BILLY ELLIOT (2000)

A talented young boy becomes torn between his unexpected love of dance and the disintegration of his family.

A talented young boy becomes torn between his unexpected love of dance and the disintegration of his family.

Superficially, Stephen Daldry’s Billy Elliot stands in the grand tradition of works that wallow in misery to make us feel good, running from Oliver Twist to Angela’s Ashes and beyond. It could easily have been a piece of maudlin emotional exploitation. And it comes close occasionally, notably when a dead mother’s prized piano is smashed up for firewood to provide a little heat at Christmas.

But Billy Elliot never once tips over that brink, thanks not only to Lee Hall’s razor-sharp script (adapting his own play Dancer) and Daldry’s direction but also the performances of the four main actors, all of whom invest their characters with depth and humanity that’s often just glimpsed on-screen rather than wheeled out for all to weep over.

The story takes place across a few months in 1984-85 in County Durham, England, in a bleak and impoverished town riven by the bitter miners’ strike where the unions confronted Margaret Thatcher. Given this is now receding rapidly into history, it makes Billy Elliot (despite being made more than a decade later) an interesting quasi-documentation of a specific place and period too.

11-year-old Billy (Jamie Bell) lives with his miner father Jackie (Gary Lewis) and older brother Tony (Jamie Draven), as well as their elderly grandmother. The boys’ mother is dead. Billy seems an average kid, keen on the boxing lessons his father’s arranged for him, although perhaps not as talented at the sport as he claims. He discovers a new interest, though, by watching the ballet classes conducted in the boxing hall by Sandra (Julie Walters).

Before long he’s dropped boxing for ballet, unbeknownst to his father, who is horrified when he finds out. Ballet, after all, is for girls and “poofs”, but Sandra’s adamant Billy has the potential to dance professionally and encourages him to audition for an important London ballet school.

The ideas that this situation throws up are on clear display. There’s the foremost issue of maleness (boxing is macho and heterosexual, ballet isn’t), and that’s not only the unreconstructed view of Billy’s father. Billy himself tells Sandra that “I feel like a right sissy” for dancing. Billy’s own sexuality is never explored, but it’s surely significant that his best friend Michael (Stuart Wells) is clearly gay. Even if Billy isn’t, he might as well be from the perspective of his community. An obvious comparison is made between Michael’s and Billy’s separate paths to self-realisation, too.

Set alongside this, there’s also the permeating feeling of a society about to disappear. The miners will, before long, accept defeat and the old smokestack Britain represented by Jackie (and, literally, by the huge chimneys behind the graveyard where Billy’s mother is buried) will start to give way to a service economy in which cultural industries, like ballet, are more valued than digging coal. None of the characters knows this, of course, but they can surely sense it.

Insofar as it takes sides, Billy Elliot’s sympathies are clearly with the miners. In one scene, cutting between a ballet class and a confrontation between strikers and the police, Sandra is imploring her young dancers to be “powerful! proud!” just as we see Billy’s father on the picket line. The only slightly disagreeable character, Sandra’s husband Tom (Colin Maclachlan), is also the only one to defend the government’s side; and even the principal of the ballet school where Billy eventually auditions (an amusing cameo by Patrick Malahide) wishes Jackie good luck with the strike, doubtless the filmmakers’ little dig at well-meaning southern liberals…

However, while all this provides texture and a grounding in reality for the film (so that despite its flights of fancy and departures from a conventional narrative, it never feels like pure fantasy), Billy Elliot is far from preoccupied with its social context. Fundamentally, it’s all about the people, the music, and the dancing.

