SHINOBI Vol.2 (1964-65)

Three more spectacular tales of ninja action in this continuation of the hugely influential series.

Three more spectacular tales of ninja action in this continuation of the hugely influential series.

Those who enjoyed last year’s excellent triple movie box set, Shinobi (1962–63), will eagerly anticipate this follow-up from Radiance. Making their global Blu-ray debut with these new digital transfers, parts four, five, and six continue the epic nine-film Jidaigeki period saga that can be divided into a trilogy of trilogies. The first three chapters featured the real, but highly mythologised, Ishikawa Goemon (Raizô Ichikawa), a bandit who became associated with the Iga ninja clan and was active in the last decades of the 16th-century as the Sengoku period transitioned into the Edo. Initially envisaged as a duology based on the popular novels by Tomoyoshi Murayama (村山 知義), the first two movies, with Satsuo Yamamoto directing, proved so successful that Ishikawa Goemon was resurrected for a third outing helmed by Kazuo Mori who appears to specialise in concluding trilogies as he’s back for part six, the strongest of this second trilogy.

Vol.2 is what might be called a soft reboot nowadays, and introduces the fictional Kirigakure Saizō (Raizô Ichikawa, again) who appeared in popular literature and kabuki plays during the Meiji Period, thought by some to be inspired by Ishikawa Goemon or a couple of other so-called ninja that history barely mentions. After all, they operate in the shadows, so an effective ninja shouldn’t be well documented.

In addition to pretty much redefining the ninja genre, what made the first films so appealing was the rich back story for Goemon that clearly established his often complex motivations and made sense of some subtle relationships between characters. Here, Saizō is by definition a man of mystery and doesn’t really get a satisfying background except he is also of the Iga ninja clan, one of a handful remaining, and bent on revenge. So, because both are played by the same actor, it’s easy to forget this is a different character. Also, as parts four and five progress, we come to realise he’s an essential component in the back story of his son Saisuke or Kumogakure (Raizô Ichikawa, of course) who will carry part six to the conclusion of the narrative arc while hinting at more to come. Here’s hoping the final trilogy gets a release from Radiance.

Mist Saizo, a legendary folk hero and ninja, working in the service of a warlord, plots to assassinate the Shogun, but finds himself facing the might of the nation’s supreme ruler.

Part 4 opens with a preamble to establish the historical backdrop, specifically the 11th month of the 19th year of Keicho and the ‘winter campaign’ leading to the siege of Osaka Castle. There’s perhaps a bit too much detail, as anyone not well-versed in the history of Japan will be overwhelmed with a list of people and place names. Though this also reminds us of a few significant events, such as the pivotal Battle of Sekigahara, and instrumental characters we may know from the first three films, like the Toyotomi Clan and Ieyasu Tokugawa (Ganjirô Nakamura). I’m sure that, to the audience of its initial theatrical run in Japan, these events would be as familiar as the Gunpowder Plot is to the British, which also played out in the early-1600s. However, just eight minutes in, and there’s another info dump telling us time has passed and we’re already in the first year of Genna… and things don’t get much clearer as the story progresses.

By now, Saizō has already been introduced as a ninja demonstrating his stealth by infiltrating the besieged Shigino Fortress and attempting to rescue Lady Akane (Midori Isomura) while he’s there. We’re given a big clue as to why he’s known as ‘Kirigajure’, subtitled as ‘Mist-Saizō’—he favours the use of dust and fog to conceal his movements and he can, quite literally, disappear in a puff of smoke. He reports back to Yukimura Sanada (Tomisaburô Wakayama), the deposed lord who he hopes will become a figurehead for the rebellion against the nascent Tokugawa shogunate’s power-grab.

We learn that any lords opposing the Tokugawa rule are being stripped of their rank and territories. So, there are thousands of disgruntled and dispossessed ronin wandering the land that Saizō plans to unite in the fight to restore the old feudal order. There are some expositional scenes where the loyalties of various factions are discussed, and strategies are devised accordingly. This aspect of the storytelling is clumsy and too many names and clans are introduced too quickly or mentioned in dialogue without any visual cues to link with who’s who. Although the excess of information lends a sense of historical realism, it’s not essential to follow a story which takes liberties with history anyway.

