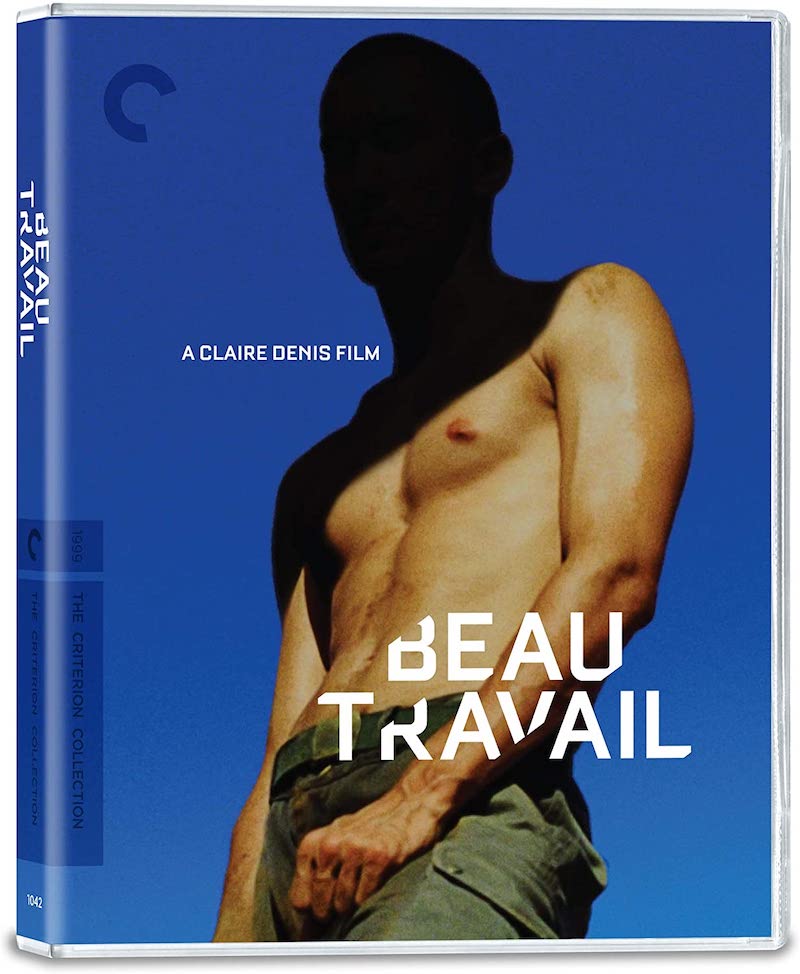

BEAU TRAVAIL (1999)

An ex-Foreign Legion officer recalls his once glorious life, leading troops in Djibouti.

An ex-Foreign Legion officer recalls his once glorious life, leading troops in Djibouti.

Claire Denis’s Beau Travail is a film of contradictions: it’s a military movie in which there’s no war or a clear purpose for its soldiers, a drama about the ugliest of emotions (resentment, jealousy, self-hate) which is nonetheless sensuously gorgeous, and a film of seemingly big events (a helicopter crash, an attempted murder, a court-martial) where little seems to happen.

