THE VIRGIN SUICIDES (1999)

A group of young men become obsessed with five mysterious sisters who are sheltered by their religious parents.

A group of young men become obsessed with five mysterious sisters who are sheltered by their religious parents.

If there’s a moment in Sofia Coppola’s filmography that’s punctured the mainstream consciousness, it’s doubtlessly the scene that comes towards the end of Lost in Translation (2003), when Bob (Bill Murray) whispers into Charlotte’s (Scarlett Johansson) ear. It’s a message important enough for him to make sure she hears it, and is made even more important by the fact we don’t hear it. It takes on the shape of the unknown, a possible confirmation of love, a piece of wisdom, or nothing at all. If that’s the moment of poetic ephemerality she’s most remembered for, then it’s striking that, in 1999, Coppola had already made a film that seemed to be that moment presented as a feature-length dream.

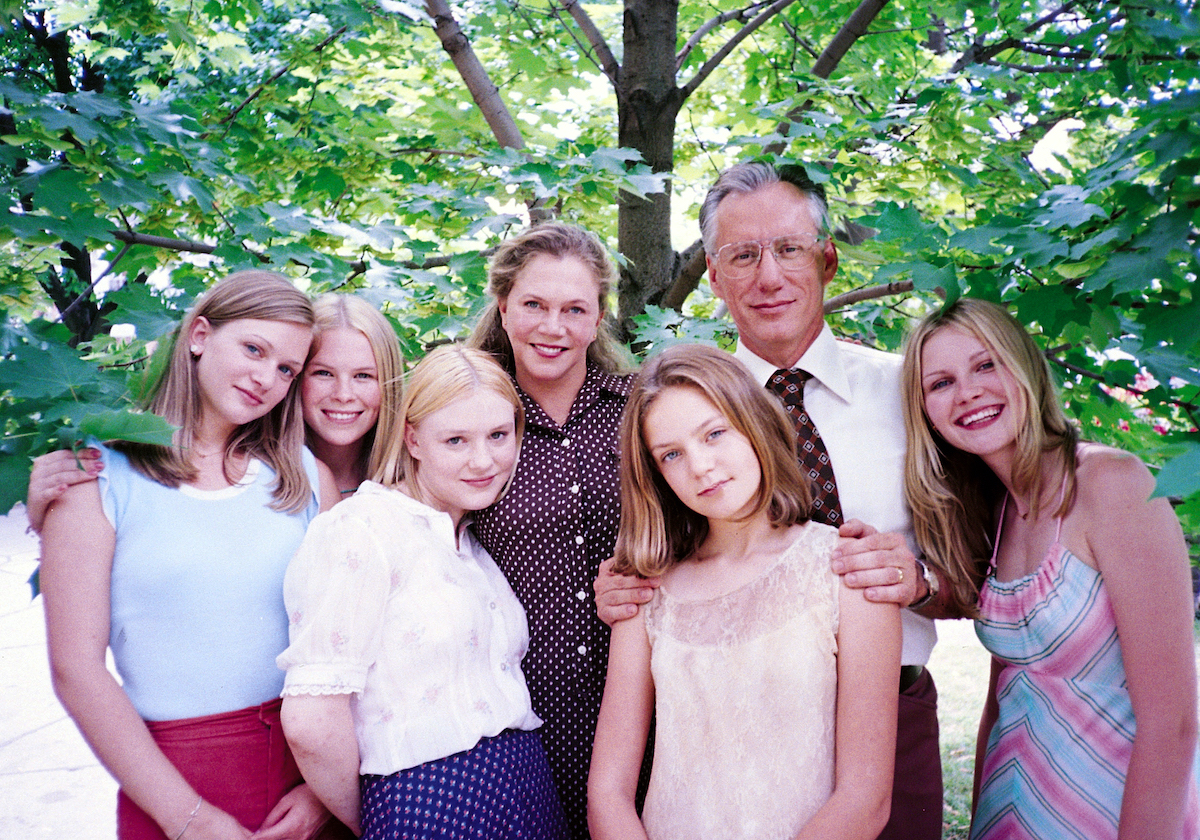

The Virgin Suicides served as Sofia Coppola’s directorial introduction to the world. Based on Jeffrey Eugenides’s 1993 novel of the same name, Coppola also adapted the screenplay, a seemingly personal passion project of suburban ennui and coming-of-age turmoil. In 1970s Michigan, a quintet of teenage girls live under the strict rule of their Catholic parents (Kathleen Turner, James Woods), quietly exploring fantasies—both sexual and suicidal—that stem from a life of denial and repression.

