‘Zen and Sword’—The Miyamoto Musashi Saga at Toei (1961-65)

In the early-1960s, Toei launched a film series focused on a legendary samurai – a five-part saga adapted from the works of Eiji Yoshikawa.

In the early-1960s, Toei launched a film series focused on a legendary samurai – a five-part saga adapted from the works of Eiji Yoshikawa.

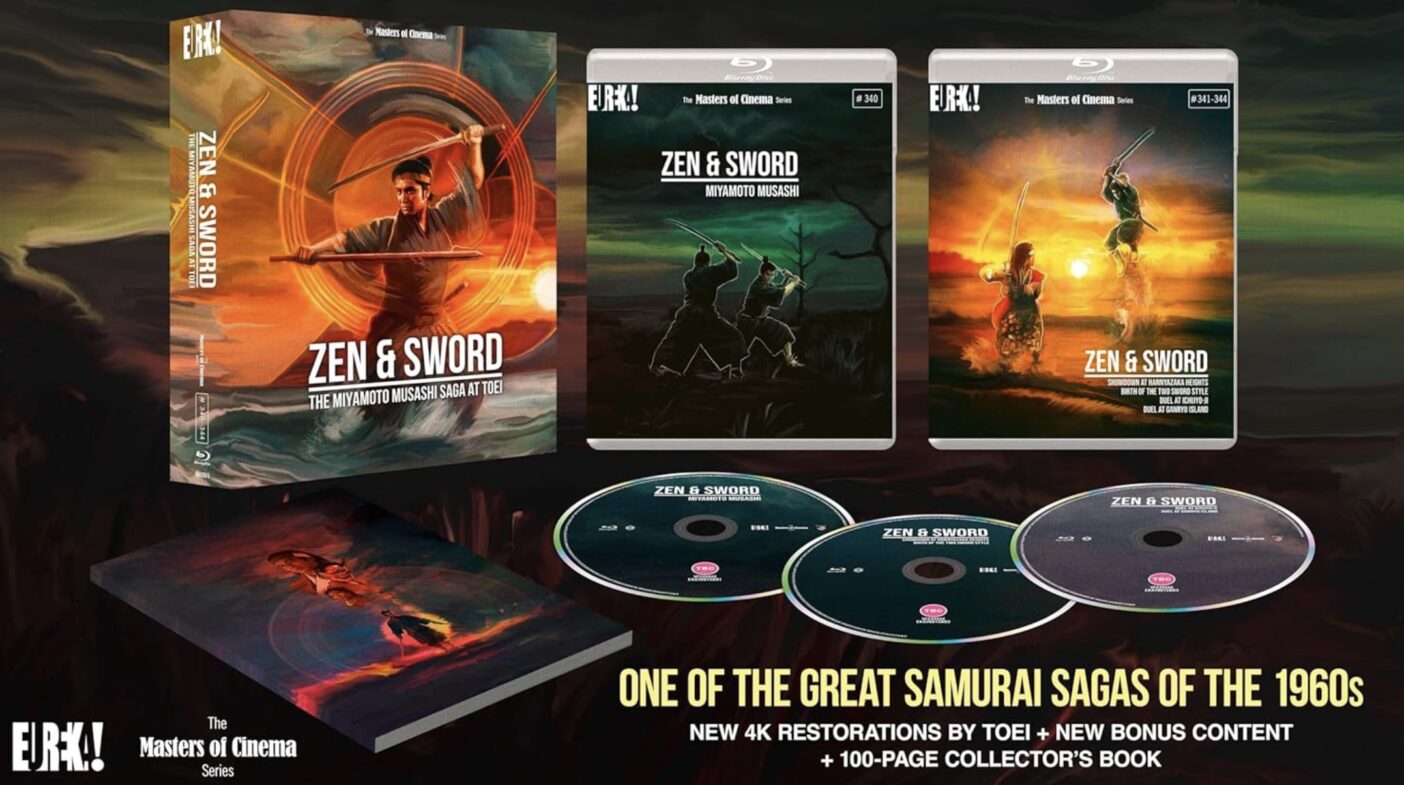

Miyamoto Musashi is a legendary swordsman portrayed in scores of mainstream films, providing the inspiration for countless others and appearing across manga, anime, and games. For fans of samurai cinema, the latest addition to Eureka Entertainment’s ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint is a landmark event: Tomu Uchida’s five-film Miyamoto Musashi epic, presented in a handsome three-disc Blu-ray box set.

