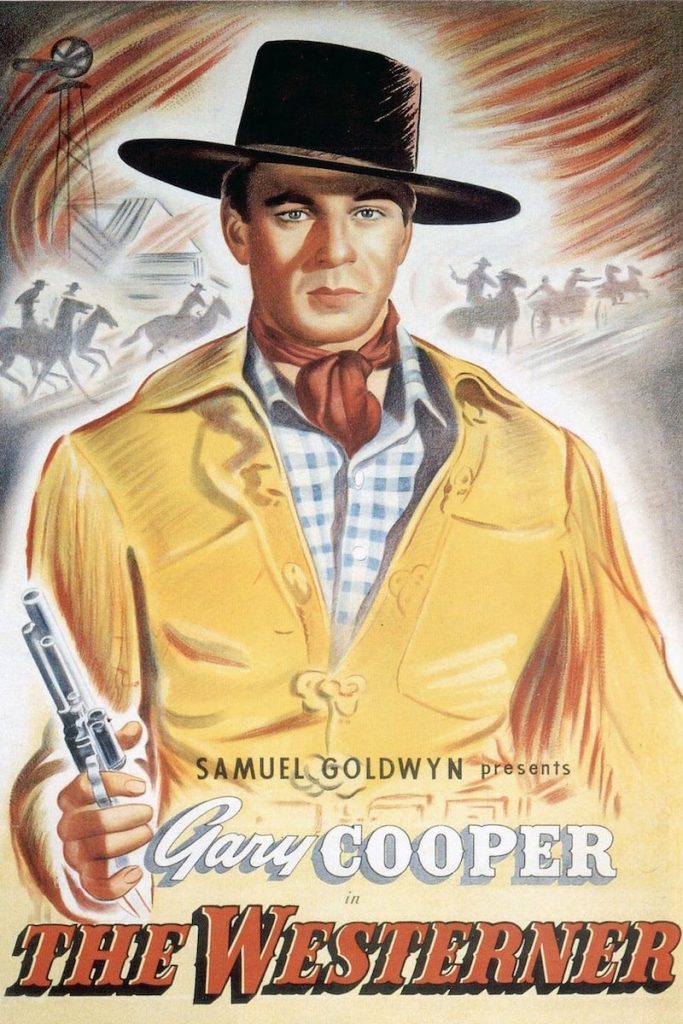

THE WESTERNER (1940)

Judge Roy Bean, a self-appointed hanging judge, befriends saddle tramp Cole Harden, who opposes Bean's policy against homesteaders.

Judge Roy Bean, a self-appointed hanging judge, befriends saddle tramp Cole Harden, who opposes Bean's policy against homesteaders.

William Wyler’s The Westerner begins and ends with wagon trains and maps of Texas, setting it firmly in the corner of the Western genre concerned with the settlement of a specific geography and, by extension, the creation of the modern United States itself.

Its purported plot is a common one: the conflict between ranchers who want the land left open for their cattle and farmers who want to use it for crops. But The Westerner achieves its most enduring charm as a kind of reluctant-buddy movie. And its proposed solution to this conflict is, of course, democracy and the rule of law. “Why don’t you be a real judge for all of the people?” Cole Harden (Gary Cooper) asks Judge Roy Bean (Walter Brennan).

The film properly starts with an action sequence establishing the land conflict, but its lead duo appears first in a different context some minutes later. It’s 1882 and Harden has been brought cuffed into the saloon in Vinegaroon, Texas, where Bean holds his dubiously legal trials. Harden (the titular westerner) is accused of being a horse thief, but he’s obviously innocent as he’s played by Gary Cooper.

In the classic model of the Hollywood Golden Age’s western hero, Harden hails from “no place in particular”, is heading “no place special”, and doesn’t want to settle down. But he’ll inevitably soon be defending those who have settled, and just as inevitably get the girl and set up house himself.

