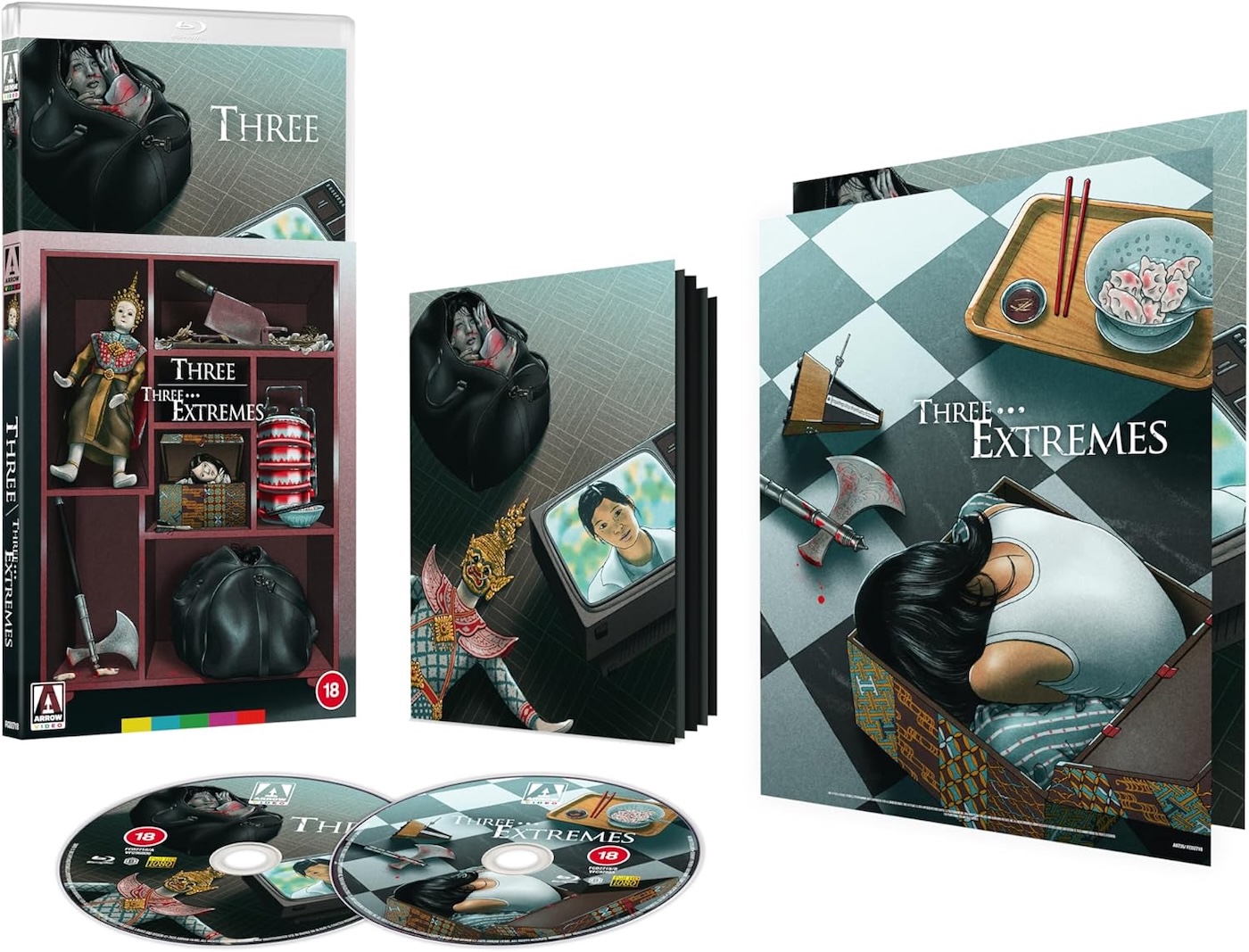

THREE / THREE… EXTREMES (2002-04)

A trio of ghostly tales of terror, each from a different country, form the anthologies Three and Three... Extremes.

A trio of ghostly tales of terror, each from a different country, form the anthologies Three and Three... Extremes.