Each film has been restored from 4K scans of the best available source material, supervised by Toei, the original production studio. Although presented in five chapters, the series comprises one continuous narrative with a combined runtime of 566 minutes. This makes it the second-longest film ever made in Japan, narrowly pipped to the post by Masaki Kobayashi’s wartime epic, The Human Condition (1959-1961), which ran for 579 minutes. Still, at nearly 10 hours, it offers an immersive experience when watched back-to-back—perhaps over consecutive nights like a modern miniseries—an approach I heartily recommend.

Miyamoto Musashi was a real historical figure who became a legendary folk hero. Far from an ordinary samurai, he earned the title of kensei—a distinction granted to only the greatest living swordsman at any one time. For long stretches, he lived as a wandering ronin; he’s famed for an unkempt appearance that reflected a life lived in a constant state of alertness. Renowned for developing his own combat techniques, he pioneered an unorthodox two-sword style. In contemporary media, he’s perhaps best known as the template for Ogami Ittō, the ‘Lone Wolf’ in Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima’s popular manga series and its subsequent film adaptations.

When Toei Studios put Tomu Uchida in charge of this epic biopic, he already faced a benchmark in Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai Trilogy (1954-56), produced by Toho. That sequence was immensely successful, with the first instalment, Samurai I: Musashi Miyamoto (1954), winning the 1955 Academy Award for ‘Best Foreign Language Film’. Its international appeal was due in part to a deliberate attempt to mimic the widescreen spectacle of Hollywood epics, showcasing lush Eastmancolor and a clean, mostly linear narrative.

Tomu Uchida’s response was no less a big-screen experience. It was also released internationally as Zen and Sword, the umbrella title Eureka! Entertainment’s chosen for this excellent pentalogy box set. It’s a fitting title, as the ambiguous protagonist begins as Shinmen Takezō—an uncouth youth who has yet to become the most famous swordsman in Japanese history.

A young ruffian survives the decisive Battle of Sekigahara and embarks on the arduous path towards the way of the samurai.

The first film opens with a striking sequence: Takezō (Kinnosuke Nakamura) crawls among the dead in the aftermath of the Battle of Sekigahara. This places the start of the story in the ninth month of the fifth year of the Keichō era—October 1600 CE. We meet him at his lowest point; a defeated man, animalistically slithering through mud and blood in the half-light of dawn. Yet he has survived the decisive battle that ended the “Warring States” period and established the Tokugawa Shogunate as Japan’s supreme power, outranking even the Emperor. This period has been revisited countless times and served as the backbone for the recent hit TV miniseries Shōgun (2024)—itself a remake of the 1980 adaptation of James Clavell’s novel. It’s also the historical backdrop for the influential Shinobi films (1962–1970) and Shōgun’s Samurai (1978), the latter recently restored by Eureka! and also starring Nakamura.

Takezō eventually finds his wounded friend, Matahachi (Isao Kimura). We learn they fought under Ukita Hideie, placing them on the losing side—those loyal to the Toyotomi clan who were crushed by Tokugawa Ieyasu. While not all historians agree that the young warrior who would become Musashi was at that battle, most who do believe he actually fought for the winning Tokugawa side. Such a fact would, of course, derail the narrative of the two men as fugitives.

Tomu Uchida’s film series doesn’t pretend to be a documentary; it’s a “history-adjacent” parable based on Eiji Yoshikawa’s epic novel, first serialised between 1935 and 1939. While the author conducted extensive research, corroborated sources weren’t easily available in the 1930s. Although he incorporates verified events, the story is largely fiction and embellishment. Even the abridged 1981 English translation ran to over 900 pages, providing Uchida with a massive wealth of source material. Fortunately, he remains faithful to the spirit of the book.

In the dawn light, the two bedraggled soldiers spot a figure stripping corpses of their valuables. Affronted, they challenge the scavenger, only to discover it’s a woman, Okō (Michiyo Kogure). She takes them back to her farmstead, where she lives with the younger Akemi (Satomi Oka), an orphan she raised as a daughter. The women know sheltering fugitives is dangerous, but they decide the benefit of having men around outweighs the risk. In an uncomfortable scene that serves as a clear metaphor for sexual intimacy, Okō saves Matahachi’s life by using alcohol as an antiseptic and sucking the infection from an arrow wound in his thigh.