The blonde girls—Lux (Kirsten Dunst), Mary (AJ Cook), Cecilia (Hannah R. Hall), Therese (Leslie Hayman), and Bonnie (Chelsea Swain)—share more than a passing similarity to each other. They dress similarly, smile similarly, and behave like a single organism with gestures and nods providing coded messages to each other. Much in the way identical twins often make up their own languages, the Lisbon girls also seem to understand each other in a way nobody else ever could.

Their parents are flustered and the neighbourhood boys utterly beguiled. The boys’ reflections as adults, looking upon their childhood memories, serve as the narration for the film. “It didn’t matter in the end how old they had been, or that they were girls”, Giovanni Ribisi’s melancholy’s voice recalls. “But only that we had loved them”. They seem to have little understanding now of who these girls were; only how the girls made them feel. Such is the relationship one has with a person who contracts when you reach out to them; Coppola’s film tries to understand just why these people always remain just out of reach.

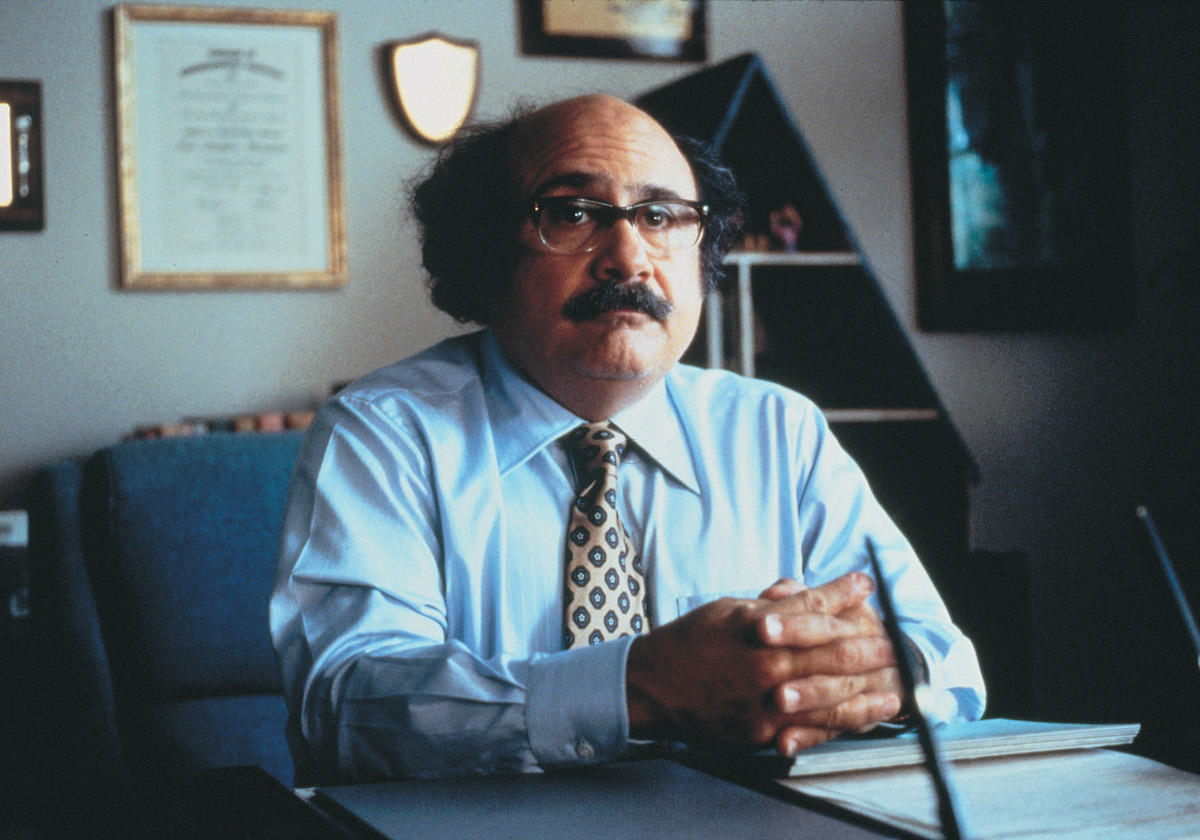

The doctors don’t get it. After a suicide attempt in the family bathtub, a recuperating Cecilia responds “obviously, doctor, you’ve never been a 13-year-old girl.” Coppola services her characters by taking them seriously. These aren’t the clichéd teenage girls that populated late-1990s cinema, often depicted in films made by men. They’re instead romantic, mysterious, almost completely unreachable, and transplanted as if they came from another century.

Taking teenage problems seriously has often resulted in some of film’s most important adolescent works, from Buñuel’s crushing Los Olvidados (1950), to Amy Heckerling’s blunt and heartfelt Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), and Penelope Spheeris’ fiery Suburbia (1984). The latter two contributing to a larger culture of brilliant teen films written and/or directed by women, including Heckerling’s own Clueless (1995) and the Tina Fey-scripted Mean Girls (2004).

The Virgin Suicides sits comfortably alongside those films as a piece of art made by a woman that tackles the problems of teenage girls with the weight and dramatic inquiry called for. This is cleverly reinforced via the film’s narration; if the boys haven’t forgotten the sisters, all these decades later, then how can they be dismissed as a bunch of kids who are “looking for attention”, as the doctors claim.

