TOY STORY (1995)

A cowboy doll is profoundly jealous when a new spaceman action figure supplants him as the top toy in a boy's bedroom.

A cowboy doll is profoundly jealous when a new spaceman action figure supplants him as the top toy in a boy's bedroom.

It’s hard to imagine, in this age of countless CG-animated movies, that only 30 years ago the world had never seen a full-length movie completely animated using computer. Audiences had seen byte-sized (pun intended) pieces of what digital graphics could do—brief digital sequences in films like Tron (1982), Young Sherlock Holmes (1985), or The Abyss (1989)—but to make a whole movie? It was unthinkable.

However, as we all now know, not only did those clever people at Pixar manage to pull it off, they did it with such style and wit that Toy Story was just the first in a long line of hugely successful, groundbreaking family movies that have entertained audiences around the world for decades. Despite the cutting-edge technology that was used to bring this new form of animation to life, the other key factor behind the studio’s success (which still applies today) is their philosophy of getting the main plot points and characters properly developed before even one computer artist enters the creative process.

Talking of plot, the film follows Woody, a cowboy doll who has spent his entire life as Andy’s favourite toy. Alongside Woody, there’s a whole host of other toys that all populate this small domestic universe: the main players being Mr Potato Head, Slinky the dog, Rex the tyrannosaur, Hamm the piggy bank, and Bo Peep, the porcelain doll.

Everything changes when Andy gets a flashy new space-ranger action figure for his birthday: Buzz Lightyear. Buzz is loaded with gadgets, comes in a spaceship-shaped box, but unlike his companions, has no idea he’s a toy. Woody, consumed by jealousy and fear of being replaced, accidentally knocks Buzz out of a window. The rest of the movie follows Woody’s desperate attempt to rescue Buzz, earn back the trust of the other toys, and escape the clutches of the local toy-torturer Sid before making it back to Andy’s in time for the big day of moving house.

To all those who haven’t seen it yet (where have you been?), if you think the story sounds a bit daft on paper, then trust me, watching Toy Story makes for a thoroughly enjoyable viewing experience, and it’s aged remarkably well. Its core concept of toys coming to life when humans are not around is both staggeringly simple yet also incredibly smart because we all owned toys when we were children; therefore, this genius idea can be imagined by everyone. It’s universal; it speaks to the child inside all of us. However, before I delve further into the film itself, I think a quick look at the studio’s origins is in order.

Pixar first started out as a division of Lucasfilm’s computer graphics department in the late 1970s—back then it was simply called Graphics Group. At this stage, the various people involved were just experimenting with what they had at their disposal. Then, in 1986, tech pioneer Steve Jobs, who’d just been forced out from Apple, got on board and became the majority shareholder. Since the technology of the time wasn’t yet advanced enough to produce full-length animated films, the company initially concentrated on developing computer hardware until animation for feature films became viable.

Along with a new company, Jobs had also acquired some serious talent that had already been on board for years. Visionaries like Ed Catmull, Alvy Ray Smith, and later John Lasseter, were pushing the limits of what computer animation could do. Lasseter, a former Disney animator, was the main creative force determined to prove that digital animation could carry real emotion.

Throughout the 1980s, Pixar made short films to demonstrate its software’s capabilities. One of these, Luxo Jr. (1986), featuring a playful desk lamp, went on to become the company’s logo. Then in 1988, Lasseter produced the short film Tin Toy, which was told from the perspective of a toy, referencing Lasseter’s love of classic toys. Tin Toy won the 1989 Academy Award for ‘Best Animated Short Film’, the first computer-generated film to do so. Tin Toy caught Disney’s eye, and the new leadership—Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg—tried to reel John Lasseter back in. But Lasseter felt loyal to Steve Jobs and Pixar, telling Ed Catmull: “I can go to Disney and be a director, or I can stay here and make history.” Realising he couldn’t convince him, Katzenberg shifted gears and pushed for a production deal with Pixar instead.

Disney had always made movies in-house, but things loosened up after Tim Burton asked for the rights to The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) and Disney agreed to let him make it outside the studio. This ultimately paved the way for how the two studios would work together: Disney would own Pixar, taking care of distribution and marketing, but they allowed Pixar to still operate with a significant degree of creative autonomy, while also maintaining their own distinct studio culture and creative development process.