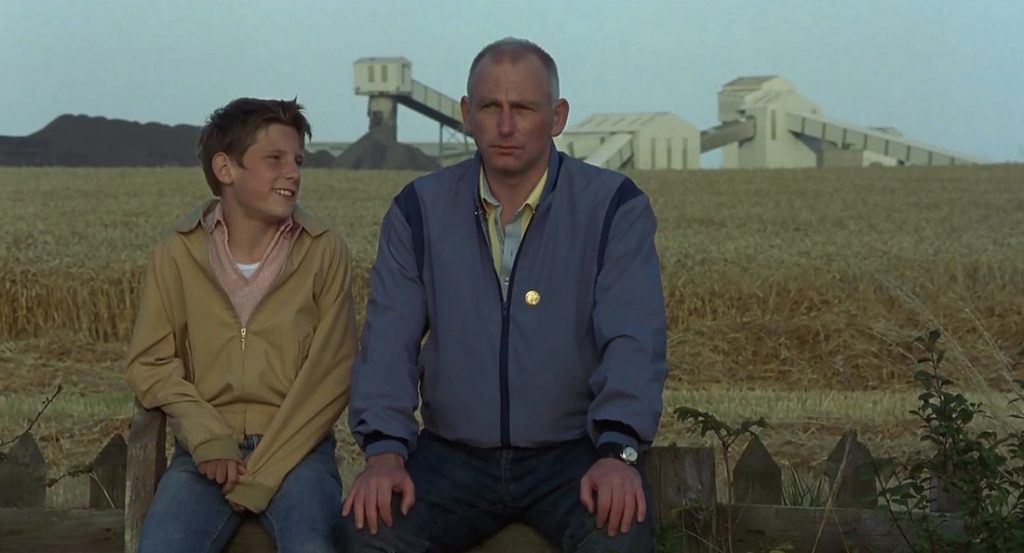

The outstanding performances come from Bell as Billy and Lewis as his father. Indeed, to some degree the movie is about the older man as much as the young boy. Lewis is superb and tightly coiled with anger at the world and the way it’s let him down, rather than anyone or anything in particular. His pain at being forced by circumstances into crossing the picket lines is palpable, and his slow acceptance of Billy’s dancing future is tinged with reluctance. As they walk together to catch the coach to London and Billy’s audition, the boy is dancing down the street and Jackie asks “is that absolutely necessary? Walk normal, will you?”

But the vulnerabilities in Jackie are gradually exposed, too. For example, in his argumentative relationship with his older son. Even the tiny moment where he fiddles with an ornate wrought-iron balustrade in the grand building where Billy’s audition is taking place (actually New Wardour Castle in Wiltshire) speaks volumes. We realise Jackie has never encountered anything like this before.

Bell, only 13 when the film was made, offers many hints that Billy is his father’s son as well as a potentially brilliant artist, and indeed it’s crucial to the dramatic success of Billy Elliot that the character is not unequivocally committed to dance, mature beyond his years, or sophisticated beyond the limitations of his upbringing. His face is an expressive marvel, but it is dominated by doubt and wariness with only occasional bouts of joy; we witness his temper, too.

Elsewhere in the cast, Draven bridges the gap between Lewis and Bell in his portrayal of a young man further along the road to becoming his father. When Billy receives a letter from the ballet school after his audition, we can see on their faces that both brother and dad are expecting disappointment as this is their norm. Walters, as the chain-smoking ballet teacher, is closer to stereotype than any of the others, but she never overdoes the part and is particularly good in a two-hander inside her car where the possibility of Billy going to ballet school in London is first mentioned.

And then there’s the dance, so integral to Billy Elliot but so often in a non-diegetic way. There is, in fact, comparatively little dancing in the story as such. But we see Billy’s legs before we see his face (just as the camera will later tease us by delaying the moment that we first see him in a ballet class), and his reactions to developments in the realistic narrative are often expressed in dance that breaks out of it.

In the movie’s most famous and exultant scene, for example, Billy is seen tap-dancing down a lane between red-brick walls until he bumps into a sheet of rusty corrugated iron that blocks his way (rather blatantly representing his decaying industrial society). Then, despite the bright weather during most of this sequence, there’s suddenly snow on the ground and we understand that months have passed and winter has arrived.