While delirious, Matahachi dreams of his betrothed, Otsu (Wakaba Irie), playing her flute. This segue introduces us to Takezō’s sister, Ogin (Akiko Kazami), and Matahachi’s mother, Osugi (Chieko Naniwa)—more often called “Obaba,” a respectful term for an old woman or “Grandma.”

Then, the style shifts. Dialogue is replaced by deranged laughter, highlighting the characters’ desperation as civilised order collapses. Uchida’s theatrical storytelling might grate on some, but it’s a brief interlude that effectively compresses events to drive the central narrative forward.

Matahachi becomes infatuated with Okō and seemingly forgets Otsu, while Takezō forms a platonic bond with Akemi. A few more key characters have yet to appear, but the core group is established—individuals who will separate and reunite through a series of unlikely coincidences that stretch credulity for the sake of the plot.

We first see Takezō in action when bandits attack the farmstead to steal food and abduct the women. They hadn’t counted on the young soldiers. Although Matahachi is too weak to help, Takezō’s ferocity is brutal; he dispatches the raiders with a wooden baton and unbridled fury. He even pursues their leader on horseback, gleefully bludgeoning him to death.

This episode echoes the real Musashi’s duels; aged 13, he reportedly killed a trained swordsman with nothing but a heavy stick. Here, Takezō is meant to be 17. Kinnosuke Nakamura, one of Japan’s greatest actors, was approaching 30 at the time. While he isn’t entirely convincing as a teenager, he perfectly conjures the energy, belligerence, and bravado of adolescence.

Returning to the farmstead filled with hubris, he finds that Matahachi and the women have fled, fearing the bandits’ return. He decides to head home to tell Obaba her son survived and to reunite with Ogin. It doesn’t go to plan.

Obaba becomes a recurring character motivated by a vindictive resentment of Takezō, whom she blames for her son’s disappearance and his abandonment of Otsu. She initially seems relieved to hear her son is alive, but it’s a ruse. She’d rather pretend he died in battle than bear the dishonour of his desertion. After inviting Takezō to bathe, she informs Aoki (Tokubei Hanazawa), an official hunting fugitives, of his whereabouts. Through sheer force, Takezō escapes his captors—but not before learning they have taken Ogin prisoner.

I assume Obaba was intended as semi-comedic, as she is such an over-the-top caricature. I suppose it’s an inventive twist on the “old woman” archetype to have her wielding weapons and attempting to kill Takezō throughout the five films. However, the joke quickly wore thin for me; despite the change of pace, my heart sank every time she appeared.