Like any film in production, Toy Story went through a lengthy writing process before the final script was locked in and ready to go. Interestingly, an early draft featured Woody as a cynical, mean-spirited character. He would constantly put down the other toys, referring to Mr Potato Head as “Spuds-for-brains” and Slinky as “Spring Weiner”. This was because Katzenberg wanted the feature to be edgy and appeal to adults as well as children. Test screenings were so disastrous that Disney shut down production entirely until Pixar could rework the script.

Approximately three months later, the extensive writing team, including Joss Whedon (Buffy the Vampire Slayer), Andrew Stanton (Wall-E) and Pete Docter (Inside Out), managed to write up what was to become the final screenplay. Ultimately, it’s a “buddy movie,” and some of the films that the creative team used as an inspiration were Midnight Run (1988) and The Odd Couple (1968), with its main players starting off not really liking each other, but over time becoming strong friends. Okay, it might not be a completely original idea, but done right it always proves to be a winning formula—and with this, the Pixar people had really nailed it.

Of course, a big part of the film’s winning appeal is all down to the voices behind the toys, and the cast that signed on were some of the best in the business. To kick things off, getting Tom Hanks on board to play Woody was quite possibly one of the smartest creative choices the studio ever made. As big as Hanks is now, back in the mid-’90s, Hanks’ career trajectory was through the roof. He’d recently won two Best Actor Academy Awards for Philadelphia (1993) and Forrest Gump (1994), and, just prior to Toy Story’s 1995 release, had starred in one of the biggest commercial and critical hits of that year with Ron Howard’s masterpiece Apollo 13.

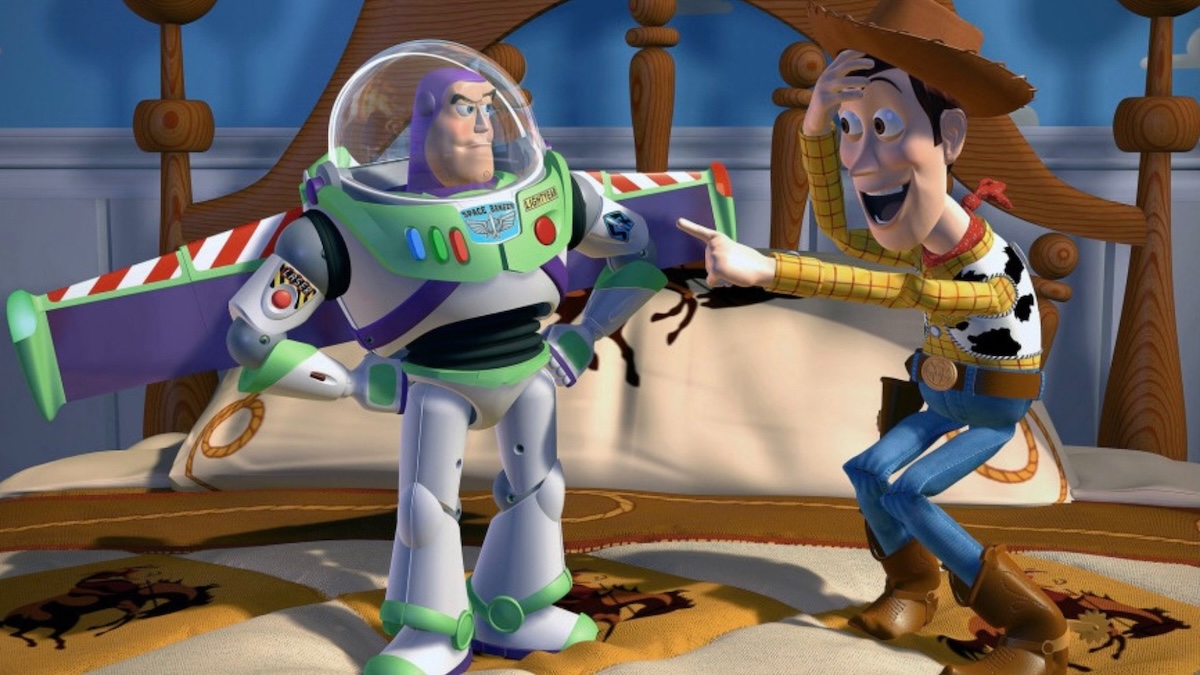

Now, we all know that Hanks is a wonderful screen actor, so it’s not exactly shocking to find out here that his acting behind the camera is just as impressive. He somehow makes Woody look, sound—and feel—completely real. Maybe it’s down to the perfect combination of quality VFX and writing, or to put it another way, good old-fashioned movie magic, but there’s an actual sense of warmth and vulnerability shining through those pixels, and seeing how he interacts with Buzz Lightyear is like watching a comedy double-act at times. Considering that Tim Allen plays the space ranger toy, it’s no surprise to see how well the humour lands throughout.

