THE WORKING CLASS GOES TO HEAVEN (1971)

A factory worker gets his finger cut off by a machine, and the accident causes him to become more involved in politics...

A factory worker gets his finger cut off by a machine, and the accident causes him to become more involved in politics...

Elio Petri’s The Working Class Goes to Heaven / La Classe Operaia va in Paradiso is perhaps the maverick director’s most overtly political piece. It deals with the antagonism between exploited workers, middle management, factory owners, unions, student-worker coalitions, the middle-class extreme left, anarchist provocateurs, and the police… certainly a volatile mix! Despite being very definitely situated in an exact time and place, an Italian factory town in the early-1970s, its damning deconstruction of industrial capitalism and class conflict has lost none of its relevance today as we see a resurgence of right-leaning populist ideology around the globe. So, this excellent 2K restoration of the film on Blu-ray demonstrates insight on behalf of Radiance Films, a newcomer to the boutique market for cult classics and world cinema run by seasoned cineaste Francesco Simeoni, the erstwhile content director for Arrow Films.

The Working Class Goes to Heaven is a difficult one to sum up. A dystopian critique of societal injustice with a problematic protagonist redeemed through astute character studies tempered by dark satire. It tackles highly complex issues but retains clarity by zooming in on personal stories playing out against the broader socio-political canvas. It’s so realistic it could be considered cinema verité, at least in part. It’s also frenetic, experimental, and visually expressive. Look out for a gorgeous homage to the famous seventeenth-century painting known as Bruegel’s Winter, when riot police pursue panicking protestors through a starkly beautiful, winter-bright snowscape. Petri’s cinematographer of choice, Luigi Kuveiller isn’t afraid of contrast and manages claustrophobic dark interiors equally well…

The first thing that leaps out of the darkness is an auditory attack of tight brass horns blaring to a clattering industrial rhythm—the ‘music’ of machinery. Ennio Morricone’s experimental, often overly dramatic score will build around this sound sculpture throughout, punctuated with slurred sequences of almost recognisable tunes. I detected a pastiche of Irving Berlin’s 1936 jazz standard “Let’s Face the Music and Dance”, that reprises in seemingly more and more demented deviations as the cracks start to craze Lulù Massa (Gian Maria Volonté) who’s already tired as he wakes in the darkness ahead of his alarm clock, disturbed by the snores of Lidia (Mariangela Melato) with whom he shares a bed.

Lulù complains of his headache, ulcers, and lack of libido due to his seemingly endless toil at a lathe making components at the local factory. At work, Lulù is at one with his machine and we learn that he’s been in the same job since leaving school at 15. He’s by far the most efficient worker on the factory floor, much to the chagrin of his co-workers who are goaded by their supervisors to keep up. Piece work means they’re paid per item produced, but fined if they fall under quota, and because of Lulù, they’re made to look like lazy underperformers by comparison. One man sidles up to Lulú and tells him, “You won’t die in your bed, you’ll die here on your machine.” It also resonates with Patti Smith’s poem, written in the 1960s and used as lyrics for her milestone 1974 track “Piss Factory”—“You screwin’ up the quota, You doin’ your piece work too fast, You ain’t goin’ nowhere, you ain’t goin’ nowhere.”

Turns out they’re working eight-hour shifts, six days a week, for 50 weeks per year and the management can only offer them more hours to earn enough to cope with rampant inflation. Still sounds familiar, right? But what choice do they have?

Their newly formed union is negotiating a limited strike, but some workers demand more radical action. Outside the factory gates, protestors from the coalition of students and workers demand “more money, less work,” criticising the unions for serving the bosses when compromising to protect jobs. Friendless and ridiculed, Lulù just wants to be allowed to work, he knows little else and has the upkeep on the flat he shares with Lidia and her son, as well as alimony payments to his ex-wife and his own son. No way can he afford to lose pay through strike action. In the US, the film was released as Lulu the Tool because that’s what he feels he has become and how others may see him—just another component on the assembly line.

