TONY ARZENTA (1973)

A mob hitman wants to retire, but his bosses don't think that's a good idea...

A mob hitman wants to retire, but his bosses don't think that's a good idea...

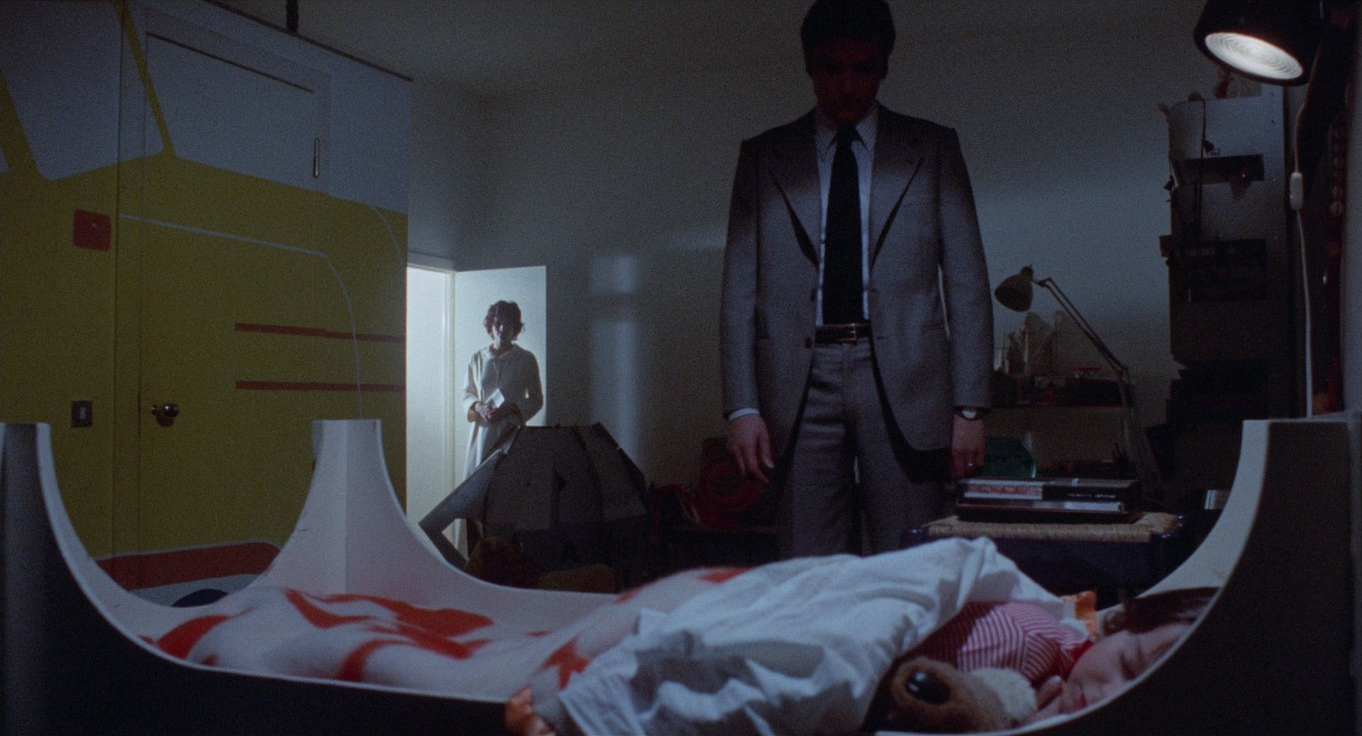

The pre-title vignette establishes an unremarkable domestic setting for Tony Arzenta (Alain Delon) and his family. Their chic, design-conscious, and comfortably middle-class apartment is the venue for his young son’s birthday party. Yet Tony seems distracted and detached, checking his watch. Before leaving, he rather ominously says to the boy, “Happy birthday, young man, and may you have many, many more…” Perhaps it’s Delon’s shrewdly economical performance or the fact we’re watching an early-1970s Italian crime thriller, but within minutes, we’re already searching for clues and trying to guess what’s amiss.

