INVESTIGATION OF A CITIZEN ABOVE SUSPICION (1970)

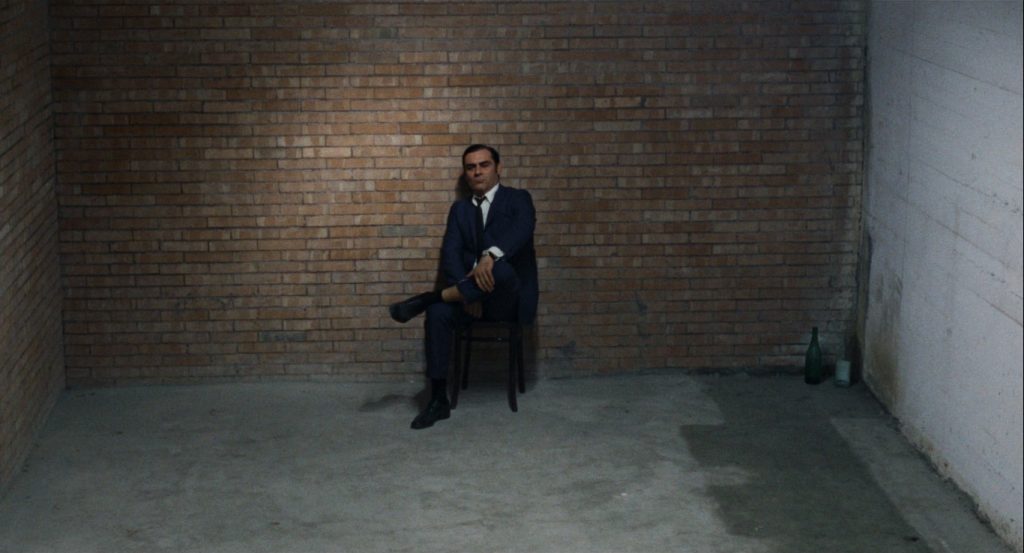

A chief of detectives, homicide section, kills his mistress and deliberately leaves clues to prove his own responsibility for the crime.

A chief of detectives, homicide section, kills his mistress and deliberately leaves clues to prove his own responsibility for the crime.

I only knew of Elio Petri’s Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion by reputation, as it’s generally thought to be the director’s masterpiece. Not only that, Gian Maria Volontè’s performance in the lead has been hailed as the actor’s finest. So I was delighted to learn that this 4K restoration, which has been available in the US for seven years or so, is finally getting a UK Blu-ray release as the latest addition to the Criterion Collection. What’s more, it lives up to expectations… by not quite delivering what I was expecting!

