THE ADDICTION (1995)

A New York philosophy grad student turns into a vampire after getting bitten by one, and then tries to come to terms with her new lifestyle and frequent craving for human blood.

A New York philosophy grad student turns into a vampire after getting bitten by one, and then tries to come to terms with her new lifestyle and frequent craving for human blood.

Director Abel Ferrara and writer Nicholas St. John earned notoriety as enfant terribles of the indie film scene with their first two feature films, Driller Killer (1979) and Ms.45 (1981). Those were very low budget, but the verve and passion of the filmmakers is clearly apparent. It wasn’t really until a decade later they managed to live up to their reputation, with a double-whammy of The King of New York (1990) followed by Bad Lieutenant (1992).

With The Addiction (1995) they returned to their guerrilla roots, shooting on the streets of New York with one camera and no permits, using non-actors to play alongside a small but impressive cast. It’s just as edgy as their earlier work, and similarly peppered with disconcerting realist scenes—real junkies, recognisable places—but shot in quality black-and-white. It could almost be called beautiful if it weren’t so gut-wrenchingly brutal. Ferrara had been inspired to go monochrome for his post-modern vampire story after seeing Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire (1987) and as a nod to F.W Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922).

The Addiction isn’t simply another vampire movie where bloodlust becomes a metaphor for drug addiction or the spread of disease. Those themes have been part and parcel of vampire stories from the start—ever since Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Nicholas St. John’s joyously intellectual script takes us beyond that. He was a philosophy graduate himself and by making the central character, Kathleen Conklin (Lili Taylor), a student studying for a master’s in philosophy, he manages to shoehorn in extensive existential dialogues.

We join her in class as their professor (Paul Calderon) assigns them to read from Kierkegaard’s The Sickness unto Death (1849) and Nietzsche’s The Will to Power (1901). Now, to those philosophy fans in the audience, this is like a big neon sign indicating the major themes about to be tackled throughout the The Addiction… The professor is seen standing in front of a chalkboard on which is written a reading list of equally heavy-duty thinkers. I particularly enjoyed the visual humour as he delivers his lines whilst erasing the title, Being and Nothingness, Sartre’s influential treatise of 1943 on ‘free will’ and ‘bad faith’. As Abel Ferrara advises during his audio commentary, “Google-up those guys.”

Whilst walking back to her apartment, Kathleen’s accosted by an elegant lady (Annabella Sciorra) who, with superhuman strength, drags her into a dark alley and bites her in the neck. The scene is lit through railings and gratings that cast a grid of shadow and this effect, along with Sciorra’s stylish appearance reminded me a little of The Hunger (1983), her haircut even resembles Susan Sarandon’s. That’s about as ‘glossy’ as The Addiction gets, and this brief allusion is just a red herring. We won’t be watching slow motion curtains billowing through smoky shafts of light, and instead of Bauhaus performing “Bela Lugosi’s Dead”, we get Cypress Hill singing “I Wanna Get High”.

Kathleen goes to the police and ends up recovering in hospital, where she’s assured the wound is clean and her fever couldn’t be AIDS as that disease wouldn’t manifest so soon. The mere mention of AIDS was capable of inducing a phobic response as it was still widely misunderstood in the mid-1990s. It hadn’t yet been 10 years since HIV was identified and it was certainly a growing problem in New York.

Kathleen attempts to return to her normal life, but something has changed. She can no longer keep her food down and begins to crave something else… is she suffering from a disease, or withdrawal symptoms? She finds that when she injects herself with the blood of others, she feels better again… much better. The vampires of The Addiction don’t magically sprout fangs, and the use of syringes and razors hark back to another film that pushed the post-modern vampire canon, George Romero’s Martin (1978).

It does adhere to most of the established rules of the genre, though. The vampires shun daylight. They have inhuman strength. They are able to mesmerise others but are challenged by Christian ideology and symbolism. The scene where Kathleen seduces her professor is the only vague nod to the eroticism often present in the genre, but here it is a drug-buddy set-up instead of anything overtly sexual. Having been reminded of AIDS shortly before, it’s difficult to watch as Kathleen uses her hypodermic to withdraw blood from his veins and inject it into her own, even more so when she does the same thing with a derelict she stumbles across on a side street!

