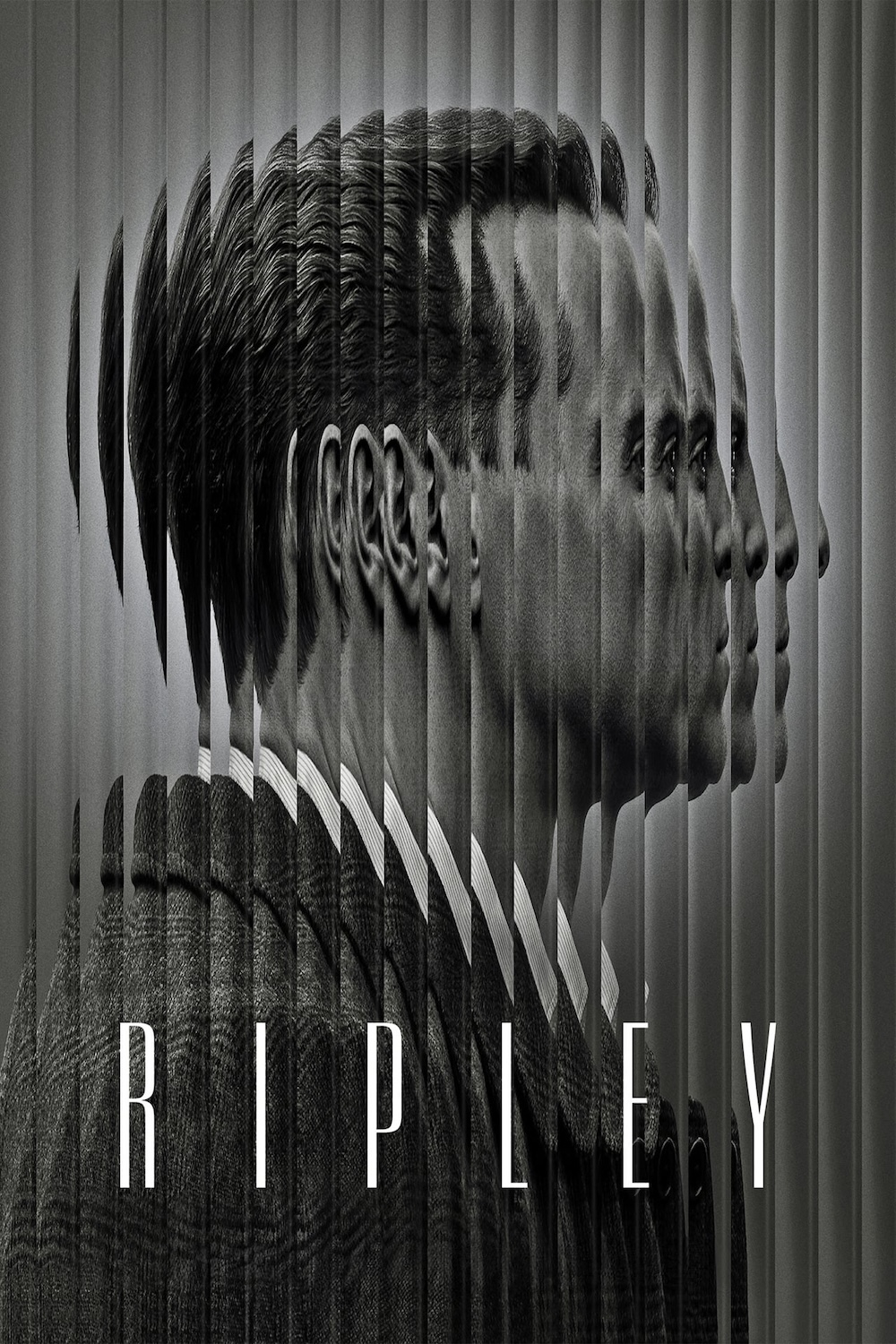

RIPLEY (2024)

A grifter named Ripley living in New York during the 1960s is hired by a wealthy man to bring his vagabond son home from Italy.

A grifter named Ripley living in New York during the 1960s is hired by a wealthy man to bring his vagabond son home from Italy.

When I heard Netflix was making a new series about Patricia Highsmith’s bon vivant serial killer, Tom Ripley—immortalised on film by luminaries like Alain Delon in Purple Noon (1960), Dennis Hopper in The American Friend (1970), Matt Damon in The Talented Mr Ripley (1999), and John Malkovich in Ripley’s Game (2002)—I was initially disappointed that the adaptation would be of the first novel, 1955’s The Talented Mr Ripley.

Highsmith’s Ripliad, the five novels chronicling Ripley’s adventures published between 1955 and 1991, contains such fertile ground for adaptation that it seems a shame to return to well-trodden ground. Of the five—the latter four being 1970’s Ripley Underground, 1974’s Ripley’s Game, 1980’s The Boy Who Followed Ripley, and 1991’s Ripley Under Water—my favourite by far is Game, perhaps simply because it has the highest body count as our dapper anti-hero garrottes and hammers his way through the mafia.

I first encountered the Ripley stories through Anthony Minghella’s aforementioned 1999 film starring Matt Damon. However, I found the novel less appealing upon delving into the Ripliad. The film portrays Ripley as a weak and tormented homosexual, opting for the least interesting and most literal interpretation of the character. While it broadly follows Highsmith’s original plot, it fails to capture the true essence of the ending—a triumph of evil over good. Ripley’s enduring appeal lies in his enigmatic charm. He’s closer to asexual than homosexual or heterosexual (as Highsmith bluntly stated, he appreciates male beauty but can “make it” in bed with his wife). Ultimately, his motivations are more straightforward: a desire to collect art, live comfortably in France, and host dinner parties.

