THE FALL OF AKO CASTLE (1978)

Based on Japanese 18th-century events, this is the tale of the Asano clan's downfall and the revenge of its former samurai on the perpetrator of the catastrophe.

Based on Japanese 18th-century events, this is the tale of the Asano clan's downfall and the revenge of its former samurai on the perpetrator of the catastrophe.

The Fall of Akō Castle / Akô-jô danzetsu is among the most important, and gorgeous, historical epics of Japan’s rich cinema heritage. With this new high-definition restoration by Toei studios, scanned from original film elements, it takes its well-deserved place in Eureka Entertainment’s ongoing ‘Masters of Cinema’ imprint of boutique Blu-ray releases.

It’s a perfectly paced, serious samurai movie based on what happened during the first years of the 18th-century. The story’s become Japan’s most well-known and retold; though stemming from real events, it’s been repeatedly reimagined and embellished in too many versions to count. Among these adaptations, director Kinji Fukasaku’s rendition is often cited as the most accurate portrayal of the now legendary tale. Drawing upon verified historical details, Kôji Takada’s measured screenplay extrapolates the probable connecting events, utilising the intricate human dynamics to propel the narrative with clarity and a poetic license that imbues tragedy with beauty.

I won’t spend too long recapping the story and sorting out fact from fiction, as this is covered more than enough on the few, somewhat repetitive extras accompanying this immaculate print. In Japan the story is commonly known as 赤穂事件, Akō jiken—which simply means The Akō Incident and sometimes as 四十七士, Shijūshichishi—translated as The 47 Rōnin, a title perhaps more familiar to international audiences.

Most of the Genroku Era had been peaceful and prosperous under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate governing a realm of fiefdoms, each controlled by a feudal lord or Daimyō. However, during the 13th year of Genroku, which equates with CE 1700, that economic stability began to falter with power dynamics rapidly shifting. There was a trend for lesser clans to be dissolved, and their territories and assets placed under the control of neighbouring Daimyō. The rich and powerful were becoming yet richer and gaining greater influence over decision-making, and that sort of thing always sows dissension.

During the titles of The Fall of Akō Castle (also known as Swords of Vengeance), we’re told that 48 Clan Houses fell under the dictatorship of the fifth Tokugawa Shogun, leading to around 30,000 samurai losing their masters. In other words, they were suddenly made rōnin—basically freelance mercenaries with samurai training.