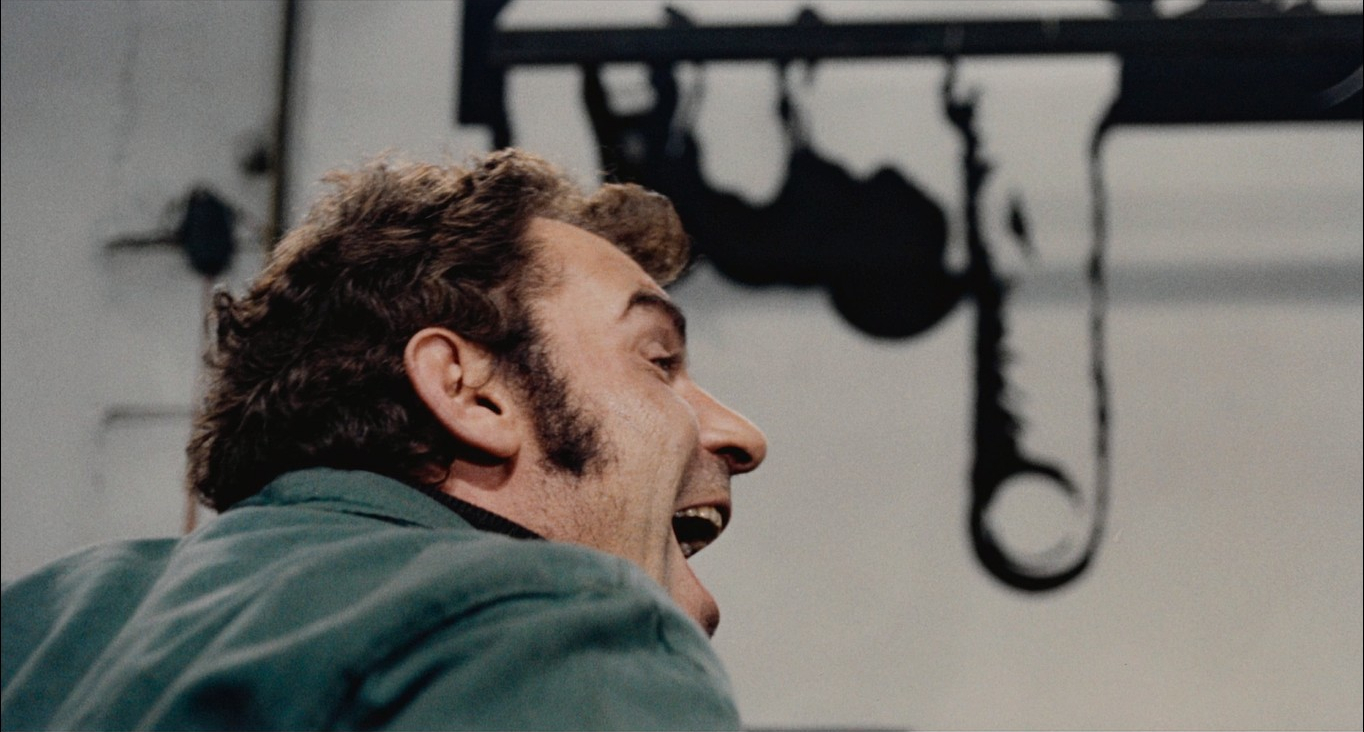

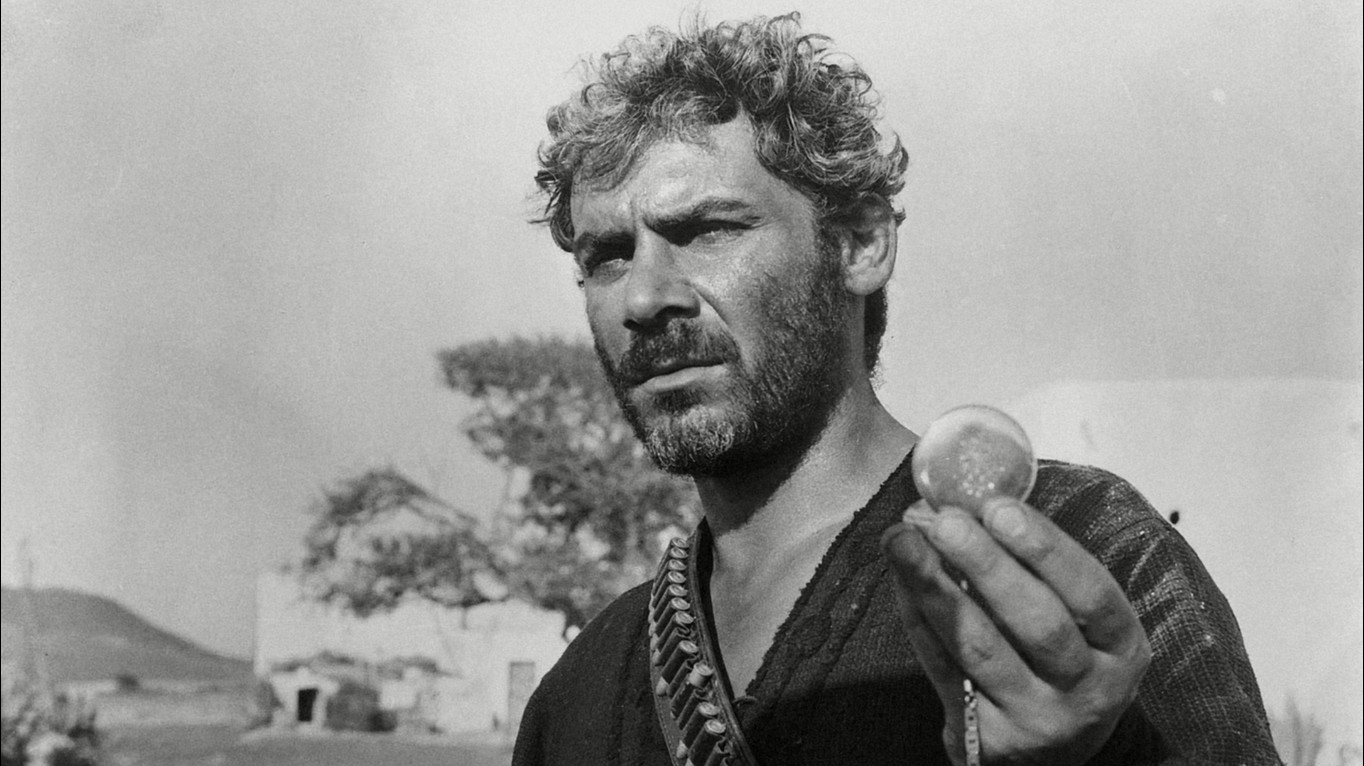

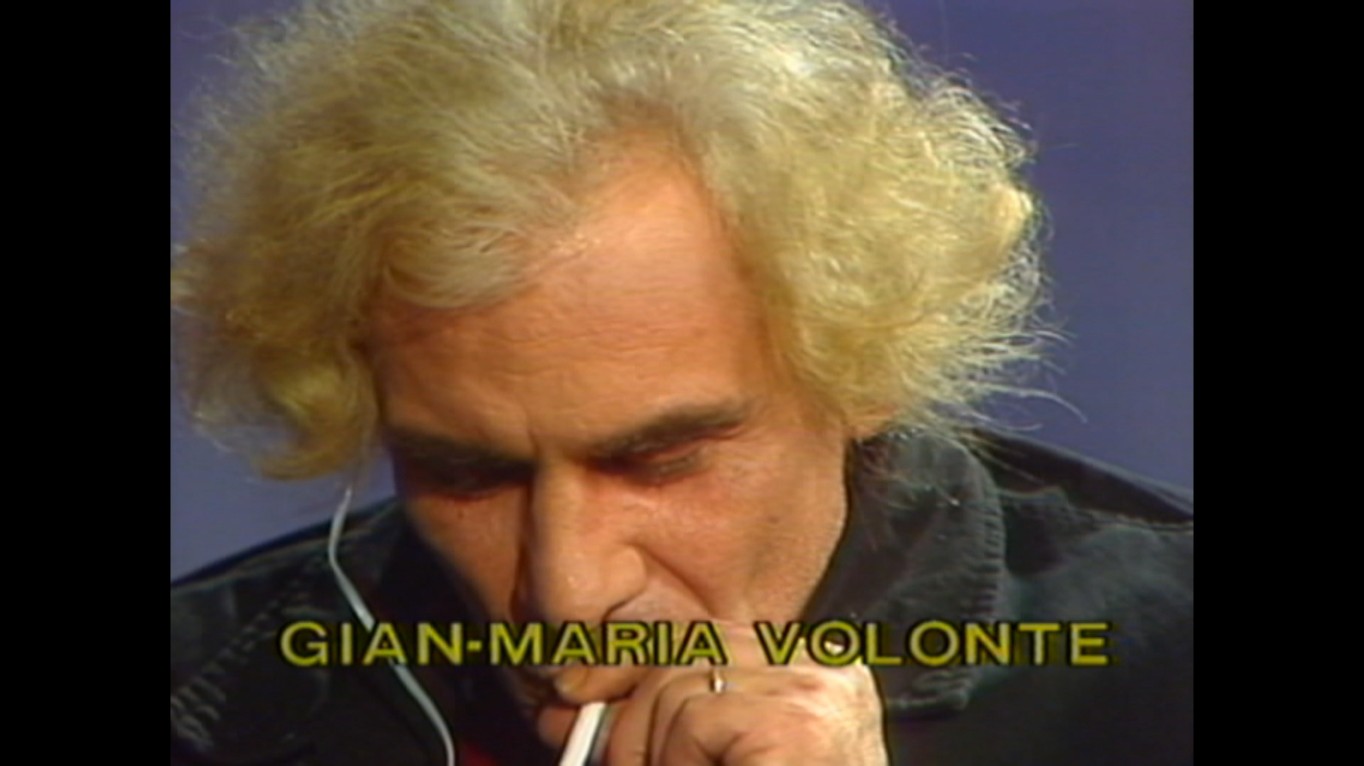

The central performance from Gian Maria Volonté is riveting throughout and is the essential component holding the entire film together. He plays Lulù as a brash, bullish, man-child going through a classic mid-life crisis. He’s sexist, abusive, unlikeable, and yet his barely concealed vulnerability elicits a degree of sympathy. He’s never been allowed to mature, having no real experiences outside the factory, and no opportunities for development, since starting the job as a teenager. He’s emotionally stunted and still a 15-year-old at heart.

He seems to have lost all hope of anything changing for the better since, years before, his older colleague and mentor attempted to organise the workers to strike for better conditions and was fired on grounds of insanity. Lulù still visits Militina or ‘The Militant’ (Salvo Randone) in the local madhouse and begins to fear for his own sanity as he recognises more and more of himself in his comrade. Veteran character actor, Salvo Randone will be familiar to any fans of Italian pulp cinema. I know him best for proto-giallo The Possessed (1965) and his previous work for Petri alongside Volonté in We Still Kill the Old Way (1967) and Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (1970).