For now, though, he faces hanging for the horse theft. Bean’s absurdly unfair court seems never to find anyone innocent, or impose any sentence less severe than the gallows. (This isn’t historically accurate but clearly makes for a better story than the truth—as the real Bean generally preferred fines to executions. However, he genuinely did run an idiosyncratic justice system in Vinegaroon only some 60 years before the film was made, with minimal knowledge of the law and no regard for correct procedure.)

A young local woman, Jane-Ellen (Doris Davenport), attempts to intercede on Harden’s behalf, but what really saves him is his discovery of the judge’s obsession with young British actress Lillie Langtry, a glamorous figure who had recently shot to stardom on the London stage and began an American tour in 1882. She appears at the end of The Westerner, played by Lilian Bond, but her name and her image figure prominently throughout. Indeed, the judge will soon rename Vinegaroon as Langtry in her honour. (This also actually happened.)

In any case, Harden pretends to know Langtry and thus obtains a stay of execution from Bean. Much of the film’s humour comes from Harden’s desperate skin-saving claim to possess a lock of the actress’s hair. But this is dramatically significant too: the moment where he persuades Jane-Ellen to part with a lock of her hair, claiming it’s for him to remember her by (although he really needs it to carry on fooling Bean), is the moment where her affections tip away from a neighbouring boy and toward Harden.

Bean and Harden become friends, of a kind, but are never completely trusting. At one point, when Harden leaves Bean to get a warrant for his arrest, Bean’s hand goes to his gun as if to shoot Harden in the back… and then stops, despite Harden having almost dared him to do it. It’s a moment typical of The Westerner, which like many of the best 1940s Hollywood movies s unshowy and sophisticated in its storytelling. A movement here revealing both the knife-edge nature of their relationship and the essential goodness of the superficially ruthless Bean.

Barely connected to this is another parallel storyline: the familiar one of the cattle ranchers versus the farmers. Bean is very much on the ranchers’ side, but Jane-Ellen’s family are farmers, and it’s naturally down to Harden to attempt to reach an arrangement that’s fair to both sides.

As Western stories go it’s a pretty standard-issue one, but The Westerner is rescued from potential mediocrity by superb filmmaking and, in at least one case, acting.

The visual flair of Wyler (who had been directing since the silent era but had only become a big name in recent years, for example with 1940’s Rebecca) and his cinematographer Gregg Toland (a regular Wyler collaborator but most famous for 1941’s Citizen Kane), is clear from the excellent opening where cowboys come across a fence set up by the “cornhuskers” to protect their crops from the cattle. (For once we get to see cowboys with actual cows!) Shooting erupts and triggers a sequence full of movement and contrasts; between the mounted cowboys and the farmers on foot, the planted field and the open range.

Even more impressive is a later sequence where community prayers in front of the cornfield form a kind of miniature photo essay on the people and the land. This is soon contrasted with the tumult and shock of burning crops, in an exciting action sequence (aided by Dmitri Tiomkin’s score) full of telling details like the farmers setting pigs free to save themselves. That, in turn, is supplemented by a poignant scene that refers back to both the prayers and the burning, where Davenport prays over her father’s gravestone (with its handwritten inscription) in the ruined field, reading from a half-charred family Bible.

Throughout, Toland makes the most of the landscapes in the film’s Arizona locations (although other parts of it were obviously shot on a backlot) but even the interiors are unusually physical too: we see a horse lumbering through Bean’s bar, spilt liquor fiercely bubbling on the bartop, a man not just clambering over a table but upsetting glasses as he goes. In a theatre scene at the end, when fighting breaks out, the musicians crouch and flee just as patrons normally would in a Western bar brawl. This scene concludes with one of the film’s most effective shots as the curtain descends on the stage, but we see only its shadow falling over the empty auditorium.

As compelling as the visual presentation of The Westerner is Brennan’s performance as Bean. Twinkling and threatening in equal measure, he keeps the self-serving and idealistic halves of Bean’s character in a perfect yet constantly shifting balance. This is well illustrated during his first encounter with Harden, where Bean is both utterly corrupt and utterly in control of the situation until Harden mentions Lily Langtry—at which point he softens into complete sentimentality. Bean, of course, would much later get a film all to himself (1972’s The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean, written by John Milius and directed by John Huston).