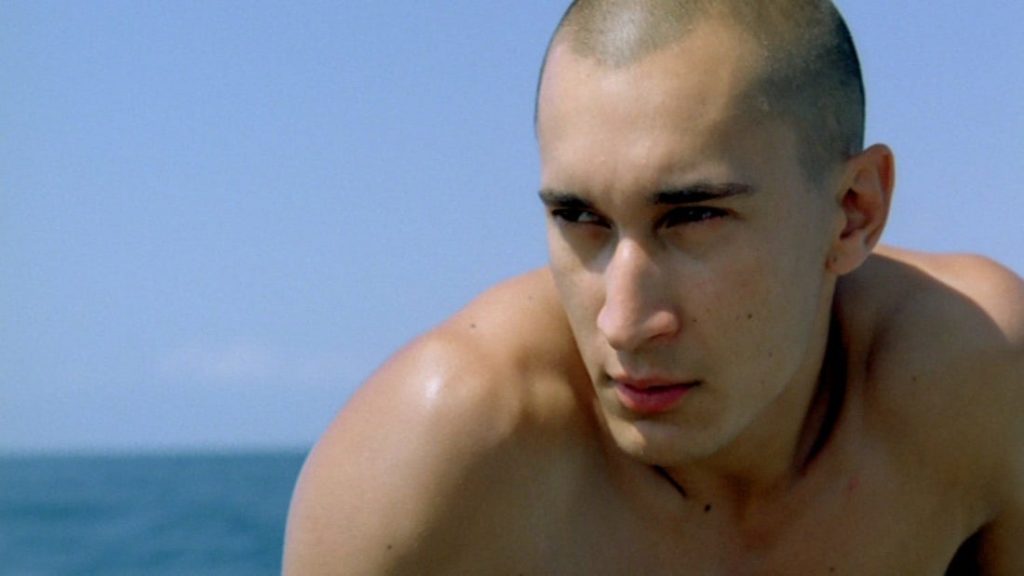

Judith Mayne, in her discussion of Beau Travail (which is the best extra on Criterion’s new Blu-ray), sums it up as “ethereal and concrete at the same time.” It’s full of physical activity, yet in tenor, it’s overwhelmingly concerned with the inner life rather than the outer. (In this it sometimes recalls Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line, from a year earlier.) Its characters, most of them unnamed and given scant dialogue, often don’t feel quite real; more like ghosts or memories, existing out of time. And we’re never entirely sure if we’re watching the recollections of Sgt Galoup (Lavant), the central figure, or his fantasies, or an objective record of what happened to him and the men under his command at a sun-baked French Foreign Legion outpost in Djibouti.

Unsurprisingly, then, Beau Travail—while universally highly acclaimed, and achieving a place in Sight & Sound’s list of the 100 Greatest Films of All Tie—often acts as a kind of Rorschach test for critics, who can see in it their own preoccupations.

