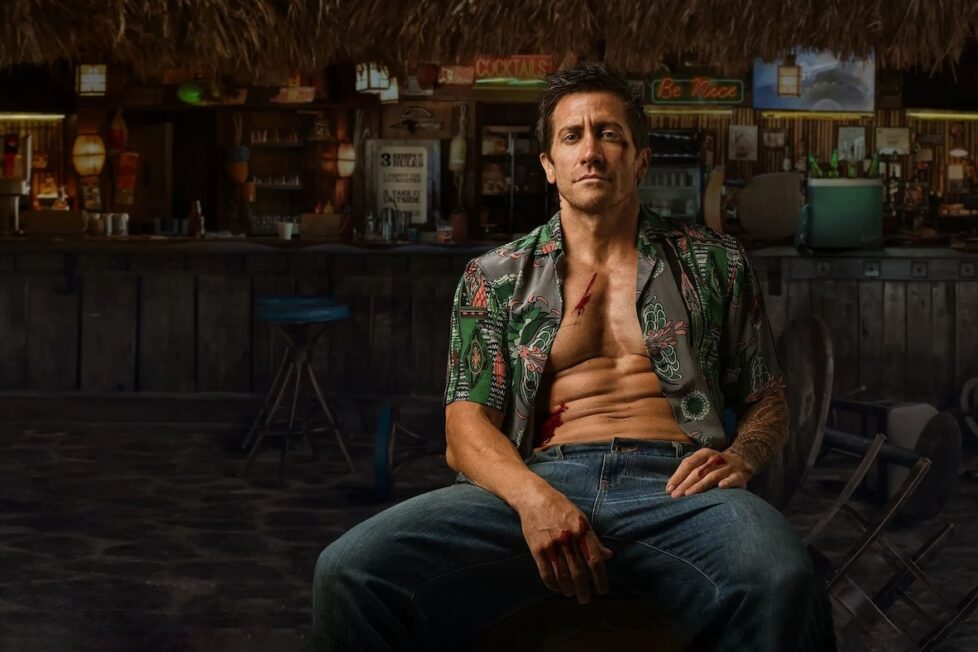

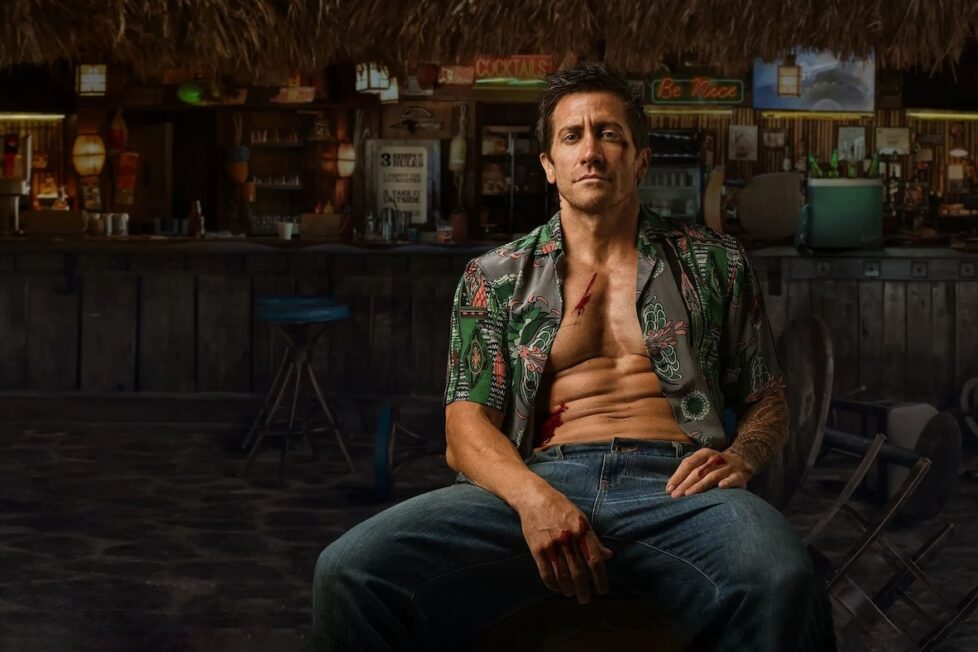

ROAD HOUSE (2024)

Ex-UFC fighter Dalton takes a job as a bouncer at a Florida Keys roadhouse, only to discover that this paradise is not all it seems.