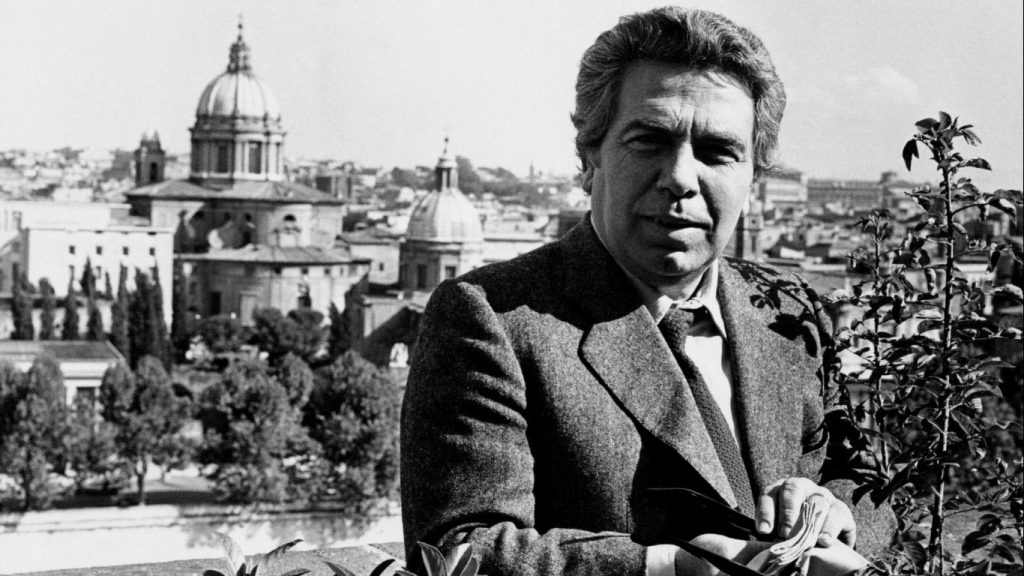

If you’re unfamiliar with the work of maverick Italian director Elio Petri, it’s difficult to predict what you’re going get when you sit down to view one of his movies. He wrote and directed 11 features, a handful of documentaries and television episodes, and has penned many more screenplays. I’ve only managed to view a couple of his movies, but it seems that no two are alike, as he’s known for continually experimenting with style and flitting from one genre to another.

The film he made immediately prior to Indagine su un Cittadino al di Sopra di Ogni Sospetto / Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (henceforth Investigation) was Un Tranquillo Posto di Campagna / A Quiet Place in the Country (1968), which is considered a proto-giallo with supernatural undertones, starring Franco Nero and Vanessa Redgrave. His next film was to be La Classe Operaia va in Paradiso / The Working Class Go to Heaven, aka Lulu the Tool (1971), which again starred Gian Maria Volontè, this time as a factory worker who suffers a minor industrial injury, triggering him to become a left-wing activist and organise strikes for workers rights.

These three very different films confirmed Petri as one of the most interesting and unconventional voices in Italian cinema, and yet he remains overshadowed by contemporaries like Federico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. Perhaps this is because he deliberately kept his films accessible to the mainstream cinema audience, employing familiar narrative conventions more often seen in Hollywood movies.

That’s not saying his films were any less intellectual or meaningful, but they were often more relevant—Investigation being a great example. Communicating complex ideas so clearly through eloquent visual language meant he was often at odds with the Italian establishment and butted up against the super-strict censorship several times. Operating against the tumultuous political backdrop of post-war Italy, many of his fellow filmmakers hid their messages behind arty pretense. Petri left little doubt that he was a radical with Communist sensibilities and, although he left the Party in 1956, he remained staunchly anti-capitalist.

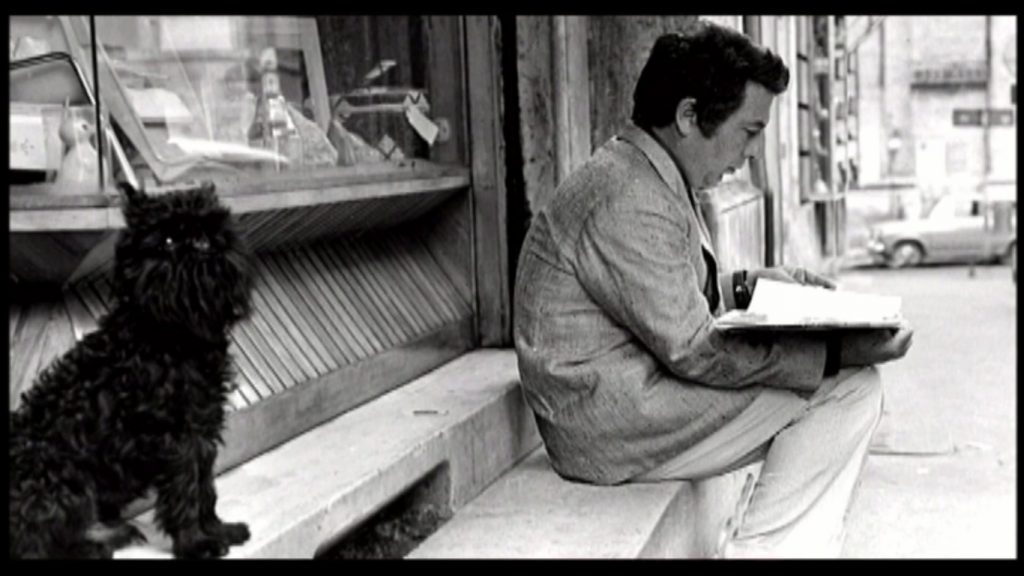

Petri’s favourite leading man, Gian Maria Volontè, was often his creative collaborator and political co-conspirator, and both were involved with protest groups. His audacious and precise performance as the titular citizen above suspicion is nothing short of outstanding. Playing his psychologically juvenile and unbalanced role as a kind of Mussolini pastiche, he adds layers of complexity to a scathing portrait of a damaged man corrupted by the power entrusted to him.