Cooper, though a much bigger star than Brennan (in 1937 he overtook Mae West as Hollywood’s highest-paid performer) and lately moving far beyond the Westerns where he first made his name, pales a little beside Brennan. But he still makes the most of his part, giving Harden some ambiguity at least until it’s obvious that he’s going to be the good guy. (While Bean’s venality is plain for all to see, we’d also wonder for quite some time just how honest Harden is… if he weren’t portrayed by Gary Cooper.)

Much of the first half-hour of The Westerner is essentially a Brennan-Cooper two-hander, and they continue to dominate the movie. They would also go on to even greater cinematic success together in Howard Hawks’ Sergeant York (1941).

Few of the other actors make an appreciable impact, partly because the screenplay allows them little scope to do so, though Davenport at least holds her own. Unlike Cooper and Brennan, she was an unknown before The Westerner, where producer Sam Goldwyn gave her the female lead after being impressed by her screen test for the Vivien Leigh role in Gone With the Wind (1939). Her chance at stardom led nowhere, though, and she made only one other film.

In much smaller roles there’s an amusing cameo by an uncredited Lew Kelly as a theatre usher… while Dana Andrews, soon to become a major name (not least in Wyler’s 1946 film The Best Years of Our Lives), appears as one of the farmers.

Several perhaps unexpected big names also worked off-camera without credit. Lillian Hellman was already a significant playwright by the time it was released, with The Children’s Hour (1934) and The Little Foxes (1939) to her name, but she was a salaried screenwriter for Goldwyn as well, and contributed to The Westerner’s script. The great Lewis Milestone, feted for All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), directed some additional scenes when principal photography was finished and Wyler and Toland were no longer available. And Alfred Newman, already an Academy Award-winning composer, added to Tiomkin’s fine score.

While not on a par with Toland’s contribution, Tiomkin’s work for The Westerner also adds much to the film and is memorable for some great chase music in full-on cowboy idiom—rendered slightly ironic by the fact that it’s not the white hats chasing the black hats, but Bean chasing Harden to remind him about Lily Langtry’s hair. As so often in Westerns of the period, there are also the usual slightly implausible bands popping up to add a bit of diegetic musical spice.

The Westerner received a mixed reception from critics, though Brennan’s performance was singled out as a highlight. He “turns in a socko job that does much to hold together a not too impressive script”, Variety opined, while also praising “eye-filling scenic backgrounds that are accentuated by expert photography”. The mighty Bosley Crowther, meanwhile, quipped in The New York Times (for which this must have been one of his first reviews) that “Gary Cooper is an exceedingly modest fellow—too modest for his own good, perhaps. For in Samuel Goldwyn’s The Westerner… he casually permits the most important role in the picture to be taken away from him and bestowed upon capable Walter Brennan.”

Predictably enough, then, it was Brennan who took home The Westerner’s only Oscar, as ‘Best Supporting Actor’ (his third), although it was also nominated for best art direction and best story.

The Westerner isn’t a perfect film, partly perhaps because it’s almost too good-natured. It doesn’t really have a villain! The New York Times’s Crowther also observed, rightly, that the movie’s divided attention isn’t satisfactory. It never seems sure whether it wants to be about the land conflict and the related (rather uninteresting) Harden/Jane-Ellen romance, or about the Harden/Bean relationship, which really are quite different tales.

But even if it falls short of true classic status, Brennan’s performance and Toland’s photography alone are good enough reasons for it to be remembered, as a sturdy, beautifully-crafted example of a genre approaching its own Golden Age.

USA | 1940 | 100 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: William Wyler.

writers: Niven Busch, Jo Swerling, W.R Burnett, Lillian Hellman & Oliver La Farge (story by Stuart N. Lake).

starring: Gary Cooper, Walter Brennan, Fred Stone & Doris Davenport.