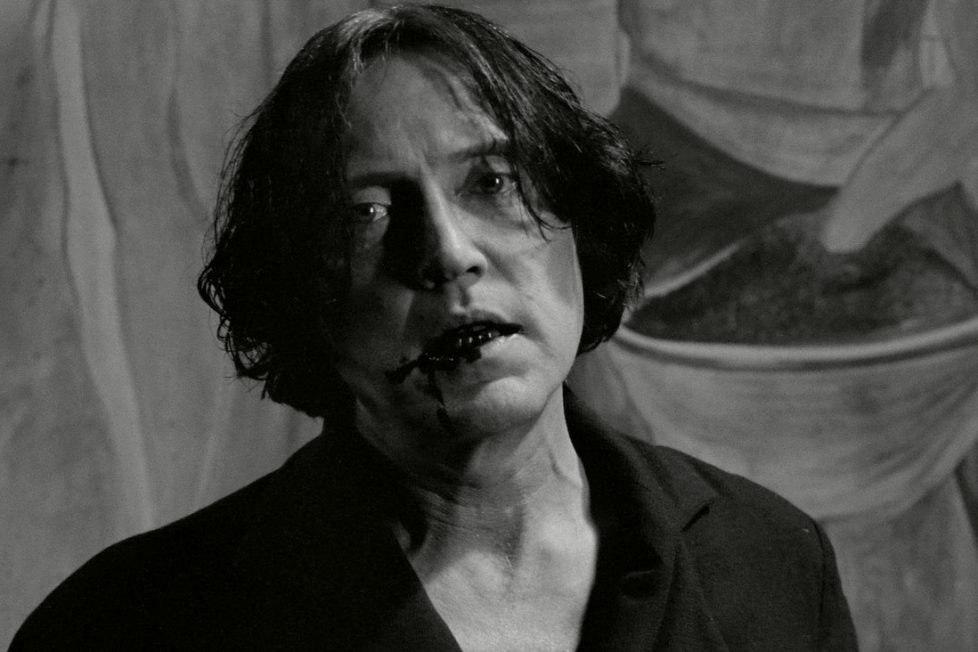

Lili Taylor is outstanding and well suited to the role. At times she looks sweet and vulnerable. Then she can be miserable and morbidly morose or ferociously feral. Her fellow philosophy student, Jean (Edie Falco), is a perfect foil for her descent into debauchery—you may recognise her as Carmela, Tony’s wife in HBO’s The Sopranos. Another one of Kathleen’s notable victims is Black, played by Fredro Starr, award-winning rapper from the New York Hip-Hop trio, Onyx who also contribute the song “Better Off Dead” to the soundtrack.

The Addiction shares its central themes and structure with Ferrara’s second film, Ms.45—not a sequel, more a bookend. Both stories are about a woman who is violated in an assault and is changed by the experience. They attempt to turn victim into victor. Both women go on killing sprees, the violated becoming the violator, and both films climax in a party that descends into an orgy of death. The difference being that the heroine in Ms.45, Thana (Zoë Tamerlis) is mute. She’s denied a voice and learns to ‘speak’ via a stolen pistol, whereas in The Addiction Kathleen is so eloquent as to use language as a ‘weapon’. Some of her tirades are almost, but not quite, worthy of a Lydia Lunch monologue.

Interestingly, Lydia Lunch’s story Bloodsucker (adapted into a comic book by artist Bob Fingerman in 1992), features a young girl who also uses a syringe to transfer the blood of others into her own veins in another existential psycho-sexual metaphor for addiction and the struggle to assert the will of the self over the will of the other. But, as you might expect, Lunch offers no resolution or redemption in her transgressive tale.

In King of New York, Christopher Walken’s pale and detached character riding the NY subway at night is almost vampiric, there’s even a clip from Murnau’s Nosferatu. When he turns up in The Addiction as Peina, an ancient vampire, we’re treated to a showcase of classic Walken. He dominates the screen with a characteristically powerful and slightly askew performance as he shows Kathleen what she’ll eventually become, but only if she possesses enough strength of will. His scene is the pivotal point in the narrative and contains some of the lighter dialogue and also the most edgy and gross-out moments. His training as a dancer is evident as he moves with such a grace and restrained energy. He discusses Naked Lunch by William Burroughs, Beyond Good and Evil by Nietzsche, quotes some choice Baudelaire, and feasts on Kathleen’s blood with animalistic slurps and gurgles.

Cinematographer Ken Kelsch, a Vietnam veteran and long-time friend of Ferrara who’d photographed Driller Killer and Bad Lieutenant, does a great job here. Often, he uses hand-held camera and really works with the actors, responding to the beat of their performances. The luscious monochrome photography is beautifully handled and makes the bloody scenes even more effective. Not only does the black blood have a striking graphic effect, chocolate syrup was used as the substitute, so the actors didn’t need to pretend they were enjoying the flavour, it actually did taste good! A new slant on the phrase ‘death by chocolate’.

The Addiction may not be to everyone’s tastes. Some may find the philosophising a little heavy-handed or be frustrated by the references that come thick and fast throughout. The visceral horror may be too strong for some, but not those familiar with the vampire genre, which it treats with great respect. The use of archival images showing the aftermath of war atrocities – mutilated flesh and the emaciated dead piled into mass graves—are by far the most harrowing sequences and beg the big questions about the nature of human evil and concepts of redemption. It’s a memorable, challenging and singular viewing experience with a satisfying conclusion and would certainly bear re-watching by those it does not repel.

director: Abel Ferrara.

writer: Nicholas St. John.

starring: Lili Taylor, Christopher Walken, Annabella Sciorra, Edie Falco, Paul Calderón, Fredro Starr, Kathryn Erbe, Michael Imperioli, Jamel ‘Redrum’ Simmons & Nicky D.