So, I was already hooked by the time the evocative strains of Gianni Ferrio’s title song, “L’appuntamento” (The Appointment), with vocals by Ornella Vanoni, came in over the gorgeously shot night-driving opening credits. Here, we have a meeting of superior Italian cinematic talent. Ferrio is one of the few important composers responsible for creating the mood so intrinsic to the films of the era. He stands alongside Fabio Frizzi, Ennio Morricone, Bruno Nicolai, Nora Orlandi, and the prog-rock band Goblin. Though some might categorise it as loungecore, the importance of Ferrio’s superlative score, elevating Tony Arzenta throughout, can’t be overstated. Vanoni, one of Italy’s most long-established and revered popular singers, with well over 100 releases to her name, has racked up over 65 million sales since her debut in the early-1960s.

The cinematography is by Silvano Ippoliti, who is a master of the low-light, night shooting that became emblematic of 1970s Euro-cinema. In the late-1960s, the tendency to flat-light everything fell from favour with Italian filmmakers. Instead, they adopted a more naturalistic approach, often relying on available illumination, with just a few well-placed lamps to add a visual drama of light and shadow—perfectly suited to the increasingly baroque themes.

Here, Ippoliti continues to create varied textures from scene to scene, responding to different locations and atmospheric conditions. He takes advantage of fog and torrential rain, which seem sympathetic to the psychological narrative—though I presume they were unplanned. His notable contributions had already included Sergio Corbucci’s bleak Western The Great Silence (1968), Riccardo Freda’s inferior giallo The Iguana with the Tongue of Fire (1971), and Silvio Amadio’s superior film Smile Before Death (1972).

The haunting theme tune works well in tandem with these subdued late-night visuals, effectively creating a melancholic mood. However, with Duccio Tessari at the helm as director, we know that the mood will be shattered by visceral violence and heart-pounding action sooner or later.

Until recently, Duccio Tessari was little known to 21st-century audiences. Inexcusably forgotten despite being a seminal and consistently consummate director, his career spanned five decades and tackled a wide range of genres. It was probably about ten years ago that I first came across his name, having seen the restored re-release of his memorably provocative giallo, The Bloodstained Butterfly (1971). More recently, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed his highly satisfying Italian Western duology, A Pistol for Ringo and The Return of Ringo (both 1965).

The director understands the pacing of a thriller, and his visual flair keeps things interesting for Tony Arzenta. He employs a variety of shots: ponderous long takes contrasted with rapid edits; expansive long shots and close-ups; deep focus; and skilful use of pan and zoom. He also elicits strong performances from a very capable ensemble cast, elevating the functional, potentially dull script written by Franco Verucci with assistance from fellow veteran genre writer Ugo Liberatore and newcomer Roberto Gandus. Verucci had previously been involved in the unpredictable story for the unusual Euro-western Wrath of the Wind (1970), and Liberatore had, early in his career, contributed to the classic gothic horror Mill of the Stone Women (1960).