Things abruptly change when Lulù’s distracted whilst operating his lathe and the machine jams. A moment’s lapse in concentration costs him a finger and, unintentionally, he becomes a symbol of the exploitation of workers, a catalyst for more militant action by the union. During assessment by the company psychologist, he begins to see that insanity could be a way out, a little like the ploy that backfires for Randle McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and, in some ways, the factory environment already feels like incarceration.

Spurred on by his colleagues and the indignity of his symbolic emasculation, he now becomes a willing activist and risks his own livelihood in the process. Lulù is totally believable, never approaching any romanticised notion of the working class and Volonté adds a depth of complexity to what a lesser actor may have turned into a caricature. Apparently, he worked at the Falconi factory in Novara for a whole month in preparation for the role. He clocked in and out like any employee, studying the dynamics of the workers and familiarising himself with the machinery so he could operate it as second nature. This sense of realism was extended when Elio Petri shot on location in the factory whilst it was occupied by the protesting workers, many of whom appear in the film as extras. Reputedly, some of the tussles between rival factions were genuine and unscripted.

This was at a time when student groups were occupying campuses, workers were striking, and protests spilt into the streets of major Italian cities, often leading to clashes between groups with opposing ideologies and sometimes in bloody violence when police stepped in to break up the demonstrations. Far-right extremists had already taken to acts of terrorism, such as the Piazza Fontana bombing of December 1969, heralding the so-called ‘Years of Lead’—an extended period of socio-political unrest and violence that would last 20 years, until the late-1980s. Petri’s preceding feature, the prescient Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, had also been set against this historical backdrop and starred Gian Maria Volonté in a very different role as a psychopathic police chief investigating political crimes and corruption in high office.

