BOYZ N THE HOOD (1991)

Follows the lives of three young males living in the Crenshaw ghetto of Los Angeles, dissecting questions of race, relationships, violence and future prospects.

Follows the lives of three young males living in the Crenshaw ghetto of Los Angeles, dissecting questions of race, relationships, violence and future prospects.

Los Angeles, if the movies are to be believed, has long been in love with itself. It’s an infatuation cinema’s only facilitated and emboldened. Since L.A was decided upon as the ideal base for the film industry in the early-20th-century (owing to its year-round sunshine and non-unionised labourers, easily exploited by the powerful), filmmakers haven’t been shy to depict their homeland. Hagiographies ranged from musicals to noirs, charting maps made up of glamorous Hollywood streets and darkly beautiful back alleys.

But if this cinematic map was vivid in its downtown jungle or its backlot mazes, it surely had some dramatic grey areas—sections with question marks. Released in 1991, Boyz N the Hood blasted a searchlight into that grey area. Predominantly black neighbourhoods such as Inglewood (where the film’s set and shot), which comprise much of South Central Los Angeles had rarely captured by major studio producers. As ignored in movies as it was in life. Films such as Charles Burnett’s influential drama Killer of Sheep (1978) looked at these areas with stunning insight, but where Burnett’s film was an indie project made for just $10,000, Boyz N the Hood was produced by Columbia Pictures, who gave director John Singleton $6.5M to realise his story.

One can sense this was Singleton’s debut, in the way one can tell you’re hearing a band’s first album. It’s rough around the edges but filled with that youthful, powerful energy (Singleton was 23 at the time), desperate to include everything they’ve been saving in case this is the only chance they’ll get to speak their truth to the world. It’s hard to fathom the unfair responsibility that might’ve been on Singleton’s shoulders when undertaking such a project. Not only was this his first chance to prove himself as a writer-director, but the film came saddled with an unrealistic critical expectation unique to black cinema: that it must speak for the entire black experience. Also that it must be funny, yet serious…. celebrate, but also condemn… be transporting, yet relatable. It had to include twice as much as any other coming-of-age film because it had the extra burden of possibly being the only film of its kind. It was charting an area of a map never explored by major cinema. It was a first impression.

The film is direct in a way that might be considered on-the-nose if it weren’t so impassioned and persuasive. It opens not with a visual but a sound: gunfire and screaming. A young boy’s voice cries “they shot my brother”. A wail of sirens follow. We’re made to listen before we look, a powerful decision that channels the nameless and faceless dead who’ll never be featured on the evening news or tomorrows papers. We’ll be taught how to listen throughout the film, but first, as the opening image of a street-sign tells us, this must ‘STOP’.

Young Trey Styles (Desi Arnez Hines II aged 10, Cuba Gooding Jr. aged 17) is something of a blank canvas, another part of that uncharted map. Cuba’s Trey is never quite smooth enough to hide his naivety, nor tough enough to mask those deep-seated wounds inflicted in childhood. He wants to teach but he hasn’t finished learning yet. In an early scene, the young Trey stands at the front of a class and teaches his schoolmates about Africa—the place, he says, where they all come from. He stands proud and forceful, even when one kid scores points with his friends by making fun of Trey and his lesson. It doesn’t take long to descend into a fist-fight.

Boyz N the Hood is compelled by the desire to teach, to ask its audience not to turn on each other and instead, as its tagline says, ‘increase the peace’. In keeping with this, Trey has to be a blank canvas. He has to have that young spark of life-threatening to zap his world—either with a life of learning and teaching or with violence. Put simply, he has to have all these options before him, so we can see him make his choices and understand why. The brilliant empathy of Singleton as a director means he colours with nuance and perspective, asking the question “how did we get here?”