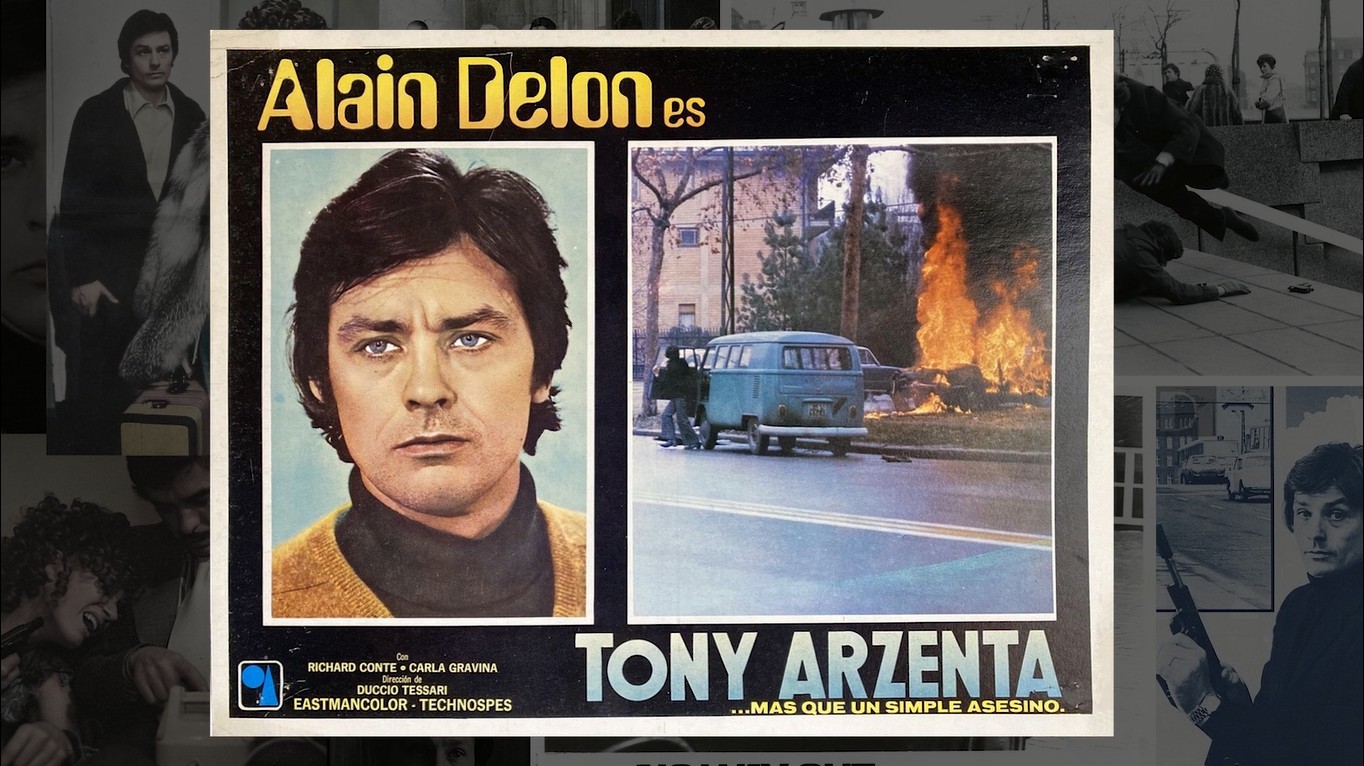

Perfectly cast in the lead role, Alain Delon portrays Tony Arzenta as a character very similar to Jeff Costello in Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï (1967). This could almost be a sequel—if it were possible for the character to return and adopt a new identity. Here, however, we glimpse the human side of a hitman, or perhaps see an earlier version of the man before he abandoned his humanity. During one hit, when an uninvolved henchman stumbles upon the scene, Tony offers a small shrug of apology before clinically eliminating the hapless witness—a concession Costello would never make.

Whilst Costello remained cool and stoic to the very end—when we might have glimpsed the merest flicker of emotion—Arzenta appears to value his own life and the lives of his family. He’s certainly a loving father, and the reason he wants to extricate himself from the hired assassin business is so he can be there for his son and not groom him for the same lifestyle. The scene where Tony returns home after the efficient execution and says goodnight to his sleeping child will be mirrored by a later scene when he visits his ailing father—both portends of impending death.

When Tony tells his Mafia contact, Nick Gusto (Richard Conte), that the contract was his last job for the mob, he’s warned in no uncertain terms that the only way out of the business is feet first. Tony remains steadfast and Gusto agrees to put in a good word and sound out his associates. This was a late-career role for Richard Conte, who was fresh from playing Barzini in The Godfather (1972). Here, he delivers a nuanced performance as a callous mobster who accepts the inevitable, even though he might just be wrestling with his conscience at times. It seems he’s happy to manipulate others to do the dirty work he can’t bring himself to do.

