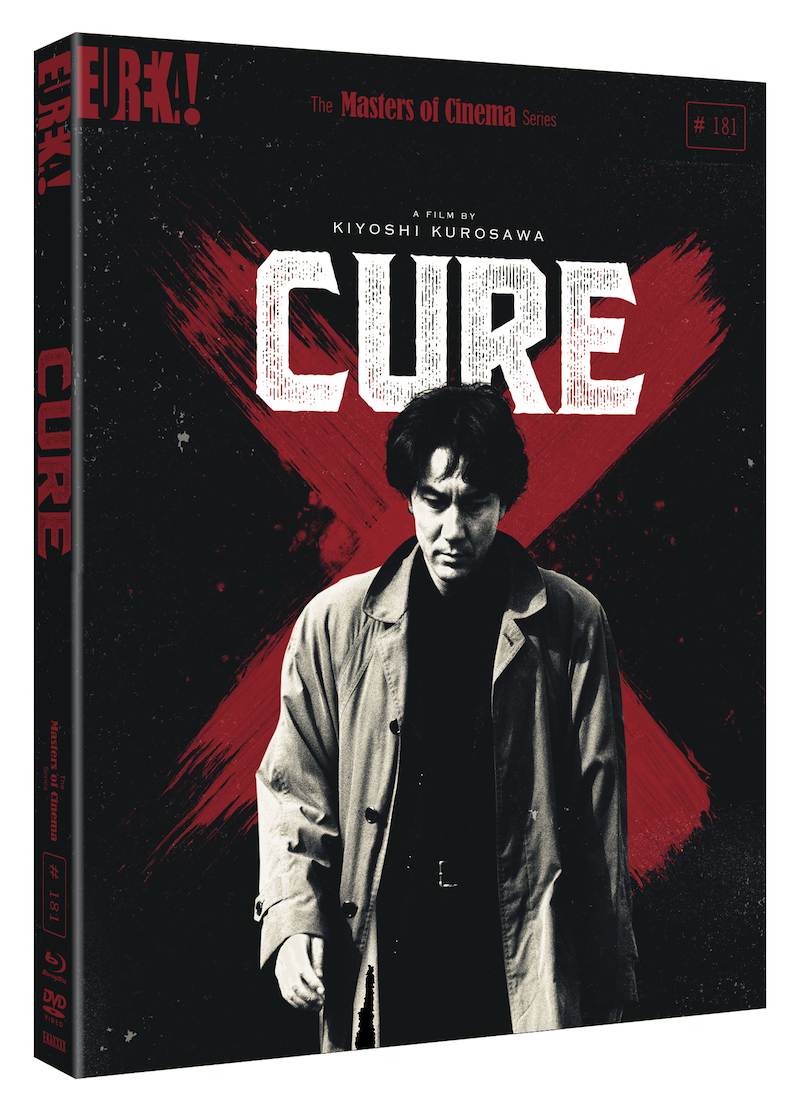

CURE (1997)

A frustrated detective deals with the case of several gruesome murders committed by people who have no recollection of what they've done.

A frustrated detective deals with the case of several gruesome murders committed by people who have no recollection of what they've done.

Writer-director Kiyoshi Kurosawa remembers a TV news report about a seemingly normal man who committed a heinous murder. The killer had been living in a nice middle-class neighbourhood and never showed any signs he was capable of such an evil act. Those who knew him were shocked he could have kept it hidden so well.

Kurosawa was struck by the thought that perhaps he’d not ‘kept it hidden’ because he hadn’t always been evil. Had something changed him from the normal, everyday guy he appeared to be, into a cold-blooded killer? Just maybe, he thought, any so-called ‘normal’ person has the potential for evil. It’s not something that resides in the other, the outsider, the psycho, but something that could be triggered within all of us. This chilling premise provided the seed for Cure, his 1997 landmark psychological-thriller, and it’s this concept that makes the film so insidiously scary.

It’s deceptively low-key with an art-house vibe that sucks you in and lulls audiences into a false sense of security. In Cure, evil isn’t a threat from the outside, but from within. What would it take to turn your postman into a killer? Or you? The clinical, matter-of-fact approach demonstrated by Cure’s killers is unsettling because it shows desensitised individuals living out a base desire they’d been denying themselves. They are not portrayed at all as the romanticised psycho-killers we know form our Hollywood thrillers.

Although Cure was the mainstream cinematic debut for Kurosawa, he’d already made some 20-plus straight-to-video movies, starting out with so-called ‘pink’ films (exploitation movies with an element of soft-core titillation) and moving on to a long list of Yakuza films starring Shô Aikawa, an actor synonymous with the genre. Kurosawa had repeatedly proven to be a reliable, no-nonsense director who could deliver on time and within budget, and this reputation eventually allowed him to make the more experimental, genre-skirting Cure.

Upon its release, Cure did moderately well, but distributors and audiences alike were not sure what to make of it. It had the feel of an art movie, the story of a psychological thriller, and the lingering effects of a horror. It wasn’t widely seen outside of its native Japan, but the intervening decades have confirmed it as one of the most formative and defining films of the emergent J Horror scene that later produced Ringu (1998), Ju-on: The Grudge (2002), and other unsettling, monosyllabic classics. So, it’s great to see it joining Eureka’s Masters of Cinema Series, and about time it was given a proper release outside Japan. Incredibly, this is the first time it will be available in any home media format in the UK.

Kurosawa’s use of locations is striking and gives the film an almost placeless, timeless feel. Some of the tracking shots through derelict, colour-drained interiors, their wide floors rippling with puddles, are reminiscent of Tarkovsky. Apart from a few aerial shots of city back streets, there’s no real clue as to which city we’re in.