Ex-UFC fighter Dalton takes a job as a bouncer at a Florida Keys roadhouse, only to discover that this paradise is not all it seems.

Crystal-clear blue skies arch above the picturesque titular bar on the Florida coast. Palm trees, boathouses, and secret spots out in the ocean beckon, promising relaxation with a deckchair and a view. However, this little paradise isn’t all it seems…

When Elwood Dalton (Jake Gyllenhaal) is asked to relocate to Florida to help a bar owner (Jessica Williams) protect her establishment from the growing number of thugs in the area, he initially refuses. He has a dark past that’s forced him to give up on life, with his violent history causing him to renounce his skills and seek a completely hermetic existence. However, when he accepts the job offer, he soon realises that if he’s to protect those he cares about, he must rely on his capacity for violence once more.

Road House is nothing more than simple, action-packed fun, but thankfully it never tries to be anything it’s not. You’re invited very early on to switch off your brain and enjoy the show, no matter how nonsensical it might get. However, there are a couple of omissions in the story—mostly concerning character development—that prevent this remake from becoming a complete success. But much like the 1989 original, the characters and plot are there solely to facilitate some cheesy action sequences, which the film delivers in abundance.

In this review, I won’t compare Rowdy Herrington’s Road House with Doug Liman’s remake. There’s plenty of time for that later in the year when Patrick Swayze’s portrayal of the rough-and-tumble bouncer celebrates its 35th anniversary. Instead, I’ll focus on Liman’s film as its own entity.

Liman has claimed this might be his best film. Now, it certainly isn’t that (not by a long shot), but it’s not his worst either. This is the same man who directed The Bourne Identity (2002), a film that seamlessly integrates the protagonist’s character development into the plot’s progression. Here, a man’s confrontation with his dark past—and the capacity for violence that lies within him—serves to show him just how evil he once was and how desperately he needs to change as a result.

This is a trope popularised by the Western genre—particularly films like Shane (1953)—where a character realises that the barely dormant aggression within them is only a destructive force, with no real place in a harmonious society. Road House cleverly draws on this classic formula but adds nothing new in terms of writing or story. Instead, it uses this theme to bolster an otherwise superficial narrative.

Road House is never coy about this connection; characters in the film explicitly try to draw parallels between its story and the Westerns that inspired it, although it never reaches the same pulse-pounding climaxes, nor the profound dramatic depths. While it features a character attempting to escape his violent history, it never delves into analysing the very ideas that made such brooding Westerns so iconic. The plot is almost identical to John Ford’s The Quiet Man (1952), but rather tellingly, it lacks the pivotal moment where Sean Thornton (John Wayne) opens up about his past; Elwood does his talking with his fists and leaves all the sentimental stuff for another movie.

It’s apparent that Liman never truly intended to delve into character psychology; it seems he was content merely to make a crowd-pleasing action film, with a standard, paper-thin mystery plot to create some sense of intrigue between fisticuffs. Even then, the intrigue is kept to a minimum amount of time between physical altercations. In other words, it’s heavy on action and light on suspense, and you’ll probably be happier for it.

However, this complete lack of character development prevents it from ever becoming more than frivolous entertainment. Those I watched the film with said they thought any specific details about Dalton’s past would have been superfluous. This confirms what we all expected going into the film: it was never meant to be anything more than mindless action.

I disagree, however. Mainly because his history is frequently referenced, both in flashbacks and by other characters. But also because the story could have been genuinely poignant if even a little space had been given to his character development. It seems strange that Liman keeps referring to his past concerning his growth as a character, but then refuses to elaborate on any specific details, or what Elwood himself thinks of it.

