PAIN HUSTLERS (2023)

A struggling young woman finds rapid success marketing opioids for a dubious pharmaceutical company.

A struggling young woman finds rapid success marketing opioids for a dubious pharmaceutical company.

Netflix’s latest addition to the growing body of screen drama about the opioid crisis, Pain Hustlers, comes with promising credentials. Director David Yates helmed the highly regarded BBC political series State of Play (2003), though most of his film work has been in the Harry Potter and Fantastic Beasts franchises. Screenwriter Wells Tower is a celebrated young author of fiction and journalism, and Evan Hughes’s book, on which the film is based, has been positively received.

Despite the recent influx of productions on the opioid issue, including acclaimed documentaries and fictional works like Hulu’s Dopesick (2021), the flawed but interesting Cherry (2021), Netflix’s own recent Painkiller (2023), and even its adaptation of The Fall of the House of Usher (2023), the subject has yet to receive a definitive treatment.

Pain Hustlers isn’t it, though. Like many films about sprawling real-life events, it struggles to balance its personal and “issue” storylines. The former is more successful, which may explain why it’s been so difficult to encapsulate the entire opioid crisis in a single film.

Still, despite its structural and emphasis issues, this intriguing and watchable tale is well-told moment by moment, even if it doesn’t satisfy as a whole. Vivid performances bring it to life.

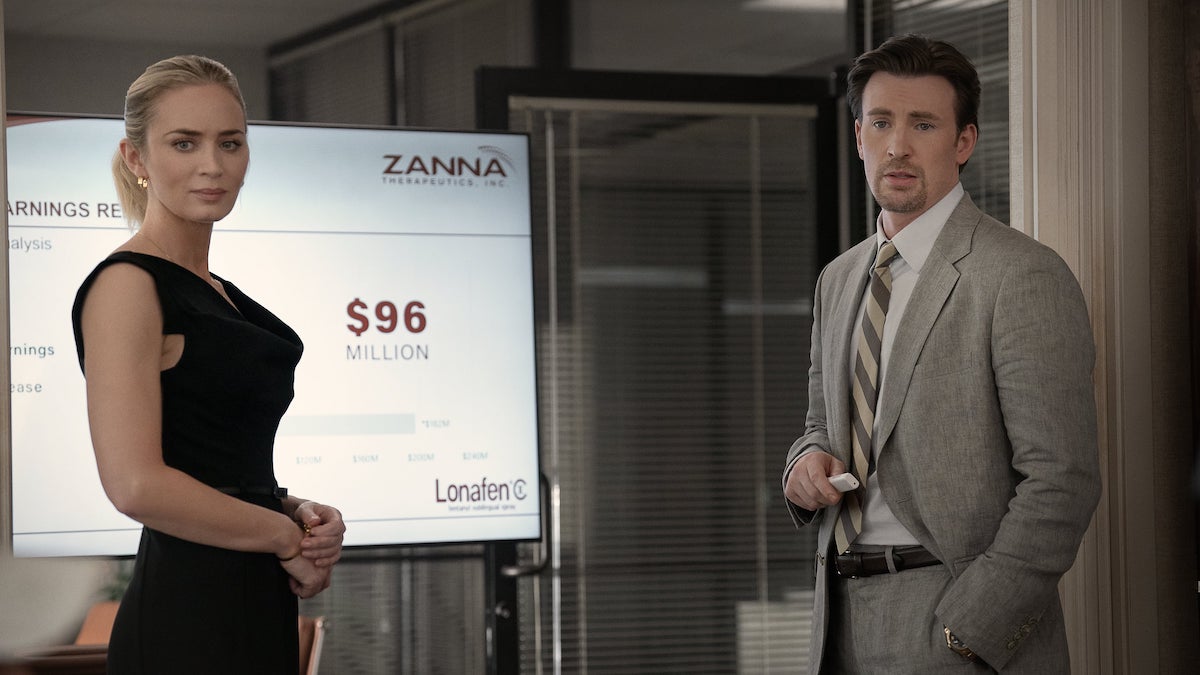

It’s 2011 and approaching the height, not the beginning, of the opioid crisis—though you wouldn’t necessarily guess that from the movie. Liza (Emily Blunt), a stripper in Florida, meets Pete (Chris Evans) at the club, who offers her a job at his pharmaceutical company. Is he serious, or is he just another man trying to impress? Liza’s worsening financial situation drives her to find out, as she reconnects with Pete. With dizzying speed and the help of a heavily embellished resume, she lands a job on the sales team at Zanna, a company based on the real-life Insys (the subject of Hughes’s book).

