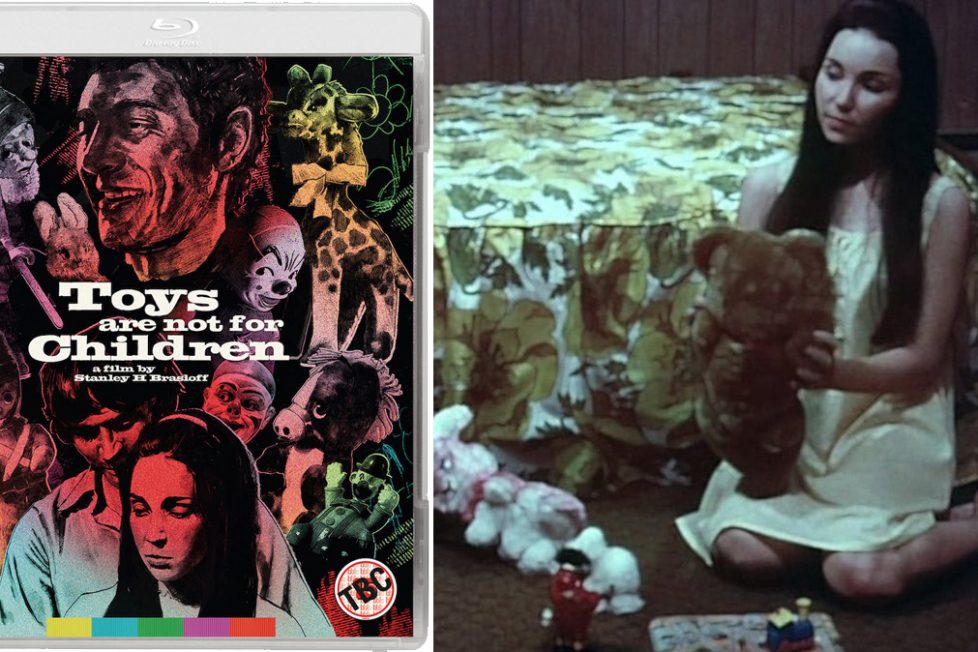

TOYS ARE NOT FOR CHILDREN (1972)

An emotionally-stunted woman with an unhealthy fixation on her long-absent father and the toys he gave her as a child, becomes a prostitute who specialises in pleasing old men who want to play daddy with her...

An emotionally-stunted woman with an unhealthy fixation on her long-absent father and the toys he gave her as a child, becomes a prostitute who specialises in pleasing old men who want to play daddy with her...

