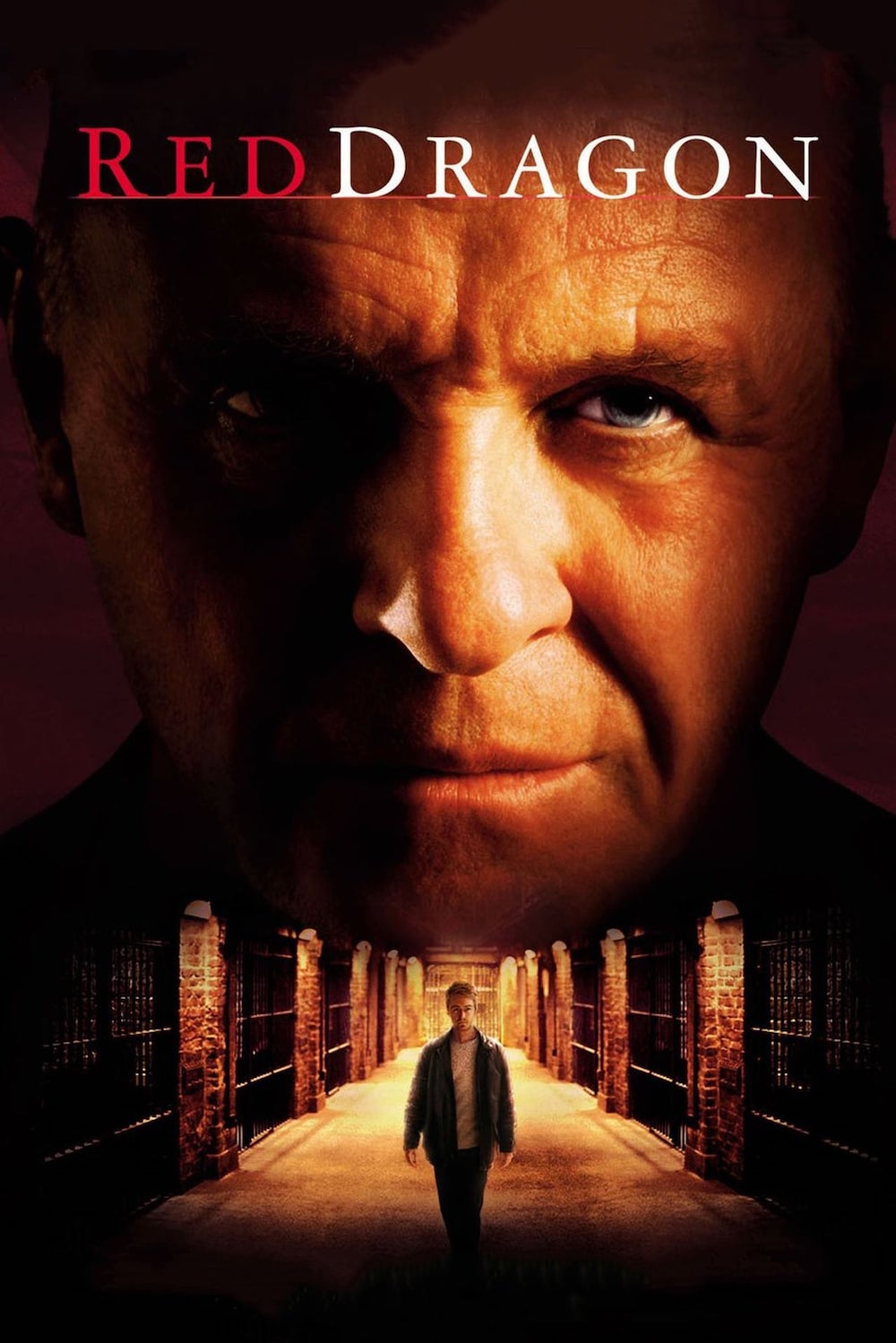

RED DRAGON (2002)

Baffled by the case of a ritualistic serial killer, an FBI agent seeks advice from Dr Hannibal Lecter...

Baffled by the case of a ritualistic serial killer, an FBI agent seeks advice from Dr Hannibal Lecter...

The fourth of the five Hannibal Lecter movies was obliged to be many things at once. Red Dragon is strictly speaking an adaptation of Thomas Harris’s 1981 novel (the first featuring the character), but to most people, it was foremost a prequel to both The Silence of the Lambs (1991)—a hugely influential film which popularised psychological profiling in crime fiction—and its own hit sequel Hannibal (2001).

