IN COLD BLOOD (1967)

Two ex-cons murder a family in a robbery attempt, before going on the run from the authorities...

Two ex-cons murder a family in a robbery attempt, before going on the run from the authorities...

The events described in Richard Brooks’s 1967 movie In Cold Blood and Truman Capote’s bestselling book of the same name are, today, more than 60 years old. But in the late-1960s they were the recent past, so the apparently pointless murder of an entire Kansas farm household would’ve brought back memorably shocking headlines, and the two rootless killers—Perry Smith and Richard “Dick” Hickock—remained uncomfortable reminders of the fragility of respectable, prosperous America. (Indeed, those reminders were growing in number by the late-’60s, and the Manson family killings would come in only a couple of years.)

Interestingly, it’s that rootlessness which we see from the beginning: shots of a bus to Kansas City, a car being loaded, a train, a road to a farmhouse, town signs, road signs, all accompanied by Quincy Jones’s restless and insistent jazz score. There’s a sense something terrible is about to erupt, certainly, but also—thanks to all these references to transportation and geography—a sense the terrible something might’ve been floating around the country looking for somewhere to descend and wreak violence, and has only just found it in this farm.

Which was, more or less, the case with Perry and Dick. They were headed to the Clutter family’s property that night in 1959 after receiving information from a prison contact that the man of the family had thousands locked away in a safe. This turned out to be untrue, and they took away less than $50 after than slaughtering the family of four (this utter pointlessness only adding to the story’s horror). But really, if it hadn’t been the Clutters in Holcombe, Kansas, it would surely have been some other family somewhere else; one of the points made by In Cold Blood, perhaps simplistic in modern psychiatric terms but persuasive nonetheless, is that neither Perry nor Dick would have been a killer on their own but “together they made a third personality”—a murderous one, driven by Dick’s ruthlessness and Perry’s impressionability and unrealistic fantasies.

Perry dreams, for example, of being a Vegas singer, and of discovering a fortune in Spanish gold (surely as nonexistent as the Clutters’ safe); Dick, meanwhile, promises that “we’ll blast hair all over them walls”. And there’s a peculiar, not-quite-spoken, not-quite-hidden sexual dynamic to their relationship, too. Dick makes no secret of his voracious taste for women and particularly very, very young ones, yet he frequently calls Perry “sugar”, “honey”, “baby”, and he refers to the pair of them as a “family”. “I’ll show you who’s wearing the pants,” Dick says to Perry at one point, and it’s never clear whether he’s teasing his less sexually forthright friend or alluding to something he can’t bring himself to express openly.