At the dawn of the new millennium, these two feature-length portmanteau played a vital role in establishing the cinematic identity of the four South East Asian countries involved with this pan-national collaboration. So, it’s great that Arrow Video are releasing these splendid 2K restorations in a lovely Blu-ray package with some excellent extras… and just in time for Halloween. More than two decades after their initial release, and to varying extents, the six short films presented here remain fresh, intriguing, poignant, beautiful, transgressive and, above all, relevant.

The “Three” series was the brainchild of its producer, Peter Ho-Sun Chan, a hugely influential director, born in British Hong Kong, raised in Thailand, educated in the UK, and working across continents including making films in Hollywood. Having started out in the early-1980s as assistant director for the likes of Jackie Chan and John Woo, he would become the first to win all three ‘Best Director’ awards at the Hong Kong Film Awards, the Golden Horse Awards, and the China Golden Rooster Awards. His career spans an eventful period of Asian history, as the signing of the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration relinquished colonial control of Hong Kong and paved the way for its reabsorption into China by 1997. This changed the cultural dynamic of the entire Asian continent as Hong Kong’s dominance diminished and Hollywood encroached even more.

Chan saw an opportunity for Asian nations to assert their cultural identity while taking advantage of the massive market shift, perhaps learning how to better pool their skills and resources. He wanted to lead by example and so encourage collaboration between different countries, showcasing their cinema craft in the hope of exposing international audiences to foreign-language movies and thus creating wider distribution opportunities.

At the time, Japan had taken the lead with a distinctive genre now recognised as J-horror, following the surprise success of Hideo Nakata’s Ringu / The Ring (1998), Takashi Shimizu’s Ju-on / Ju-on: The Curse (2000), and Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Pulse (2001). It seemed natural to capitalise on this unexpected global interest and work within a related genre for the first trio of short films to be presented in Three (2002). The directors contributing the three short, self-contained films were South Korea’s Kim Jee-woon, Thailand’s Nonzee Nimibutr, and Peter Ho-Sun Chan himself.

While in production, Japanese cinema made another genre breakthrough with what would be branded Asia-extreme. At the vanguard were Takashi Miike’s Audition (1999), Kinji Fukasaku’s final film, Battle Royale (2000), Ryuhei Kitamura’s Versus (2000) and South Korea’s Park Chan-wook also making a notable contribution with Oldboy (2003). Though horror-related, Asia-extreme bravely blends other genres into intense psychological thrillers rife with sex, gore, cruelty and transgressive themes. Thus, the follow-up film in what Chan hoped would become an ongoing franchise was Three… Extremes (2004) and features contributions from both Takashi Miike and Park Chan-wook, with Hong Kong’s Fruit Chan stepping in as the third contributing director.

The portmanteau had been a genre staple since Dead of Night (1945) from Ealing Studios, well ahead of the format’s 1960s heyday with classics such as Roger Corman’s Tales of Terror (1962) and Amicus’ Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1965) directed by Freddie Francis which, incidentally, was in parallel production on the other side of the world with Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (1964)—the film that brought the portmanteau to mainstream Asian cinema. So, Chan felt it a natural choice to showcase genre films in this way, though he didn’t devise any cheesy framing story, which I feel is a bit of a shame, but he didn’t want such a contrived device to colour the approach of the various writers and directors. Each film was initially conceived without knowledge of what the adjacent tales would be, affording each creative team free rein.

The three segments are “Memories”, directed by South Korea’s Kim Jee-woon; “The Wheel”, directed by Nonzee Nimibutr from Thailand; and “Going Home”, made in Hong Kong and directed by Peter Ho-Sun Chan.

The Korean opening segment, “Memories”, begins with a familiar haunting in a modern setting. A man (Jeong Bo-seok) wakes on a sofa, sensing a presence in the darkened room. The scene slow-builds to a predictable yet well-executed jump-scare, which momentarily diverts viewer expectations. So, the pay-off that follows is an unexpected mood shift as we discern the hunched silhouette of a woman in the foreground. Of course, her face is obscured by a fall of long black hair—it is an Asian ghost story after all.

