THE LOST WORLD (1960)

An expedition of scientists and adventurers travel to the Amazonian jungle to verify a claim that dinosaurs still exist there.

An expedition of scientists and adventurers travel to the Amazonian jungle to verify a claim that dinosaurs still exist there.

Probably more famous than viewed these days, Irwin Allen’s The Lost World will, for many people, fall into the so-bad-it’s-good category. However, it’s not a bad movie, despite containing hilariously dated VFX, hammy performances, and a crude script and direction. And that’s because there’s unironic enthusiasm and humour carrying you along, keeping you interested in what’ll happen next, even as you chuckle at the absurdity of it all.

Based fairly closely on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel (albeit with a simplified plot and updated to the 1960s), The Lost World tells the tale of a team of explorers, led by Professor Challenger (Claude Rains), venturing deep into the Amazon Basin in search of a remote plateau reputedly inhabited by dinosaurs.

Once early scenes in London where Challenger recruits volunteers for his expedition are over, the film takes place on (or inside) the mysterious plateau. This allows Allen and his co-writer Charles Bennett to extract maximum atmosphere from their exotic location (which they achieved despite some clunkiness), and to build drama from the group dynamics (which they’re less successful at, but it has its moments).

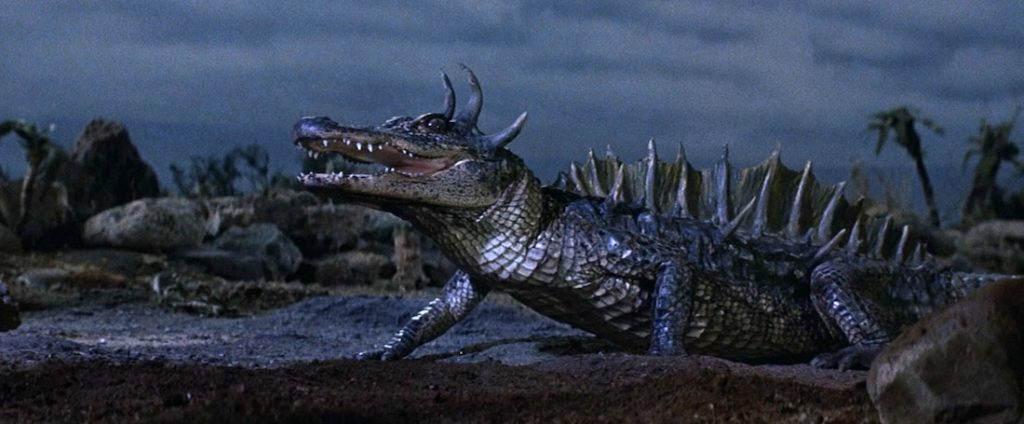

The plateau is full of threatening wonders (carnivorous plants, trees that strangle you, spider webs the size of houses), but it’s the dinosaurs that are best remembered, despite not appearing too often. They’re also just real animals in rudimentary disguises (like an iguana with glued-on horns), or reptiles like alligators and monitor lizards shot to appear far larger.

All of the creatures are risibly unconvincing post-Jurassic Park (1993), but it’s still possible to imagine their effectiveness to a ’60s audience that didn’t expect verisimilitude. A generally lukewarm review by A.H Weiler in The New York Times, for example, was impressed enough with the beasts, saying that “[the cast] and the artificial plot are no competition for the prehistoric monsters and lush tropical and volcanic backgrounds”.

Allen had reportedly wanted to use stop-motion puppets rather than live animals for the dinosaurs. He has previously worked with the legendary Ray Harryhausen on a highly-regarded dinosaur sequence in a documentary called The Animal World (1956), but the $1.5M budget for The Lost World wouldn’t stretch to it.