Before Allen rose to fame on the hit sitcom Home Improvement (1991-99), he was a stand-up comic for several years, so Allen going up against Hanks, who’d also had a lot of experience working with comedy in many of his earlier films, was pretty much the biggest dream team one could imagine. Allen’s acting is also on point: from the off he brings a fun mix of dumb over-confidence, regret, sadness—but most of all, just a sheer amount of joy.

The supporting cast are also great in their respective roles. For starters there’s legendary comedian Don Rickles as the somewhat blunt Mr Potato Head, Wallace Shawn (The Princess Bride) as anxious dinosaur Rex, Annie Potts (Ghostbusters) as the flirtatious Bo Peep, John Ratzenberger (Cheers) as the sarcastic Hamm, and last but not least Jim Varney (Ernest Goes to Camp) brings his own distinctive Southern accent and charm to Slinky the dog.

With all this abundance of comedy talent, it’s easy to see why Toy Story ended up being so hilarious; from frame one right through to the closing credits, the humour is relentless. For instance: a conversation has started about Buzz’s ‘deadly’ laser, with most of the toy collective being very impressed. Woody rightly states that it’s just a little light bulb that blinks, to which Hamm says with a knowing wink: “Laser envy!”

But it’s not only the dialogue that strikes a comedic note; there’s a ton of visual gags too: the string of monkeys that are poured out of a plastic barrel case to try and create a rope comes to mind, made even funnier when you hear their simian-like noises as they make their descent. The scenes with the toy soldiers are also hilarious—with a clever riff on the typical war movie trope occurring when one of them is trodden on and he tells the others to leave him behind, but Sergeant refuses, saying: “A good soldier never leaves a man behind.” And for film buffs everywhere, see if you can spot the reference to a particular Stanley Kubrick horror film during the scenes inside toy-torturing Sid’s house…

It’s fair to say that, watching Toy Story today, a few of the computer-animated characters look a little clunky; a dog’s lifeless eyes is one example, but when you consider what the technology back then was capable of, with each animator’s workstation only having an average 64MB of memory, and the rendering “farm” of PCs boasting 192MB and 384MB of RAM per machine (comprising of 800,000 machine hours and 114,240 frames of animation in total), it’s still hugely impressive to think that every single thing Pixar did during production: lighting, shading, motion, texturing, was being done at feature length for the first time.

The end result is a world that feels tactile, colourful, and surprisingly lived in. My favourite VFX are the small nuances like the way the light changes depending on what time of day it is, the stars shimmering at night, or a brief reflection on a Christmas tree bauble; these images still stand up three decades later, and are testament to the incredible skill and artistry that was used in this production.

When Toy Story hit US cinemas in late-1995, both critics and the public went crazy for it. Against a $30M budget, it cleared over $400M worldwide and picked up the first-ever Academy Award nomination for ‘Best Original Screenplay’ for an animated feature. Randy Newman’s score and song “You’ve got a Friend in Me” were also nominated—with the only actual win coming in the form of a ‘Special Achievement’ Oscar.

What’s far more important than awards, though, is seeing how truly revolutionary Toy Story was. Nothing would be the same ever again. Computer animation was no longer a fancy idea in someone’s imagination; it was now reality, and it paved the way for exciting and innovative changes within the industry. Their main competitors, studios like DreamWorks (Shrek) and Blue Sky (Ice Age), only exist because of Pixar’s achievements.

Admittedly, animated films of today look far slicker than Woody and Buzz’s first adventure, but few manage to be as charming or witty. However, what makes Toy Story stand out is not just the jaw-dropping visuals or laugh-out-loud comedy, it’s what lies at the heart of the film: a seemingly simple tale about the power of friendship, and the brilliance of the script that blends heartfelt emotion with sharp, effortless humour. Truly unmissable.

USA | 1995 | 81 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: John Lasseter.

writers: Joss Whedon, Andrew Stanton, Joel Cohen & Alec Sokolow (story by John Lasseter, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton & Joe Ranft).

voices: Tom Hanks, Tim Allen, Annie Potts, John Ratzenberger, Don Rickles & Jim Varney.