The narrative is more confused than in the previous instalments, although Hajime Takaiwa remains on script duty. There’s a romantic thread, political intrigue, ninja rivalry, and an altering balance in military dominance due to trade with the Dutch and English gun suppliers. As a character comments, in such times, only the merchants do well. However, these elements aren’t given enough room to breathe, constantly vying for the viewer’s attention without managing to hold it. None come to the fore except the relationship between Lady Akane and Saizō.

So, it’s best to focus on the human-scale stories and let the political machinations and historic events just merge into an evocative backdrop—don’t worry too much about keeping track. For the purposes of this narrative, it’s pretty clear who the good and bad guys are. Already, this is an interesting twist on conventional chanbara movies where samurai are usually the honour-bound good guys and the ninja the unscrupulous villains, willing to sell out anyone for a price. Saizō is not necessarily honour-bound but does jump at any chance to quote the uncompromising ninja code he lives by.

As would be expected from a cast of contracted Daiei talent based at the Kyoto studios, all the performances are solid. Having said that, none are really stand-out. They would’ve been accustomed to similar period roles and at times they seem to be going through the motions, getting the job done professionally and efficiently. The big battle scenes, dynamically staged to convey chaos, must’ve consumed a big chunk of the budget with plenty of extras, horses and explosions but they’re mainly spectacle and noise without significant narrative drive.

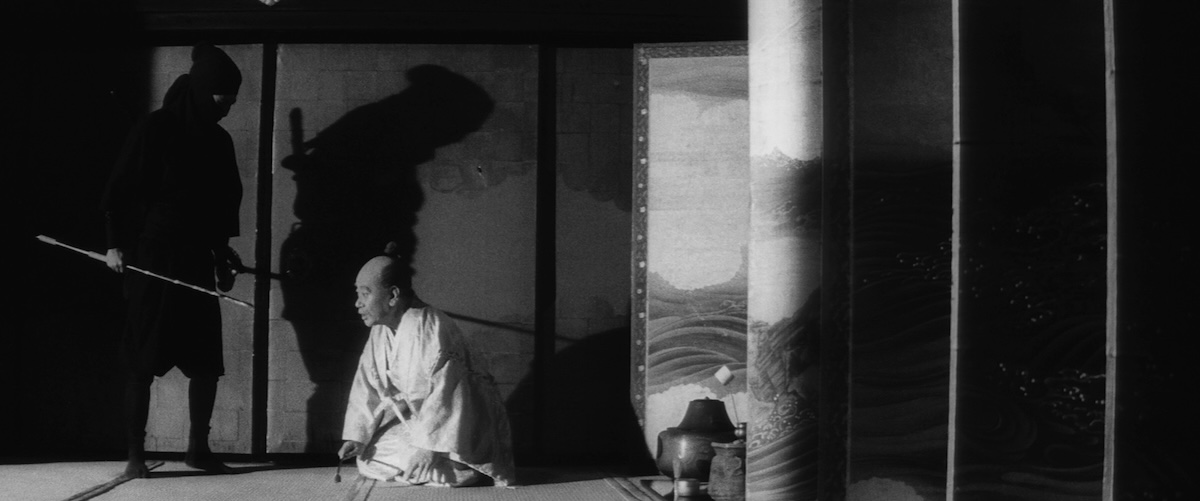

The ninja skirmishes are well-choreographed with acrobatic tumbling and flaming shuriken streaking through the darkness, but the strident music by Akira Ifukube is overbearing and tends to diffuse rather than enhance suspense. For the most part, the choice of framing is interesting and perhaps shows an influence from manga, which was becoming increasingly popular at the time. On occasion, half the screen is in darkness with an illuminated interior asymmetrically framing the action. There’s a detectable, and probably mutual influence, of Akira Kurosawa. Which should come as no surprise…

Director Tokuzô Tanaka got his career off to a good start with a hat-trick of important movies working with two of Japan’s top directors. He was assistant to Akira Kurosawa on Rashomon (1950), then to Kenji Mizoguchi for Ugetsu (1953) followed by Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His last film as assistant director happened to be Kon Ichikawa’s Conflagration (1958) with Raizô Ichikawa in the lead—considered to be the actor’s breakout performance for which he won a handful of prestigious accolades including the Blue Ribbon and the Kinema Junpo Award. With his directorial debut, Ghost-Cat / 化け借御用た / Bake neko goyôda (1958) Tokuzô Tanaka would work with the actor again, and again. Of Tokuzô Tanaka’s first 11 films as director, Raizô Ichikawa would appear in 10, and they would repeatedly collaborate until the actor’s untimely death in 1969, perhaps most notably Sleepy Eyes of Death 1: The Chinese Jade (1963), the first instalment of what would be another long-running franchise. Also set in the Edo period, Raizô Ichikawa starred as legendary ronin Nemuri Kyoshiro in the first dozen movies. At the time, he was the top star contracted to Daiei studios, and very busy filming half a dozen Sleepy Eyes of Death instalments alongside the three Shinobi films presented in this set.

