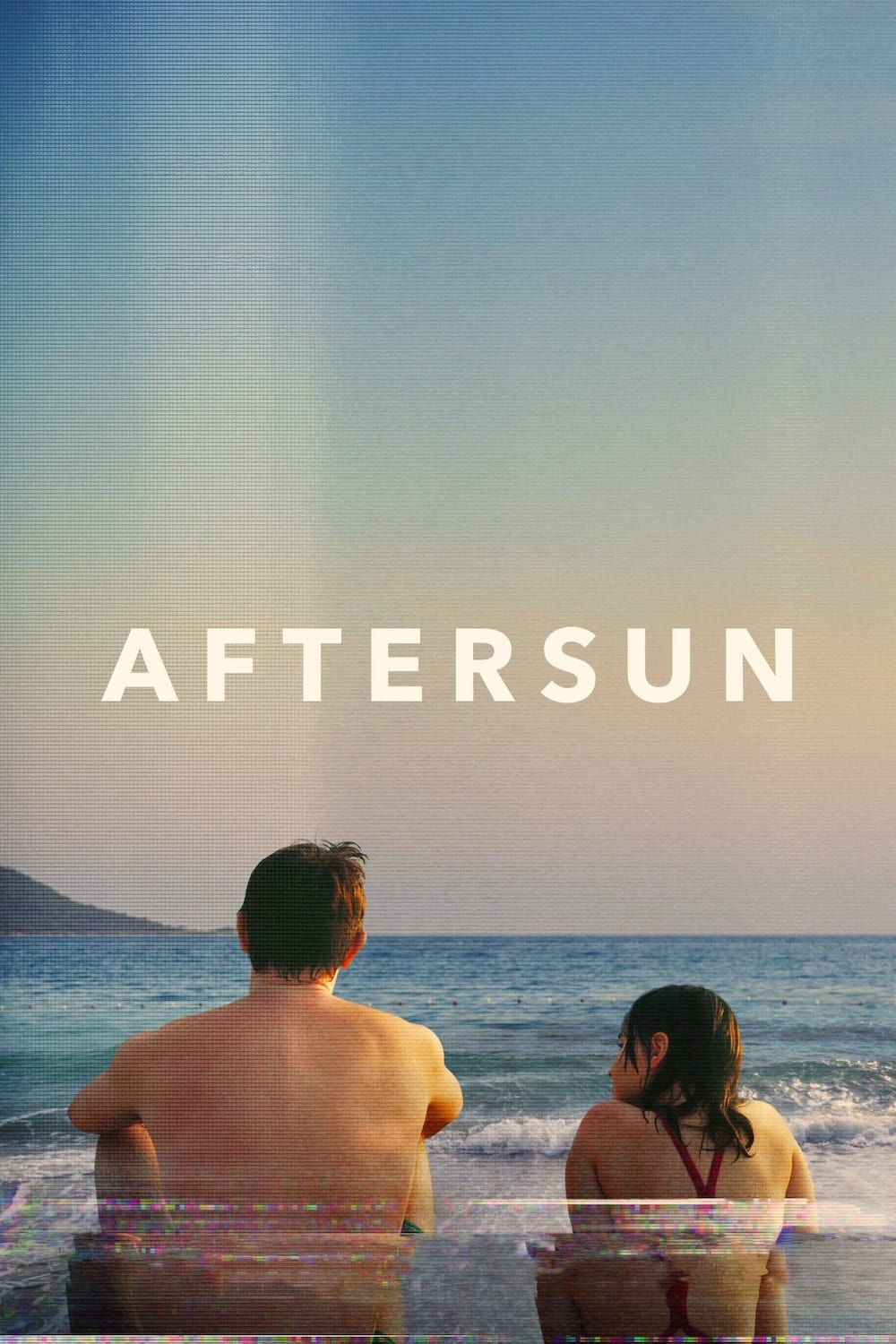

AFTERSUN (2022)

Sophie reflects on the shared joy and private melancholy of a 20-year-old holiday she took with her father, trying to reconcile the parent she knew with the man she didn't.

Sophie reflects on the shared joy and private melancholy of a 20-year-old holiday she took with her father, trying to reconcile the parent she knew with the man she didn't.