Surrounded by people with wildly different trajectories, Trey could follow one just as easily as another. He might follow his father, Furious Styles (Laurence Fishburne), and stay in the neighbourhood to educate his friends and try to improve their self-worth. He might follow his mother, Reva (Angela Bassett), get an education and move away to a house glimpsed briefly, perhaps in the hills of L.A where Inglewood’s just a distant glowing light in the night. Or he might get in trouble with the law like his friend Doughboy (Ice Cube).

Singleton’s script never condemns its characters for their choices and goes to great lengths to hint at the reasons for the circumstances. Brutal, violent police officers threaten Trey’s life, seemingly to just exert power; extreme poverty and drug abuse are rife; plus there’s almost total governmental abandonment in the ‘hood. The results are a disenfranchised people, desperate to regain marginal power, often in the forms of weapons.

The film’s most stirring speech comes from Furious Styles, whom the neighbourhood come to listen to, regardless of whether they agree with him or not. He asks them why they think there are gun and liquor shops on every street corner in the hood, while there are none in the suburbs. “They want us to kill ourselves”, he states. It’s a powerful statement, one that almost forces you to grapple with it. And it’s one that is hard to rebuke. What works so marvellously about these ‘teaching’ moments is how they’re in keeping with who Furious is and what he cares about. And while he’s a gifted speaker and boundlessly wise, the scene makes us question something we’ve seen him do. Was it not Furious who blindly fired his pistol at an intruder earlier in the film?

Singleton allows for complications, contradictions, and the messiness of human beliefs. You might say one thing and do another. You might change what you believe in extreme circumstances. After all, like Furious shooting to kill, Trey later arms himself with a gun and sets out to find the people who killed his friend. Unless you’re in this situation, and unless you’ve grown up in these places, you can never quite say for certain what you might do in the moment. Rationality and teachable moments seem to fall away when blood-soaked human emotions take charge.

It’s remarkable, then, that amongst the trauma and heartbreak, there’s a gentleness and looseness to Singleton’s movie that feels impossibly laid-back and seductive. Many of the film’s strongest sequences revolve around excellent inter-character dynamics, a hangout approach that pulls up a chair and sits alongside a group of people just living their lives. One scene set during a barbecue effortlessly gathers most of the film’s main characters in one place and introduces us to the people they’ve become. We learn a lot from their interactions, but ultimately it’s a scene about having a good time—shooting the shit with your friends, playing card games and living, regardless of what lurks outside the back yard, or the cars which roll menacingly along the street with its windows down.

It’s scenes such as these which bring to the foreground just why Singleton’s film has been so beloved for so long. Aside from the cultural relevance and timeless urgency of the film, it’s this brilliant life and charisma that it maintains. It’s introducing us to these fresh faces–Cuba Gooding Jr., Regina King, Ice Cube, Morris Chestnut—and letting them be exactly as funny, petrified, kind, bullheaded, and complex as they deserve to be. It’s understandable why Boyz N the Hood is seen as an ‘issue’ film, but it’s a pity… because this downplays the fact it’s also about family, strength, and the way human relationships are strained by circumstance.