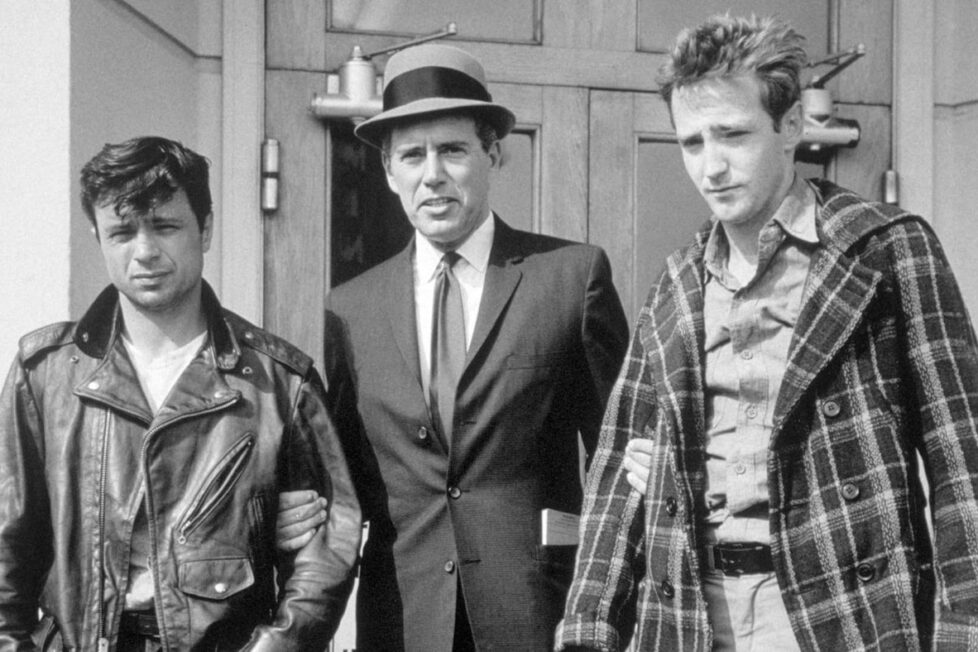

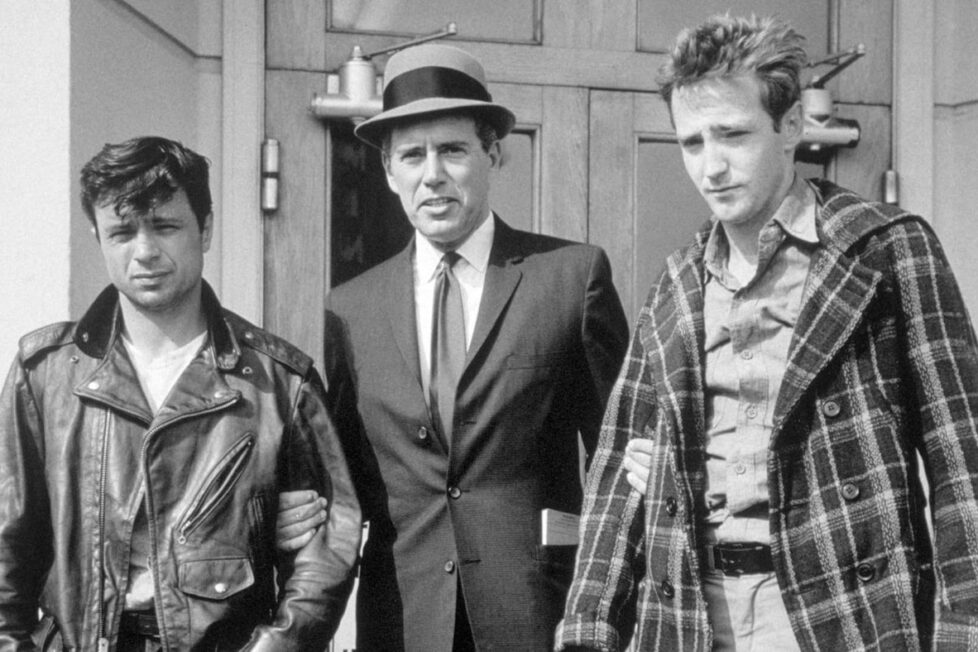

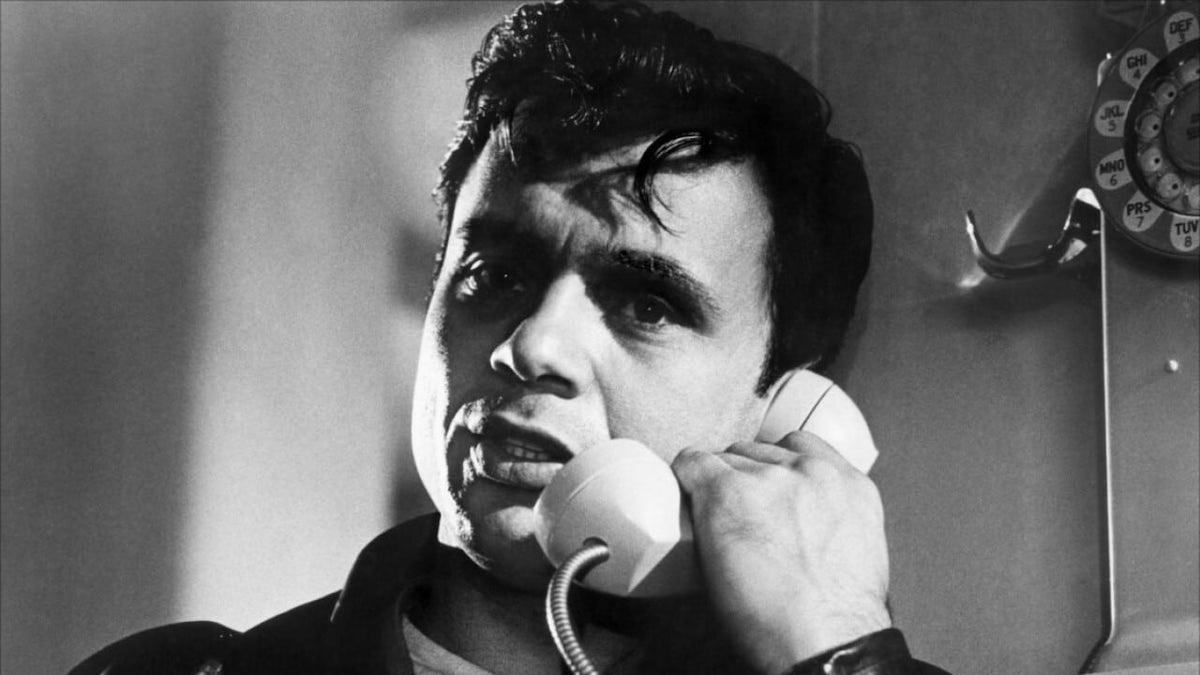

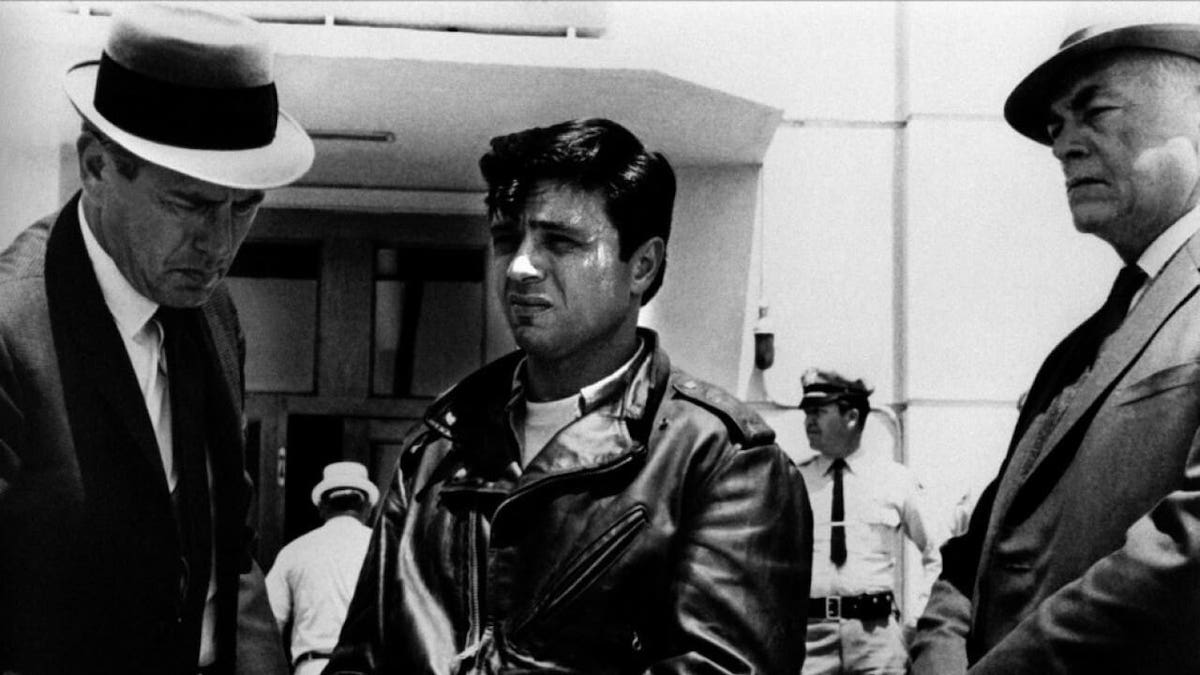

Brooks intentionally cast two unknowns in these parts (observing that “if Paul Newman and Steve McQueen came into your living room at night, you wouldn’t be frightened”), and both Robert Blake (as Perry) and Scott Wilson (resembling a young Kirk Douglas in the role of Dick) are completely convincing. Many scenes make clear their contrasting natures—their different behaviour toward a señorita in Mexico, for example, or a scene where the two are holed up immediately after the crime, Perry nervous while Dick is complacent—but they’re never overdone to the extent the credibility of their friendship is stretched. Dick is cocky and resentful during his police interrogation, Perry much closer to being shattered during his.