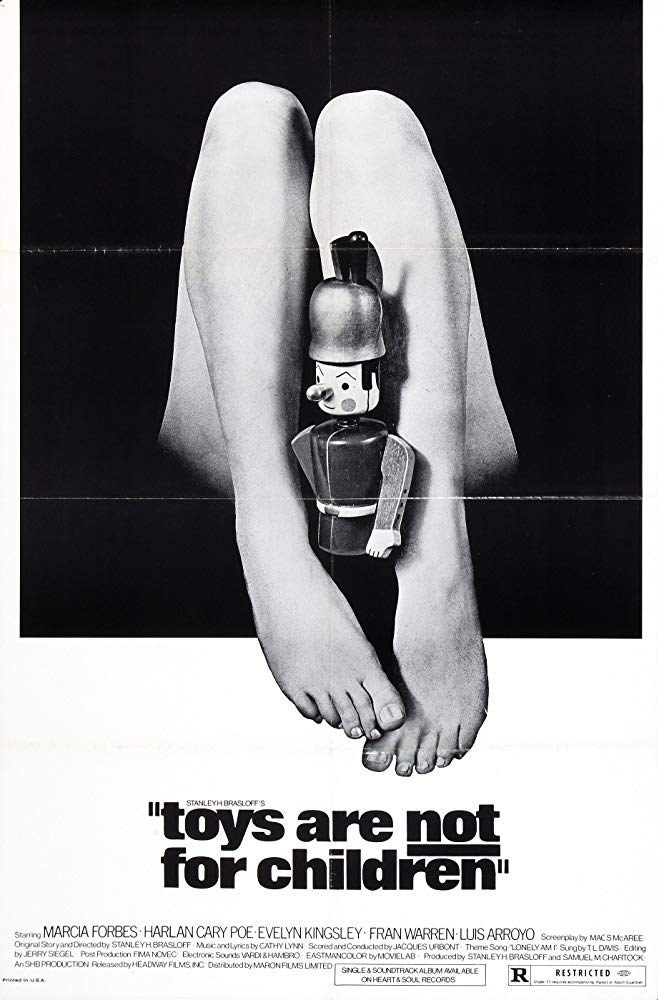

There are many things Toys are Not for Children will make you feel. Voyeuristic. Uncomfortable. Unclean. But it’ll never make you feel good. It revels in how it makes audiences feel just as horrible as its characters. In the film’s original advertisements, a grave voice-over warned about what one could expect to see: a lurid promise that you won’t have seen anything like it. Those warnings might seem quaint now (like grandparents warning you away from something you wouldn’t blink at), but the claims don’t seem so out of place for a film like this. It’s good manners to warn people about just how nasty this film can get… but for those into grubby exploitation cinema, the stark warnings are an unfulfillable promise.

Toys are Not for Children does its best to fulfil its promises, to scrape the bottom of the barrel of decency and spread the findings over grotty bits of cut-up celluloid. Reactions will be (and have been) wildly divided—but then exploitation cinema wouldn’t be what it is if it didn’t have some turning away in disgust, and others heralding these films as cult classics. This is a movie primarily designed for lovers of sleaze, but it does have merits that even a highbrow cineaste should consider. At its weirdest points, it has a down-and-dirty vibe that makes it feel like it could suddenly slip into being a porno, but it doggedly refuses to give up its psychological and emotional core which keeps it from losing sight of its troubled ideas. Pleasure isn’t of importance here.

It functions in an oddly similar way to professional wrestling. Its target audience wants something outrageous and dangerous but within the parameters of knowing it’s not real. It wants to show us something emotionally raw and controversial, while we want to repeat that classic mantra: “it’s only a movie, it’s only a movie, it’s only a movie…”

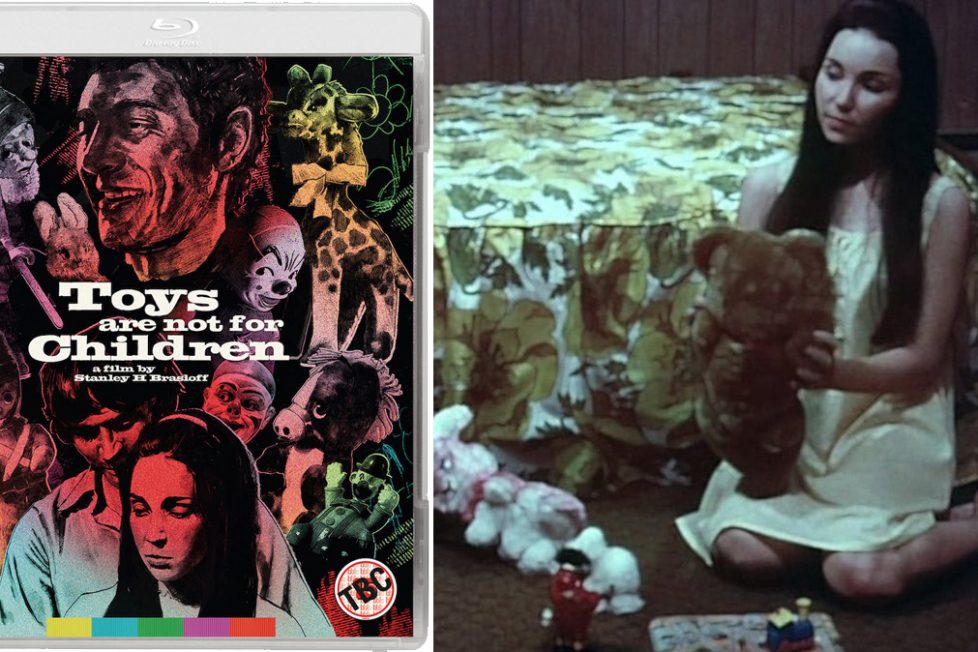

The story follows 20-year-old Jamie Godard (Marcia Forbes), an emotionally stunted and infantilised woman who, unable to get over the trauma of an absentee father, struggles through psycho-sexual desires and a broken marriage before turning to sex work as an outlet for her taboo desires.