I have a feeling the street-level settings would be all too familiar to residents of Tokyo, but I’m sure they would find the sense of desolation and isolation disconcerting. Where are the expected crowds of bustling commuters? Instead we see lone figures cross long spans of bridges or walk through dingy subways. The labyrinthine back alleys seem dream-like and deserted, evoking images of evacuated, post-apocalyptic cities. The otherworldly emptiness of the night streets reminded me a little of Dark City (1998), another film that explored similar ideas of shifting identity and hypnotic manipulation.

We first meet the mysterious Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) as he emerges from the hazy distance to wonder a long empty stretch of beach, until he comes across another man sitting on a dune. He asks a series of questions about where they are and, more disturbingly, who they are. Of course, we don’t know who Mamiya is at that point, or what his connection to the murders may be. Only when the kindly man from the beach takes the amnesiac to his home, does he discover a name tag on an article of clothing, which Mamiya promptly tears off.

We witness one of the shockingly matter-of-fact murders in the opening few minutes as a man walking through a grimy underpass pauses to rip a loose water pipe from the wall. A little later, he uses this to murder a young woman with sudden, repeated blows to the head. When Detective Takabe (Kôji Yakusho) and his team arrive at the blood-spattered crime scene, we learn that the woman was ‘finished off’ by having an ‘X’ carved across her throat and torso. This signifier links a series of seemingly unconnected killings that is already testing the troubled detective’s resolve.

There has been a spate of murders where the perpetrators apparently don’t understand their own motives and have no clear memories of their crimes. Often it is a loved one or close colleague that they have killed. They are unable to explain the ‘X’ motif cut into their victims. Doctor Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), the criminal psychologist on the case, has interviewed them all and found each one to be sane and rational. It quickly becomes clear that a bond has already developed between the detective and the doctor and they have been working on this confounding case in close partnership for a while.

So, what could this ‘X’ symbol indicate? We use the mark to represent a kiss, or a wrong answer, passages marked for deletion, multiplication. Chances are there is one, top right, on the screen in front of you right now…

There is nothing else to connect the cases until a beat police officer coldly executes his partner with a bullet to the back of the head. He shows no remorse, but under hypnosis, he is compelled to make the ‘X’ sign, without knowing why. It turns out he had dropped an amnesiac off at a hospital shortly before committing the murder. When the doctor (Yoriko Dôguchi), who treated the mysterious young man, then kills and cuts her victim open with an ‘X’ shaped incision, the police have their first significant link. The narrative then becomes a battle of wits between Detective Takabe and the young Mamiya.

The scenes between them are intense, finely crafted, and superbly acted, as we see the detective’s sanity eroding. Understandably, Takabe’s angered by Mamiya’s lackadaisical manner and how he seems to know too much about his personal life. The Detective is already under stress because of his wife’s gradual descent into mental illness, but he has been battling to keep his professional and personal life separate. Mamiya plays on the detective’s fears and insecurities and Doctor Sakuma has to intervene for the sake of his friend’s sanity…

It seems that Mamiya may be a psychology student who dropped out and went missing months ago. The strange items found in his apartment include a desiccated monkey and books on occultism. Among his impressive collection of esoteric writings are the works of Franz Mesmer, the 19th-century scientist and mystic who explored what was called ‘animal magnetism’, referred to in Japan as ‘soul conjuring’, and what we call ‘mesmerism’.

Mamiya now seems to possess the power to convince anyone to do anything simply by whispering to them, including letting him out of his secure cell in psychiatric hospital. In this way he is similar to the character of Hammersmith, played by Richard Burton in the failing Faustian allegory, Hammersmith is Out (1972), or perhaps John Morlar, also played by Richard Burton in the classic The Medusa Touch (1978). Unlike Burton, whose screen presence projects an unstoppable strength of will, Masato Hagiwara underplays Mamiya, almost as if he may also be a victim of hypnosis himself, a cypher of some greater power, and is all the more unnerving as a result. In many ways, the character has echoes of Charles Manson, who also seemed able to manipulate others and inspire them to murder.

It’s hinted that Mamiya may have been ‘mesmerised’ himself, merely by reading the texts. Later, Doctor Sakuma manages to trace the earliest known film of hypnotism being carried out in Japan. The footage is faded and grainy and the hypnotist is careful not to show his face, Sakuma explains this is because ‘soul conjuring’ was outlawed at the time, under the Meiji Shogunate. The clip does appear to confirm a link with the ‘X’ motif—which I won’t go into here—and implies that, perhaps, the film itself can ‘infect’ the viewer with the urge to kill. This idea, of an image or film carrying and implanting subliminal information, has since become a recurring theme in modern horror, most notably in the Ringu series.

Cure remains fresh and unique and would certainly appeal to contemporary audiences, perhaps even more now we have grown used to the J Horror vocabulary. That genre did not exist when Kurosawa made his film, though he has continued to contribute to it ever since with films like Pulse (2002) which explored some similar themes, Loft (2005), and more recently Creepy (2016).

The new 1080p Blu-ray edition of Cure from Eureka! finally does the film justice and treats it with deserved respect, recognising the indelible contribution that Kurosawa has made to the horror genre. There are two archival interviews with the director included, one revealing his own thoughts on making Cure, and the other a more general overview of his extensive film career. He comes across as a completely unpretentious and genuinely enthusiastic filmmaker. There’s no audio commentary, but another interview included with this new release is with critic Kim Newman, who has long championed the film. He analyses some of its subtexts and compares it to the films of Val Lewton and Larry Cohen, attempting to place it into a context that may appeal more to western audiences.

writer & director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa.

starring: Koji Yakusho, Tsuyoshi Ujiki, Anna Nakagawa & Masato Hagiwara.