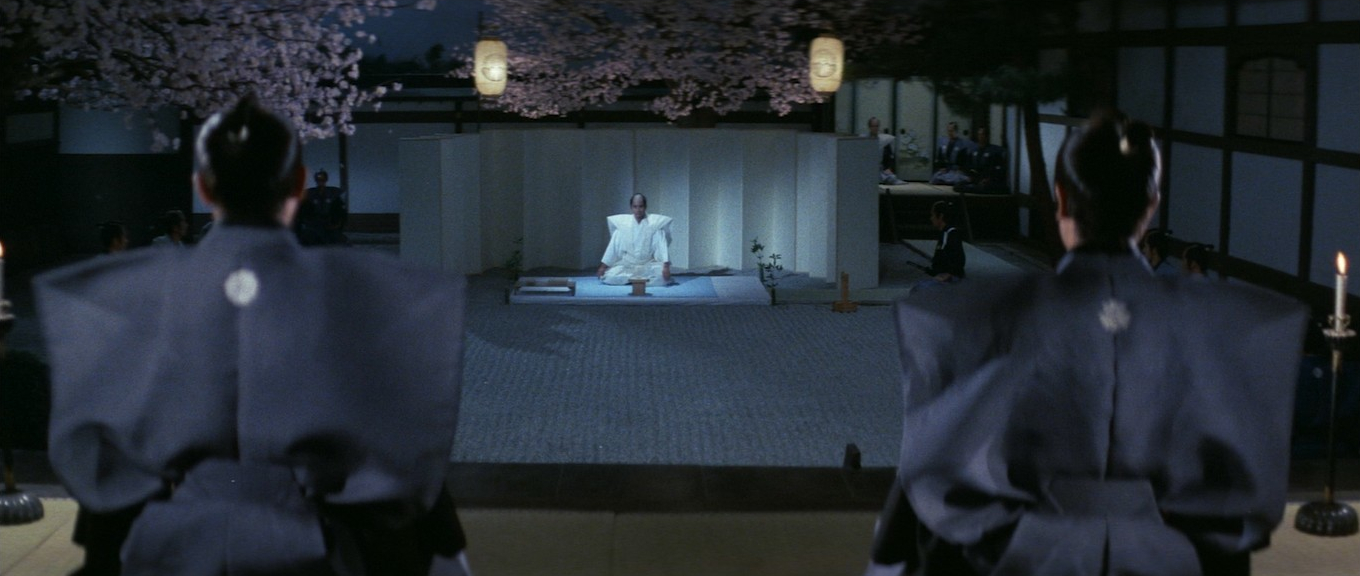

The film opens with the rhythm of silk dragging across tatami mats as officials assemble in preparation for the arrival of Emperor Higashiyama’s Envoys. This sound of mannered elegance will be mirrored during the film’s climatic scenes by the sound of determined footfalls on fresh crisp snow as a band of samurai march through deserted streets to exact ‘righteous vengeance’ for the events we see transpire in the first few minutes.

Among the gathering dignitaries is Lord Asano Naganori (Teruhiko Saigō) of Akō Castle who’s been invited to the Shogun’s Edo Castle to assist Lord Kira Yoshinaka (Nobuo Kaneko) with arrangements for the ceremonial reception of the imperial envoys. It seems there was already bad blood between these two lords and Kira apparently bears a grudge and repeatedly disrespects and insults Asano in public, relying on the rule that no weapon may be used in the Corridor of Pines, where they have gathered. However, Asano’s demeanour of Confucian calm gives way to momentary ire—he draws his dagger, slashing the older official. Although both men have breached the samurai code (merely insulting a fellow lord was a serious offence), Kira protests his innocence, maintaining he did nothing to provoke Asano who just went crazy for no reason. As a result, Kira is found blameless, but Asano is ordered to commit seppuku—ritual suicide.

When news reaches Akō Castle, Asano’s subjects are outraged and, knowing their Lord wasn’t given to such rash outbursts, reject this verdict as unjust. His chamberlain and chief samurai, Ōishi Kuranosuke Yoshio (Kinnosuke Nakamura) convinces the household not to make a stand there and then, instead feigning acquiescence to the shogunate and vacating the castle. But not before convincing a contingency of Asano’s loyal retainers to sign a declaration of allegiance and thus setting in motion his long-game vendetta that forms the film’s central narrative.

For nearly two years, the rōnin of Akō Castle appear to lead the mundane lives of civilians. Ōishi divorces his wife, Riku (Mariko Okada) and disowns his family, embracing a dissolute lifestyle in the Geisha houses of Kyoto where he’s seen to surrender to the excesses of alcohol and gambling. This is but a ruse to protect his family from being implicated in his plotting. Also, he hopes that Lord Kira’s fears of reprisal will fade, and he’ll drop his guard or simply tire of the expense of additional bodyguards and hired spies.