If that sounds about as sleazy as exploitation cinema can get, it’s worth noting this isn’t too far removed from a particular cornerstone of Greek playwriting. Respected art and the lowest of the lowbrow aren’t as diametrically opposed as they might seem! It doesn’t take long before outrageously trashy cinema gets compared to great artistry. Jackass: The Movie (2002) was favourably compared to Charlie Chaplin’s oeuvre by many critics. Freddie Got Fingered (2001) has recently inspired video essays questioning whether it is, in fact, a Dadaist masterpiece. Suddenly, Greek Tragedies don’t feel too far removed from Toys are Not for Children.

Director Stanley H. Brasloff doesn’t hide his aspirations. For a film as unapologetically grimy as this one, it has a surprising (if small) sense of ambition and is taboo-busting in its psychological approach. The aims may be modest, and a truly meaningful thesis out of its sweaty grasp, but it’s unexpected that Brasloff should want his film to say anything at all. It’s even more surprising that he prioritises the film’s sickly ideas over its titillation, meaning that any weirdo watching this for kicks is in for a nasty surprise!

Brasloff’s film is both sympathetic and fatiguingly harsh towards Jamie. Positioned as naïve and ignorant of her own emotions, the film theoretically should be about her exploring herself and growing; in typical exploitation fashion, it’s instead about watching the knot tighten as Jamie’s slide into self-destruction reveals how deep her damage goes. Brasloff’s script is angry in her defence. Every man in her life wants something from her and, usually, it’s the same thing. Brasloff is careful to show the psychic pain this causes, and the total lack of self afforded to people who other people have decided are their ‘possession’.

Forbes, who’s good if a little amateurish in the role, is clever casting as Jamie. Before other people have even called her the name, there’s one thought that comes to mind when watching her: doll. Her features and face shape, particularly when seen in the toy shop that she works in, are purposefully reminiscent of that of a doll. The exact kind of doll she collects and treats with love. Even if the film is sympathetic towards her and attempts to expand her psychology, there’s something slightly alarming and creepy in this objectification of Jamie, particularly in its constant comparison of her to a child.

But then, this is an exploitation film from 1972. It almost goes without saying it’s going to be uncomfortable. And it could further be argued that the positioning of Jamie as a child and a doll is not how the film sees her, but rather how misogynist males see her. It’s an interesting tension because a film as murky and amoral as this never tells us what it believes—we take from it what we want. Further incestuous developments are some of the film’s most nauseating and troubling, the ‘daddy issues’ trope used as a convenient answer to any question we might have about Jamie.

Aside from a few exceptions, decoding what the film believes about any given topic is futile, as it seems to exist entirely in its own moral universe. There’s almost no point applying understood and accepted morals to the film, as it refuses to engage with them. The film is the equivalent of somebody with no filter, and we’re left wondering whether they really meant what they said. Much of the time, one gets the sense that Brasloff is that kid in school, a few years above you, who comes around every now and then asking “wanna see something fucked up?”

It’s also emotionally tumultuous, unable to decide what mood it’s in at any given time. For instance, Jamie’s introduction to sex work is refreshingly positive. A film from the ’70s would typically carve a spot here for it’s lowest, seediest point, but Jamie has freedom and autonomy in this choice. Until, inevitably, the film decides at random intervals that things are awful again and the mood should swing back viciously. A shifting mood isn’t a bad thing, as it can reflect the constant overlapping and clash of emotions but, maddeningly, Brasloff seems to hit the same beats over and over. Jamie’s arguments with her mother are frustratingly repetitive, hitting the film’s points about the fear of turning out just like your parents like a sledgehammer hitting a nail.

If the film has trouble making up its mind, it’s a little more decisive in the last stretch, which contains some of the most screwed-up, funny, and genuinely shocking minutes that Arrow Video is ever likely to release. It works because it’s not afraid to follow shocking laughter with something sadder and almost guilt-inducing. It’s a strange experience, like a stand-up comedian punching you in the face for laughing at their joke—but it oddly works in the film’s dank, dirty mode of operating.

It’s an acquired taste, from its shoddy sets to its strange, Casio-keyboard score. But it has a life to it; a certain twisted charm that makes the whole flawed thing quite unforgettable. It’s a movie designed to disgust and, in its own small way, make us ask questions. Depending on your stance, your question will either be “what were the director’s intentions?” or “why did I just watch this?”

director: Stanley H. Brasloff.

writer: Macs McAree (story by Stanley H. Brasloff).

starring: Marcia Forbes, Harlan Cary Poe & Evelyn Kingsley.