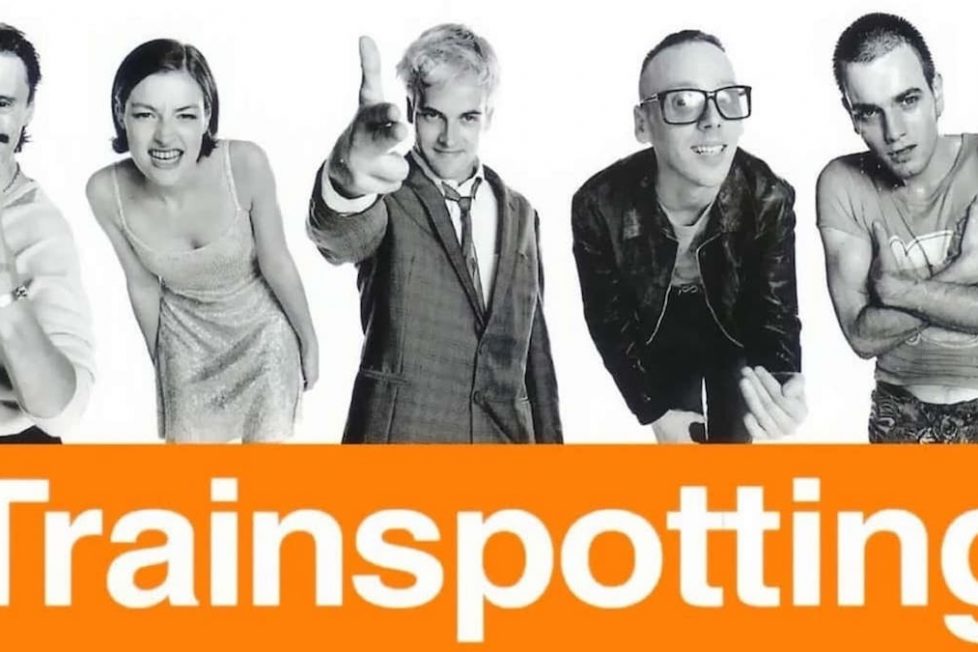

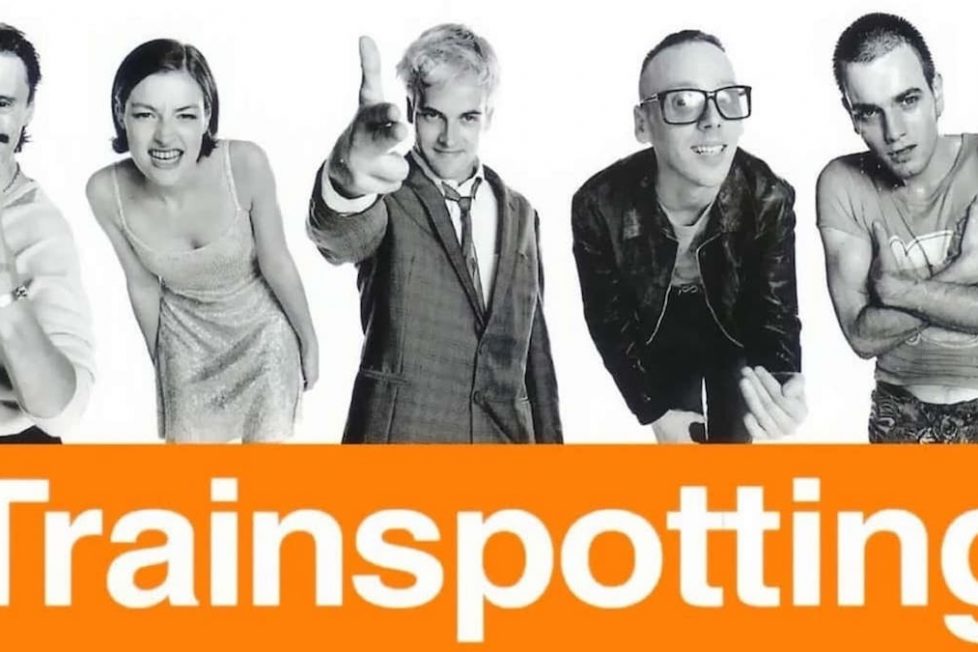

TRAINSPOTTING (1996)

A young man immersed in the Edinburgh drug scene, tries to clean himself up, despite the allure of the drugs and influence of friends.

A young man immersed in the Edinburgh drug scene, tries to clean himself up, despite the allure of the drugs and influence of friends.

For a film dealing with addiction, AIDS, the death of a baby, psychotically enraged violence, and the vilest toilet imaginable, Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting is anything but grittily realistic. Indeed, even when handling grim subject matter, it often has the same air of carefree fantasy as his later Slumdog Millionaire (2008) and Yesterday (2019). Though drugs in general, and heroin specifically, are never far away throughout the film, it’s a mistake to see Trainspotting as about drugs in any meaningful way. Or, indeed, as exclusively about anything in particular, and it’s certainly not pointing us toward any definitive conclusion.

The film does, on balance, sound a note of caution. The voiceover passage where Renton (Ewan McGregor) declares that “people think [drug use] is all about misery and desperation and death… but what they forget is the pleasure of it”, is more than balanced by a later scene, Trainspotting’s darkest, where an addict’s baby is found dead in her crib. Here, Renton wishes “I could think of something to say, something sympathetic, something human”, but after a silence all he can think of is: “I’m cooking up.”