However, even with the ever-present spectre of death hanging over things, Coppola is playful with proceedings. The film floats with an effervescence that never lets its feet touch the ground. The suburbia the girls live in is golden during daytime, the colours vibrant on an older film stock which makes it all look like an impossible memory. This Blue Velvet (1984)-style suburbia is evoked with plump neighbours watering their grass and the sun being kept out by overhanging trees. Greenery is everywhere. But rather than sinister, it’s sedated.

Suburban malaise wasn’t an alien subject in the ’90s. When the American middle classes thrived and the topic of the day seemed often to be ‘I have what I want, so why am I still unhappy?’, it wasn’t long before films began to catch on to US inertia, and dramatised it to varying degrees of success. While the flawed American Beauty (1999) was riddled with reductiveness, The Virgin Suicides instead makes an excellent bedfellow with Todd Hayne’s Safe (1995), which looked at middle-class mania in the form of hypochondria and medicine. Both The Virgin Suicides and Safe went further and said more, because their makers where particularly keyed in to American anxiety.

Put plainly, everything sucked, but everyone already knew that. By 1999, it simply wasn’t enough for a film to suggest the once novel concept that suburbia isn’t as perfect as it appears. Instead, what Safe and The Virgin Suicides did was to bask in this discomfiting world, wherein deeper questions could truly be explored. Without a sneering condescension, Coppola found space to go deeper than American Beauty ever could.

Nowhere is there a clearer parallel of the films’ successes and failures than with the parental roles. American Beauty was, at the time, seen by many as the film about middle-class America. Perhaps that hyperbole allowed people to overlook the ludicrous soap opera-like thread in that film which saw a murderous gay nazi living next door. Looking then at Coppola’s film, it becomes clear just what a sophisticated and complex level she was working on. Mr and Mrs Lisbon may be strict Catholics who struggle to let their daughters even walk to school alone, but Coppola finds abundant space for their nuances.

James Woods is cast excellently against type; his Mr Lisbon is bumbling, sweet, and just wants to show off his World War II model airplanes to his daughter’s bored friends. Underneath that friendliness there’s a deep and controlling fear, but Coppola affords the opportunity to decide which of those halves is the true Mr Lisbon. As Mrs Lisbon, Kathleen Turner is painfully good. She channels her delightful performance in John Waters’ Serial Mom (1994) here for supreme suburban genteelness. But somewhere under the mask isn’t murderousness or cruelty, but a pervasive sadness and fear. So where does that leave the daughters? As total enigmas.

