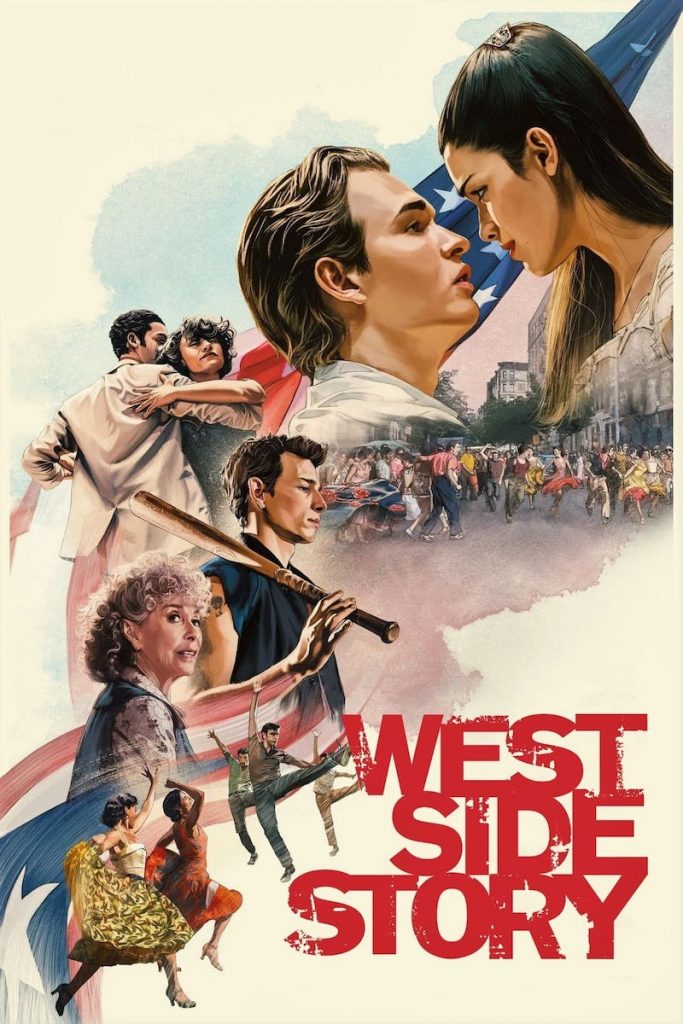

WEST SIDE STORY (2021)

Steven Spielberg remakes one of the most famous musicals ever, a tale of love and murder in the slums of 1950s New York

Steven Spielberg remakes one of the most famous musicals ever, a tale of love and murder in the slums of 1950s New York

Steven Spielberg doesn’t make bad movies. But he doesn’t always make great ones, and adapting West Side Story was inevitably going to be a risk. Not only is the original a revered masterpiece of musical theatre, sitting right at the heart of the canon, but the 1961 film adaptation by Robert Wise continues to be acclaimed, while countless productions on professional, amateur, and school stages leave everyone sure they know what West Side Story “is”. Tamper with it at your peril?

However, at the same time there’s also been disquiet over stereotyping of Puerto Ricans in the stage version (which debuted on Broadway in 1957) and the 1961 movie, exacerbated by the latter’s casting of many white performers—notably Natalie Wood, who played Maria—in Latinx roles.

Of course, this possibly says as much about our own time as about the intentions of Jerome Robbins (who conceived the show), Arthur Laurents (who wrote the book), Stephen Sondheim (who wrote the lyrics, and only died recently), and Leonard Bernstein (who composed the music). As theatre critic Jesse Green wisely opined in The New York Times recently, West Side Story—a loose adaptation of Romeo and Juliet, with white and Hispanic gangs standing in for Montagues and Capulets respectively, and the characters of Tony and Maria reincarnating Romeo and Juliet—was “an idea looking for an ethnicity… in landing on Puerto Ricans vs. whites (instead of Jews vs. Catholics as originally imagined), it was taking advantage of a news hook of the time without any deep engagement in Puerto Rican-ness”.

In other words, it was never intended to be about the situation of Puerto Rican immigrants in New York, or for that matter poor whites either—they’re merely convenient settings for a love story which requires two conflicting groups—and though it may certainly have reinforced some pre-existing prejudices, few people in 1957 or since can have taken it seriously as a documentary. If West Side Story had depicted the lives of any of its characters realistically, it wouldn’t have been West Side Story.