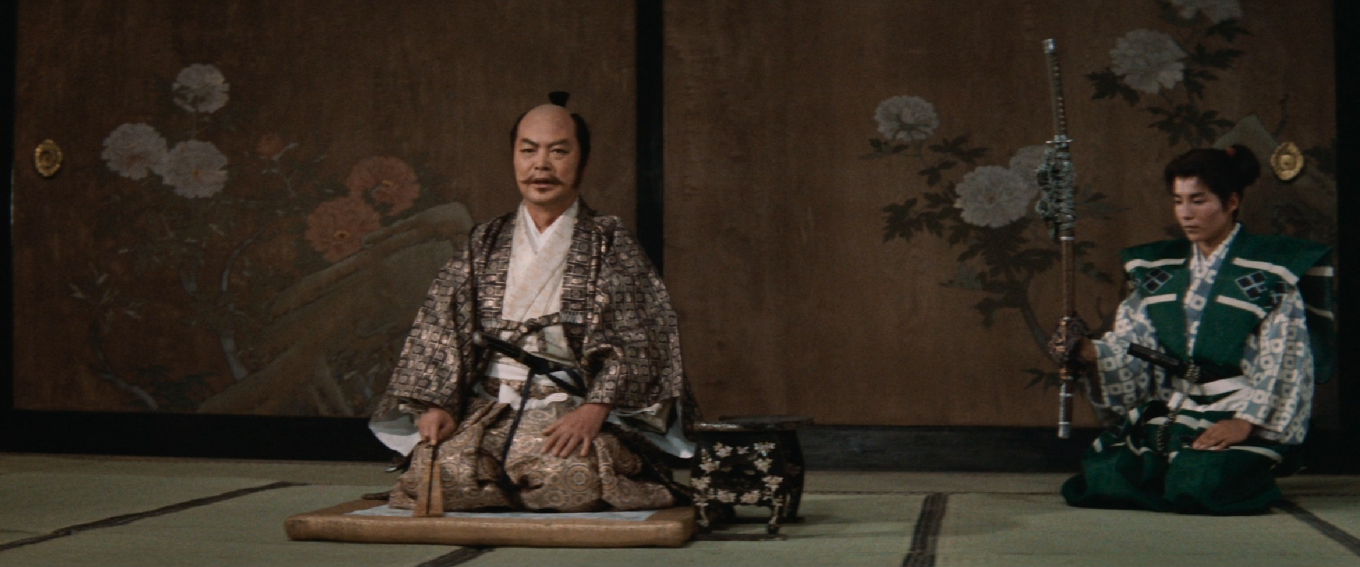

My favourite recurring character is the unconventional Buddhist monk, Takuan (Rentarô Mikuni). Based on a historical figure who perhaps left a greater cultural legacy than Musashi himself, Takuan was known for a quick wit that Mikuni captures perfectly. The real Takuan moved in high circles, advising the Shōgun and the Imperial family. He is remembered for his contributions to gardening, calligraphy, the tea ceremony, and for embedding Zen philosophy into martial arts. He even created the famous yellow daikon pickle that bears his name.

Rather than using force, Takuan captures Takezō through reason and brings him to face judgement. He manages to postpone the execution by suggesting the fugitive be hung from a branch of a thousand-year-old cedar for several days. This clever plan aims to replace hubris with humility while testing if any locals feel the man is worthy of mercy. In a way, he creates a community court.

Takuan sees potential in Takezō and challenges him to become a “whole human” instead of revelling in his beastly nature. The scene where Takezō breaks down in an outpouring of emotion is a showcase of Nakamura’s power—an intensity he rarely gets to unleash over the span of this pentalogy. To see the actor at his best, I’d also recommend Shōgun’s Samurai and the gorgeous The Fall of Ako Castle (1978).

The first Musashi film is essentially an extended prologue. I won’t give too much away for those seeing the pentalogy for the first time, though it’s hardly a spoiler to say Takezō survives his ordeal—after all, there are four films to go!

One liberty Uchida’s saga takes is giving Musashi a specific motivation for his dedication to the sword. Takuan takes him to Shirasagi Castle and tells him he is the only direct descendant of the Akamatsu Clan. He instructs Takezō to hide in a darkened room in the “haunted” tower, where the walls are stained with the blood of his kin.

In a gothic sequence, the ghosts of these ancestors appear to him. They set him a quest to regain the noble standing befitting his clan. Thus, the man who will become Musashi begins his first hermetic stint, locked in the tower with a pile of books to build the spiritual understanding required to match his physical prowess.