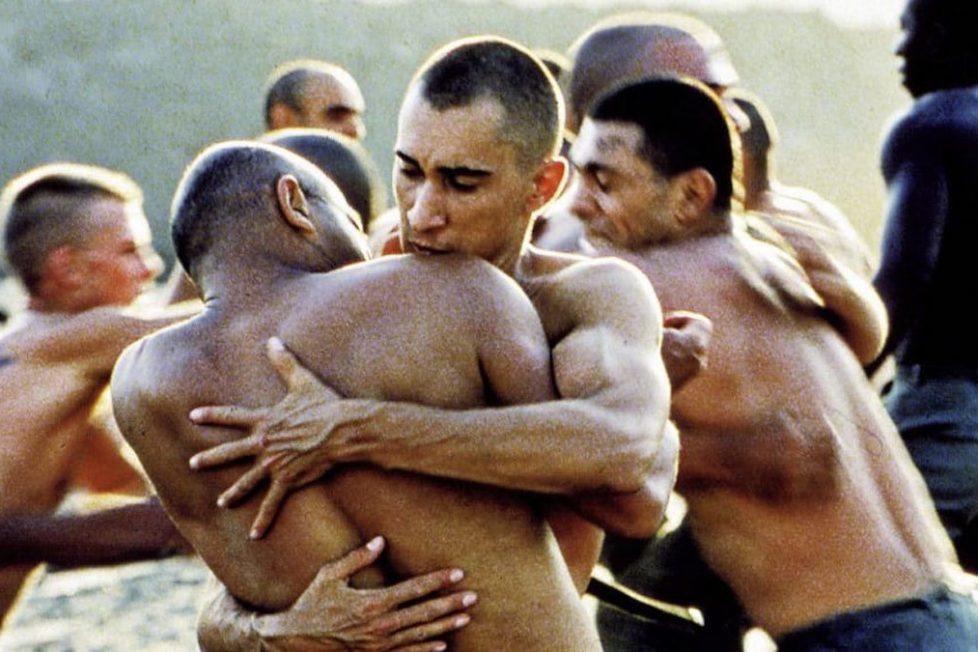

It’s been interpreted as a commentary on post-colonialism. Although its African location may seem only incidental, many of Denis’s films are set on the continent, and while cultural tensions are not central to Beau Travail, they’re not ignored either. Others see it as portraying the way the military suppresses individuality. And unsurprisingly—given its virtually all-male milieu and the ceaseless parade of tanned, toned young soldiers–many have detected a gay dimension. (This undoubtedly is present, to an extent, although it’s worth bearing in mind the director and cinematographer are both female, so maybe it says something about male-dominated interpretations of film that we assume aesthetic attention to male bodies must itself come from a male perspective?)

