TO SLEEP SO AS TO DREAM (1986)

An ageing silent film actress hires a private eye and his wacky but helpful assistant to track down her missing daughter.

An ageing silent film actress hires a private eye and his wacky but helpful assistant to track down her missing daughter.

To Sleep So As To Dream / Yumemiru Yôni Nemuritai / 夢みるように眠りたい is an unconventional, black-and-white, mainly silent, low-budget, indie art film from mid-1980s Japan. But don’t let any of that deter you! It’s also beautiful, poetic, poignant, witty, and surprising. Completely ignored outside Japan upon its initial release, it never found international distribution, so this 2K Blu-ray restoration from Arrow Video marks its belated and welcome first international release. Director Kaizô Hayashi ‘s calling card debut is a difficult film to categorise or fit neatly into any genre. Best described as a fantasy noir mystery, it’s a fascinating treatise on cinema itself—or, more accurately, a cinematic expression of love for the cinema. There are plenty of little details that’ll be lost on those without good knowledge of Japan’s film industry since its inception, but there’s still more than enough to entertain cineastes the world over.

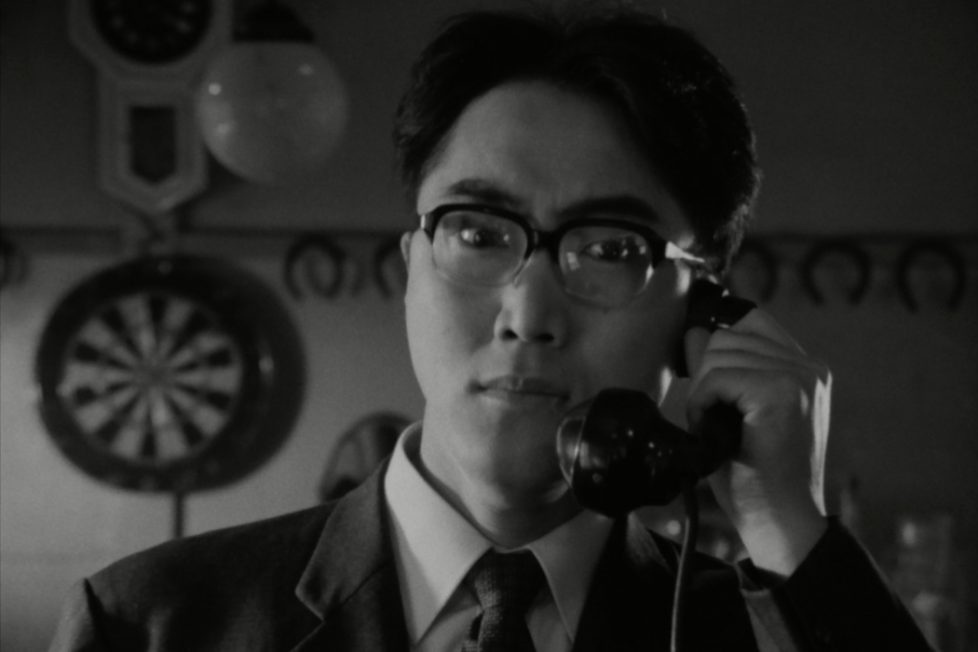

Packaged as a detective story, we meet Outsuka (Shirô Sano) and his sidekick Kobayashi (Koji Otake) between cases. It seems it’s been a long ‘in between’ and they’ve been reduced to sustaining themselves almost exclusively on eggs which are, of course, hard-boiled—as in hard-boiled detectives—and there are plenty of pastiche noir stylings throughout. Eggs become a recurring motif that encourage increasingly profound interpretations. The ‘which came first’ adage is a clever clue to understanding the film as a kind of time machine exploring similar paradoxical riddles.

In one scene, as Outsuka intently ponders an egg, I was reminded of Perspicacity, the 1936 painting by the Surrealist, René Magritte, in which he paints an artist who looks at an egg and, in turn, is painting a bird. He sees beyond the surface of what is and imagines what will be. As the artist in the painting sees the potentiality of an egg, so the artists who painted the picture imagines what was beyond the surface of the canvas, as do we. With the screen for its canvas, To Sleep So As To Dream plays similar games with the surfaces where reality and imagination merge and could be considered an accomplished work of Surrealism.

Also, a film is very much like an egg—bear with me here. Even if one knows for sure it’s a hen’s egg, there are many different breeds of chicken. Likewise, a film cannister gives little away about what film it may contain. If the egg is food, one must peel away the shell to enjoy what’s hidden beneath the surface. But what of the cinema screen? A surface that separates us from a dreamworld of light and shadow where we can still see the ghosts of long-gone events and, perhaps, imagine there to be more substance than there is. To get the most out of this film, there are layers to be peeled away before one may enjoy the delicious mystery within.