JAPAN | 1964 | 87 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

Mist continues his mission to avenge his master, even after Ieyasu has abdicated from the throne.

It’s well worth persevering through Part 4 to get to this superior segment from this time helmed by director, Kazuo Ikehiro. This isn’t a sequel but a direct continuation, shot back-to-back and picking up exactly where the last film left off. Raizô Ichikawa reprises the lead role of Mist-Saizō and Tomisaburô Wakayama is back as Lord Yukimura Sanada. Both have settled into their roles by now—Raizô Ichikawa using his face and whole physique to convey plenty of unspoken thoughts and shrouded emotions while Tomisaburô Wakayama brings his screen-commanding yet subtle bearing once more. He’s one of those rare actors that draws the eye even when he’s motionless in the background of a scene. He’s perhaps best known as Ogami in the Lone Wolf and Cub movie series and its pop-art mash-up Shogun Assassin (1980). One thing that might be a little disconcerting, if watching these movies in rapid succession, is the use of the Daiei ensemble cast. We have the same faces cropping up as different characters and sometimes the same characters played by different actors. But because Siege was so muddled anyway, this doesn’t really become too much of an issue here.

Many viewers will be coming fresh to this set of movies, so I’ll avoid giving too much away while discussing parts five and six, both of which are stronger than Siege. Straight away it’s apparent that the ninja set-pieces will be more ambitious. Within the first ten minutes or so we have some underwater fighting, at night, amid a thick sea mist that Saizō makes use of. The logistics of choreographing and shooting this must have been problematic but we can certainly follow what’s happening as several ninja in black night camouflage fight in dark water. This is the élan one might expect from Kazuo Ikehiro in collaboration with Chikashi Makiura, the cinematographer who would also lens what is arguably the most beautiful film to come out of Daiei Studios, The Snow Woman / 怪談雪女郎 (1968).

This time around, Hajime Takaiwa’s screenplay handles the political complexities with aplomb and keeps the narrative relatively uncluttered although there’s more going on at the human scale. The influx of foreign influence is driving change as the sword and spear defer to guns and cannons. Saizō longs for a return to the old ways and in this, his goals are partially aligned with his sworn enemy Ieyasu Tokugawa (Eitarô Ozawa) who is about to be declared shōgun—the most powerful political position at the time. This will usher in the Edo Period when a strict feudal hierarchy was established, guns were all but banned, foreigners were expelled and any overseas trade strictly controlled via a single island port in the region of Nagasaki.

Of course, Saizō doesn’t know this will transpire and hopes to coincide an uprising against the Tokugawa clan when Ieyasu finally becomes shōgun. His first mission is to infiltrate a secret organisation of gun-makers who have stolen the plans to manufacture quality rifles with long, rotating barrels that effectively increase the firepower of each soldier threefold. He also uncovers illegal gunrunning to the Ming who are evidently planning some sort of clandestine rebellion of their own in mainland China. Now, this kind of historical referencing adds to the interest and intrigue rather than increasing confusion although there are a few red herrings thrown in to maintain a sense of realism.

Act two plays through several tropes associated with the western genre which at the time was looking to Japan’s chanbara movies for inspiration. This symbiosis manifested most obviously in Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars (1964) released the same year and clearly a loose remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961). Here we have the stoic lone hero, gunrunners, the Ming gang standing in for Mexican bandits, mining towns, bars and brothels.