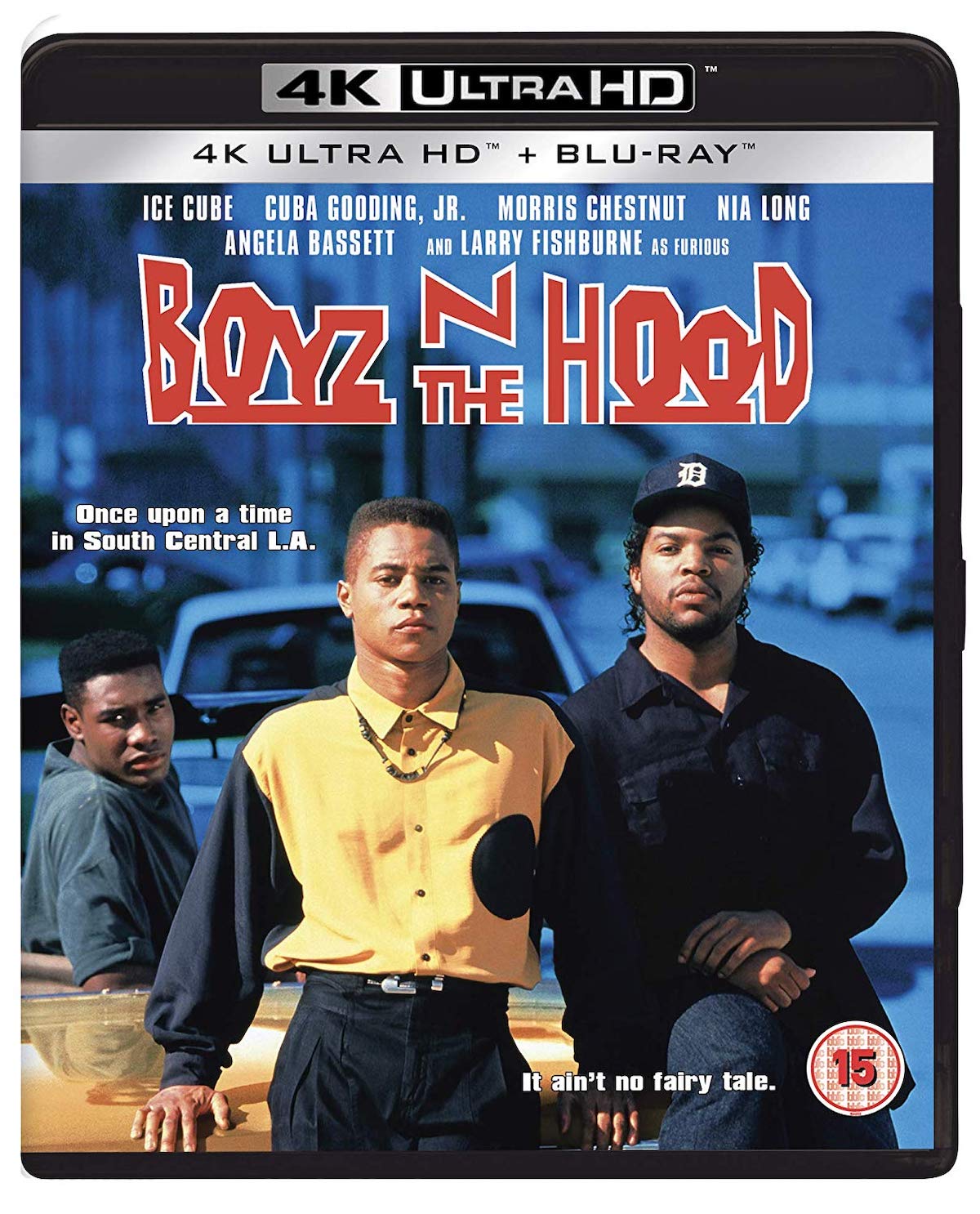

Boyz N the Hood remains an important milestone of 1990s US cinema, and Sony Pictures’ new 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray release helps the movie feel as fresh and vital as ever. The richness of Singleton’s images, steeped in textural grain, is thankfully not lost in this 4K upgrade. The film feels just as sweaty, aching, and tangible as it ever did, and the stunning clarity provided in this version is careful not to strip away the film’s physicalness. The orange California sunsets look vibrant and engulfing, while it’s fun picking up on new details. This time around, I noticed the young guys arguing in the background after the softer-hearted of the two decides to give Ricky his football back. It’s a small touch, but a detail that Singleton cared enough to include, and a 4K release allows us to pick up on those nuances. The Dolby Atmos audio track is rich and layered, which counts a lot for a film such as this, where sound—be it music, ferocious dialogue or gunfire—is at its core. This is the best the film has ever looked or sounded, but its greatest achievement is that it still feels like the movie I loved and watched a hundred times before on VHS.

writer & director: John Singleton.

starring: Ice Cube, Cuba Gooding Jr., Morris Chestnut & Laurence Fishburne (as ‘Larry Fishburne’).