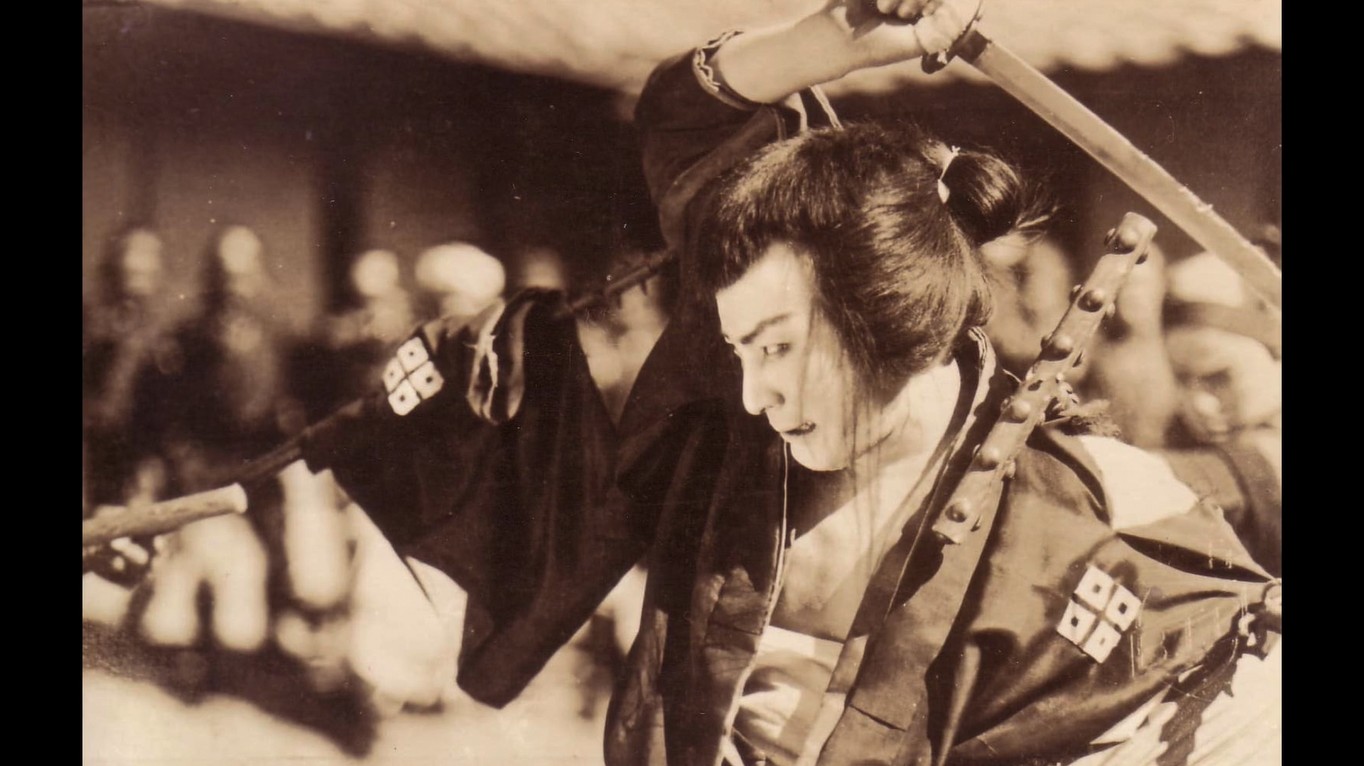

To help deal with those spies and assassins sent by Kira, Ōishi keeps an experienced rōnin, Fuwa Kazuemon Masatane (Sonny Chiba) close by. Although he dresses in peasant gear and looks like a wild man, he’s a formidable and fearless swordsman, which he proves on several occasions in tightly executed fight scenes, often in confined spaces where decorated screens, paper panels, and other architectural features help or hinder the opponents.

While waiting for things to cool off, Ōishi also petitions the government to reopen an inquiry into the assault and investigate Kira’s part in it more fully, if only taking statements from those who witnessed the events. He’s also biding his time to see what becomes of the Asano Clan’s fiefdom, whether it’s passed to Asano’s younger brother, and recognised heir, or not. It seems he wants to give the government every chance to redress the iniquity, so that when he and his disparate band of 47 rōnin take action, it will be seen as justified—honourable, even if technically treasonous.

The treatment of the various codes and honour-bound behaviour is subtle and complex, but we also see the people as real emotional beings under this ritualised public pretence. All the cast come across as historically authentic but remain accessible and understandable to an audience of today.