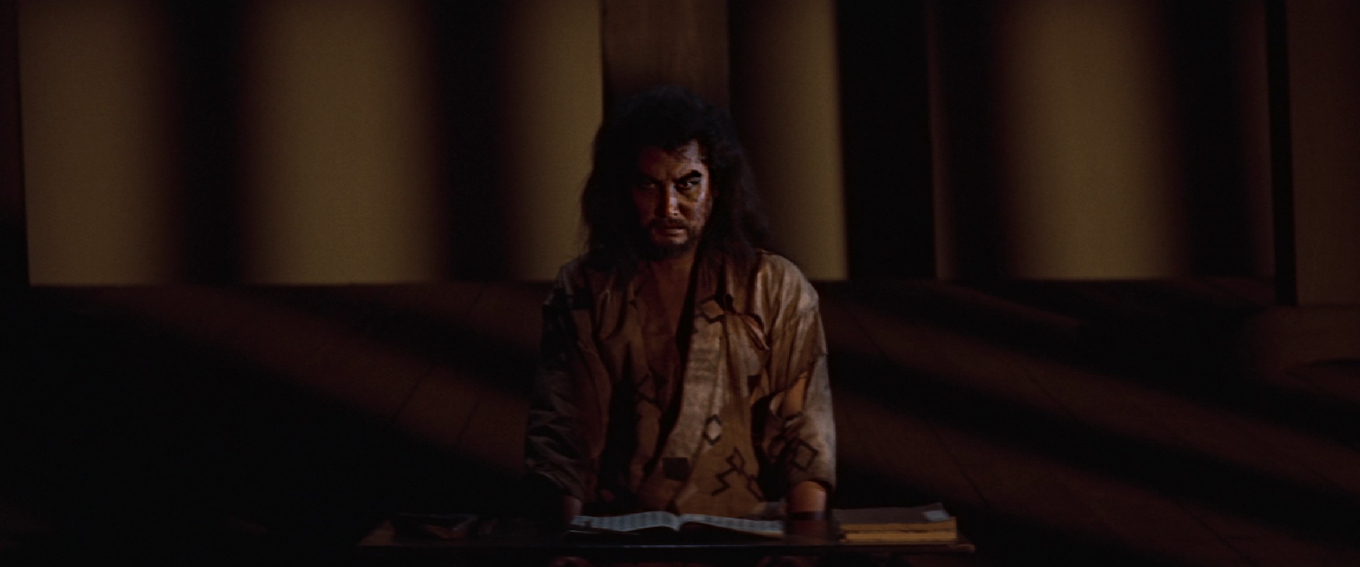

To survive, he must become fearless, both spiritually and physically. The final image is of Nakamura sitting cross-legged before an open book—grimy, dishevelled, and unkempt. His fierce eyes meet the viewer’s gaze as the camera closes in. Japanese audiences would recognise this iconic image and think: “Finally! This is Miyamoto Musashi.”

JAPAN | 1961 | 110 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Musashi emerges from a period of learning and contemplation, soon coming into conflict with a rogue group of ronin.

The second chapter picks up after the man in the tower room has spent three years reading by the meagre light slanting through shuttered windows. Takuan arrives to invite him back into the world, hoping his barely restrained fury and physicality have been tempered by reason and morality. As the saga unfolds, however, we see that this process is by no means complete.

It is Takuan who suggests a new name for this new man: Miyamoto Musashi (宮本 武蔵). This is a clever play on traditional kanji; we learn that ‘Takezō’ can also be read as ‘Musashi’. This wordplay is likely a carry-over from Eiji Yoshikawa’s (吉川 英治) epic novel, as most historical sources don’t mention Takezō as his birth name. Nevertheless, the name change is a sharp device to mark a transition in the character’s development that amounts to nothing less than a symbolic rebirth. It may also have appealed to Uchida, who dropped his own birth name, Tsunejirō, to adopt the professional moniker ‘Tomu’—which, when written in kanji, can be read as ‘spitting out dreams’.

With A Living Puppet (1929), Uchida was cited as the progenitor of keikō-eiga, or ‘tendency films’. This Japanese genre, influenced by Soviet social realism, produced left-leaning melodramas featuring working-class protagonists—often mothers—pitted against high-ranking antagonists, bosses, and bureaucrats. These films reflected the hardships suffered in the aftermath of the 1927 Shōwa financial crisis, an economic crash exacerbated by the global Great Depression of the 1930s.

This provided the backdrop to the inter-war years of Uchida’s early career, and his first films clearly inform elements of this pentalogy. We see much of the action from the perspective of impoverished villagers, farmers, and redundant soldiers. Despite Musashi dominating the screen time, the narrative often pivots on interactions with women. Indeed, many of these women could be dismissed as mere plot devices—albeit integral ones—rather than believable characters. Otsu, Musashi’s potential romantic interest, is a notable exception. Wakaba Irie is eminently watchable throughout and isn’t given nearly enough screen time. She provides the narrative’s emotional heart and demonstrates great range, even if her performance occasionally veers into the theatrical or melodramatic.

Part two concludes after the chaotic showdown at Hannyazaka Heights. Here, various factions use codes of honour to manoeuvre Musashi into a position where he’s forced to confront a gang of unemployed ronin terrorising the territory. It’s the most violent battle yet, and Musashi is far from happy when he realises his blade has unwittingly served the interests of others.

JAPAN | 1962 | 107 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Now a formidable samurai Musashi develops his personal style of swordsmanship and first encounters his equally skilled rival, Kojiro Sasaki.

The difficult third chapter opens with the final scene of part two. Continuing in the same meandering, episodic mode, the chapter occasionally feels redundant and inconclusive—much like the bridging middle section of a trilogy. While the five films suffer from uneven pacing, maintaining a constant tempo across an epic of this proportion would likely have become either tedious or exhausting. Furthermore, Uchida repeatedly reinforces several themes, and the dialogue often reiterates information we already possess. At times, Musashi is even reduced to delivering lines to the air with no one but the audience to hear; it is a minor contrivance among many, yet one that doesn’t spoil the overall grandeur.