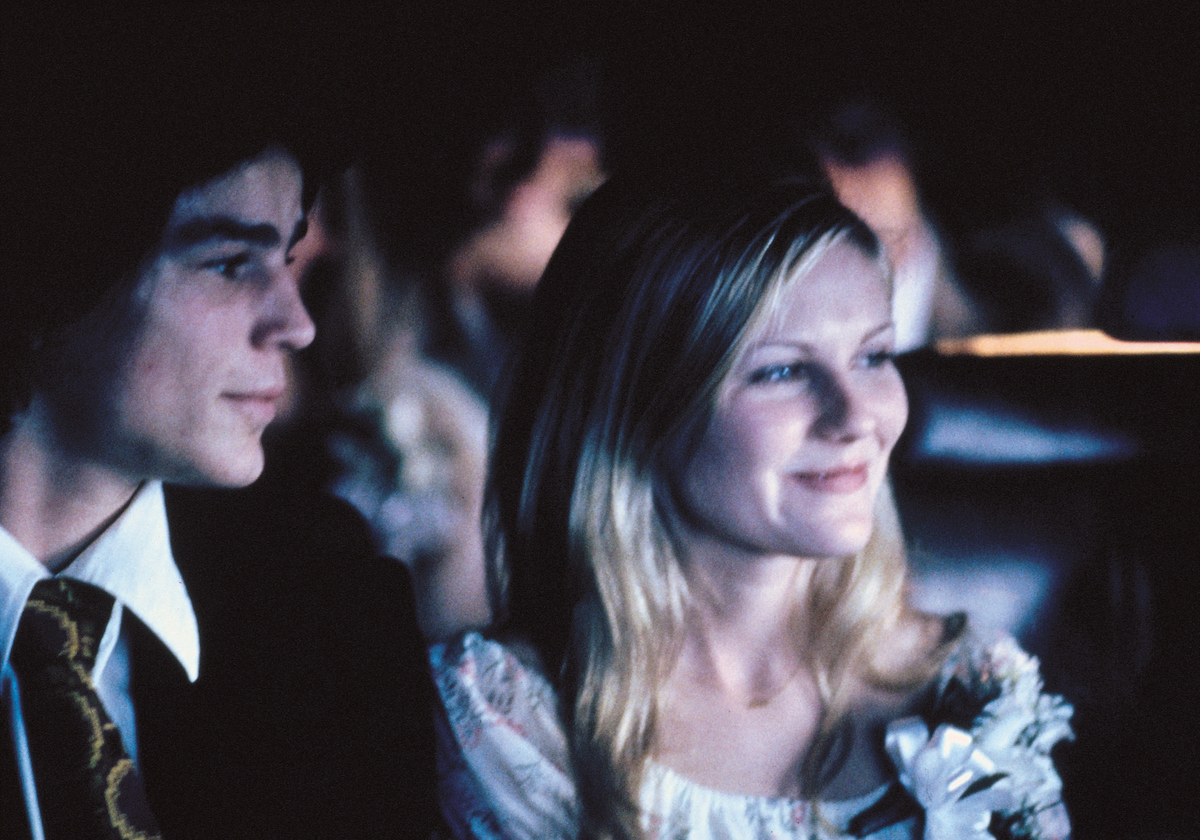

It’s unfathomably brave that Coppola so stridently keeps the Lisbon girls out of our reach. We understand them—if we do at all —by the perfumes scattered across their dressers, by hand-scrawled notes passed to boys, by the squeals of delight (which almost give the game away) when they are permitted to attend a dance. They speak very little, and they keep it simple, monotone. Their gestures are words—stray feet under the dinner table towards the crotches of guests, and smiles from across the room to confused teen boys.

Kirsten Dunst (Interview with the Vampire) is particularly intriguing, giving us alternating moments of reality and performance, so that we don’t fully know who Lux actually is. She wears an expression that seems to say she knows more than you do at any given time. Coppola loads her female characters–especially Lux—with total confidence, and a strange ability to lure the boys in and push them away at the same time. They have a magic which Coppola relishes.