Kinnosuke Nakamura stands out in the lead role with a meticulous, stoically restrained yet multi-faceted performance as Ōishi. He was already into the third decade of a prolific career, which included Rōnin of Akō (1961), one of many earlier versions of the story. He was well known for starring as Ittô Ogami in all three seasons of the television series Lone Wolf and Cub (1973-76)—a role he would reprise for Fugitive Samurai (1984). And he’d just worked with director Kinji Fukasaku and co-stars Sonny Chiba and Nobuo Kaneko on Yagyu Clan Conspiracy (1978). Fukasaku, Chiba, and Nakamura would also reunite for the popular television series of the same name (1978-79).

For Fukasaku, The Yagyu Clan Conspiracy was a welcome departure after a run of hugely successful yakuza movies that comprise the Battles Without Honor and Humanity pentalogy—notorious for their brutal, gritty, almost verité style—which also starred Nobuo Kaneko in the recurring role of the gangland patriarch. By then, Fukasaku was synonymous with Japan’s gangster genre, but the success of his first venture into the samurai jidaigeki genre had led to Toei putting him in charge of their annual flagship film to be presented at arts and film festivals, choosing the popular story of the ‘Akō Incident’ as its source material. The result is far more restrained and poetic than would’ve been expected, closer to some epic Shakespearian tragedy that might’ve come from Akira Kurasawa.

The Fall of Akō Castle is a visual treat throughout, due in no small part to Fukasaku’s favourite cinematographer, Yoshio Miyajima—who was also responsible for one of the most beautiful films of all: Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964). Here, Hanjirô Nakazawa also lends a hand. A shout-out has to go to background artist, Saburo Nishimura and the production team who ensure crucial period details are accurate but also provide an integrated commentary on the narrative itself. For example, as one of the impatient rōnin loses his pride and falls upon hard times, unable to care for his young wife and baby, the paper in the windows of their shack is replaced with recycled scraps and the squares filling the window are fragments of printed notices or packaging.

Many of the sets directly reference famous woodblock prints of the events and environs, most of which would’ve been familiar to Japanese viewers with any interest in the story. Fukasaku makes good use of the decoration and parallel lines offered by the floor matting, free-standing screens, and sliding panel walls. These rigid grids seem to flatten some compositions in much the same way as the distinctive ukiyo-e style art of Edo period Japan. He takes every opportunity to exploit the strong symmetry to emphasisie the inflexible social structures that govern the characters, almost like a game of behavioural chess where even subtle gestures or phrases elicit predictable and prescribed responses. As these established norms are challenged, the figures increasingly bring chaos to the compositions and roving cameras skew the perfect balance. Rarely is setting used so eloquently to deliver important subtext.

The Fall of Akō Castle is an excellent primer in an important historical and cultural event and essential viewing for any fans of the samurai genre for which it provides a benchmark. It’s as mannered and deliberately paced as an art movie, yet it doesn’t disappoint in terms of action. The final battle is as well-choreographed and visceral as any, with Sonny Chiba convincingly demonstrating Fuwa’s renowned sword skills in a prolonged, adrenaline-fuelled fight with Kira’s chief samurai, Heihachiro Kobayashi (Tsunehiko Watase)… and also keep an eye out for a couple of cameos from Toshirô Mifune as Lord Kira’s upstanding neighbour.

Fukasaku would go on to make several notable additions to the jidaigeki and chambara genres, including the highly entertaining supernatural take on the Yagyu Clad mythos, Samurai Reincarnation (1981) and another reworking of the Akō Incident with Crest of Betrayal / Chûshingura gaiden: Yotsuya Kaidan (1994). Today, though, he’s more often associated with Battle Royale (2000) his final feature that ignited the so-called Asia Extreme genre.

JAPAN | 1978 | 159 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | JAPANESE

director: Kinji Fukasaku.

writer: Koji Takada.

starring: Sonny Chiba, Hiroki Matsukata, Teruhiko Saigō, Tsunehiko Watase, Tetsuro Tamba, Yoshiko Mita, Mariko Okada & Toshirō Mifune.