The man is in therapy for memory loss, unable to recall when or why his wife left him. His condition has developed into a dissociative disorder, suggesting trauma too profound to process. Meanwhile, a woman we presume to be the absent wife (Kim Hye-soo) awakens at the kerb side of a deserted road, surrounded by her scattered belongings—purse, watch, broken mobile phone… She consults her address book for a clue to her own identity before walking to a café and dialling her home number. No reply. The motif of broken lines of communication recurs throughout, alongside notions of emotional and spatial distance between the characters. The setting, a newly constructed but eerily vacant New Town, amplifies this sense of isolation.

Her disorientation recalls the amnesiac wanderings of characters in films like Satoshi Kon’s anime Perfect Blue (1997) or the fractured Lynchian fugue states of Lost Highway (1997) and Mulholland Drive (2001). Citing David Lynch as an influence, cinematographer Hong Kyung-pyo uses lots of deep darkness and wide-angle compositions to emphasisethe emptiness of these spaces. Brutalist tower blocks, wide empty roads, and sparsely furnished interiors evoke a kind of neo-Gothic dread, where urban alienation becomes a conduit for supernatural intrusion.

The clean, concrete order of the new build may seem to offer shelter but ultimately fails to protect the characters from their existential unease. I am reminded of a quote by philosophical geographer, Yi-Fu Tuan, “In a sense, every human construction, whether mental or material, is a component in a landscape of fear because it exists in constant chaos…”

The narrative unfolds like a subdued sleuth story, with both protagonists trying to piece together past events while suffering from memory loss and haunted by disturbing visions. These may be fragments of suppressed trauma or manifestations of a supernatural presence. There’s some effectively disturbing and memorable imagery along with a healthy dose of ambiguity. But it’s pretty clear from the outset that one of them is already a ghost navigating a purgatorial space in search of resolution. This places Memories within a specific sub-genre of ghost stories—those concerned less with terror than with metaphysical reckoning, such as Mario Bava’s Lisa and the Devil (1974), Lewis Gilbert’s Haunted (1995), and M. Night Shyamalan’s The Sixth Sense (1999), which explore similar boundary-blurring hauntings.

Foreshadowing is a key narrative device and a staple of effective horror. Here, though, some familiar tropes are a little on the nose. Less than five minutes into the 40-minute duration, I had guessed the shock reveal that director Kim Jee-woon holds back for the dénouement. Yet this may well be intentional—perhaps we are meant to intuit something about the protagonists that they themselves cannot grasp. It’s certainly not a problem, as both the leads are eminently watchable, compelling and emotionally resonant, which is crucial given the film’s reliance on visual storytelling and minimal dialogue.

At times, the segment feels like a calling card—a polished showreel from a young director eager to impress and land a feature deal. Indeed, this is an early career offering from Kim Jee-woon, whose debut feature The Quiet Family (1998) blended black comedy and horror with deft precision and garnered acclaim on the festival circuit. He was poised to make his third breakout feature—the excellent psychological thriller, A Tale of Two Sisters (2003).

The second segment offers a contrast with something refreshingly different. Nonzee Nimibutr’s “The Wheel” may feature possessed puppets—admittedly a creepy horror staple—yet avoids direct comparison with the likes of The Puppet Master franchise or the ventriloquist dummy segment in Dead of Night. The puppets here are beautiful hoon krabok—large, lavishly crafted puppets operated from below with long rods. Featuring a troupe of Khon dancers and puppeteers, the tale could not be more quintessentially Thai, as the art form is now recognised by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Though we learn that the social standing of such itinerant troupes is low and at odds with the high esteem reserved for the Hun Lakorn Lek—troupes with an almost identical set-up and similar repertoire performing for royalty and the elite class.

After falling ill, Puppet Master Tao (Komgrich Yuttiyong) sent his wife and son out into a nearby lake, at night, to drown his puppets. Apparently, he blames his illness on the hoon krabok, which he believes to be cursed. The folklore surrounding the puppets tells that if they are procured through nefarious means, they will visit upon their new ownerthe same fate that befell their rightful master. His wife and son are lost along with the two puppets but reappear as ghosts perched on the roof beams of his home, and Master Tao dies in a fierce fire that seems to have started in his imagination. The Khon dance trainer, Master Tong (Pongsanart Vinsiri), sets his mind upon recovering the valuable puppets and becoming the master over the entire troupe.