All this groundwork leads us to Ripley, director Steven Zaillian’s new adaptation for Netflix. It stars current hot property Andrew Scott (All of Us Strangers) as the eponymous Tom Ripley. Early scenes depict him as a furtive and haunted confidence trickster, carrying out various mail frauds from an insalubrious address in early-1960s New York (pointlessly updated, it seems, from the novel’s 1955 setting). Almost as if rejecting the maximalism of the Minghella film, Ripley is shot in black-and-white and adheres to a ruthless minimalism. It features no more extras than are necessary (the streets of Italy are noticeably empty) and uses few wide shots beyond those required to establish the scene.

The plot of Ripley, for those unfamiliar, revolves around Tom Ripley, a young man with dubious employment and expert forgery skills. When a shipyard magnate mistakes him for one of his playboy son’s friends, he commissions Ripley to travel to Italy and convince Dickie Greenleaf (Johnny Flynn) to return and take up the family business. Living a life of idle luxury with his girlfriend Marge Sherwood (Dakota Fanning), Dickie has no intention of doing this. However, amused by Tom’s candour in admitting to the scheme, he invites his father’s stooge to stay. This proves to be Dickie’s first mistake, as the strange and intense Mr Ripley develops a burgeoning obsession with his host.

I suspect part of the reason for shooting in black-and-white was financial. The show has a spartan and minimalist quality that speaks to a functionality in its making, a sense that it was commissioned partly to provide Netflix with filler for their streaming service. Amusingly, the show opens with a prologue depicting a body disposal that doesn’t take place until much, much later in the narrative. That in particular feels like a Netflix decision; I can imagine an executive looking at Highsmith’s languid story of awkward conversations leading eventually to murder and saying that unless they begin with a tease of what’s to come, the audience will switch over to Keeping Up with the Kardashians.

Of course, the functionality isn’t a bad thing; it’s simply an observation about the programme’s raison d’être. The black-and-white also serves an artistic purpose, stripping back the lush, maximalist tones of Minghella’s Ripley, the most famous adaptation for general audiences. In doing so, it reflects Highsmith’s precise, economical, and gritty prose much more faithfully. This Ripley is far closer in tone to the book.

Andrew Scott is excellent in the role. His Tom Ripley is cold and supercilious when alone, but knows how to turn on the charm with the right people. He’s self-contained and reclusive, though harbouring such a deep psychological undertow that it would probably take years of therapy to work through, even if he were inclined. This tension lies at the heart of the character in his first adventure.

I particularly liked the show’s handling of Aunt Dottie, the maiden aunt who raised Tom after his parents drowned in Boston Harbour. We see her in a single flashback in the early episodes, undergoing a dental operation while Tom, in the present, writes a letter from his Italian trip, detailing his new financial prospects. This means he no longer has to rely on the pittance she (in his mind, at least) resentfully and maliciously sends him, a reminder of his inferiority and dependence. We never see if he sends the letter, filled with venom that was likely unexpressed in life but born from years of bitterness. So much backstory is implied in this brief scene: Tom writing the letter and Dottie being operated on. It’s likely Tom’s fantasy of her reaction to his letter, after its effects have truly sunk in.

The disconnected weirdness and just-enough-charm-to-get-by of Ripley are superbly done. The sexuality, too, is magnificently portrayed in subtle hints and asides, not declaring Tom as one thing or another precisely. (In the book, Tom intercepts a letter from Marge to Dickie complaining that although she initially thought he might be queer, she now thinks he might be too strange even for that.) I was initially surprised that the show didn’t try to modernise the setting and characters—Ripley for the smartphone generation—but there’s probably something inescapably mid-20th-century about this story, written when homosexuality was still a crime (and would remain so in the US technically until 2003, when the Lawrence v Texas case finally forced the repeal of sodomy laws). Tom’s potential attraction to men is depicted as part and parcel of his unsettling nature to the other characters, and that sexual tension simply couldn’t exist in an age where people are freer to be themselves.

Annoyingly, the show over-literalises the central murder scene. I wonder whether this is just something that films and TV need to do. I don’t want to be the “in the book…” purist, but Highsmith portrayed that murder as a cold and suddenly premeditated crime arising from a potent mix of opportunity and calculation. To put it simply, Tom decides to kill before he and his victim get in the boat, not after, and there are no dramatic “cards on the table” recriminations between them, which is what makes the murder so shocking. That said, Zaillian’s presentation of the scene is still much closer to Highsmith’s icy original vision than Minghella’s. Scott isn’t afraid to make Tom deeply dislikable here, a murderous leech, and once the theatrics are dispensed with, his careful arrangement of the scene is intriguing. There’s also a fantastically eerie minimalist shot of the corpse disappearing into the ocean void.

Ripley is, in one sense, a cheap and mercenary adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s original novel. It’s a low-budget rush job made for the streaming age. However, thanks to the talent of those involved and a deeper respect for Highsmith’s plot than some other adaptations have shown, it’s a fun and creepy psychological thriller.

USA | 2024 | 8 EPISODES | 1.78:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

writer: Steven Zaillian (based on the novel ‘The Talented Mr Ripley’ by Patricia Highsmith).

director: Steven Zaillian.

starring: Andrew Scott, Dakota Fanning, Johnny Flynn, Eliot Sumner, Margherita Buy, Maurizio Lombardi, Kenneth Lonergan, Ann Cusack, Bookem Woodbine, Louis Hofmann, Fisher Stevens & John Malkovich.