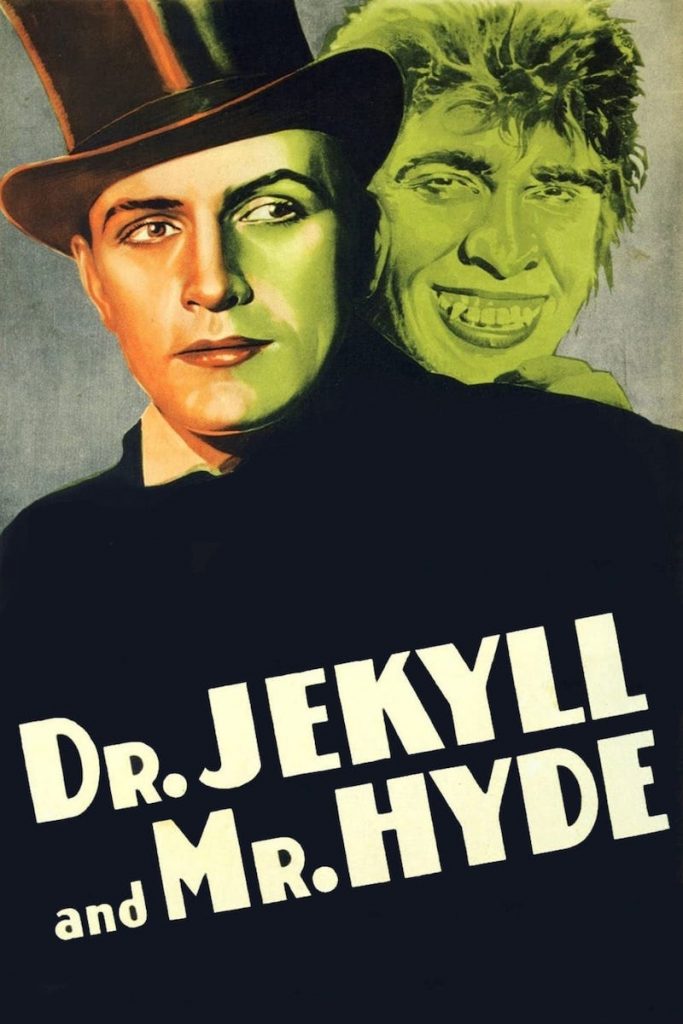

DR. JEKYLL AND MR. HYDE (1931)

Dr. Jekyll faces horrible consequences when he lets his dark side run wild with a potion that transforms him into the animalistic Mr. Hyde.

Dr. Jekyll faces horrible consequences when he lets his dark side run wild with a potion that transforms him into the animalistic Mr. Hyde.

90 years ago was a good time to be terrified at the local picture palace. Tod Browning’s Dracula, with Bela Lugosi in the title role, appeared in February; James Whale’s Frankenstein with Boris Karloff as the monster followed in November; and then, just as 1932 was about to dawn, Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde completed the unholy trinity.

All three were significant commercial successes and, although some at the time thought that scary movies would be a short-lived fad, they inaugurated horror as a Hollywood genre. Its emphasis did shift several times over the coming decades, of course—toward science in the 1950s, for example, fed by the real horrors of recent history, and then to the occult in the 1970s—but the direct influence of the Dracula/Frankenstein/Jekyll and Hyde trio remained considerable, not only in the frequent reappearances of celebrated characters but in individuals’ careers too. Karloff and Lugosi would both star in horror movies almost every year of the 1930s and 1940s.

Fredric March, who played the title roles in Jekyll and Hyde, didn’t. Indeed, horror is almost completely absent from his filmography. A revered actor in his time if one whose fame has rather receded today, he tended to prefer prestige projects like A Star is Born (1937) and Death of a Salesman (1951), and for all that horror could be profitable, it was rarely prestige.