Of course, the karmic wheel turns, and he seems destined to suffer a similar fate, but not before the malign supernatural influence of the cursed puppets brings out the lust, greed and jealousy of those around them. Rivalry ignites and escalates between our young puppeteer protagonist Gaan (Suwinit Panjamawat) and Khon trainee Plew (Pornchai Chuvanon) for the affections of Nuan (Kanyavae Chatiawaipreacha), and young Bua falls increasingly under the thrall of the puppets’ aura until she fulfils the trope of the possessed child—her innocence and trusting nature eventually becoming the vehicle for evil.

The distinctive aspects of culture and regional folklore are the strengths of this middle segment, with a capable cast and some painterly cinematography by Nattawut Kittikhun, who is not afraid to push the limitations of the film stock in low light, to allow blurring that implies ruptures in material reality. However, the storytelling is a little cluttered and unclear and feels like it really needed more time to flesh out the characters and tell its tale with any real depth. Conversely, as indicated by the final scenes, it may simply fall into cliché if extended.

Saving the best until last, Peter Ho-Sun Chan’s “Going Home” is the strongest and most interesting of the first trio. After a brief and rather enigmatic opening scene set in an old-style photography shop, which will only make sense much later, we meet Chan (Eric Tsang) and his young son Cheung (Li Ting-Fung), arriving at a run-down apartment block. It seems there are only two other occupied flats—one belonging to the rather dour caretaker (Ting Tak-Ming) and the other to Yu (Leon Lai) and his wife Hai’er (Eugenia Yuan), who requires a wheelchair, which begs the question why all their homes are not on the lower floors. We learn that the whole block is scheduled for demolition, so one assumes the majority of the flats have already been stripped of amenities.

The location was the former Police Married Quarters in the Sheung Wan district of Hong Kong, which is appropriate, as we learn that Chan is a police officer. Cheung, intimidated by all the empty rooms, is too scared to venture far while his father is at work, until a young, silent girl in a red coat, who we may recall from the photography shop, befriends him and coaxes him out to play. One day, though, when Chan returns home, Cheung is missing.

Having assumed the little girl was the daughter of Yu and Hai’er, he goes to their apartment to collect his son, but Yu states that they have no children. His suspicion aroused, Chan returns when Yu leaves, believing that Cheung could have been kidnapped. He does not find Cheung there, but discovers that Yu has murdered Hai’er and now tends to her corpse as if she still lives. But there is way more to it than first meets the eye. Yu returns, overpowers Chan and takes him captive. It’s a beautifully constructed conundrum: Chan must appease Yu to secure his release so he can go and search for Cheung. It turns out Hai’er has been clinically dead for some time, but Yu had a pact to use traditional Chinese medicine and folk magic to prevent her soul from leaving her body while the terminal cancer she had fades away. When it’s gone, she will revive. Or so he believes.

“Going Home” is beautifully crafted, with Christopher Doyle’s cinematography turning each shot into a striking composition—from sweeping cityscapes to the decaying interiors of abandoned rooms, where relics like furniture and photographs still linger. There was only one flaw that bothered me. A tragic misunderstanding could have been avoided if Yu had only taken time out to explain a little more—there was even video evidence that he neglected to use. Like the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet could have been averted if the message had gotten through to Romeo… the misunderstanding that the heart-rending ending hinges upon could have been avoided.

Despite this flaw in the plotting, Going Home is an exceptional tale of mystery and imagination with a central thread that borrows ideas explored by Edgar Allan Poe in his short stories like “The Premature Burial” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar,” plus a bonus ghost tale masterfully woven into the narrative, which, rather surprisingly, mitigates some of those tragic consequences. Original, absorbing, poetic, poignant, and genuinely haunting… I will be thinking of this one for a very long time to come.