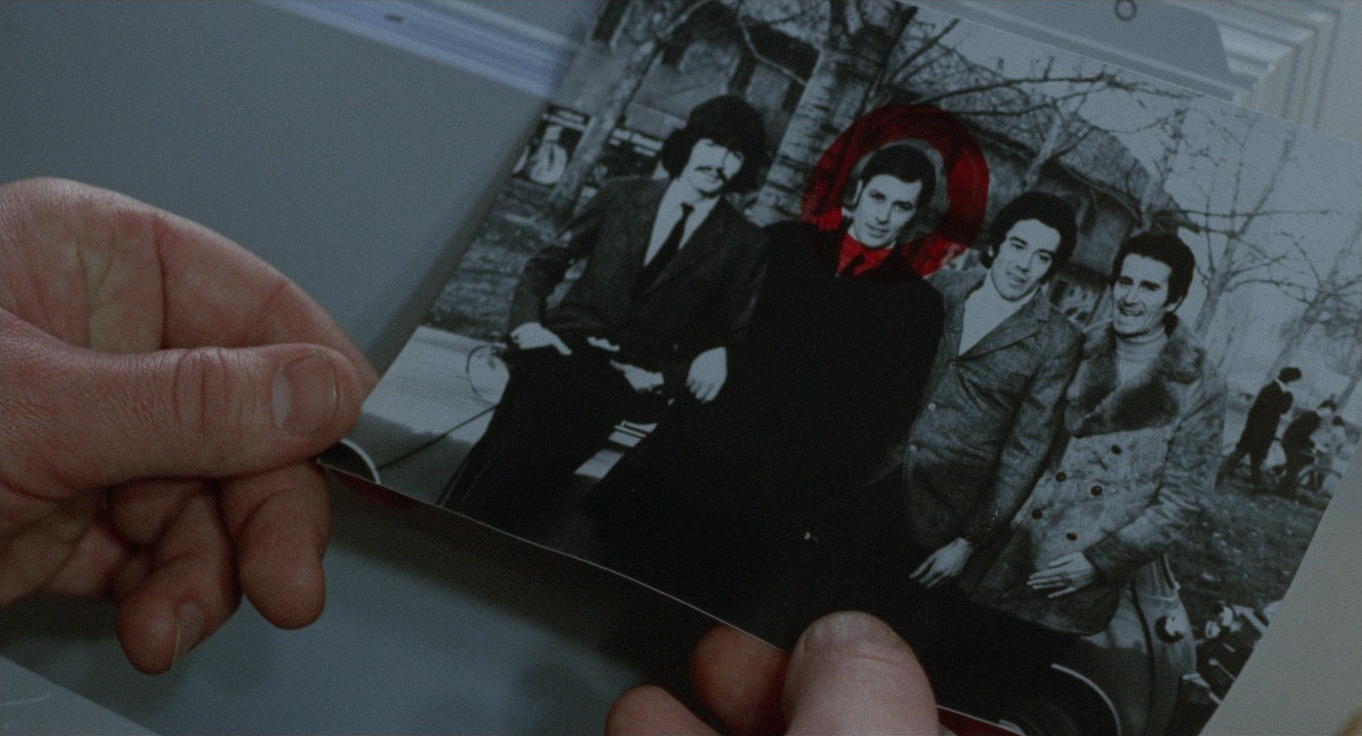

Arzenta’s associates see him as an unacceptable liability and want him silenced permanently, leaving that responsibility to Gusto. However, the assassin hired to kill Arzenta is nowhere near clinically efficient, and a car bomb tragically kills Tony’s wife and son in error. This comes as no surprise and is part of the necessary set-up to transition from a Eurocrime thriller into a revenge film as Tony Arzenta hunts down each of his former clients one by one. The film now begins to resemble a reverse giallo—instead of baroque set pieces where an unknown killer stalks their victims, we’re with the killer, and even though he began as one of the bad guys, we’re certainly rooting for him as he delivers some slickly staged, brutal executions.