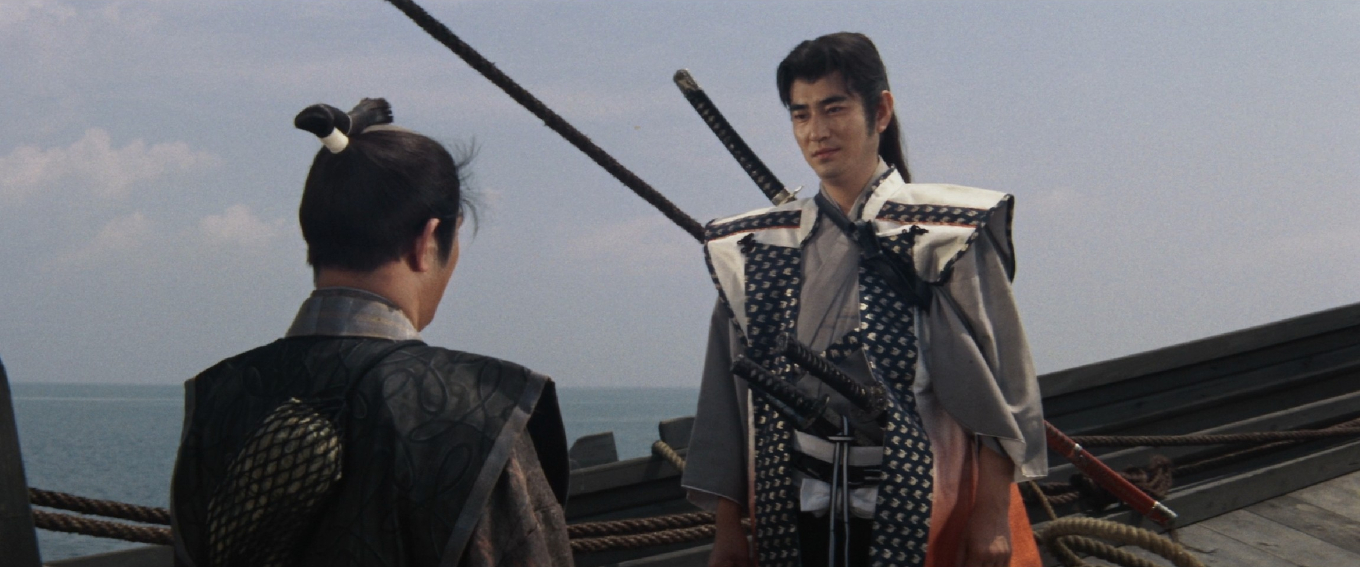

For me, part three was the weakest of the sequence, despite introducing Sasaki Kojirō (Ken Takakura), a real swordsman whose legend rivals that of Musashi in both fiction and history. Takakura was another hugely popular and prolific star of Japanese cinema, known primarily for portraying stoic, chivalrous yakuza. Here, he’s a dandy of a samurai sporting the finest clothes and an unusual sword with an extended blade, commissioned to his own design to suit his unique Ganryu style. He recurs until the finale of the fifth film, often seen in the background, watching and taking the measure of Musashi.

During Imperial Japan’s expansionist phase, Uchida followed the invading army into Manchuria and was commissioned to make propaganda films there. While many of these films were planned, few were actually made, and most are now lost. Their aim was to glorify Japan as the saviour of Asia, “liberating” China while portraying Communists as dishonourable gangsters.

The Japanese invasion and subsequent occupation of China, including the British Colony of Hong Kong, ended with Japan’s surrender at the close of World War II. Japan then became an occupied nation under US administration until 1952. During that period, freedom of expression was as strictly curtailed as it had been under the Imperialist regime; American censors only approved content that aligned with their notions of a reconstructed national identity. This discouraged anything that seemed to exalt the martial aspects of traditional culture—such as samurai stories—which were perceived as components of the mindset that led to Japan’s aggressive expansion during the early-20th-century. Interestingly, Eiji Yoshikawa’s original novel was written during the expansionist phase and the invasion of Manchuria, which Tomu Uchida experienced first-hand, while the filmed adaptation was produced after the war that brought that Imperial regime to an end.

JAPAN | 1963 | 104 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

Musashi finds himself in an untenable position and must battle a small army alone and make a fateful choice that will compromise his very humanity.