Meanwhile, to serial killer buffs if not general audiences, Red Dragon was also a remake of Michael Mann’s Manhunter (1986), based on the same novel. It had made few waves on its release, but by 2002 it was becoming better-known to audiences who couldn’t get enough of serial killer psychology in general or Lecter in particular (whose screen debut it was).

Brett Ratner, while relatively new to the director’s chair, had already scored two major commercial successes with Rush Hour (1998) and Rush Hour 2 (2001), and Red Dragon pushes his total box office sales close to the billion-dollar mark. Screenwriter Ted Tally, meanwhile, was a less hot property by the beginning of the new century because his last three movies had all been poorly received, but as the Academy Award-winning writer of The Silence of the Lambs he was an obvious choice for Red Dragon, and indeed had turned down the chance to write Hannibal in favour of this project. His screenplay is closer to Harris’s novel than Mann’s screenplay for Manhunter was, though neither differs greatly.

So it’s little surprise that Red Dragon is at heart a cautious and conservative film much closer to Silence and Hannibal than to Manhunter. It’s happy to treat us to graphic and grotesque (if brief) images of mutilated bodies (although only one actual killing is seen in the film), but nervous about allowing the killer played by Ralph Fiennes to become too human in the audience’s eyes, and reluctant to spend too much time underlining the similarities between him and Edward Norton’s FBI agent, both respects in which Mann’s earlier adaptation excels.

Visually, too, it’s more similar to Silence and Hannibal—shot in an essentially conventional Hollywood crime-thriller style with appropriate touches of horror idiom, certainly not above some melodramatic photography and lighting but far from Mann’s intensely mannered visuals—and the prolific Danny Elfman’s score, while suspenseful and original in some passages, resorts to banality at others.

Nor is it any surprise, given commercial expectations, that the character of Lecter (Anthony Hopkins) plays a far larger role in Red Dragon than his importance to the story warrants. Indeed, the movie opens with an almost black-humorous scene of the murderous psychiatrist at a symphony concert in Baltimore in 1980, before his arrest. The conductor of the orchestra is the film composer Lalo Schifrin, but Lecter’s eye is on a portly flautist.

We can guess from that half-amused, half-animal expression which Hopkins uses so often for Lecter that his interest isn’t musical, and our suspicions are confirmed soon after at a dinner he hosts for the orchestra’s board, at which a missing musician is mentioned. “Hannibal, confess—what is this divine-looking amuse-bouche?” asks one of his guests, and nobody who’s seen Silence or Hannibal needs to be told.

The 1980-set prelude continues with a visit to Lecter (who unexpectedly sports a short ponytail) by Will Graham (Edward Norton), an FBI agent who’s been consulting him in the hunt for a cannibalistic serial killer. Again, the audience is surely presumed to realise that Lecter himself is the unidentified murderer they’re discussing. “How I’d love to get you on my couch,” Lecter tells Graham, and one suspects his intentions aren’t wholly therapeutic. But during their conversation, Graham realises the truth—it’s an annotation in Lecter’s copy of Larousse Gastronomique, the haute cuisine bible, which finally makes the penny drop—and Lecter is apprehended, though not without seriously wounding the agent.

This, of course, provides the background not just for Red Dragon itself but also for both The Silence of the Lambs and Hannibal, which feature Lecter first incarcerated and then escaping. (The final Lecter movie, 2007’s Hannibal Rising, goes further back to his youth.) The bulk of Red Dragon, though, is set several years later, long after Lecter’s apprehension but before Silence.

It starts with a senior FBI agent, Jack Crawford (Harvey Keitel), visiting the now-retired (but still young) Graham at his home in Florida, where Crawford tries to persuade Graham to come back to law enforcement and help with the effort to apprehend a serial killer known as the Tooth Fairy.

Following genre convention, Graham’s initially reluctant but then accepts and is soon walking around the home of a slaughtered family, recording his thoughts—several scenes like this in Red Dragon are highly reminiscent of Manhunter, even if the more naturalistic cinematography isn’t, despite Dante Spinotti serving as director of photography on both films.

Graham also visits Lecter in his apparently subterranean cell; here the blue-grey palette is very much like Manhunter’s, and Lecter’s early comment on Graham’s aftershave is surely a knowing wink back at his comments on the perfume worn by Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) in Silence of the Lambs.