Arzenta also becomes a catalyst for a ruthless power struggle between the dwindling cartel bosses as they redistribute their various rackets and territories. Indeed, he’s doing such a good job of despatching bad guys that an undercover Interpol operative, Montani (Silvano Tranquilli), tries to recruit him. It seems Interpol is prepared to turn a blind eye as long as he keeps on killing the gangsters who place themselves above the law.

Tranquilli will be a familiar face to fans of Italian pulp cinema. He’d previously worked with Tessari, playing a Police Inspector in The Bloodstained Butterfly. He’s also the male lead in Silvio Amadio’s Smile Before Death opposite Rosalba Neri, another fan favourite who appears in an equally brief cameo as the wife of Rocco Cutitta (Lino Troisi)—a decidedly nasty piece of work seen cradling his young son, similar in age to Tony’s boy. There are several other notable cameos, including Anton Diffring, who always brings gravitas and has no problem playing the ruthless boss of the Scandinavian territories.

Carla Gravina is fine in the female lead and takes a beating so severe it was cut from the international print, though it’s restored here and there’s a clear influence from Stanley Kubrick’s treatment of a similar scene of ultraviolence in A Clockwork Orange (1971). Another scene of male-on-female brutality remains uncut when a prostitute (Erika Blanc) is beaten bloody by her pimp. Although Tony witnesses this appalling violence, he doesn’t intervene. But does help the unfortunate woman afterwards. This allows us to see a chink in his armour of indifference and it’s not the only time succumbing to his better nature lands him into trouble and results in another amazing car chase.

The production design by Lorenzo Baraldi is a veritable showcase of period design and décor, a delight for those who thrill from spotting a vintage 1960s Ericofon. The interiors are all well-chosen and exploited effectively by Tessari’s inventive camera angles. These angles often place visually interesting items in the foreground, so that a plastic radio or a modern piece of desk art might fill half the frame, dwarfing the actors and making them seem distant even in enclosed spaces. This technique also elevates mundane items to grand proportions, so that a telephone becomes the set itself rather than a mere detail. Although these choices often seem purely stylistic, they can also have a subtle narrative role to play. For example, the Arnulf Hoffmann kinetic sculpture in the hall of the Arzenta apartment is moving when his son is present, implying the boy can’t resist setting it off. But later, when Tony is alone, the three-pendulum arrangement is still, lifeless, just like the boy.

One of the main selling points at the time was the jet-setting plot, which whisks the action from Milan to Paris, then Copenhagen and back again. Tessari uses the various locations to drive the narrative forward and contrasts picturesque landmarks with seedy club interiors, furnished with red velvet and mirrors that could be found anywhere. These, in turn, are contrasted with even less salubrious places like scrapyards, where a particularly brutal torture scene takes place. Now, I don’t think I’d seen Tony Arzenta before, yet this seemed familiar…

Chases, beatings, and interrogations in scrapyards are a common feature of Euro-crime movies for several reasons. Firstly, the stacked car wrecks are immediately menacing, with sharp, jagged edges and contorted bodies that speak of death and injury. They silently imply the fate of those dragged from road accidents, as well as the possible state the victim may soon resemble.