The next section is the strongest in every respect: story, character, pacing, action, visual composition, and cinematography… it all comes together perfectly. Uchida is known for dynamic camerawork and, despite minimal experimentation here, there are some truly ambitious tracking and crane shots to keep things interesting. The style resembles what audiences had come to expect from one of Toei’s flagship prestige epics.

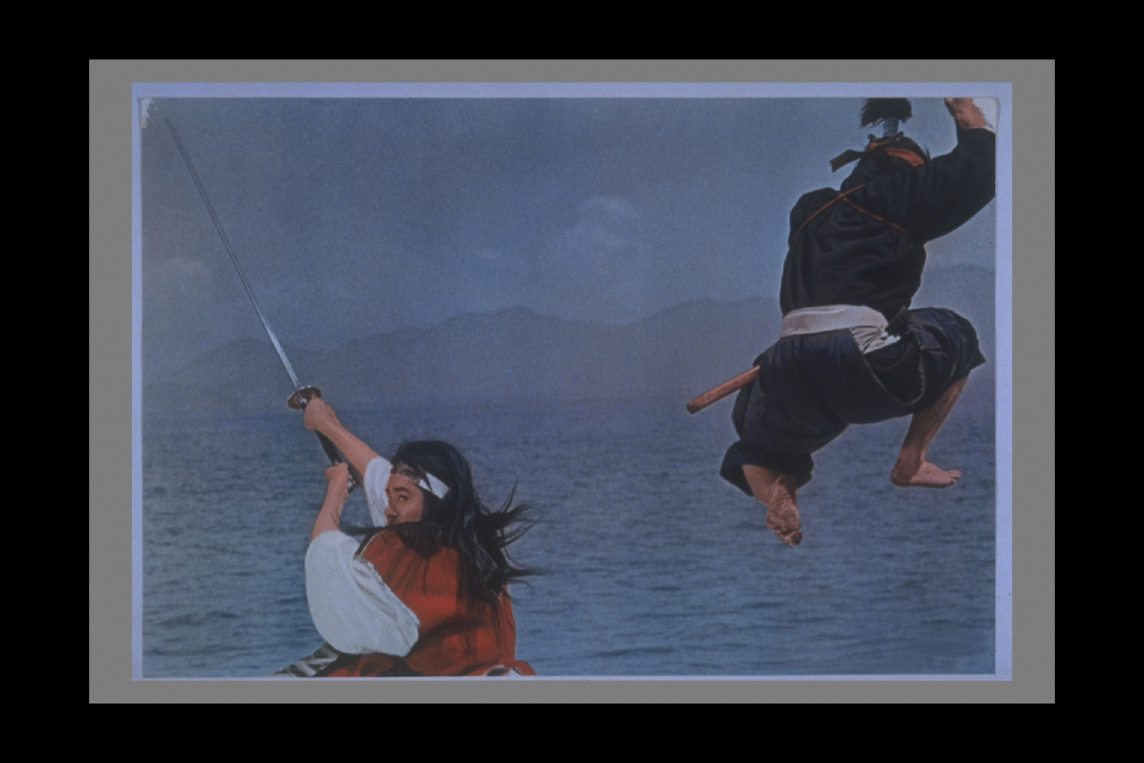

The titular duel—with its tense build-up as two men approach each other in a highly filmic snowfall—is a fine piece of cinema, and the influence of the classic Western showdown is palpable. The outcome sparks a vendetta that culminates in Musashi facing the swordsmen of an entire clan in the pentalogy’s climactic scene. Not only is the action ambitiously staged and choreographed, involving nearly a hundred samurai, it’s also the most stylistically experimental—exactly what Uchida’s fans may’ve been waiting for.

Right from the opening scenes of part one, Uchida confidently uses expressive colour as a narrative device to reflect Musashi’s emotional state. When he’s in “fight mode”, he relinquishes reasoned control to the uncompromising code of Bushido. There’s no room for emotional ambiguity; his state of mind is reflected by a desaturated palette and high contrast between light and dark. No grey areas. Yet when he interacts with women, the colours are vivid, exploiting the saturation only Eastmancolor can capture. It’s as if the world only comes alive when he acknowledges his feelings—a metaphor for the balance and imbalances of broader society wherever there’s a steep gender gradient.

After Makoto Tsuboi photographed the first two instalments, Sadaji Yoshida took over as cinematographer for the remaining three. Both do sterling work, but part four features a standout sequence that’s both visually stunning and narratively pivotal. A decisive battle is shot entirely in black and white, creating a striking visual graphic while, on a more pragmatic level, removing the need for fake blood.