This absence of a name associated with the genre may explain why Jekyll and Hyde has never achieved quite the pop-culture celebrity of the same year’s Frankenstein and Dracula. But it’s easily their equal and widely regarded as the best adaptation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 novella, which had been filmed as early as 1908 and at least 10 times before the Mamoulian version. This is probably more than either Dracula or Frankenstein and is little surprise; Jekyll and Hyde, with its relatively small cast of characters, its tight plot, and limited settings, lends itself easily to adaptation. Indeed, it had been presented on the stage only a year after publication of the novella, although the production was soon closed when it was suggested it might have inspired Jack the Ripper.

Before Mamoulian and screenwriters Samuel Hoffenstein and Percy Heath took up Stevenson’s story, the best-known cinematic adaptation had been in the 1920 version with John Barrymore in the title role. Like March, Barrymore was a high-class actor not given to playing monsters, and his Hyde was acclaimed as appropriately shocking. But March and the 1931 production team took Hyde to a freshly disturbing level, being more creature than man. Mamoulian described his conception of Hyde as “Neanderthal”, and as the film progresses he becomes both more decrepit and more animalistic, climbing like a monkey at the end.

The transformation sequences are beautifully handled–though the camera does move away discreetly at certain moments, much of the actual change from Jekyll to Hyde is in plain view, via trickery kept secret at the time. It was decades later that cinematographer Karl Struss revealed it was achieved through coloured makeup and filters. A blurry montage of memories and unearthly sounds (“Mamoulian’s stew”, including gongs and hearbeats) heightens the effect of the first change.

March himself also does an enormous amount to define the character, with his terrifically physical performance, and of course it’s Mr Hyde rather than Dr Jekyll whom we remember most. The first time Hyde emerges from the laboratory says so much about him: he pauses briefly as if new to the world (you can almost imagine him sniffing the air), then hastens on as if he can’t get enough of it to satiate his appetites. Throughout, his movements are hurried. He twitches and rubs his fingers in nervous excitement. He laughs, and laughs, and laughs; his grin being the most horrific thing about him. He seems smaller than Jekyll, an impression created partly by ill-fitting clothes.

But he’s not just animal-like, because he possesses many human failings too. He puffs himself up with pride. He’s resentful, suspicious, and quick to anger. He’s violent far beyond necessity too. After a waiter cheeks him, Hyde—completely free of civilising inhibitions—not only trips the man up but proceeds to beat him with his cane. Later, a murder scene is startlingly vivid for the period, with Hyde’s hands on his victim’s throat seen in detail.

And he’s psychologically as well as physically cruel. The film’s most unsettling scenes, where Hyde’s visiting the young woman Ivy (Miriam Hopkins) whom he’s taken on as a mistress, are essentially portrayals of domestic violence, and they highlight the role of mental torture as well as physical violence. Hyde tells her he’s going away, to her obvious relief, then torments her by adding “you don’t know when I’ll be back.”

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a broad-stroke adaptation of the Stevenson story, differing in many details of plot and people. For example, Jekyll here is much younger than Stevenson’s middle-aged character—March was in his early-thirties—and the two main female roles aren’t found in Stevenson’s male-dominated tale). But the central concept is the same. Jekyll, a scientist/doctor in Victorian London, develops a serum which not only transforms him physically but allows what contemporaries would have called his “baser instincts” to take control. Aghast at his own behaviour in his changed state as Mr Hyde, Dr Jekyll stops taking the serum, but then finds himself starting to transform anyway without it.

As his friend Lanyon (Holmes Herbert) says in Mamoulian’s film, “it has conquered you”, and although the line “man is not truly one, but truly two” is used in both Stevenson’s original and Mamoulian’s film, it’s clear that one half of man can gain ascendancy over the other. Jekyll’s intention might have been to remove the bad so that the good can thrive (an idea which could have had fresh resonance in 1931, by which time many audiences would have been familiar with ideas of psychoanalysis), but as in so many horror movies, a perhaps well-motivated experiment has terrible results.

Some of the film’s horror is overt. Much is less so. For example, in an early scene there’s something decidedly unnerving about the way that Mary, a young girl who’s a patient of Jekyll’s, walks toward the camera even though there is nothing supernatural or even narratively unpleasant about the story at this point. Extreme close-ups on Jekyll’s and Muriel’s eyes are similarly effective.