SOUTH KOREA • THAILAND • HONG KONG | 2002 | 129 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | KOREAN • THAI • CANTONESE • MANDARIN

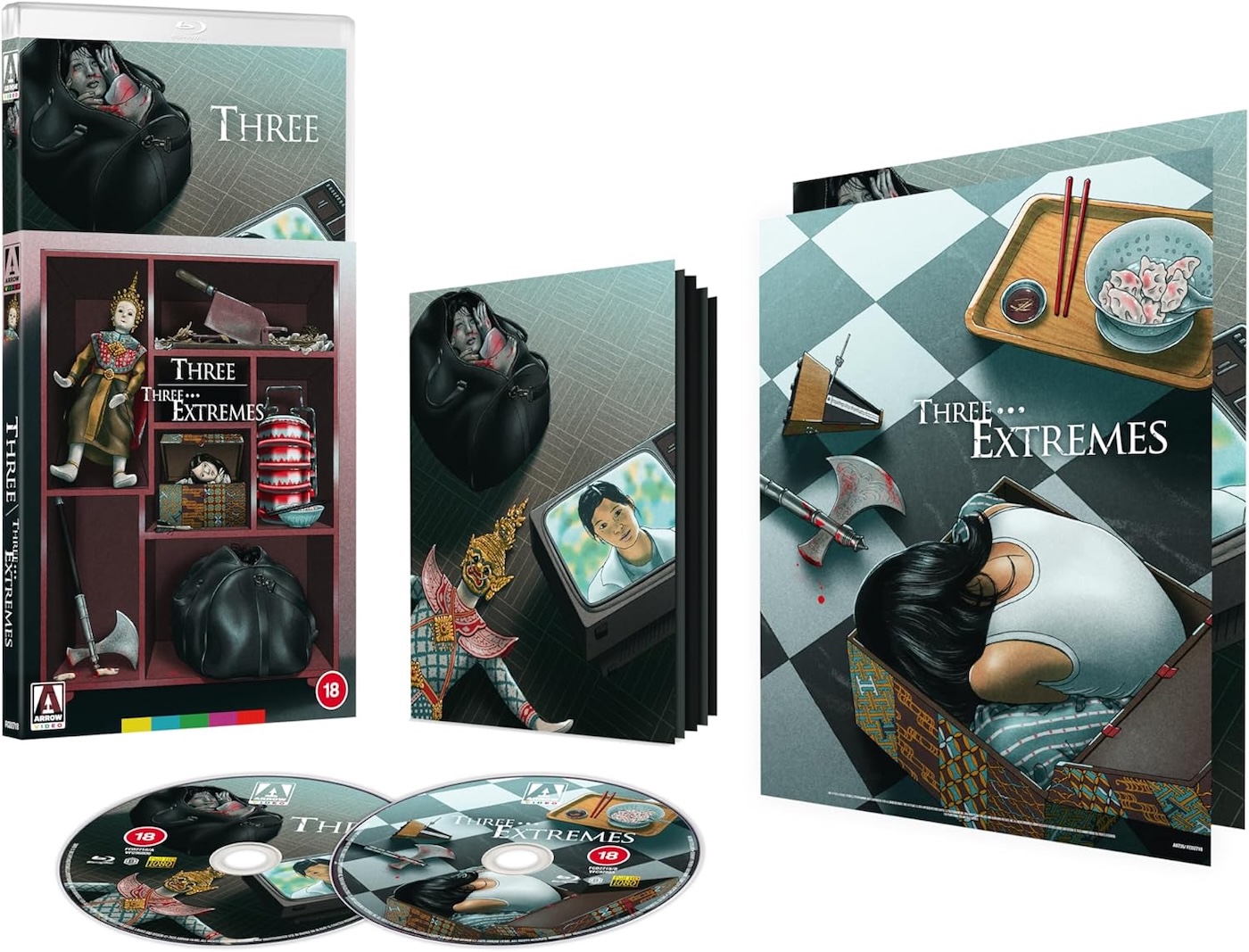

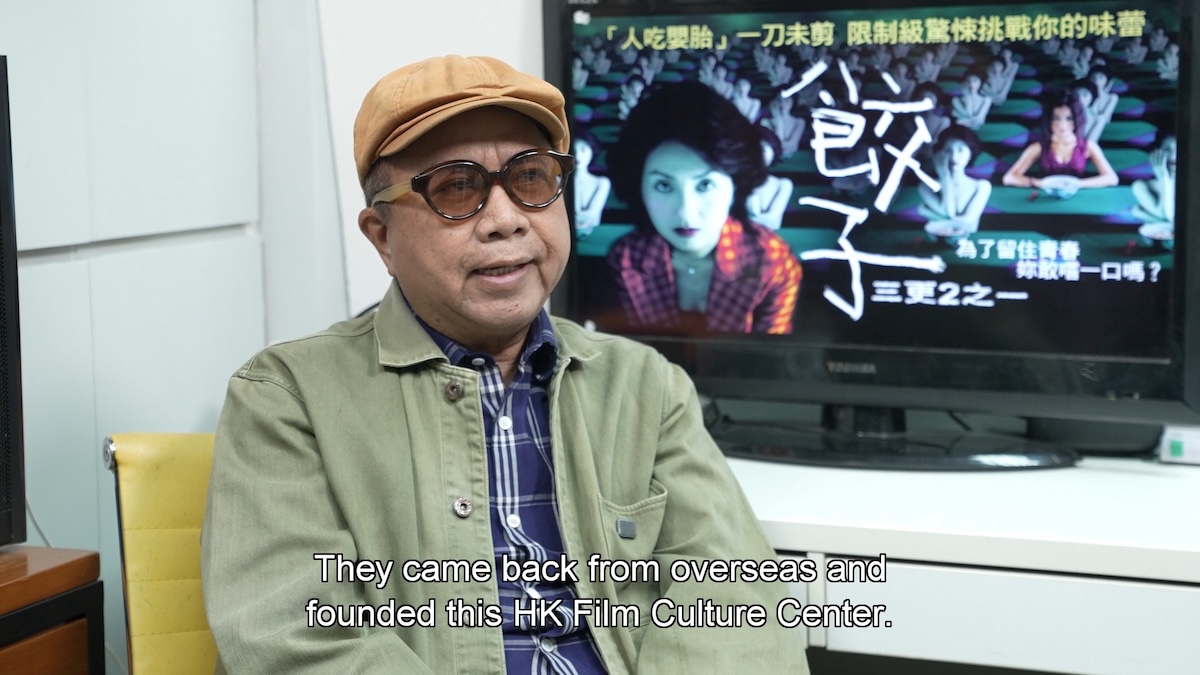

The three segments on this second outing are “Dumplings”, directed by Hong Kong’s Fruit Chan; “Cut”, directed by Park Chan-wook; and the outstanding “Box”, directed by J-Horror heavyweight, Takashi Miike…

Fruit Chan’s “Dumplings” is the audacious opener for this second three-film anthology, shot in the director’s native Hong Kong. It began with collaboration between the director and lead actress Miriam Yeung, who proposed several scripts before selecting this one. It seems she wanted to show off her acting when cast against type, as she was known for rom-coms and light dramas—which this is not. The script continued to develop even during production, as Fruit Chan responded to the energies between her and her co-star, Bai Ling. They all felt the characters needed further fleshing outand the narrative could be expanded with more backstory and richer subplots for the secondary characters. Indeed, they had a point. “Dumplings” was expanded and later released as a stand-alone feature. So, really what we are seeing here is a work in progress, and at times that is how it feels.

Li (Miriam Yeung) arrives at the apartment of Mei (Bai Ling) in a rather insalubrious part of the city where she stands out for her designer clothes and accessories. She’s there seeking dumplings that are apparently the best, and Mei has already begun preparing the magic meal, which promises to rejuvenate her. Now, it’s no spoiler when I say that there will be something sinister about those dumplings. In the first few minutes, we are clearly shown that the main ingredients are foetuses. Also, it transpires that Mei performs ‘backstreet’ abortions and regularly visits a clinic where she has an arrangement with one of the nurses.