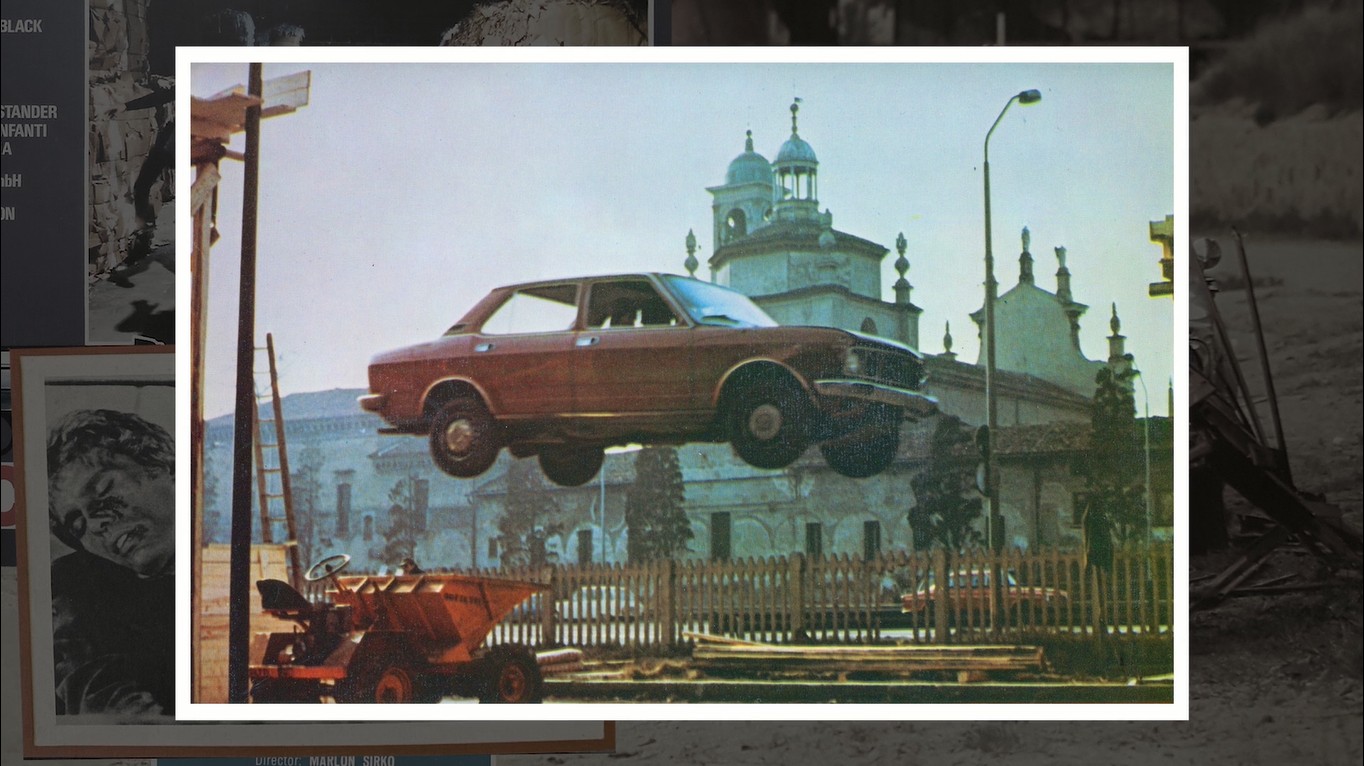

There’s also a simple reason of economy and convenience. Such films inevitably feature at least one car chase where cars end up bashed and battered. The chase might begin with pristine models, but soon after the action kicks in, they’ll run through a barrier, prang another vehicle, or career through some shrubbery. This is because the budgets don’t stretch to wrecking perfectly good cars, many of which belong to the cast or crew. Soon after the chase starts, they’re substituted for write-offs sourced from the scrapyard and given a cosmetic makeover to match the model and colour. They are then used and abused before returning to the scrapyard. So, when the script calls for an isolated, austere location with a sense of death and hopelessness, it’s obvious that the location scout will make use of convenient contacts.

The car chases are fantastically staged. Surely some of the best I’ve seen, not for their spectacular OTT stunts but for believable situations shot with directorial brilliance. I was so enthralled that at one point a cut-away to a close-up of throttle action under the bonnet almost brought a tear to my eye for its visual inventiveness and adrenaline-pumping intensity.