Normally, following a story from the point of view of an unpleasant character can be a challenge, especially when there are so few likable characters to be found elsewhere in the story. But Volontè is consistently compelling and ensures the proceeding remains eminently watchable. Audiences outside Italy may know the actor best for his appearances in Spaghetti Westerns, most memorably as villains for Sergio Leone in Fistful of Dollars (1964), and as the chilling psycho with the musical pocket-watch in For a Few Dollars More (1965).

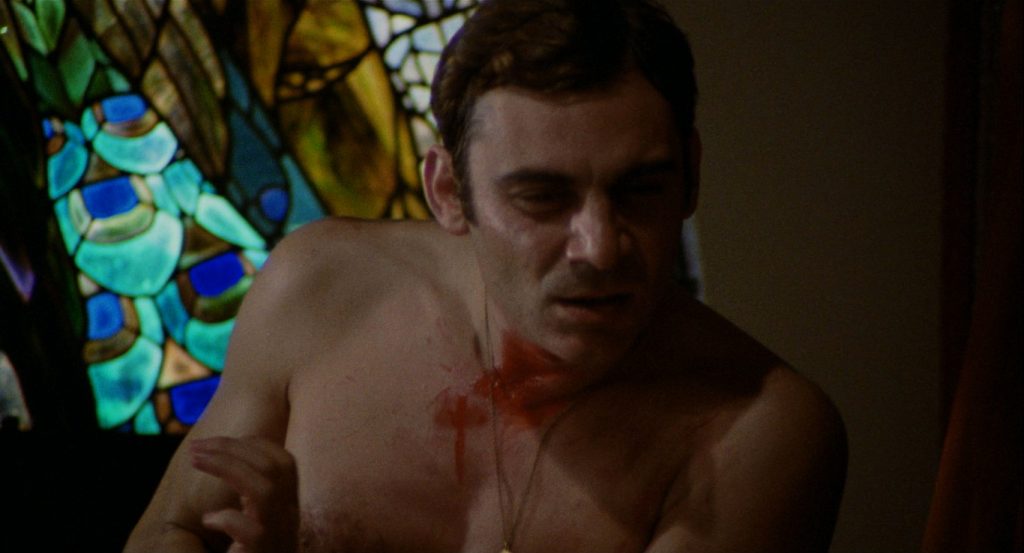

The opening sequence of Investigation could easily have come from a classic Dario Argento giallo. Accompanied by a distinctive Ennio Morricone theme, a man (Gian Maria Volontè) loiters for a moment outside a grand building, looking up at its two murals of ‘Justice’ and ‘Science’, before meeting his mistress (Florinda Bolkan) in her stylish art nouveau apartment, complete with stained glass features and archways.

The set-dressing is rich and detailed. There’s even a couple of creepy dolls thrown in. She greets him with a question: “how are you going to kill me this time?” To which he replies: “I’m going to slit your throat.” Turns out he was just being honest. It’s worth noting that Argento was yet to make his directorial debut.