As mentioned earlier, however, this isn’t the kind of film it aspires to be. Unfortunately for Liman, the film was denied the chance even to become a crowd-pleaser. Amazon opted to release it exclusively on their streaming service, effectively shutting the door on a theatrical run. Needless to say, Liman was disappointed, and so was I. Watching it with friends was enjoyable, but there’s no doubt the atmosphere would have been electric in a packed cinema.

Having said that, there’s also a curious aesthetic to the film that seems to fall squarely into the category of “streaming service content.” Films like Netflix’s Escape Room (2019) demonstrate a similar style, where everything looks unwaveringly fake, plastic, or computer-generated. Perhaps it’s because everything looks like a set, the lighting is very obviously from a lamp to ensure optimal exposure, or the whole image appears to have been run through an Instagram filter; it’s difficult to pinpoint the exact source. But the result is a texture that is starkly contrasted with a studio-produced picture.

I wasn’t sure what to expect going into this film, but I know I was excited to see some on-screen clashes between Gyllenhaal and real-life UFC legend McGregor, who fittingly plays the main antagonist. Unfortunately, most of the fight sequences were marred by exceptionally poor VFX—the quality of which I’ve rarely seen before, resulting in distracting and disorientating camerawork. Under the guise of being innovative, Liman crafts fight scenes that look like they’ve been lifted straight out of a video game. Perhaps video games don’t make people violent, but do they make them think that violence looks like it does in those games?

Fortunately, the performances prevent the film from becoming lacklustre. Gyllenhaal embodies the laconic, roaming warrior character popularised in the aforementioned Westerns of John Wayne, Clint Eastwood, and Alan Ladd. However, he adds an ever-so-slightly goofy element to his persona. He’s both kind and lethal, slow to anger, and uncommonly calm for an action hero. He seems disinterested and composed as he hands out benevolent beatings to loud, brash street thugs.

Occasionally, it feels as though his emotional detachment hinders the plot from kicking into second gear. He seems so uninterested in getting involved that he spends much of the film simply drinking at the bar, even recruiting bouncers to do his work for him. Up until a pivotal moment late in the film, his lack of aggression almost suggests there’s not even a modicum of threat, which ensures the stakes always feel low. Then again, we don’t need another shouty action hero—we’ve seen plenty of those already.

Speaking of loud and obnoxious characters, McGregor makes his acting debut in Road House, and this is particularly evident in his stilted delivery of some of his longer lines. In one or two sequences, there are genuine moments where he appears to have some semblance of screen presence. However, his performance often descends into inane, incessant grinning and overly theatrical wide-eyed mania.

It’s interesting how someone who built a career on their seemingly endless charisma can’t quite translate it onto the big screen. McGregor once thrived on delivering off-the-cuff banter, but struggles to convey someone else’s one-liners convincingly. He often looks as though he’s making an advert—perhaps he should have stuck to making Burger King commercials—and it’s probably for the best that he’s mostly playing himself.

The conclusion of the story feels somewhat arbitrary and only truly makes sense in the context of a common Western narrative arc: a laconic hero rides in, cleans up the town, and then rides off into the sunset. However, Elwood’s decision to leave isn’t established at all. Instead, he simply skulks away, disappearing onto a bus in a rather anticlimactic denouement. The credits roll, but you’re left perplexed; it doesn’t feel like the story should end here, suggesting there are at least two or three more scenes missing from the film.

In the end, you probably won’t mind that much, which is likely because you weren’t particularly invested in his character in the first place. After all, neither was the writers or director. You got what you came for—lovely views, exaggerated fights, and some funny one-liners—and anything more than that would have been extraneous. As a result, the film will never be truly memorable, but it’ll be something you can watch if you’re bored, making it the ideal film for a streaming service.

USA | 2024 | 121 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Doug Liman.

writer: Anthony Bagarozzi & Charles Mondry (story by Anthony Bagarozzi, Charles Mondry & David Lee Henry; based on ‘Road House’ by David Lee Henry & Hilary Henkin).

starring: Jake Gyllenhaal, Daniela Melchior, Billy Magnussen, Jessica Williams, Joaquim de Almeida & Conor McGregor.