An old man arrives at the Uotsuka Detective Agency representing an appropriately enigmatic client named ‘Madame Cherryblossom’ (Fujiko Fukamizu) who offers many times the usual fee to find a missing girl named ‘Bellflower’ (Moe Kamura). The old man (Yoshio Yoshida) proceeds to play a taped recording of the kidnapper’s demands which include a riddle that will lead the detectives to a series of cryptic clues. We read the clues as intertitles as the only sounds we hear for most of the film are foley effects, such a ringing telephones, that will jarringly break the silence.

The casting here is part of the film’s genius. Fujiko Fukamizu was one of Japan’s most famous actresses of the 1930s and this marks her return to the screen after an absence of 45 years since retiring in 1941 when her career was disrupted by World War II. Yoshio Yoshida was a veteran actor of Japan’s post-war period, with well over a hundred movies since the 1950s. For me he was immediately recognisable from 100 Monsters (1968) and will be known by many for his appearances in popular franchises such as Gamera, Zatoichi, and Godzilla. The presence of these two actors would’ve had different connotations for different generations of Japanese cinemagoers and, apart from one small and uncredited role for Fukamizu, this was the final film for both.

It was the debut for both male leads and Shirô Sano would go on to have a prolific career, racking-up hundreds of big and small screen appearances—ranging from chanbara costume dramas, cult sci-fi and horror, soaps, and crime series. Conversely, this remains Koji Otake’s sole screen credit. Both turn in excellent performances, using faces and body language with effective economy in the absence of dialog. Sana keeps his movements minimal and precise and has described his approach as presenting his body as an object like an action figure, posed to interact with the lighting as an extension of the set. Otake is more animated and introduces physical comedy including an almost slapstick kung-fu fight sequence, we also get to see him in vignettes of his character’s imagination as we pierce another layer of presented reality.

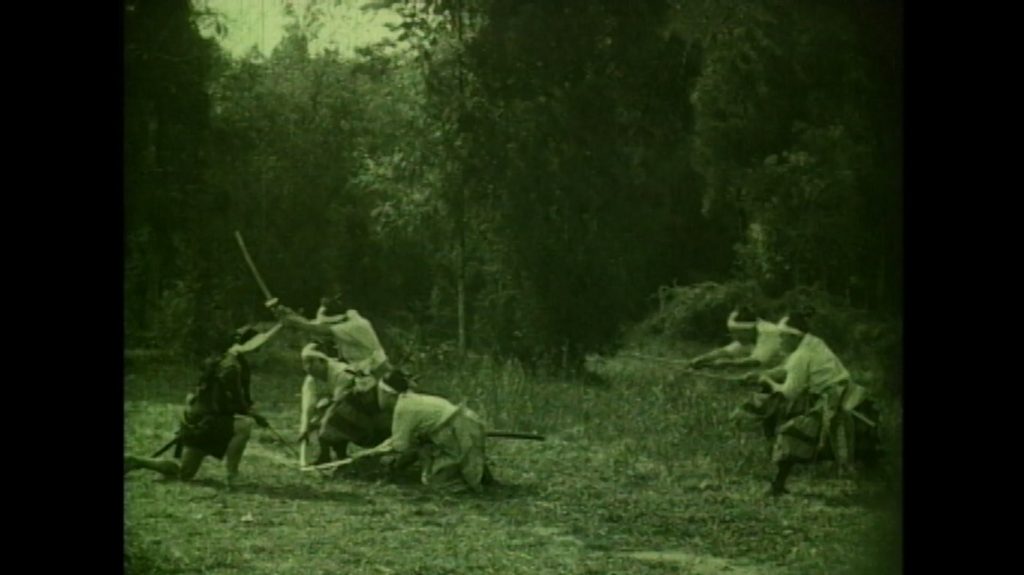

The film oscillates between a somewhat anachronistic setting that appears to be the 1940s heyday of film noir and several nested narratives that use film as a non-linear dreamworld. We’re treated to a backstory comprised ostensibly of film clips from the silent era and when the final clues lead our protagonists to the site of the first ever cinema in Japan, The Electric House, a poetic tale unfolds that bridges from 1903 into the viewer’s present.