The atmosphere is heightened throughout by the German Expressionist feel of the exteriors created by art director Hans Dreier, and by frequent references to duality, as when Jekyll says to his fiancée Muriel (Rose Hobart) not about Hyde, but about his love for her “it frightens me… you’ve opened a gate for me into another world.” This duality even extends to the film’s structure. For example, the scenes where Hyde promises to leave Ivy and where Jekyll breaks off his engagement to Muriel parallel one another. Hyde tauntingly tells Ivy he might only get as far as the door before looking back at her tears; Jekyll does exactly that with Muriel. Hyde is visibly in a hurry all the time; Jekyll is criticised by Muriel’s father for being “too flighty, too impatient”. One scholar (George E. Turner) has counted the number of scenes featuring either Jekyll or Hyde, and they are almost exactly equal (110 Jekylls and 108 Hydes).

Adding to the discomfiture, at several points Mamoulian puts the audience in a voyeuristic position just as Jekyll himself is a kind of voyeur of Hyde’s depredations, and indeed the movie’s opening has justly achieved fame in this respect. We’re given Jekyll’s point of view in an elliptical, eye-shaped frame; we first see him in a mirror (just as he’ll first see Hyde in a mirror) putting on his smart evening clothes—preparing himself to be seen the way that polite society expects him to be seen. A little later, we implicitly share Jekyll’s prurient point of view when Ivy starts to undress in front of him, too.

Though March in his two forms necessarily dominates the film, and won the ‘Best Actor’ Academy Award for it, other performers contribute much as well. Neither Hobart’s Muriel nor her military-officer father, played by Halliwell Hobbes, are the cardboard cutouts they would be in many movies, and Edgar Norton is especially memorable as Poole, Jekyll’s butler. But the one who shines most of all, and can even match Mr Hyde in their scenes together, is Hopkins as Ivy; a versatile actress who was nominated for an Oscar a few years later, she came to prominence as a result of her role in Jekyll and Hyde, and understandably so. Her fear is all too real, both in her apartment with Hyde and in a later scene where she visits Jekyll and (not knowing his secret) pleads with him to help her.

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde benefited greatly from the still-patchy enforcement in 1931 of the Hays Code, a form of studio self-regulation which later in the 1930s would have made much of it unacceptable. For example, Ivy is obviously a prostitute, and an exchange between Jekyll and Lanyon outside her home is as clear a reference to casual sex as it could be without using the actual words. Unsurprisingly, several minutes were cut from it for reissue in 1935. The story continued to be revisited by filmmakers over the decades that followed—the next major version was in 1941 with Spencer Tracy in the title role and Ingrid Bergman as Ivy—and it also suffered many of the indignities to which legendary horror characters were routinely subjected in the mid-century, with Abbott and Costello inevitably meeting Jekyll and Hyde in 1953, and Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde appearing in 1971. Not all adaptations were crass, as some consider Jean Renoir’s French TV version Le Testament du Docteur Cordelier (1959) to be the best of all.

Still, it’s difficult to imagine Mamoulian’s film ever being eclipsed. It feels dated in only a few respects—maybe overdoing the use of dissolves and particularly wipes, for example—and excessive in a few others, like the bubbling cauldron in Jekyll’s lab. But it’s worth remembering that some horror clichés, like Jekyll playing a pipe organ, were not clichés at the time. And in any case the great achievement of this Jekyll and Hyde lies simply in being horrifying. Everything that’s most important in it—March’s performance, the production design, the key scenes of Hyde’s viciousness—retains a genuine ability to shock and disquiet that’s exceptional for a film almost a century old. If much vintage horror is now appreciated for its nostalgia (or camp) value, Mamoulian’s Jekyll and Hyde still succeeds in doing exactly what it set out to do in 1931.

USA | 1931 | 98 MINUTES | 1.20:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Rouben Mamoulian.

writers: Samuel Hoffenstein & Percy Heath (based on the novella by Robert Louis Stevenson).

starring: Fredric March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart & Holmes Herbert.