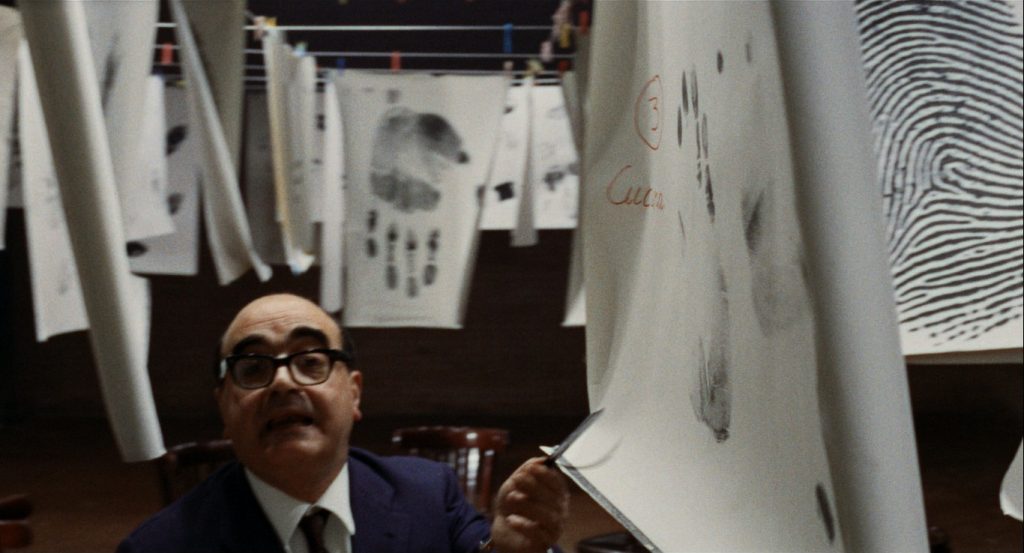

We don’t know who these people are as we witness the man coldly murder the woman during their lovemaking. He’s obviously planned this out in advance and, as we’re shown precisely how he perpetrated the crime, it’s reminiscent of a Columbo story. He then proceeds to meticulously manipulate the crime scene. He adds evidence, setting-up specific clues, such as looping a thread of blue silk under one of his victim’s fingernails and very deliberately leaving a trail of bloody footprints. He’s sure to place a wad of cash on display whilst pocketing some jewellery. Then he takes a rest before phoning the police to report the murder and leaves with two bottles of champagne lifted from the fridge.

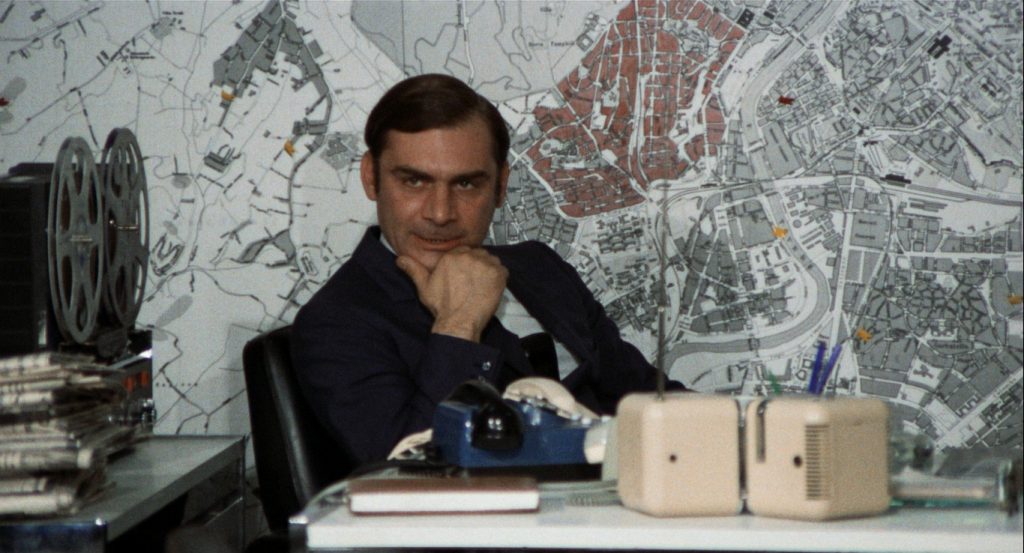

Still carrying the bubbly, he arrives at the Police HQ to celebrate with his colleagues. Apparently, he’s just been promoted from Chief of Homicide to Head of the Political Division. With a dynamic camera tightly following him, he alternates between praising and belittling his fellow detectives with lots of theatrical shoulder gripping, hair ruffling and cheek pinching. During this lively sequence news of the murder of one Augusta Terzi reaches him, a courtesan with no visible means of support linked to several high-profile political persons…

As part of the hand-over, he snubs one of his subordinates, Mangani (Italian pulp cinema stalwart Arturo Dominici), and hands the case to Biglia (Orazio Orlando). The whole scene introduces the main players and establishes how much the Chief enjoys flagrantly abusing gradients of power—the central theme here, in both the personal and political arenas.

His inaugural speech as Head of the Political Division could well have been complied from a ‘best of fascist despots playlist’ and underlines everything the film will be addressing either directly, or in the form of a Kafkaesque parable of crime and (lack of) punishment.