To their credit, for this new version, Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner (who previously worked on the director’s Munich and Lincoln) have both addressed the concerns over casual racism in West Side Story and also refused to let their corrective measures dominate.

Most obviously, the Hispanic characters are now played by actors of similar ethnic backgrounds, something which greatly benefits the movie in every respect. The decision not to subtitle the fairly extensive Spanish-language dialogue has been questioned, but it’s difficult to see any solution which would work better (subtitling Spanish only implicitly makes it an “un-American” language; subtitling Spanish and English would draw painful attention to itself for more than two and a half hours). In any case, it will be easy enough for non-Spanish-speakers to guess what’s going on.

Perhaps more unexpectedly, but also successfully, Spielberg and Kushner have reframed West Side Story as a film about change and a now-lost era. Key to this production is the notion that the neighbourhood where two gangs, the Jets (Montagues) and Sharks (Capulets), play out their essentially pointless but often deadly serious power struggles, will soon be demolished. All the lead characters’ way of life is doomed anyway, as is star-crossed Tony and Maria’s love. Police lieutenant Schrank (Corey Stoll) calls the Jets the “last of the can’t-make-it Caucasians”, and their leader Riff (Mike Faist) confesses that the gang is all that’s left for him in life.

Moreover, the streets of tenements and cheap stores and gymnasia and bars are being knocked down to make way for the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts: a place that will be “not for us, for the gringos”, as one of the Latinx women observes. And, of course, particularly for the likes of educated, well-off gringo intellectuals like Bernstein and Sondheim. This half-wry nod to class guilt as well as white guilt exemplifies the careful judgement that has gone into this West Side Story: the film doesn’t pretend that the world and its attitudes haven’t changed in the 60 years since the first movie, but nor do Spielberg and Kushner allow the whole thing to turn into an apologia. They make this acknowledgement, then move on with the story.

And it’s done so well that it’s impossible not to be swept away. Indeed, I’m tempted to say it’s an even more engaging and entertaining movie than 1961 version, if not quite so fresh in its cinematic ideas. It does retain much of the general feel of the first version but continually adds its own twists. For example, the opening seconds again set a soundtrack of whistling against a completely black screen, but where Wise then served up a series of aerial shots of New York City in all its romance and grandeur, Spielberg’s camera hovers just a few feet above the ground, passing over debris, eventually revealing a demolition site.

Some famous sequences—such as Tony’s solo “Maria” in the night-time streets and the Tony-Maria duet “Tonight” (almost literally a balcony scene except that the balcony is a rickety fire escape)—are similar enough to the original film that we’re obviously intended to recall it with affection. Others are very different. “America” is relocated from a rooftop to the streets (and this, the wittiest number by far, works even better there). “I Feel Pretty” has been given a much more interesting setting than in ’61, now taking place in Gimbels department store, where the Latinx women work as cleaners surrounded by mannequins of affluent Anglos.

There are no major changes to the story itself, but there are big shifts in some characters. Most dramatically, the Jewish drugstore owner Doc—a confidant and mentor for Tony—has become a woman called Valentina, played by Rita Moreno (who played Anita in the original film). She’s Doc’s widow, and as such has her own perspective on mixed-race relationships. Moreno is terrific, and giving her the song “Somewhere”(originally sung by Tony and Maria) is a stroke of real genius, as experience lends deeper meaning to its plea that we “find a way of forgiving.”

Less drastic but still striking, reworked characters include Anybodys (Iris Menas), a tomboy in the original, who’s now transgender; and Chino, the young Puerto Rican man whom the community hopes will marry Maria. 60 years ago he was something of a non-entity, but Spielberg and Kushner have turned him into a likeable nerd (studying adding-machine repair) whose transition into a vengeful killer is thus all the more impactful. Josh Andrés Rivera portrays him thoughtfully, not playing the nerdishness for cheap laughs.

In the 1961 film, Richard Beymer as Tony was a bit of a problem, being too matinee-idol in his appearance and given to excessive emoting (as during “Something’s Coming”). Here, Ansel Elgort (Baby Driver) fares far better, though he’s still a little too preppy. His drift away from the Jets is more heavily emphasised, though, and justified by a frequently-referenced backstory, so the contrast between Tony and his contemporaries is not quite so painful.