Like Insys, Zanna’s main product is a fentanyl formulation, Lonafen (Insys’s was Subsys), that works faster than the competition to relieve severe pain. The innovation is in the delivery mechanism (spraying under the tongue), not the drug itself.

Unlike what some coverage of Pain Hustlers suggests, Zanna is emphatically not Big Pharma. This is a large part of the point. Zanna is a small, sketchy startup with hardly any revenue and a cowboy attitude that allows management to reject the idea of setting up a compliance team. Big Pharma shapes the rules through legions of Washington lobbyists; small pharma like Zanna tries to sneak under and around the rules.

Liza may be completely unqualified, but she isn’t incompetent. When sent out to persuade doctors to prescribe Zanna’s drug instead of the competition, she quickly signs them up, increasing the previously struggling company’s market share and earning enough to move out of the crummy motel where she and her daughter had been lodging.

But internal tensions within the company won’t go away, and nor will the spectre of legal problems. For all that its law-breaking is repeatedly shrugged off by insiders as “67 in a 65”—referring to minor infractions in speed limit zones—the federal authorities (responsible for pharmaceuticals regulation) are becoming interested in its activities.

Their particular concerns include the bribes that Zanna offers to doctors to prescribe its products (often in the form of fees for “speaking” at barely existent “conferences”); an astonishingly small number of physicians (about 170) were responsible for a substantial proportion of synthetic opioid prescriptions (about 30%), so targeting individuals was lucrative for the drug companies.

Zanna in Pain Hustlers also breaks the law by encouraging “off-label” prescribing, or using a drug for something other than its approved purpose. For example, Lonafen is only licensed to treat cancer pain, so prescribing it for back pain is illegal. However, the company actively encourages this practice, and Liza’s colleagues resist her attempts to get the company back on the straight and narrow, even though she knows this situation cannot continue indefinitely.

I happen to cover the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the pharma regulator, for a living (among other topics), so it’s forgivable that I find all this nerdishly interesting, but I suspect most viewers will find Liza herself more compelling than the storyline. Blunt is unsurprisingly persuasive in the role, never stereotyping Liza but bringing the mother, daughter, enthusiastic sales star, dynamic team leader, and doubt-riddled executive with a conscience together into one human being.

Catherine O’Hara (Home Alone) shines as Liza’s charming and willful mother; Andy Garcia is unrecognizable as the increasingly eccentric company founder; Brian d’Arcy James excels in the ambiguous role of a pain doctor who may be innocent or corrupt; Jay Duplass is superb as a Zanna exec jealous of Liza’s success; and Amit Shah is noteworthy as another executive nervous about the company’s misdeeds.

Yates’s direction and Tower’s writing are straightforward but effective, propelling the story forward along its predictable path while giving key scenes enough room for the characters and issues to develop. They also add just enough unexpected twists to keep the audience engaged. However, Pain Hustlers is ultimately limited by what it doesn’t do, does poorly, or does at the wrong time.

For example, its presentation of actual victims of opioids is so cursory that it would have been better omitted. Similarly, by focusing exclusively on the story of Liza at Zanna, the film fails to convey that this is just one relatively small company that arrived relatively late in the development of the opioid crisis (a criticism that has also been levelled at the book). The movie ignores systemic issues in US healthcare, such as the way funding can incentivize the use of drugs, and veers dangerously close to implying that everything might have been fine if not for this one rogue company.

Zanna’s sins aren’t adequately distinguished either. Off-label prescribing is against the rules, but many people will sympathize with Zanna’s argument that “pain is pain” and that its cancer drug should be available to patients with other conditions. Far more serious, however, is Zanna’s reliance on a single study to support its claims of non-addictiveness, a study that is revealed at the very end to be fraudulent.

Although the movie is convincing when it focuses on a woman striving in a competitive corporate world, we don’t see enough of Liza Blunt to fully understand her. And while Pain Hustlers provides well-explained details, it fails to offer a satisfying big-picture view of the issues it explores. Audiences will leave the film with little more understanding than they had at the start, despite picking up a few nuggets of information along the way.

And so, by failing to fully commit to either its central character or its themes, Pain Hustlers fails to deliver the powerful punch it clearly strives for.

UK • USA | 2023 | 122 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: David Yates.

writer: Wells Tower (based on the book ‘The Hard Sell: Crime and Punishment at an Opioid Startup’ by Evan Hughes).

starring: Emily Blunt, Chris Evans, Catherine O’Hara, Andy Garcia & Brian d’Arcy James.