Coincidentally, I had just been looking at “The Black Paintings” of Goya, the Spanish Baroque painter, while writing up my review of another transgressive movie, The Day of The Beast (1995). So, I quickly saw a clear parallel of the two women stealing and eating babies with the traditional tales of witches doing the same. Children being eaten or at risk of being eaten are a staple diet for myths and folklore, from the Roman God Saturn devouring his own children, to the witch who wants to eat Hansel and Gretel. There are even a few Biblical episodes involving child cannibalism. This aligns with other tales of witchery set against more contemporary backdrops such as Sidney Hayers’ Night of the Eagle (1962) Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby (1968) or even Ari Aster’s equally nauseating Hereditary (2018).

There is no denying that much of the content—some may say all of it—is distressing but it crosses so many lines, wallowing in the horror of disgust with such glee that one either has to look away or laugh. This very dark humour is deliberate, but at the same time it’s not shy about themes of incest and abortion—which it shows more than once, including a self-administered termination followed by fresh foetal cannibalism. It will trigger anyone with phobias of medical imagery and those who may have experienced related traumas.

Sometimes, it feels like Fruit Chan is trying a little too hard to be extreme, but in reality, it’s tamer than a lot of psycho-sexual imagery I had already seen in promo videos directed by Hiroyuki Kondo for Dir En Grey, the extreme visual kei J-Rock group. Dumplings depicts the horrific with a rather slick aesthetic or for comedic effect. There are shots of blood in water that are quite beautiful in purely visual terms, if removed from their context. And the scene where Li first overcomes her apprehension and disgust, chomping down on the dumplings with exaggerated relish while making eye contact with the camera, certainly can’t be taken seriously as it breaks the fourth wall. Bon appétit.

Those who’ve seen Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971) will, no doubt, remember the scene when Alex and his Droogs terrorise Mr. Alexander (Patrick Magee) and his wife (Adrienne Corri) in their home. The middle segment, “Cut”, directed by Park Chan-wook, is a sort of rehash, with no “in-out-in-out” but some proper “ultraviolence.” There is even a deranged dance routine that recalls Alex’s rendition of “Singing in the Rain”. Also, the action plays out in a neo-classical interior, which is obviously a set, resonating with the final scenes of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and is similarly shot with wide-angle lenses.

It’s a film about film, made on a film set, and celebrates this artifice right from the start with a scene of vampirism in a Gothic setting. But this is just there to wrong-foot the audience as the fourth wall breaks when the Director (Lee Byung-hun) calls “cut!” You know, I think I would have preferred to see that film instead of what we get.

None of the characters have names in this story, because they are not real people but ciphers serving a somewhat slim narrative. As the Director is leaving set, he’s accosted by an Extra (Im Won-hee). We may assume he has been doing stunt work, as he’s a big man dressed as a schoolgirl, though this is not necessarily the case. The Extra is disgruntled after being in the background for every one of the director’s movies, and he thinks it’s about time he landed a bigger role—perhaps something challenging like a psychopathic killer, he suggests.

The Director leaves the set and goes home. However, the film set he just left doubles as the interior of his lavish house where he’s knocked unconscious by a shadowy assailant who, of course, turns out to be the Extra. When the Director regains consciousness, he discovers that he’s bound and restrained by a long red cord that will not allow him to cross the room to where his Wife (Kang Hye-jung) is also bound to a stool at a grand piano by a network of taut piano wire, her fingers superglued to the keys.

The Extra has been busy and is clearly a dab hand at stagecraft. The whole set-up works as avant-garde installation art. A Child (Lee Jun Goo) is also present, tied up, gagged and covered over with a sheet to begin with. The Extra has an ultimatum: to secure the release of himself and his Wife, the Director must kill the child, who is a stranger to him. At set intervals, the Extra will cut off one of the Wife’s fingers and finally kill her when she runs out of fingers.