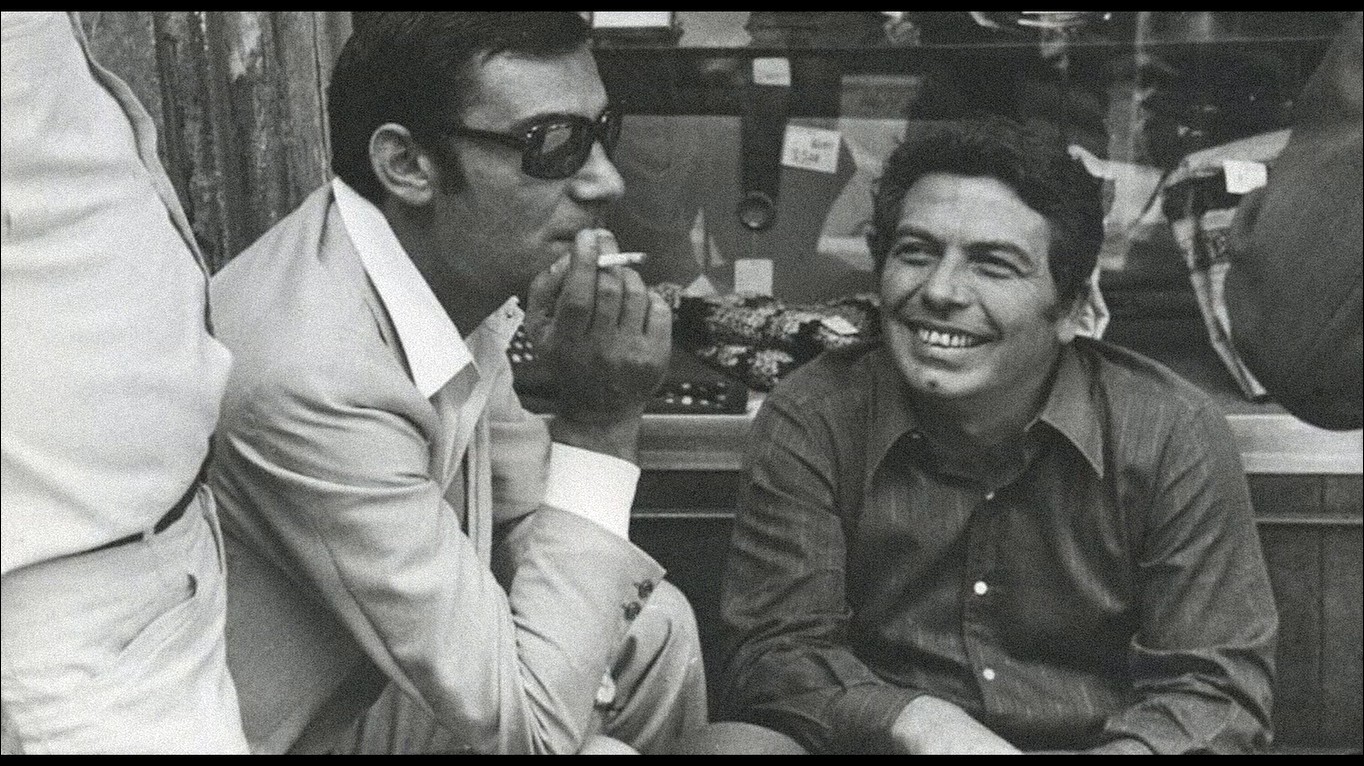

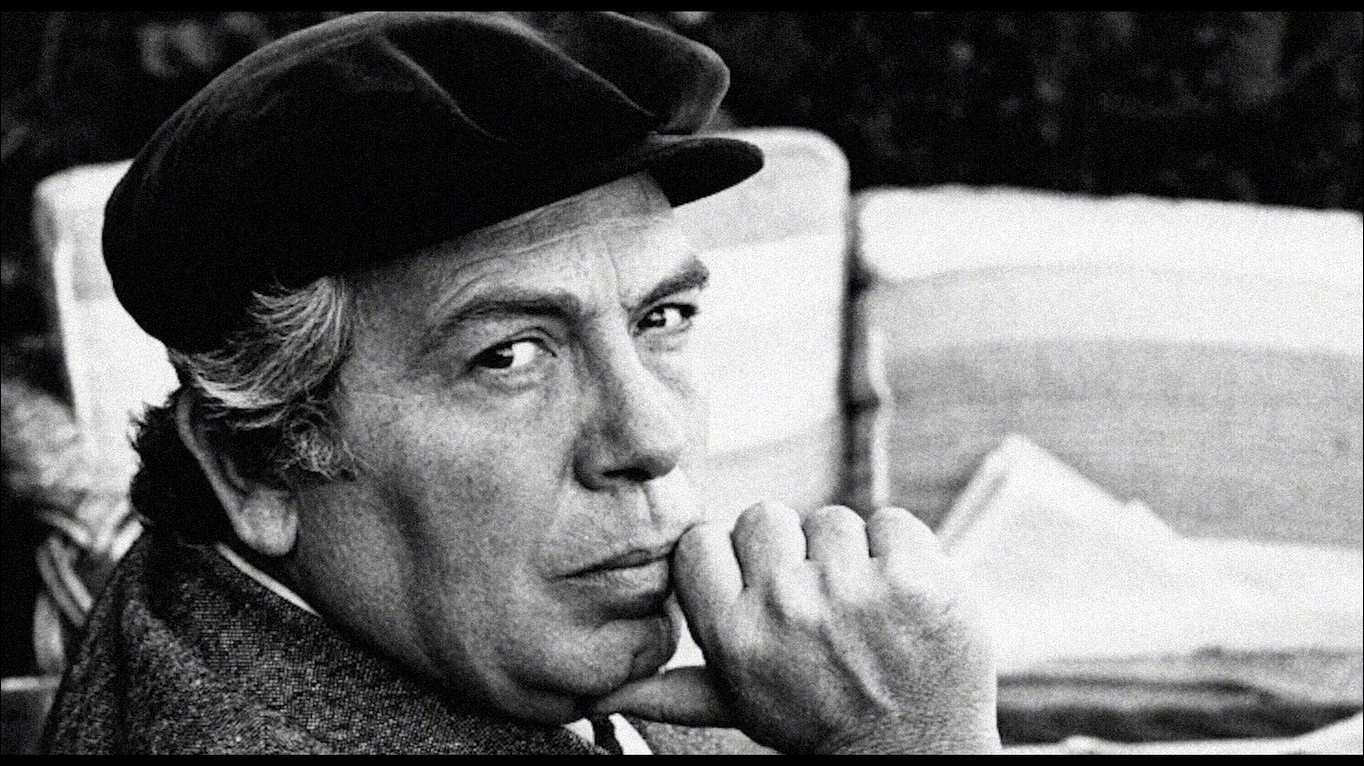

Petri and Volonté were repeat collaborators, they worked and played together, protested and got arrested together. Both had Communist leanings, Petri had started his career as a film critic for l’Unità, the official newspaper of the Italian Communist Party though he left the party in 1956 after the Hungarian Uprising when the schism between socialist Marxism and Stalinist totalitarianism widened. Together they made four socio-political films of which The Working Class Goes to Heaven may be the most complex and challenging in that it operates as more of an analysis and arbitration than a political polemic, offering a rough rapprochement between antagonistic ideologies.

However, it remains accessible to a wide audience and can also be viewed in a similar context to a kitchen sink drama akin to the British social realism of the 1950s, typified by films set against the working-class backdrop of England’s industrial North. Such as John Osborne’s 1956 play Look Back in Anger, which he adapted with the help of Nigel Kneale for the 1959 film starring Richard Burton, and Shelagh Delaney’s 1958 play A Taste of Honey which she adapted as the 1961 film starring Robert Stephens.

The Working Class Goes to Heaven has elements of gritty soap opera too, and upon release in the autumn of 1971 cinemas were packed with working-class audiences eager to see themselves represented and the film’s authenticity was well-received. It was also critically recognised and won the 1972 Grand Prix International du Festival (as the Palme d’Or was known then) at Cannes. It shared the award with Francesco Rosi’s The Mattei Affair (1972) which also starred Gian Maria Volonté thus winning the actor a ‘Special Mention’ award. Back home in Italy, it won the David di Donatello Award for ‘Best Film’ and Mariangela Melato was also singled out for a ‘Special Mention’. She also received the prestigious Nastro d’Argento / Silver Ribbon from the National Syndicate of Film Journalists, Italy’s longest-established film award, and a second was awarded to Salvo Randone for his vital cameo.

ITALY | 1971 | 115 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN

director: Elio Petri.

writers: Elio Petri & Ugo Pirro.

starring: Gian Maria Volonté, Mariangela Melato, Corrado Solari, Gino Pernice, Donato Castellaneta, Flavio Bucci, Carla Mancini, Salvo Randone.