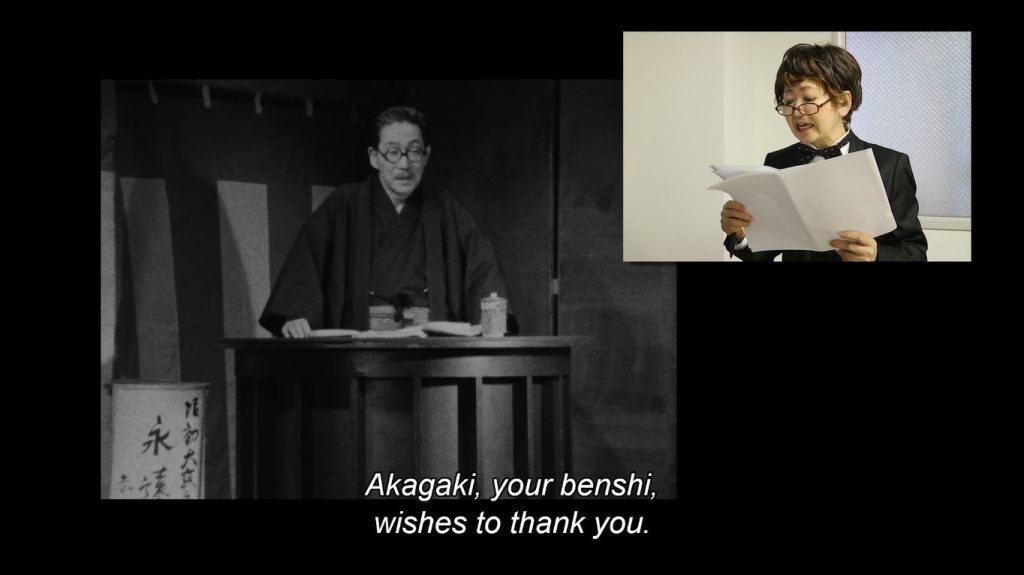

Along the way, three street magicians crop up from time to time, complicating things and delivering further clues. These cameos are provided by Kazunari Ozasa in his only film, and two notable celebrities in veteran character actor Akira Ôizumi, and folk rock musician Morio Agata—who also had a hand in the score. He co-wrote the hauntingly beautiful theme song “Eternal Mystery” with Moe Kamura, who performs it in the film. Hers is one of only two voices we hear throughout, the other being the benshi at the Electric House Cinema. Benshi were the narrators for the first silent movies in Japan, continuing a tradition of storytelling that already existed where street performers would tell tales, often with a supernatural element. They illustrated their performances with by picture cards to be revealed in sequence or scrolls that they would crank along—early forerunners of films, which, if one thinks about it, are really very long picture scrolls. So it was natural for them to interpret and perform the stories for, first silent movies, and then the first foreign talkies to be imported…

As this Blu-ray turns out to be the international debut release for To Sleep So As To Dream, albeit delayed by three-and-a-half decades, I don’t want to spoil any surprises here. Suffice to say the plot deals with an unsolved puzzle from the silent era when Japan’s first actress had to pretend to be a man in the role of a woman. Yes, you read that right, actresses were banned as ‘morally corrupting’ and had to be played by men who specialised in feminine portrayals. Hence, we have a rich subtext that tackles gender politics, censorship, and the significant part cinema played in purveying revolutionary ideas that challenged the oppressive, expansionist ideology of Japan’s Imperialist Showa era. The authorities could cut and censor the films themselves, but a live benshi was a different matter and harder to keep tabs on.

One wonders how director Kaizô Hayashi managed to make such an assured and accomplished debut as writer-director-producer. He had no formal film-related training and dropped out of an economics degree, which may’ve been what put him in good shape to work such magic with a meagre budget, equivalent to about $60,000. He was clearly a fervent cineaste and knew to surround himself with some veteran talent on both sides of the lens.

Cinematographer Yûichi Nagata had already been in the business for about a decade and had shot more than 25 movies, albeit mainly straight to video and ‘pink’ sexploitation fare. He makes the most of monochrome to cover any shortcomings in lighting with dramatic contrast and deep shadows. Which was the same motivation behind the development of the Noir style in the first place—to compensate for the cheapness, or lack, of set.

Here though, production design is in the hands of Takeo Kimura, one of Japan’s most respected art directors. He’s known for his collaborations with cult director Seijun Suzuki, best showcased in the stylistically audacious pop art aesthetics of Tokyo Drifter (1966). For To Sleep So As To Dream, he crammed the sets with lots of interesting and often incongruous details that add interest to every corner of the frame. He also knew how to make the most of large spaces with minimal stage dressing that when photographed by Nagata evoke Hollywood noir or, in some scenes, the structural boldness of earlier German Expressionism.

To Sleep So As To Dream is, predictably, very dreamlike with an intrinsic logic that immerses the viewer into its strange and unique world. In some respects, all films become ghost stories, repeating imprints of the past. Sometimes, the people and places we see survive only as patterns of light and shadow, no longer existing in the solid world. Films are time capsules. So, what if one could step into a film, either the year it was made or the period of its setting. Here, we find ourselves drawn deeper through screens within screens, films within films, until we reach an achingly poignant conclusion in an audacious finale that’s as fragile, transient, and gorgeous as a dream of falling blossom.

JAPAN | 1986 | 71 MINUTES | 1.37:1 | BLACK & WHITE | JAPANESE

writer & director: Kaizô Hayashi.

starring: Morio Agata, Kenji Endo, Fujiko Fukamizu & Bakken Jukkanji.