As the film progresses, through the killings and investigation to the trial and eventual execution of the pair, it’s clear that Brooks’s sympathy, like Capote’s, lies more with Perry. If not quite sad, his hanging is certainly distressing, and the scene where he is—for once—clearly and simply happy collecting discarded soft drink bottles with a kid they’ve picked up hitchhiking is both revealing and moving in itself.

Even during the crime itself (not initially depicted—at first we see only the discovery of the Clutters’ bodies by neighbours—but later revealed in a long flashback), Perry’s more sympathetic than his partner to the family, pleased to see a teddy bear in the daughter’s room, and attempting to make small talk with her. “I thought Mr Clutter was a very nice gentleman,” he recalls later. “I thought so right up to the time I cut his throat.”

The film is very much dominated by the pair, of course, and they somehow seem ever-present even during the police procedural scenes before their capture. But some other actors do stand out as well, including John Forsythe as Alvin Dewey, the lead detective on the case, and Charles McGraw is striking as Perry’s fast-talking loner and law-abiding father. Differences in his and Perry’s versions of the past may allude to the inherent difficulties which faced both Capote and Brooks in telling a factual story in fictional form.

Brooks puts these people and their story front and centre. The cinematography by Conrad Hall is intense and stylish with strong film noir influences, but of the kind that add atmosphere and tone to the story rather than intruding on it (the shot where rain on a window gives the appearance of tears on Perry’s face, shortly before his execution, was a fluke rather than a contrived effect). Jones’s varied score—a pastoral feel for the first family scenes before horror arrives, a wistful tone for flashbacks to Perry’s childhood—similarly plays an important role in underpinning the drama without pushing itself too far into the forefront. Both Hall and Jones were nominated for Academy Awards, as was Brooks for writing and direction.

There are some differences to the book: notably, though to an extent Brooks preserves Capote’s structure alternating between the family and their killers, he provides much less on the family. The trial which occupies a large part of Capote’s work is also reduced to a single scene here, and a new character, the reporter Jensen (Paul Stewart), is introduced. One might think he represents Capote but really he’s a stand-in for Brooks (a former journalist) himself, there to underline some of the anti-capital-punishment arguments that the writer/director was anxious to make. “In cold blood” has a double meaning, at least for Brooks.

Still, “Capote appreciated the fact that Brooks was not going to be sentimental”, the director’s biographer Douglass K. Daniel (also featured on this disc) has written. And Brooks was largely faithful in spirit if not always in detail to Capote’s approach. The director—true to his own journalistic and documentarian background—conducted extensive research himself (just as the author had), used many real locations (notably the victims’ home) and even hired some of the real participants in the saga to appear in the film, including jurors and the hangman.

If the movie isn’t as well-known these days as other Brooks works—like The Blackboard Jungle (1955), Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958) and Elmer Gantry (1960)—and that’s probably because Capote’s “non-fiction novel”, one of the seminal works of the New Journalism movement which applied the techniques of fiction to the telling of non-fiction, remains so famous itself.

Perhaps, then, In Cold Blood the movie will always be overshadowed by In Cold Blood the book… but more than a half century after its release, Brooks’s film still stands powerfully on its own as a subtle, multi-layered exploration of violent criminals and their crimes, which makes no attempt to excuse them but does request that we at least try to understand them. Perhaps it’s impossible—as Dick’s father (Jeff Corey) rhetorically asks, “how’d anybody know what’s inside another person?”—but Brooks wants us to try.

There are no new supplements on this disc (they mostly date from 2015), but it’s an excellent assemblage nevertheless, with the discussions of music, photography and editing particularly providing some fascinating case studies in how a film is put together.

USA | 1967 | 134 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Richard Brooks.

writer: Richard Brooks (based on the book by Truman Capote).

starring: Robert Blake, Scott Wilson, John Forsythe & Paul Stewart.