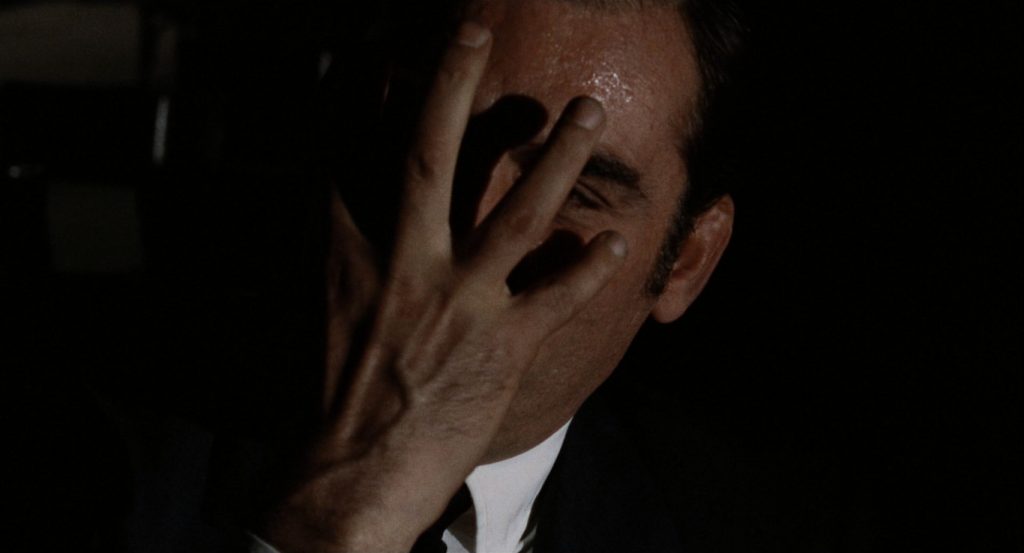

At first, the Chief tries to frame the absent husband (Massimo Foschi). Then decides to scapegoat a left-wing activist (Sergio Tramonti). He begins to realise that shifting blame onto others doesn’t mean that he’s truly gotten away with murder and outwitted his colleagues. So, he becomes obsessed with proving that he’s indeed ‘above suspicion’ and manipulates evidence to incriminate himself. However, it seems that witnesses suddenly have alibis and evidence against him is disbelieved or destroyed… American Psycho (2000), based on the novel by Bret Easton Ellis, repurposed what is basically the same plot but with added murders as a critique of 1980s yuppie culture rather than 1960s totalitarianism.

Although Petri’s roots in Italian neo-realism are evident, this isn’t a realist film and progressively becomes more nightmarish until a final breakdown of believability crosses the border between thriller and absurdist satire that manages to feel just as edgy 50 years on from its release. The schizophrenic finale may leave some viewers baffled, but at no point on the journey would they’ve felt bored!

Petri keeps the narrative pace lively, relying heavily on the central performances and the inventive camerawork of cinematographer, Luigi Kuveiller, with whom he’d already worked on his two preceding productions: We Still Kill the Old Way (1967), which also starred Volontè; and A Quiet Place in the Country.

Kuveiller places the viewer right in the middle of the action. Though just as often uses the camera voyeuristically, giving the impression of surveillance with very high angles, even showing the action from directly overhead on occasions. He would go on to become a prolific and influential cinematographer working with, among many others, Lucio Fulci on Una Lucertola con la Pelle di Donna / A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin (1971), which again starred Florinda Bolkan; and Dario Argento on Profondo Rosso / Deep Red (1975).

Several memorable motifs from Investigation recur in the films of Argento, who was certainly influenced by the work of this fellow film-critic-turned-director. The psychopathic monologues delivered and played back on tape are echoed in the opening of Tenebrae (1982), and both films contain scenes where a female victim is gagged with crumpled paper. The use of flashbacks to reveal backstory and establish irrational motivations are also prominent.