No performance here is a let-down, but the real stand-outs are Rachel Zegler as Maria and—unexpectedly, given he’s a secondary character albeit an important one—a magnificent Faist as Riff. The sense of angry frustration in Riff is palpable, and you can feel that in a different life this young man could be much more than the leader of a street gang.

Zegler’s Maria, meanwhile, is ambitious, strong, and opinionated. Her interactions with her brother Bernardo (David Alvarez), the leader of the Sharks, and his girlfriend Anita (Ariana DeBose, similar in many respect to Maria but more mature) are among the movie’s best scenes, and her performance of “I Have a Love” is perhaps the musical and emotional highlight of the film.

The other big numbers mostly stand up well alongside the 1961 versions. “Maria” is perhaps a little less magical, but “Tonight” is far more thrilling, with a supremely romantic conclusion. Little touches, like Tony’s flat pronunciation of “te adoro, Maria” (he doesn’t speak Spanish), add much. “Gee, Officer Krupke” is delicious and wonderfully-timed, with the unfortunate officer himself showing up aghast at the very end of it; in that song the movement of the performers themselves is antic, but in the “Tonight” quintet that leads up to the rumble (gang fight) it’s the editing that provides choreography.

There’s lots of new dialogue, most of it successful, and even a few lyric changes. For example, “pretty and witty and gay” in “I Feel Pretty” becomes “pretty and witty and bright”, while slightly less explicably “organised crime” in “America” becomes “serious crime”. A few of Sondheim’s duds remain (such as the awkward “suns and moons all over the place” in “Tonight”); Kushner adds a few others (is it really plausible that Riff, not at all stupid but surely not very educated, would refer to a “shot heard around the world”?)

Visually, as elsewhere, Spielberg preserves the spirit of the original without replicating it in detail. Most notably, he and cinematographer Janusz Kamiński (Schindler’s List) move away from the strongly geometrical compositions of 1961 (where parts of buildings, chainlink fence and so on constantly complemented the choreography) in favour of more naturalistic backdrops. The shapes are there, for example in the rumble, but they’re not really emphasised until the end credits.

The boys are dirtier, the streets are more populated (with black people more visible), and there’s an abundance of stuff generally, as well as incidental business with it (a bar sign, a vegetable truck…) The gym dance, some of it shot in near-abstract style in 1961, is here presented more plainly.

But in his directorial approach Spielberg does glance back to the first film, incorporating just enough of its visual atmosphere to keep it in audience’s minds. For example, where Maria’s first scene in 1961 was heavily colour-coded with an emphasis on purples, here it’s the gym dance that receives that treatment (the Jets all in shades of blue, the Sharks in much more motley colours).

None of this, of course, would be of more than academic interest if the film weren’t so damn good. But, while it is maybe less adventurous and less sharp-edged than Wise’s version, everything in Spielberg’s West Side Story works just as well in its own right, and for those who think the classics can’t be satisfactorily remade, it is just as much as A Star is Born (2018) a reminder that sometimes they can be.

Leonard Bernstein reportedly felt overshadowed in later years by West Side Story, and probably would’ve preferred to be remembered for work like Candide or the Chichester Psalms. That is, however, his own fault for doing West Side Story so near-perfectly. Sondheim actually did go on to produce better things than his West Side Story lyrics once he started composing as well as writing—perhaps the best of all, in their very different ways, being Sunday in the Park With George and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street.

But for all their indisputable merits, none of these has achieved anything like the legendary status of West Side Story. It’s famous, beloved, and admired for good reason (popularity doesn’t necessarily equate to poor quality)—and now Spielberg’s new version, which loses none of the original’s most important strengths while adding its own additional layers of meaning, may help to consolidate the legend further and for new generations. This time, he has made a movie that is not just good, but at least verges on greatness; a pity it’s come a few days after for our Spielberg favourites feature, because it surely belongs there.

USA | 2021 | 156 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • SPANISH

director: Steven Spielberg.

writers: Tony Kushner (2021 screenplay), Stephen Sondheim (lyrics) & Arthur Laurents (original stage play).

starring: Ansel Elgort, Rachel Zegler, Ariana DeBose, David Alvarez, Rita Moreno, Brian d’Arcy James, Corey Stoll, Mike Faist & Josh Andrés Rivera.