Mostly, though, Boyle is interested in simply presenting scenes from the lives of his four central characters: Renton, Spud (Ewen Bremner), Sick Boy (Jonny Lee Miller), all three of them gentle users, and the vicious non-user Begbie (Robert Carlyle). The film opens with a terrifically kinetic scene of the first three running from store detectives through the Edinburgh streets (they’re stealing to feed their habit), to the accompaniment of Renton’s famous “choose life” monologue, ironically mocking the “respectable” lifestyles that society tells them they ought to be pursuing instead.

This is followed by more scenes chosen to convey flavour rather than any specific narrative, interspersed with much slower-moving interludes with Renton getting high. And it’s this slice-of-life approach which gives Trainspotting much of its power and conviction. While there are several storylines (becoming darker as the film progresses, including Renton’s attempts to detox, his new job, a friend’s death, and the four young men’s attempt to get rich on a drug deal), they’re little more than excuses for portraying the characters, both alone and together. What’s important in Trainspotting is never what happens over the timespan of weeks or months, but what’s happening in the here and now—a structural reflection of the addict’s worldview, perhaps.

This makes it a perfect vehicle for Boyle’s decidedly unreal visual approach. Trainspotting feels very much like a product of the French New Wave transported to Edinburgh in the mid-1990s. Even scenes that are superficially realistic often being given a mannered twist. For example, by shooting characters from behind or below, and repeatedly setting them against large fields of a single colour. Now and again the flashy touches that became so associated with Boyle are evident—like a fantasised tacky TV quiz show where all the questions seem to be about the bio-mechanisms of HIV, and Boyle’s fondness for on-screen text is manifest when the word “Toilet” on a door is turned into “The Worst Toilet in Scotland”. Graffiti also serves the same function at times.

Still, it’s always well-thought-out rather than self-indulgent. When Renton dives down the world’s worst toilet, o retrieve some heroin suppositories, and emerges into clear water, it’s still a naval mine that he swims past rather than a school of pretty tropical fish. That unexpected little note of menace is perfect. Later, when Renton seems to sink many feet into a carpet after receiving a fix from Mother Superior (Peter Mullan), we soon see that the red colour of the carpet is in fact the red of a hospital trolley on which Renton’s lying after Mother Superior worries that he’s overdosed.

The most important departure from realism, though, is in the language. Dialogue is frequently arch, almost Ortonesque (“He’s always been lacking in moral fibre.”—“He knows a lot about Sean Connery.”—“That’s hardly a substitute.”). And then there’s Renton’s pervasive voiceover, which, like the rest of John Hodge’s screenplay, is also a significant departure from Irvine Welsh’s 1993 source novel. It was felt that the unrelenting Scottish idiom of the book would be incomprehensible to audiences. Not only is the voiceover self-consciously non0naturalistic (for example, with the almost rhapsodic “choose life” oration, or with Renton saying “dot dot dot” to indicate an ellipsis), it puts the emphasis of the film very firmly on McGregor’s character even when the action’s more concerned with others.

Due to this artificiality in the script a lot of the acting has to be physical, and the central quartet carry it off admirably. McGregor underplays stylishly, giving the impression of always knowing a little more than he’s letting on and keeping himself a bit distinct from the others while no more able to resist the coveted substances than they are. (“The streets are awash with drugs you can have for unhappiness and pain, and we took them all.”) Bremner manages to make Spud both comically grotesque and utterly sympathetic; Miller’s Sick Boy, always dressed to the nines, is intriguingly inscrutable; Carlyle’s Begbie is simply terrifying, an ever-present reminder of the brutal realities which the drugs mostly soften.

Mullan is also convincing as Mother Superior, as is Kelly Macdonald playing a schoolgirl with whom Renton sleeps while unaware of her age, and Keith Allen as a London dealer whose politeness does nothing to mask his obvious ruthlessness. A compelling soundtrack accompanies all these performances, often obliterating diegetic sound and ranging from Bizet’s “Carmen” for the toilet and detox sequences to Leftfield, Joy Division, Iggy Pop, Brian Eno, and Blur. Enough that two tie-in albums were released, in fact.

Shot on a small budget of less than £2M, Trainspotting was a notable success and returned this investment many times over. It became one of the most talked-about films of the year in the UK, confirming Boyle as a major director and McGregor as a big star.

Critical reception was enthusiastic. Janet Maslin in The New York Times felt that “dark as its subject matter is, this film manages the incredible trick of remaining jubilant and fresh”, while Derek Malcom in The Guardian considered it “an extraordinary achievement and a breakthrough British film, shot by Brian Tufano with real resource, fashioned more imaginatively than Shallow Grave by Boyle, less determined to please, and acted out with a freedom of expression that’s often astonishing.”

A sequel, T2 Trainspotting (2017), was a thoughtful follow-up revisiting the characters as older men, with a surprising development for Bremner’s Spud in particular. But for most Trainspotting fans it’ll always be the quartet from Boyle’s original they remember. Scheming and arguing and sounding off and rolling around the floor, just like the baby who provides the film with its bleakest moment, they’re figures of fun, irritation, tragedy, and strangely believable despite the film itself not pretending to realism at all.

UK | 1996 | 93 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Danny Boyle.

writer: John Hodge (based on the novel by Irvine Welsh).

starring: Ewan McGregor, Ewen Bremner, Jonny Lee Miller & Robert Carlyle.