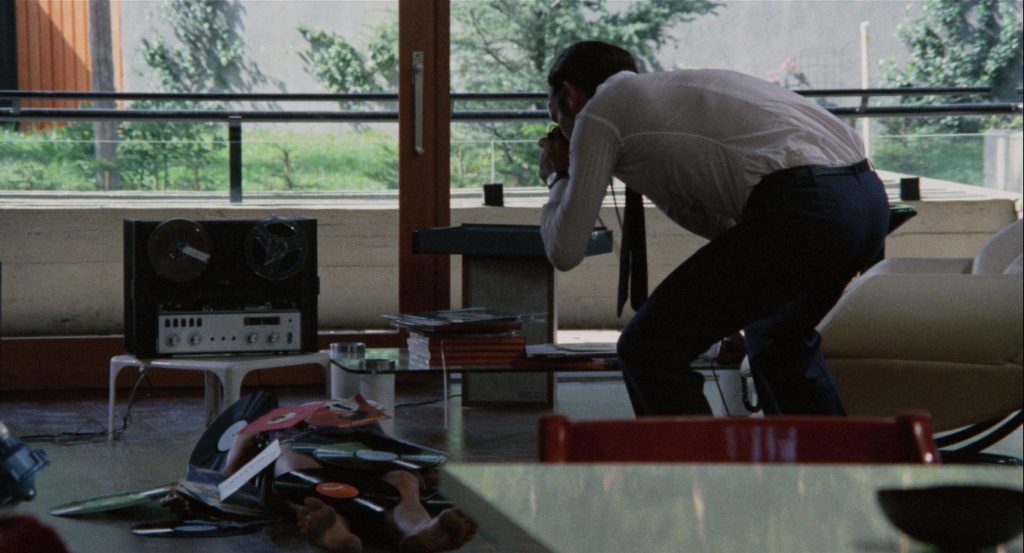

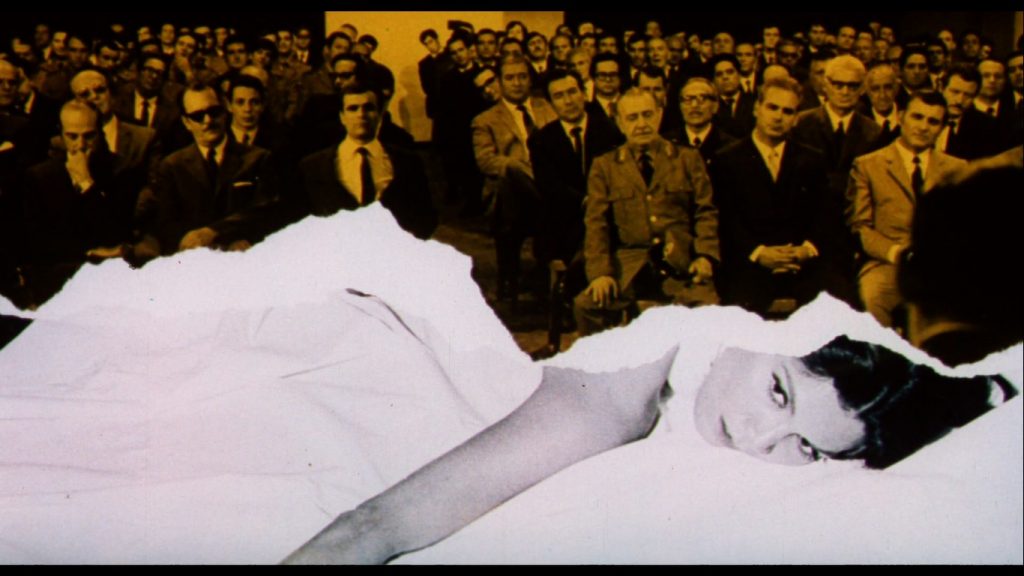

Here, the relationship between Volontè’s and Bolkan’s characters is told piece-meal through flashback and could almost be a catalogue of rejected giallo scenarios! The police chief re-enacts many of the sexualised murders he has investigated, finding them increasingly arousing. Egged-on by his equally deranged mistress, he pretends to kill her over and over again, recording their reconstructions of how the bodies were found in a fusion of fashion and forensic photography. This thread part inspired Luciano Ercoli’s Forbidden Photos of a Lady Above Suspicion (1970), hence the intentionally referential title.