As in Manhunter, the identity of the perpetrator is revealed quite early on, about 40-minutes into the movie. He’s Francis Dolarhyde (Fiennes), a young man badly abused as a child who now works at a video-processing lab (guessed how he picks his victims yet?). The precise nature of his delusions is never quite clear, but he seems to be obsessed with a William Blake painting of the “Great Red Dragon” from the Book of Revelation (an artwork he later eats, in one of the movie’s more extravagantly OTT moments), and to believe his murders are transforming him into this all-powerful creature.

In more grounded periods, Dolarhyde also forms a tentative relationship with a blind co-worker, Reba (Emily Watson). As in Manhunter, this is the most humanly interesting facet of the storyline, far more than Graham’s relationship with Lecter (gripping though some of their exchanges are) and certainly more than the clichéd final threat to the investigator’s own family. Meanwhile, a further subplot is provided by the antics of tabloid journalist Freddy Lounds (Philip Seymour Hoffman), whose lurid reporting on the case manages to make enemies of both the FBI and Dolarhyde.

With so much going on and at least three main characters of equal importance—Graham, Dolarhyde and Reba—Red Dragon moves almost too fast at times, especially around its midpoint. But for the most part, its complexities are well-managed by Ratner and Tally, the logic taking the story from one step to the next is always understandable, the characters’ different levels of knowledge are clear, and motivations are never implausible.

A few scenes are especially impactful— Graham talking to Lecter, for example, or an FBI team listening to a recording of a victim’s death—although aficionados of Manhunter will be disappointed that less is made of Dolarhyde and Reba’s visit to a zoo. But Red Dragon is largely a film that succeeds not so much through individual scenes as through its interlocking storylines, where the next developments are rarely obvious even if the ultimate outcome is, and through its strong ensemble cast.

Red Dragon’s characters are familiar types rather than original creations, but the actors mostly invest them with real depth. Norton, in particular, convinces with his quiet assurance, finely-graded expressions and small gestures: at one point, realising that he’s sitting in the same chair as a dog seen in a home video made by a murdered family, he glances down at the chair just long enough to signal it to the audience.

He’s probably too young for the part (only a little over 30 when the film was made and yet is supposed to have been a relatively experienced FBI agent who then retired for several years before events take place) and that realisation does intrude occasionally, but not enough to seriously harm his credibility.

Strong performances come also from Fiennes—a little more scenery-chewing than Tom Noonan playing the same role in Manhunter but equally capable of eliciting both sympathy and fear and making us believe the mild-mannered “normal” Dolarhyde and the ferocious, ecstatic Red Dragon are the same man—and from Watson, who doesn’t overplay Reba’s vulnerability (or her blindness) and lets us see both her emotional devastation and her inner strength in a nice final scene with Graham.

Anthony Heald is memorable as the smug, vain, ambitious, incompetent psychiatrist who heads the institution where Lecter is held—Lecter says he “fumbles at your head like a freshman pulling at a panty girdle”—and Hoffman does a seedy, slightly stupid, amoral hack as only Hoffman could.

For many, of course, Hopkins as Lecter will be the obvious “star”, but it’s difficult to say he does much more here than reprise his Silence role (with an occasionally questionable accent), and probably wasn’t asked to add much to the character. Unquestionably, many aspects of Lecter in Red Dragon—the reappearance of his outlandish mask, the diabolical facial expression at the end—seem to be present purely to satisfy audience expectations.

Despite this, Red Dragon couldn’t match Silence of the Lambs or Hannibal in box office terms—the latter remains the most successful Lecter film in terms of revenue, though Silence with its smaller budget delivered a far greater return on studio investment. But it performed healthily (and much better than Hannibal Rising, the last of the post-Manhunter quartet of Lecter films and the least successful both critically and commercially).

Critically, it was neither acclaimed nor panned, rightly recognised as a well-crafted movie but one that trod little new ground. And indeed, ultimately—despite Harris’s reputation, Ratner’s golden directorial touch, and Lecter’s towering pop-culture status—it is to some extent just another serial killer flick.

But in a genre where so many productions are so derivative or simply bad, Red Dragon (like the rest of the Harris/Lecter films) is an impeccably executed potboiler, and if it’s only superficially thoughtful, even that sets it head and shoulders above most of the rest.

USA | 2002 | 124 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Brett Ratner.

writer: Ted Tally (based on the novel by Thomas Harris).

starring: Anthony Hopkins, Edward Norton, Ralph Fiennes, Harvey Keitel, Emily Watson & Philip Seymour Hoffman.