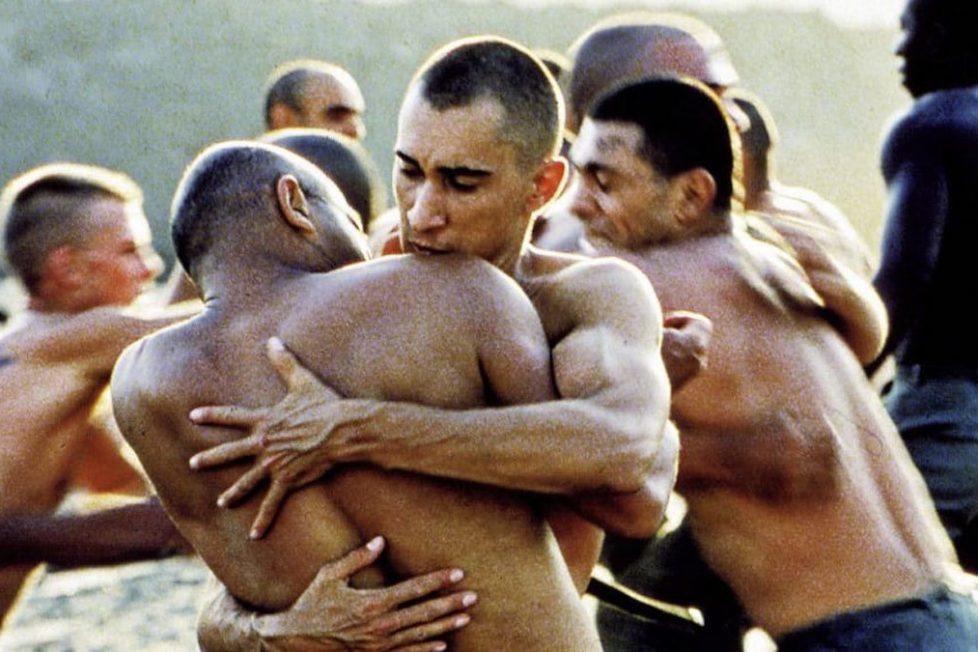

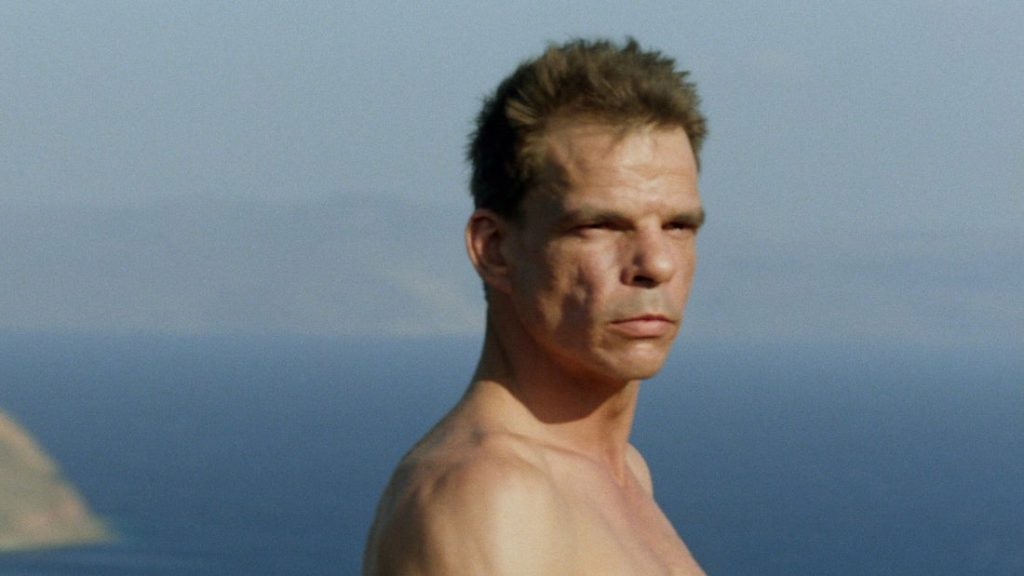

This elliptical, dreamlike movie is perhaps what you want it to be. But a certain amount is clearcut. A group of about 20 French Foreign Legionnaires are stationed in east Africa and led by Sgt Galoup, who has a friendly relationship with his superior, Major Forestier (Michel Subor). Soon a new member joins the squad, 22-year-old Gilles Sentain (Grégoire Colin), a handsome, friendly, popular, good soldier, who seems to attract the approval of Forestier…

Galoup grows jealous (“I felt something vague and menacing take hold of me” almost as soon as Sentain arrived, he recalls), and this is where the film grows complex: who or what exactly is he jealous of? Does he, a slightly squat and rough-hewn man whose youth is now behind him, simply envy Sentain’s apparent perfection? Or does he resent the way that Sentain is becoming Forestier’s favourite when, previously, Galoup was the only man in the unit close to the major?

Is there, indeed, a sexual element to the tension? There’s a fleeting but unmistakable hint one night that Forestier is making a pass at Sentain, and there are indications elsewhere that Galoup’s own heterosexuality might be a charade. His supposed relationship with a young local woman, Rahel (Marta Tafesse Kassa), seems far less important to him than the presence of Sentain, and it’s not difficult to imagine that Galoup’s smouldering anger at Sentain is a result of the younger man forcing Galoup’s deeply repressed feelings to the surface.

In any case, whatever the source of his annoyance, Galoup becomes steadily more obsessed. He falls into slovenliness and his reactions become extreme; at one point he appears to punish another young Legionnaire simply for being pals with Sentain. There’s a sense of mounting dread as the unit’s activities, always imbued with an air of strangeness, seem to become even less like real military training and more like a ritual, even ballet. This leads to the film’s climactic events, which in turn leads to Galoup’s expulsion from the Legion. (This isn’t a spoiler because from early on we’ve seen him looking back from his new civilian life, performing dreary household tasks in his tiny Marseille apartment.)

All the while, remarkably, Sentain has remained absolutely inscrutable. He barely says a word. In fact, both he and Major Forestier are blanks. The same is true of the rest of the Legionnaires. Even though the different ways they perform the same training tasks indicate there are still individuals beneath the automatons, we learn hardly anything of them, their thoughts or their backgrounds. (Where Forestier is concerned, though, cineastes may make some deductions about the major from the fact that the same actor plays a character of the same name in Jean-Luc Godard’s 1963 Algerian-set Le Petit Soldat, lines from which are also used in Beau Travail).

Instead, everything is told from Galoup’s point of view, with his narration giving ample expression of his inner thoughts.

Or so it seems. Yet there are scenes where Galoup isn’t present. So, in them, are we simply seeing what he imagines to have happened? Denis and her regular writing partner Jean-Pol Fargeau never make it clear in the screenplay or, indeed, spell out much about the meaning we’re supposed to take from the film, although there are occasional indications from Galoup’s narration of the direction we should be thinking in. “We all have a trash can deep within”, for example—in which case what is his, what is Forestier’s, and most intriguingly what is Sentain’s?