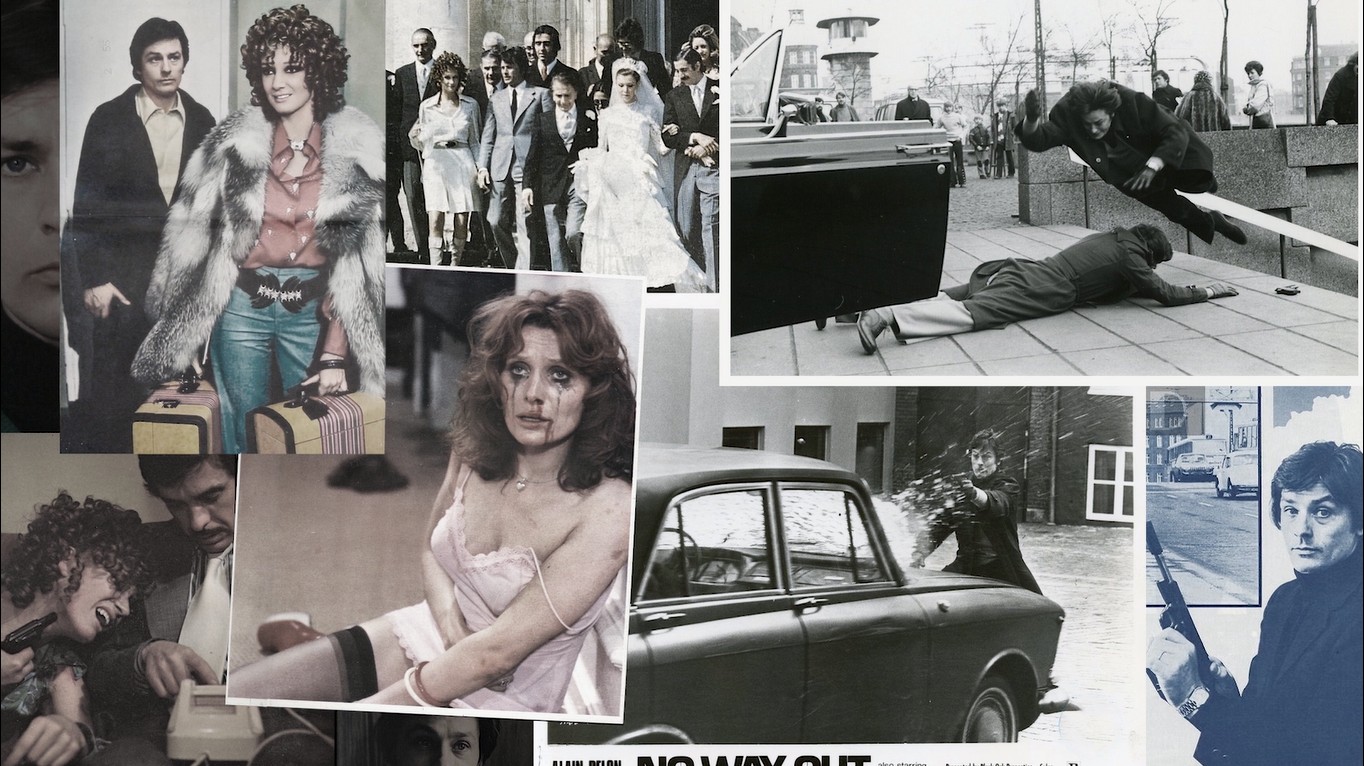

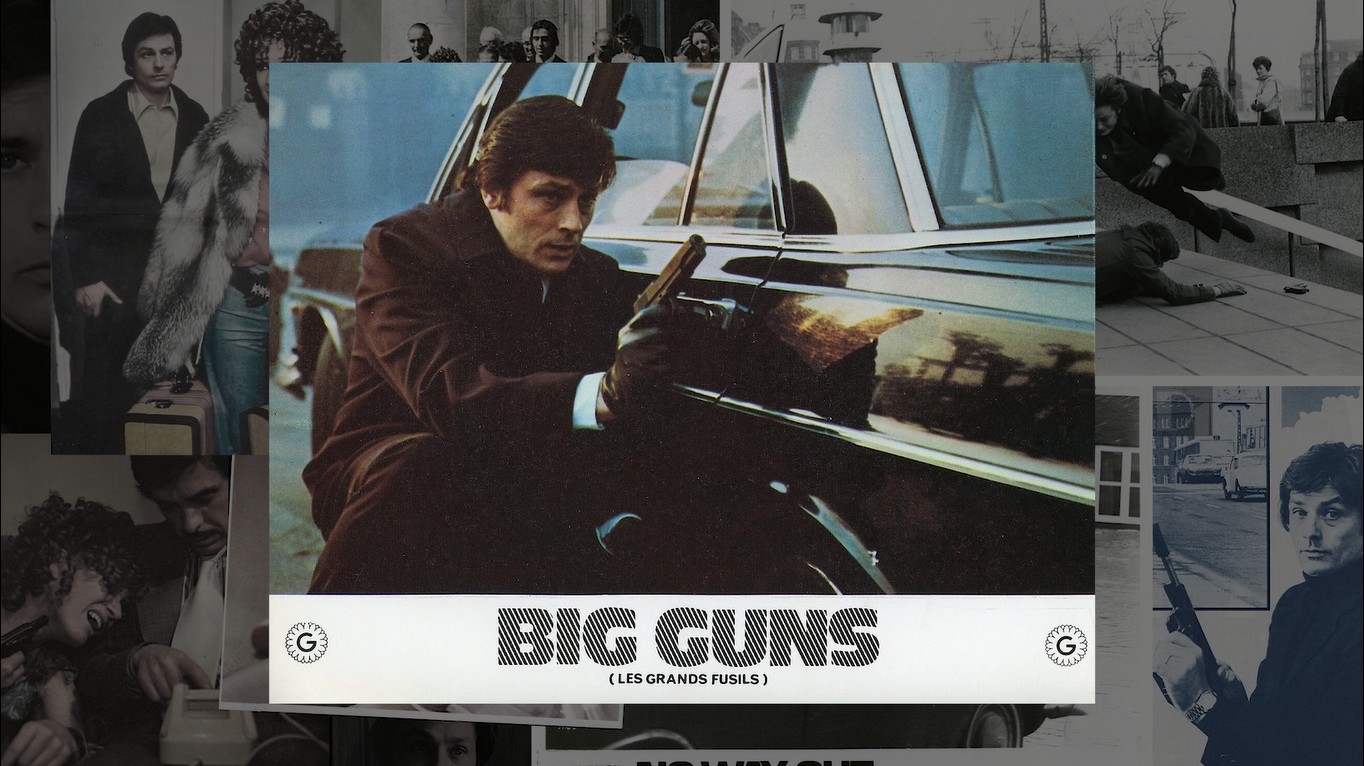

Without Duccio Tessari or Alain Delon, it would be unremarkable. However, while it borrows from then-contemporary directors like Stanley Kubrick, Sam Peckinpah, and Jean-Pierre Melville, this is no mere pastiche. It’s certainly a superior Eurocrime thriller that stands the test of time, remaining as exciting and enjoyable as the period piece it has become. Tony Arzenta was a commercial success, also released under the titles Big Guns and No Way Out.

ITALY • FRANCE | 1973 | 113 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH • ITALIAN

director: Duccio Tessari.

writer: Ugo Liberauce, Franco Verucci & Roberto Gandus (story by Franco Verucci).

starring: Alain Delon, Richard Conte, Carla Gravina, Marc Porel, Roger Hanin, Nicoletta Machiavelli, Lino Troisi, Silvano Tranquilli, Corrado Gaipa, Umberto Orsini & Giancarlo Sbragia.