This is the point when Musashi allows his martial code of Bushido to guide him into actions that he, as a man, would’ve morally hesitated to commit. His internal emotional revolt is echoed in the breakdown of visual cohesion, as slick swordplay descends into stumbling, slashing chaos. Then, a sudden flash of colour arrives as the emotional impact of a questionable act collides with the euphoric realisation that he’s won against insurmountable odds. In his mind, survival seems justification enough. This version of Musashi is formidable, certainly, but remains an incomplete man—not a traditional hero at all.

JAPAN | 1964 | 128 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR • BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

The inevitable confrontation with Kojiro Sasaki looms and Musashi relinquishes all emotional ties as he risks everything.

He seems to move towards greater harmony in this final instalment when he briefly relinquishes his quest for the blade to adopt a young orphan. In doing so, he establishes himself as a protective, nurturing father figure, settling into the life of a farmer. Yet this respite is brief; it serves only to highlight what he has sacrificed in his pursuit of martial perfection. He also nears a sense of closure with Otsu, who is prepared to forgive his many human shortcomings. “I am drawn to your anguish and severity,” she confesses before he departs for the titular duel—one of the real historical Musashi’s most iconic moments.

Following the withdrawal of Japan’s armies, Tomu Uchida was stranded in Manchuria for nearly eight years. He spent this time teaching filmmaking between bouts of forced labour, internment, and Maoist indoctrination as dominance fluctuated between nationalist and communist factions. Carrying a wealth of harrowing experience and exposure to conflicting ideologies, he managed to return to Japan in 1953. While much had changed, cinema was once again dominated by contemporary melodramas. These often focused on women, who had been granted greater freedoms and constitutional rights under US governance.

However, with Japan’s sovereignty restored, the nation was grappling with a cultural identity that sought to rescue positive aspects of its heritage while confronting the indelible aftermath of the atomic annihilation of two major cities. This manifested, in part, through a renewed popularity for jidaigeki (period dramas) and chambara (samurai swordplay) movies. These films offered a way to examine contemporary problems through the lens of a mythologised past—a function not dissimilar to that of the Western in the United States. Indeed, the epic How the West Was Won (1962) was in production at the same time Uchida was embarking on his five-part saga based on the life of the famed “masterless samurai”.

The director’s own experience of wartime chaos echoed the Sengoku “Warring States” era, which preceded the comparatively peaceful yet problematic rule of the Tokugawa shogunate. This likely influenced his approach to the Musashi saga, which depicts the aftermath of war on a human scale: duels between two men or small battles where Musashi, acting as a one-man army, tackles enemies that should have overwhelmed him. While the Bushido code is portrayed, it’s never glorified as it is in many chambara. In fact, the film seems to condemn it as an excuse for ruthlessness—an empty pursuit that improves neither society nor the individual. While there’s some visceral damage, the violence acts as succinct punctuation within the fragmented melodrama. However, such themes are never quite as elegantly explored as they would be in Kihachi Okamoto’s The Sword of Doom (1966).

As a hired blade and instructor, the historical Miyamoto Musashi survived regime changes during a period of intense political turmoil, as the Tokugawa clan fought to re-establish a supreme shogunate that would rule Japan for over two and a half centuries. As allegiances shifted, Musashi made many enemies, maintaining an austere existence until his remaining rivals were defeated.

In his later years, he withdrew entirely, living as a hermit in a cave to focus on painting, calligraphy, and his two major literary works. Go Rin No Sho / The Book of Five Rings detailed his teachings on strategy and swordsmanship, while Dokkōdō / The Solitary Path offered a stark philosophy of self-discipline. Undefeated throughout his life, Musashi achieved a rare distinction for a samurai of that era: he died peacefully of natural causes. Unsurprisingly, the film doesn’t cover this long, tranquil final chapter.

JAPAN | 1965 | 121 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Tomu Uchida.

writers: Narusawa Masahige & Suzuki Naoyuki (Part I); Suzuki Naoyuki & Tomu Uchida (Parts II-V). (Adapted from the novel by Eiji Yoshikawa).

starring: Kinnosuke Nakamura, Wakaba Irie, Isao Kimura, Satomi Oka, Chieko Naniwa, Ken Takakura, Rentarō Mikuni, Michio Kogure & Shinjirō Ebara.