The film itself responds to their seeming omniscience. Hand-scrawled lettering fills up the screen for the title-cards; the girls fade in and out over images of the sky, and they dance through wheat fields. The mornings are an intensely lobotomised blue, the nights are filled with cricket song. Here we find ourselves in a place that you would not call simply ‘the suburbs’, but instead something a little more magical, perhaps a place that’s visually affected by the girls who live there. The score, by the great french electronic duo Air, provides another layer of dreaminess, as Coppola dissolves slowly between images. This is their world, it seems to say.

If only things were that simple. As the boys of the neighbourhood get closer to the Lisbon sisters, the girls begin to grow uncomfortable. An awkward party in their basement, chaperoned by their parents, sees Cecilia the focus of a group of kids who, clearly, she is entirely estranged from. There’s punch, balloons, boys in suits and awkward chatter. None of this feels like them. It ends with one of the sisters excusing themselves, walking upstairs, and jumping out of her bedroom window to her death, her corpse held in tableau by her father in a moment of high drama. It is clear now that this isn’t a cult. It’s performance art.

Everything the Lisbon sisters do seems designed to evoke questions. Like Harold’s character from Harold and Maude (1971) who fakes his death in increasingly absurd scenarios, the Lisbon sisters need witnesses. They need, for their own sanity, to use their status as caged animals as a weapon, to send a message to their peers. What that message is may take an eternity to decode. And faking a suicide is child’s play; these are teenagers, and they know they must go a step further. There’s no line between art and reality anymore, nor fantasy and life.

If Coppola’s films are often power plays (2017’s The Beguiled being the clearest and most relevant comparison point here), then she certainly elicits a cinematic ecstasy from the inversion of power. Things grow increasingly tricky as the film progresses. The boys find the diaries of the sisters, and pore over the smallest details. It is then that we see the images of the girls frolicking through wheat fields and riding on boats alongside whales. The image quality changes here to what looks like a video camera—are we seeing memories, or the boys’ imaginations?

By transferring the film’s language to an entirely different format, Coppola elegantly exposes the subjectivity of the narrator, and we begin to wonder who really holds the power. By not letting the boys into their lives, the Lisbon girls have kept them in perpetual orbit. But by breaking into their diaries, the boys shatter the illusion; the girls memories and inner lives become spoiled, contorted and chewed up like dogs over a bone. How can you maintain control of your life after someone has forced their way in?

Even with the performance that the girls give their neighbours, the undercurrent of sadness is palpable. The recollected nature of the film gives memory and time a slippery quality, as if the girls are dead long before the film even begins. It’s in the death and melancholy that Coppola really makes Virgin Suicides sing, especially when juxtaposed with the airy, dreamlike visuals.

It’s a stunning work. Though 1970s-set, it couldn’t be more pre-millennial. On the cusp of a new millennium, Virgin Suicides takes in the last century of self-imposed imprisonment, and sends a much deserved salute to the girls who are remembered wrongly by men, the people who didn’t have a choice and so turned their existence into a performance. The miraculous thing is that there is no dourness to be found; it all feels like a stunning revelation, a true, rapturous epiphany that accompanies a first love. It remains, as a result, one of the most hauntingly romantic films in American cinema.

USA | 1999 | 97 MINUTES | COLOUR | ENGLISH

This new release from Studio Canal is one of the finest 4K restorations I’ve seen. The colours are phenomenal with the film trading in rich sunshine-oranges and cold sterile blues. All areas of the colour spectrum pop vividly in this transfer, while the crisp image is just right, leaving a healthy film grain in tact. The sound design of the film is meticulous, and everything—from the chirping crickets to that gorgeous score by Air sounds brilliant and full.

director: Sofia Coppola.

writer: Sofia Coppola (based on the novel by Jeffrey Eugenides).

starring: James Woods, AJ Cook, Kathleen Turner, Kirsten Dunst Josh Hartnett, Scott Glenn, Michael Paré, Jonathan Tucker & Danny DeVito.