It feels like a claustrophobic one-act stage play, or an audition piece. Admittedly, the premise is inventive, and the actors all perform brilliantly despite a shoddy script that excuses its lack of logic because the scenario is born of insanity. For me, it’s a missed opportunity that the long elasticated cord restraining the Director is not connected to the piano wires that bind his wife. The tension, and literally the suspense, would have been heightened if the Director’s attempts to move across the room to reach her or challenge the Extra had incrementally tightened those wires which are sharp enough to slice cheese, or flesh. Dario Argento wouldn’t have overlooked such an obvious opportunity for a little extra cruelty.

For me, “Cut” is the weakest out of all six segments. Yes, there’s plenty of subtext there about motivations, values, identity and what it takes to drive a good man to do bad things. Its central inquiry question is why bad people get platformed by mass media and are granted much higher profile than the good. I guess those definitions are often subjective, but then again, as Plato said, “good people do not need laws to tell them to act responsibly, while bad people will find a way around the laws…” which reminds me of another of his quotes, perhaps more relevant to the political subtext here, “Those who tell the stories rule society.”

Directed by Takashi Miike, the closing chapter, “Box”, is the superior of all six films presented across both Blu-ray discs. It opens with a dream of a woman being buried alive in what looks like a large, patterned gift box. The woman in the box is Kyoko (Kyōko Hasegawa), and it seems she has been having the same dream over again. In waking life, she’s a novelist who lives in a large semi-derelict building with sparse furnishings and blank, undecorated walls. Throughout, it’s difficult to get a sense of place, of how interiors connect from one room to another or to the outside. It’s as if the environment is compartmentalised into boxes of different sizes—buildings, rooms, lifts… the box created by the frame. There are also metaphorical mental boxes that Kyoko has used to compartmentalise her past, and are we not all boxes of flesh to contain memories?

It seems that Kyoko suffered life-changing trauma in her childhood, the memory of which she has boxed up and buried deep in her subconscious. However, the resemblance that her editor (Atsuro Watabe) bears to a figure from her past threatens to resurface memories of a harrowing tragedy that befell her twin sister, Shoko (Yuu Suzuki), who makes brief spectral appearances. Through her dreams, we learn that Shoko and the young Kyoko (Mai Suzuki) were dancers and contortionists who performed with a circus magician (also Atsuro Watabe) with whom they had a difficult dynamic, as he was their father figure and apparent abuser.

The elusive puzzle that holds the plot together is which twin may have died, if any, and which one lives. The mystery is expertly unpicked with a surfeit of dramatic dreamy imagery that cinematographer Kôichi Kawakami ensures is always breathtakingly beautiful. The final scenes present three equally valid, yet quite different, interpretations, and Takashi Miike stated that this was his intention. He recounts that viewers have asked him which parts were dream and which parts were real, to which he responds that none of it’s real—it’s a film.

And what an astonishingly poetic and deeply poignant film it is. I don’t want to spoil the ending for anyone coming to it fresh, but for me there’s only one explanation that makes sense given all we have witnessed and shared with Kyoko. The final image shows something that is physically impossible and must, therefore, be metaphorical—an externalised expression of her psychological state. This closing chapter for the second, and what turned out to be the final film in the Three sequence, makes the journey more than worthwhile.

HONG KONG • SOUTH KOREA • JAPAN | 2002 | 125 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | CANTONESE • MANDARIN • KOREAN • JAPANESE

directors: Kim Jee-woon (Memories) • Nonzee Nimibutr (Wheel) • Peter Ho-Sun Chan (Home) • Fruit Chan (Dumplings) • Park Chan-wook (Cut) • Takashi Miike (Box).

writers: Jojo Hui & Kim Jee-woon (Memories) • Nitas Singhamat (Wheel) • Matt Chow & Jo Jo Hui Yuet-chun (Home) • Lilian Lee (Dumplings) • Park Chan-wook (Cut) • Bun Saikou & Haruko Fukushima (Box).

starring: Jeong Bo-seok, Kim Hye-soo, Suwinit Panjamawat, Kanyavae Chatiawaipreacha, Pornchai Chuvanon, Leon Lai, Eric Tsang & Eugenia Yuan (Three) • Bai Ling, Tony Leung Ka-fai, Lee Byung-hun, Im Won-hee, Kyōko Hasegawa & Atsuro Watabe (Extremes).