Give an example of a film that delves deep into parent-child relationships and it’ll likely be a character study at its core; one that leaves no stone unturned as both sides’ psychological profiles are unveiled to the world. Whether it’s Terrence Malick’s meditatively existential The Tree of Life (2011), Xavier Dolan’s searingly intense Mommy (2014), Greta Gerwig’s charmingly emotional Lady Bird (2017), or something else entirely, significant merit is attributed to films that understand the most productive relationships we’re likely to experience. Everyone is an inextricable part of their parents’ lives and vice versa, but just as people mature into their own selves—layered with rich internal lives, distinct personality traits, and unique wounds—so, too, have our parents from their childhoods, a concept these films explore with potent and elaborate detail.

However, a limitation that often goes unexplored is the indecipherability of other people: the fact that, no matter how close one grows to someone else, there will always be a part of who they are and what they’ve been through they’ve never shown to anyone. And it’s here that Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun—an astonishing feature debut whose calming, unassuming silence betrays a lifetime of maturity and wisdom—enters the equation, made with such subtle attention to detail and emotion that one would almost swear it’s a work from a longtime veteran. A meditative bildungsroman that mulls over the gaps in the memories of a father-daughter vacation to Turkey, Aftersun’s power lingers in how it peels open our inability to fully understand our loved ones’ most painful sorrows, and how that speaks more to our humanity rather than our fallibility.

Stitching together 35mm-shot vignettes from the past and low-resolution VCR footage, Wells creates a tapestry from these distinct mediums, images, and continuities that serve to impress the elusiveness of memory on her audience. The foundations of Aftersun‘s plot are relatively barebones and of little apparent consequence: Calum (Paul Mescal) and Sophie (Frankie Corio) are headed on a brief vacation to a Turkish resort in the 1990s to celebrate the latter’s 11th birthday, and the time they spend together slowly reveals more about themselves and their relationship. What appears to be a relatively minor vacation eventually grows into an event of great personal significance because of two major details: Sophie’s parents weren’t together, meaning this was one of the few instances she could see her father, and an adult Sophie (Celia Rowlson-Hall), several decades later, is obsessively reflecting over this particular vacation by constantly rewinding through VCR footage she took during it—all but saying out loud that she and her father likely never saw each other again afterwards.

It’s from that realisation onward that Aftersun becomes a remarkably controlled use of perspective as a means of narrative immersion; a film that puts you in the same emotional situation as Sophie, parsing through the gently depicted details of this vacation as we glean more details about her younger self and Calum, all of which are loosely put together to create a more complete portrait of a father unknown, and a daughter trying as much as she can to make him known. Whether it be through his more spontaneous exploits over the course of the vacation, or through the moments of bonding that he and Sophie share, every little piece shown contributes to this growing yet incomplete look at someone whose complex interiority could never have been fully explored.

One can’t help but notice the tai chi that Calum practices distantly and slowly, which Sophie describes as his “slow-motion ninja moves”; the cast on an arm he seemingly doesn’t remember breaking; the way he guides Sophie through an impromptu safety lesson about breaking free from a stronger assailant (one that she doesn’t seem to be taking all that seriously); and more pivotally, a modestly melancholy anecdote he shares with Sophie about his 11th birthday that he doesn’t let Sophie record on her VCR camera. But the moments where he truly reveals himself are few and far between—the layers behind the piecemeal, smaller things he does are ultimately what Sophie and the audience end up glimpsing and grasping at in what amount to only brief instances that fade in and out in the same breath.

At the same time, the limited array of information we find out about Calum overlaps with the way that Sophie’s maturity gradually unfolds over the course of this vacation, one that shows more about her curiosity in adolescent and adult affairs while refusing to necessarily culminate in a cathartic, affirming moment of growth. Much like how what we learn about Calum is through piecemeal bits of information, Sophie’s indulgence in maturity is only hinted at here and there: how she overhears a discussion about sex in the women’s bathroom, how she glances at the tourist teenagers also on vacation who more freely spout profanities and engage in intimacy, and how she gazes at a gay couple kissing in a bar from a distance. It’s just that for Sophie, one still gets to see the end result of these developments more concretely in what’s shown of her several decades later—the fact Calum still remains absent in the present day robs both her and the audience of the opportunity to really learn what the details we glean from him ultimately amounted to.