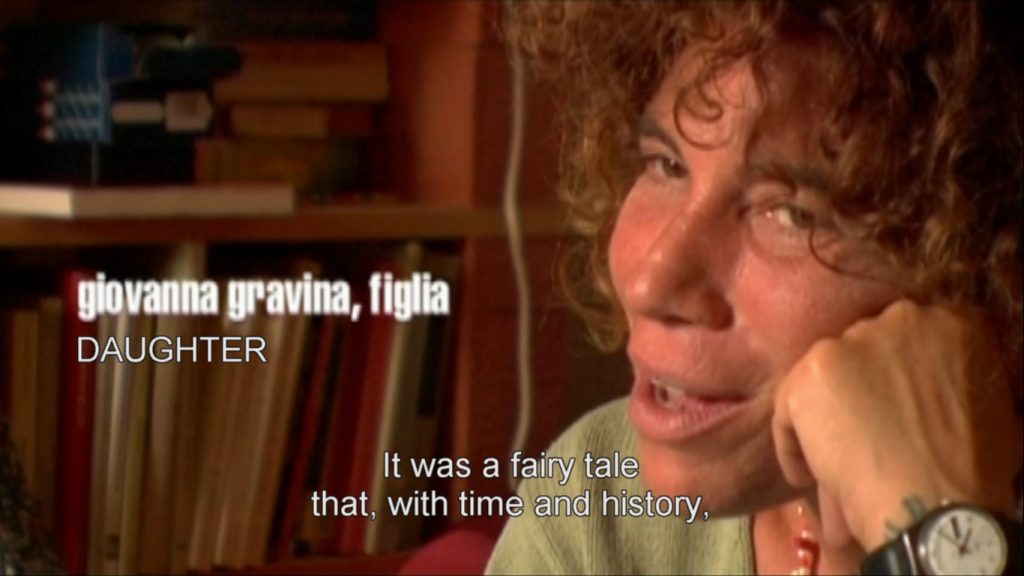

Although Volontè delivers a tour de force, Bolkan certainly holds her own in the intimate scenes they share. Their energies bounce off each other and her fiery character is just as surprising and textured. This was a fairly early appearance in her long and varied career—I remember her best for James Clavell’s classic The Last Valley (1971) in which she plays the doomed witch, opposite Michael Caine. She went on to appear in several important Italian gialli, and her portrayal of a similar character in Lucio Fulci’s Non si sevizia un paperino / Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), is particularly strong, edged with tragedy and pathos. So too is her ambiguous lead in Luigi Bazzoni’s intriguing, Le Orme / Footprints on the Moon (1975).

Investigation is precisely of its time, reflecting the socio-political tensions that sparked-off the Battle of Valle Giulia (where thousands of militants, mainly students from both left-and-right-leaning factions, clashed with a massive police presence), and its narrative unfolds amid the events leading up to the Piazza Fontana bombing of December 1969, making the film doubly prescient as the production had wrapped by then.

Many of the protest movements that had been gathering momentum thought the sixties seemed to explode during 1968. The US had violent race riots added to its protests against the Vietnam war. Czechoslovakia had its ‘Prague Spring’. Poland suffered a neo-Nazi uprising with anti-Semitic purges. There were student occupations and general strikes across France that very nearly sparked a civil war during the period now simply referred to as ‘May ’68’ when the French government temporarily dissolved, and the entire economy was suspended. The ‘Troubles’ escalated in Northern Ireland.

Investigation addresses these events, searching for meaning and motivations by boiling-down the broader political scenarios to the personal level of a single character. It’s quite an achievement as, whilst we examine and debate the character’s motivations, they are changed by their own actions and so those motivations mutate…

It may reach a point where it becomes a bit too clever for its own good but will certainly provoke debate, encouraging us to question the establishment around us and our personal responses. Half a century on and, rather sadly, recent events have proven that kind of awareness is something our society is still in dire need of!

Although largely overlooked nowadays, Investigation made quite a splash on release, popular with audiences and critics alike. It won a few prestigious awards including an Academy Award for ‘Best Foreign Language Film’, the ‘Grand Prix Jury Prize’ at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, and the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for ‘Best Motion Picture’. Cannon proposed a remake during the ’80s and Paul Schrader was tasked with the rewrite and Sidney Lumet and Andrey Konchalovskiy were possibles to direct. Al Pacino and Christopher Walken were tipped to star. It never made it to production, which is no great loss as it would’ve probably proved superfluous with the surprisingly modern original still bearing up so well.

ITALY | 1970 | 115 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

director: Elio Petri.

writers: Elio Petri & Ugo Pirro.

starring: Gian Maria Volonté, Florinda Bolkan, Gianni Santuccio, Orazio Orlando, Sergio Tramonti, Arturo Dominici, Massimo Foschi, Aleka Paizi & Vittorio Duse.