As the romantic thread from Siege took a tragic trajectory, Saizō becomes involved with sisters, Akemi (Yukiko Fuji) and Manazuru (Masako Akeboshi) who initially jostle for his attention. However, as we have come to expect in the Shinobi saga, things aren’t as simple as they may seem. We learn that their father was one of Saizō’s past victims, or at least that’s how they understand it, and they’ve been raised and indoctrinated by a rival ninja clan. Perhaps a rather contrived plot device, but through the dynamic of this potentially lethal love triangle the conflicts between honour, duty, and love are explored as well as the life choices of trying to relive the immutable past or preparing for an unknown but potentially brighter future… In this way, these few individuals become metaphors for the choices facing a nation in flux, teetering between inevitable war and potential peace. It’s odd then that our protagonist is effectively trying to engineer a war, ostensibly to overthrow an oppressive régime, but is it really because his ninja skills have little value in times of peace…

The fight scenes are all cleverly staged in silence for the most part. The sense of tension is elevated when music cues are absent and all we hear is the rhythm of footfalls, rustle of cloth, the woosh of flaming shuriken, the ring of blade, the thud of flesh, and an occasional death gasp. Much of the action takes place at night with deepest chiaroscuro and there’s some clever deception and misdirection on Saizō’s part that gets him out of a few near-death scrapes. This is more like the Shinobi we came to know through Vol.1.

JAPAN | 1964 | 91 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

Mist’s son takes over his father’s name and mission, and is recruited by a rebellious warlord to assist a plot to overthrow the government, but the Shogun hires a rival ninja clan to thwart the uprising.

Raizō Ichikawa is back again, this time in a dual role. He appears briefly as Kirigakure Saizō to pass his ninja dagger to his young son Kumogakure and to reveal that the boy’s little sister, Yuri, was adopted and is the daughter of Lord Yukimura Sanada. The narrative then jumps forward 20 years to what we’re told is the third year of Keian, or 1650, and we’re struck by the uncanny family resemblance of the grown-up Kumogakure Saizō (Raizô Ichikawa). We now realise that Siege and Return of Mist Saizō were there to provide backstory.

In the first trilogy, the finale was the weakest of the three. This time around, the third film is the strongest. Both are directed by Kazuo Mori, a veteran who was working for Shinkō Kinema before they were part of the studio merger that formed Daiei in 1942. The assuredness of this chapter is perhaps also down to the fresh writing team of Kei Hattori, making their debut, and the more experienced Kin’ya Naoi, who already had some 20 scripts to his name. Their story centres on Saizō taking up his father’s vendetta against the Tokugawa Shōgunate because, as he puts it, “This peaceful world is evidence of our stolen freedom.” An odd stance to take, but it was true that peace was maintained during the Edo period by an elaborate system of inviting key family members of each major clan to stay as guests at the shōgun’s palace. These semi-permanent ‘guests’ were effectively hostages to keep the other samurai lords obediently in line. Viewers who followed the recent remake of James Clavell’s novel, Shōgun (2024), will already know this.

The Last Iga Spy is the most intricately plotted of the three Shinobi films in this box set and the most philosophical. It also has some cleverly choreographed set-pieces that play out mostly in silence with selective foley instead of music to build tension. There’s a ninja duel across rain-swept rooftops, wonderfully shot by cinematographer Hiroshi Imai, and another beautifully staged, complex battle in a closed theatre at night between one ninja and many opponents, accompanied by lantern-bearing attendants. There’s also a rival ninja clan on the rise with a cunning lady spy (Kaoru Yachigusa) fond of deadly poison darts. Yes, the Shinobi franchise is a known influence on the James Bond films—remember the ninja in You Only Live Twice (1967).

Ultimately, Saizō hopes to orchestrate an attack upon Edo Castle and dethrone the shōgun. Like his father, he intends to utilise the unemployed rōnin, who now number in the hundreds of thousands and are struggling to earn a living or turning to crime. To begin with, Saizō keeps to the shadows and, with the help of military scholar and dojo master Masayuki Yui (Mizuho Suzuki), manipulates allegiances by stealing sensitive information and disseminating it to those it may provoke into action. As the plot develops, though, we begin to realise that the unscrupulous elite in positions of political power are even sneakier than old-school ninja. As Saizō’s plans begin to unravel, he must choose what’s more important to him—overthrowing the shōgun or protecting his family. Will he choose the political or the personal?

JAPAN | 1965 | 89 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

directors: Tokuzô Tanaka (Siege) • Kazuo Ikehiro (Return) • Kazuo Mori (Last)

writers: Hajime Takaiwa (Siege & Return) • Kei Hattori & Kin’ya Naoi (Last).

starring: Raizô Ichikawa, Ryuzo Shimada, Koichi Mizuhara, Saburô Date, Tomisaburo Wakayama & Katsuhiko Kobayashi.