That’s only one example of the way that Billy Elliot’s dance scenes often slip out of kitchen-sink realism. More potent, indeed, is the scene where Jackie confronts Billy at the boxing club one night and Billy, instead of replying, simply starts to dance… both trying to show his father how much he revels in it and perhaps standing up to him too.

Other dance sequences range from the overtly unreal (notably one which cuts between Billy dancing, his grandma doing the same, his father gargling and his brother pretending to play the guitar, all to T. Rex’s “I Love to Boogie”), to those which aren’t strictly dance but nevertheless make their point through physical movement. For example, Billy pounding the air in a rage after an argument with his dad.

Backing up all this is a perfectly-selected soundtrack, with T. Rex looming large (“Children of the Revolution” is a highlight, and indeed the first shot shows Billy putting on a record of Cosmic Dancer) alongside darker numbers like The Clash’s “London Calling” and The Jam’s “Town Called Malice”. Tchaikovsky’s music for Swan Lake is pointedly used as the background to the one main scene set by the water, a decidedly non-romantic dock.

Cinematographer Brian Tufano keeps things moving without distracting from the characters or the action. There are some bold images, but the visual accent for most of the movie is firmly on Billy himself, with plenty of motion to help ensure that although the main plot of Billy Elliot progresses relatively slowly, the film never drags. To the same end, there’s plenty of physical humour—especially in Billy’s dance practice at home, and his look when Michael opens the door wearing a dress is priceless.

Billy Elliot was made by a team with more theatrical than screen experience. Hall had done only a little TV writing, and it was Daldry’s first feature, although his career as a stage director had been eminent. Before Billy, he’d been artistic director of the Royal Court Theatre in London for six years. Yet it never feels limited by a proscenium arch, even if its limited number of locations must have been welcome to Hall when he went on to write a 2005 stage version and, indeed, both men used it as the launchpad for successful screen careers. Daldry most notably made The Hours (2002) and then the Netflix series The Crown, while Hall’s work including Rocketman (2019) and, to less acclaim, Cats (2019).

Bell became a consistently well-regarded presence on screen (even if never a major star), with recent work including Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool (2017) and a notable part in Rocketman, as well as the lead in the lengthy AMC series Turn: Washington’s Spies. Walters, unlike anyone else in the Billy Elliot cast, had been a big name since Educating Rita (1983) and continues to be one. Lewis also continues to be active on camera, mostly in character roles.

Billy Elliot was nominated for three Academy Awards (‘Best Screenplay’, ‘Best Director’, and ‘Best Supporting Actress’ for Walters. And although it won none of its categories, the BAFTAs more than made up for that, with success in the ‘Best Film’, ‘Best Actor’ for Bell, and ‘Best Supporting Actress’ for Walters, as well as nine other nominations.

Box-office returns were healthy considering its low $5M budget, although Billy Elliot’s principally British appeal prevented it from becoming a major hit internationally. Critical reception was almost uniformly excellent, with The Guardian’s Peter Bradshaw described it as “a film with a lot of charm, a lot of humour and a lot of heart”, as well as “a freshness that makes it a pleasure to watch”.

Indeed, that freshness may be the single most striking thing about Billy Elliot today. The film is set nearly 40 years ago, and most of the details of a real Billy’s life would be vastly different today. (He would be much less naive, for sure.) But it never feels like a period piece because there are two intertwined stories that don’t age at its core: a boy figuring out his place in the world, and a boy and his father figuring out their relationship.

The genius of Billy Elliot is that it’s presented in such a relaxed and unpretentious way and performed so convincingly, that it achieves that perfect balance between entertainment value and emotional honesty. It feels good, but it’s not just feelgood.

UK • FRANCE | 2000 | 110 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Stephen Daldry.

writer: Lee Hall.

starring: Julie Walters, Gary Lewis, Jamie Bell, Jamie Draven & Adam Cooper.