This puts a huge burden on Lavant’s performance, and he’s compelling for every second of it, effectively exploiting (without overstating) the contrasts between the later, more ruminative Galoup in Marseille (thinking “I’m sorry that I was that man, that narrow-minded Legionnaire”) and the driven, raging Galoup of the Djibouti flashback scenes. In both timelines he makes the most of the character’s military background, generating tension from the contradictions between his self-contained soldierly bearing and the all-too-expressive face. And he’s also magnificent in the strange and famous final sequence where Galoup dances, alone and ungainly, in a deserted club to Corona’s “Rhythm of the Night”.

For all that, Beau Travail is still very much a director’s and cinematographer’s film. Denis (possibly still best-known for her debut 2000 feature Chocolat) and Agnès Godard command our attention in purely cinematic ways, quite independent of the drama. This emphasis on the visual is evident right from the opening shot (a mural apparently depicting soldiers on a landscape, colourful and redolent of Africa) and throughout, the drama is often paused to maximise the atmospheric value. One particularly breathtaking early shot slowly traces the shadows of Legionnaires across the baked earth before revealing the bodies they belong to. Later, another depicts the men as tiny pink figures on a vast canvas of rocks, sea, cliff, and sky… their different shades arranged in layers. What the men are doing is far less important than how small they are.

The landscapes of Djibouti’s Ghoubbet al-Kharab area lend themselves to this kind of composition, but in Godard and Denis’s hands, even the more tightly-framed, movement-filled sequences can be powerful mostly for the way they are shown rather than for what is shown. For example, when we see the Legionnaires on a training exercise crawling under barbed wire, looking like crabs. The aural isn’t ignored, either: the crunch of a woman’s feet on a desert salt pan is another moment that revels in the physical.

The title of Beau Travail clearly echoes P.C Wren’s Foreign Legion novels of the 1920s (the most famous of which is Beau Geste, itself filmed several times). But, insofar as there existing a literary source for Denis’s film, it’s Melville’s Billy Budd; a tale of envy and insubordination on the high seas amongst a male military milieu. Budd is roughly equivalent to Beau Travail’s Sentain while the novel’s Claggart is the counterpart of Galoup. The connection is made explicit by the use at several points in Beau Travail of music from Benjamin Britten’s opera of Billy Budd. Its seeming inappropriateness to a tale of Frenchmen in the desert adding yet another dimension to the film’s strangeness, it is complemented by an understated original score from Charles Henri de Pierrefeu.

But these connections shouldn’t be taken too literally. The biggest resemblance of Beau Travail to Billy Budd may be the ambiguity that both share, something that permeates almost every aspect of the film from the title itself (what work, whose, is “good”?) to Sentain’s impassive expression and Galoup’s inexplicable fixation. Reading too much into Beau Travail is futile: the beauty of this haunting, immersive work is that you are not always quite sure what you have seen, but tantalisingly certain that something profound has been happening just beyond the grasp of understanding, something that if only you could figure it out would finally make sense of everything else.

And if that’s a bit like life itself, maybe that’s the point.

FRANCE | 1999 | 90 MINUTES | 1.66:1 | COLOUR | FRENCH • ITALIAN • RUSSIAN

Wisely in this connection, Criterion’s extras add many new dimensions to the film without attempting to over-explain it; the highlights are the interview with Lavant and the video essay by Judith Mayne, while the 4K digital restoration (supervised by Godard) offers stunning colour and detail that’s perfectly suited to the crystal-clear photographic style of Beau Travail.

director: Claire Denis.

writers: Claire Denis & Jean-Pol Fargeau (based on ‘Billy Budd’ by Herman Meville).

starring: Denis Lavant, Michel Subor, Grégoire Colin, Richard Courcet & Nicolas Duvauchelle.