As it stands, the animals are better actors than most of the humans. The only performer who truly shines is Claude Rains, a revered Hollywood star since the 1930s and a multiple Academy Award nominee. 71 at the time, he seems determined to have fun and steals scenes every time he opens his mouth. His character, Challenger, is described by a reporter as “that indomitable zoological professor” and Rains plays this indomitability to the hilt—whether wielding his umbrella as a weapon or declaring “there will be no women on my expedition!” (An insistence in which he’ll be proven wrong). And there are glimpses of the classic era Rains, too, who appeared in Casablanca (1942) and Notorious (1946). Despite The Lost World’s silliness and Challenger’s suspiciously fake-looking ginger hair, Rains is a magnetic presence.

In fact, nobody else in the cast can compare to Claude Rains, although Richard Haydn savours moments of wry humour as another professor, and Jill St. John (the token silly woman who arrives for an Amazonian expedition wearing pink boots, with a poodle called Frosty), comes closest to rivalling Rains. At least there’s a sense her character is a real person, unlike the local Venezuelan guide Costa (Jay Novello), who’s an amalgam of Manuel from Fawlty Towers and a ‘cowardly foreigner’ cliché. Similarly uninspiring is the expedition’s pilot, Gomez (Fernando Lamas), whose two functions are to resent Lord John Roxton (Michael Rennie) and to always play the guitar to add some foreign atmosphere. Somehow even less credible than those is the utterly wooden Malone (David Hedison), the film’s romantic lead.

Just as lumbering as most of the performances is the dialogue and direction—which is surprising coming from Allen, as he’d progress to classics like The Poseidon Adventure (1972) and The Towering Inferno (1974) just over a decade later. A shot of a wrecked helicopter is accompanied by the line “oh no, the helicopter’s wrecked!” Early on, another scene that depicts a learned society’s meeting in London (where Challenger presents to fellow scientists his conviction that dinosaurs still live), is stagey in the worst possible way. Two of the main characters are literally on a stage throughout and hardly anybody moves at all.

There’s a certain slapdashness to The Lost World, too. For example, more than once, Roxton speaks of darkness and moonlight when the set is lit as bright as day. Also, a poisonous mist moves through a cavern seemingly both uphill and downhill, in a way that’s clearly not possible.

But there are occasional touches of directorial verve from Allen, like a helicopter sequence when the party first approach the plateau. It cuts back and forth from awesome landscapes to different individual faces seen through the craft’s windows. On the big screen, in CinemaScope, I’m sure this must have been breathtaking back in 1960.

Less impressive to modern audiences will be The Lost World’s outdated attitude toward women. It’s the kind of film where the men discuss “the female of the species” and non-Europeans in poor terms. A native girl, predictably clad in a tiny skirt, is treated like an animal or specimen by the white men. Challenger even refers to her as a “creature”. But given the time this movie was made, with its backwards-looking Boy’s Own values and unsubtle nature, it would be unrealistic to expect anything different.

For those who do want a more contemporary take on the story, several other adaptations of The Lost World appeared in 1992, 1998, 1991, and 2001…. none of them making much impact. There had already been a 1925 version made with Wallace Beery playing Challenger, too. The Lost World’s greater legacy, of the novel at least, was its loose inspiration for Jurassic Park (which even had a sequel named after it)… although The Lost City of Z (2016) is also worthy of note, as it was based on the life of British geographer and archaeologist Percy Fawcett, whose life helped inspire the novel.

Allen’s 1960 movie, despite its many flaws, remains the best-known of the many versions. Innovations can date terribly, of course, and in trying to present a lavish spectacle with cutting-edge VFX it seems far more old-fashioned than more modest productions filmed a decade or two earlier. But even if its VFX are downright Jurassic and its drama leaden, The Lost World still holds audience attention as a piece of straightforward hokum, enlivened by a mischievous performance from Claude Rains.

USA | 1960 | 97 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Irwin Alen.

writers: Irwin Allen & Charles Bennett (based on the novel by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle).

starring: Michael Rennie, Jill St. John, David Hedison, Claude Rains & Fernando Lamas.