BLIND BEAST (1969)

A blind sculpter and his mother kidnap a young model.

A blind sculpter and his mother kidnap a young model.

Generally, films described as character studies are slow and painterly dramas of the Manchester by the Sea (2016) variety: understated and respectable, light on action and heavy on introspection. Yasuzo Masumura’s Blind Beast, a chamber drama that exists somewhere at the tangled psychosexual intersection of Psycho (1960) and Dead Ringers (1988), isn’t that prestigious of a film. To call a movie this outlandishly charged with mommy issues Freudian would be doing it a disservice! If Sigmund Freud were alive to see it, he’d hardly make it past the opening credits before having a fatal heart attack. While it may lean a little more towards the Marquis de Sade than Vittorio de Sica, there’s no denying there’s a perverse strangeness at work here that remains mesmerising even when at its most repellent.

Masumura drops us into the deep end from the first frame, opening on black-and-white stills of our narrator, a young disaffected fashion model named Aki (Mako Midori), nude and bound by chains. Aki is supervising a gallery of the aforementioned portraits and sculptures modeled after her, and her only company in the gallery is a blind man (Eiji Funakoshi) obsessively caressing a statue’s breasts while murmuring to himself. For most people, this would sound the alarms for imminent danger, but she simply shrugs him off as an eccentric and continues. Not much time passes before she finds herself chloroformed by the man’s mother (Noriko Sengoku) and kidnapped away to his perpetually dark art studio literally filled to the ceiling with enormous stone statues of body parts and appendages. Love Actually (2003) this is not, and things only get more depraved from this point on.

The film seems half-interested in using these unsettling sculptures as a means of exploring the objectification of women and how society treats disability, but exploitation always takes priority over nuanced subtext. Shortly after the pivotal kidnapping, the blind artist, whom we soon learn is named Michio and who lives in the studio with his slightly overbearing mother, gives a very “whoah, that’s deep…” speech about the five senses and what physical surfaces he as a blind man enjoys touching most, but the self-consciously disturbed monologues always come off sounding ridiculous to some degree. Edogawa Rampo, who wrote the short story that inspired the film, is often referred to as the Japanese Edgar Allen Poe, but he wasn’t nearly as interested in Poe’s slow-burn Gothic elegance or restraint. His stories, and by extension this film, are much more in the vein of grand guignol spectacle and shock value than in literary suspense. Masumura maintains a good enough poker face in directing the film that it’s never completely clear how we’re supposed to be reacting to the ever-escalating excess of the plot, but it’s safe to assume there’s a certain level of tongue-in-cheek provocation at play. It’s got The Human Centipede (2009) syndrome—you’d get plenty of odd looks for calling it a funny movie, per se, but if you take it completely at face value you’re missing the point a little.

The Human Centipede comparison suggests this is some kind of gritty splatter film, like Saw (2004), but if anything it’s more aligned with the disorienting experimentalism of the Japanese New Wave, and can stake a claim to being one of maybe only four or five horror films of the movement. As is par for the course for those films, Blind Beast seems to exist in a jagged, funhouse mirror world with claustrophobic camera angles and abrupt cuts that distance it, if not sever the connection altogether, from the understated social realism of earlier Japanese masters like Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. If anything, it’s stylistically and tonally in line with the anxious existential fables of fellow new wave filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara. In fact, the plot’s remarkably similar to Teshigahara’s film The Woman in the Dunes (1964), right down to the finer nuances of the character relationships, albeit if the “woman” of the title were a blind and horny psychopath and the “dunes” were made of massive breast and eyeball sculptures. Even if Masumura approaches the story from a sleazier, more grotesque angle, his film has the same sense of unease and visual grandiosity that elevates it to something slightly more substantial than your average exploitation affair

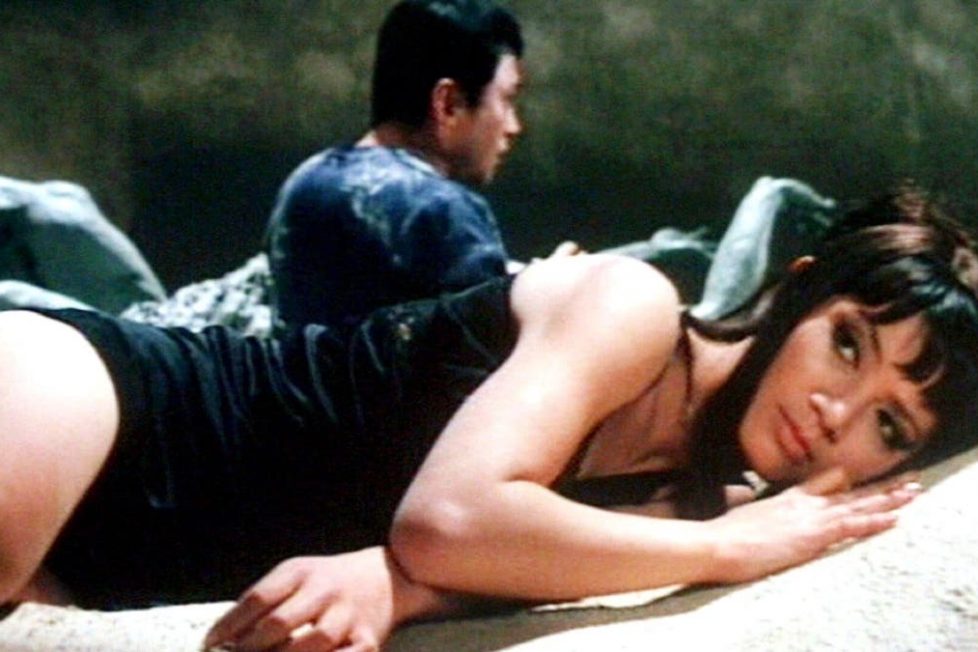

Along the same lines, the plot’s really only a small part of the appeal of the film. Much more fascinating are the completely alien, Salvador Dali-esque sets and the equally bizarre sound design to match it. In Michio’s studio, the three characters are constantly climbing and writhing against sculptures that may as well be physically manifested misogyny while set against complete blackness. Michio and Aki wrestle on gigantic breasts and hang off a wall of ears, all while distant clanging and echoes sound off behind them as if they were in outer space rather than an art studio off the beaten path. The room might as well be another planet—the three characters are always shown in a dark void, with only the dimmest expressionistic lighting illuminating their surroundings. Crude as this may be on the surface—and things get very crude by the finale—there’s a disorienting artistry to the production design that keeps the film looking far from cheap or rough. Perhaps it’s ultimately too repulsive for most viewers even with that high-art sheen to it, but stories of artistic obsession and sexual violence rarely cut as deep as this.

JAPAN | 1969 | 86 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Yasuzo Masumura.

writer: Yoshio Shirasoka (based on the novel ‘Moju’ by Rampo Edogawa).

starring: Eiji Funakoshi, Mako Midori & Noriko Sengoku.