Worth mentioning here is that Aftersun also appears to be a semi-autobiographical work, a tradition frequently indulged by maverick filmmakers for many late-2022 releases such as Steven Spielberg’s The Fabelmans, James Gray’s Armageddon Time, even Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Bardo, False Chronicle of a Handful of Truths. But Wells doesn’t seem to be interested in delving into her past as a means of tying it back to her career as a director, which makes Aftersun all the more intimate and impressive as a result of this earnest motivation for such detailed, subjective introspection. Indeed, it’s the subdued subjectivity of Sophie’s perspective that tinges every scene with only Calum in it with more complex shades of the memory Wells wants to explore, such as a scene where he’s wandering around in the nighttime streets and on the beach by himself, evidently consumed by an aimlessness he hasn’t, and probably won’t ever, put into words. Perhaps a moment like this—among other, more outwardly devastating moments the film shows later on—is a construct of Sophie’s, trying to make sense of the minutiae presented throughout these more concrete memories by offering a sense of clarity to something tragic that she knows is bound to happen down the line.

The craft behind Aftersun‘s creation also seems to be deeply adherent to Wells’ penchant for subtlety and immersion. Gregory Oke’s cinematography frames the gorgeous scenery lining the landmarks, beaches, and mountainsides Calum and Sophie visit with beauteous use of colour and expansive wide shots, with more intimate angles of Sophie and Calum in the close moments they share together. Visually speaking, Aftersun may not be outwardly showy about its imagery, but it’s the sly impact in moments that make subtly effective use of reflections in glass or observations from a distance that really work in tandem with the film’s more patiently melancholic undercurrent. Complementing Oke’s work, in particular, is also Blair McClendon’s editing, which merges together visually related bits of imagery from the vacation while gently navigating through each medium that Sophie uses to navigate the memories of this particular vacation, giving us the impression of a stream of consciousness that’s just as coherent as it is free-flowing.

With the number of multitudes both Calum and Sophie contain, Mescal and Corio are respectively eerie at how skillfully they manage to convey such rich internal complexity. For such a young breakout actress, Corio’s charming work should almost instantly endear one to the precocious curiosity of someone like Sophie, a witty preteen slowly growing into her own self as she starts to learn more about how much that maturity entails from the older teens and adults around her. Right next to her, Mescal proves himself to be one of the most exciting up-and-coming actors of our time—hot off the heels of striking performances in Normal People (2020) and The Lost Daughter (2021)—affirming his skill in navigating the most delicate parts of human emotionality through his performance of a man clearly struggling with looming demons cut from various cloths, all the while failing to articulate those struggles to his daughter. And with both of these actors matching their chemistry to a pitch-perfect degree, the camaraderie, naturalism, and charm of Calum and Sophie’s father-daughter relationship are so effortlessly constructed it needs no further convincing or introduction: a father who wants to provide more than what he has, matched with a daughter who wants to learn more about the world beyond the limited knowledge and experience offered to her.

There’s a recurring motif interspersed between the more objectively shot scenes and Sophie’s VCR footage; that of a strobe-lit dance floor, where an adult Sophie pushes through the crowd trying to search for her father, the setting around her obscured by darkness and how everything in that room blinks in and out of view. If there was ever a clearer way to convey the slipperiness of memory, this is the mesmeric metaphorical space Sophie exists in to sift through that—a dark, void-like room whose visibility is limited to a series of disparate near-freeze-frames instead of the more continuously moving images more familiar to film as a medium. But as Aftersun grows closer to its quiet stunner of a conclusion and final shot, the thematic ambiguity of that room spiritually permeates into every corner of the sights we’ve just seen and the way we’ve gotten to know Calum and Sophie. The clear, moving, and laid-out answers Sophie so yearningly demands are exchanged for blinking outlines in the dark: things that can only be traced of the love that exists between her and Calum, only ever filled in and given motion by the details Sophie finds as she looks through her already impressionable, malleable memories.

“Love dares you to care for the people on the edge of the night… / to change our way of caring about ourselves,” David Bowie’s voice echoes in one scene; as if reminding the audience and Sophie of what’s most urgently at stake here, during Aftersun‘s painstakingly emotional search through the past. It may not be in the act of fully understanding our loved ones that our love for them grows stronger, but it may very well be in how we dare to try that love forms and persists, as something that haunts and is haunted by the nebulous nature of the memories we keep.

UK • USA | 2022 | 96 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Charlotte Wells.

starring: Paul Mescal, Frankie Corio, Celia Rowlson-Hall, Brooklyn Toulson, Sally Messham, Spike Fern, Harry Perdios & Ruby Thompson.