Mohsen Makhmalbaf: The Poetic Trilogy • GABBEH (1996) • THE SILENCE (1998) • THE GARDENER (2012)

A collection of Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf's movies, comprising his 'Poetic Trilogy'...

A collection of Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf's movies, comprising his 'Poetic Trilogy'...

Mohsen Makhmalbaf is a revolutionary filmmaker in every sense. (After watching these three films, and the accompanying interviews with the director, you’ll realise just how clever I’m being with that opening remark!) Iranian by birth but, becoming a persona non grata in his homeland, he made more than 30 films in 11 different countries, and is now recognised as Iran’s most important filmmaker. Except in Iran, where all his work is now banned, and it’s forbidden to mention his name or even refer to his work in the media…

Despite being selected for the 1996 Cannes Film Festival and winning a handful of international accolades, Gabbeh was banned in Iran for being too subversive. A western audience will struggle to grasp this subversiveness and will instead find themselves enjoying a dreamlike, visually rich story of love and longing.

The story starts with a dotty old couple coming down to a river to wash one of their prize possessions, a type of Persian rug known as a ‘gabbeh’. The old man (Hossein Moharami) is the complaining sort, and speaks in a weird sing-song way that you’ll either find endearing or really irritating—but there is, eventually, a reason for it. His wife (Rogheih Moharami) is more stolid but certainly has a sense of humour, though it soon becomes clear her grip on reality has faded over the years.

The pattern woven into their rug illustrates a story, and as the rug is immersed in the water a mysterious and beautiful young woman (Shaghayeh Djodat) emerges. She recounts her own tale, which is interwoven with the stories of the rug itself and, as it turns out, the old couple. So, we’re told two linked stories in flashback, both about love and finding the ‘right’ partner.

One story follows a middle-aged man (Abbas Sayah), referred to as ‘Uncle’, who’s been unsuccessful in finding love in ‘the city’ and has returned to his nomadic roots among the Qashqai tribes of Iran. His homecoming is tinged with sadness as, in his absence, his mother died, leaving an unfinished rug on her loom.

He’s dreamt he would find his wife by a spring, singing like a canary—and, lo!—he indeed finds a woman washing pans in a spring, singing a melody of her own composition. He’s so impressed by her poem that he’s inspired to compose one himself, which begins “Looking is not seeing, Behind every cradle there is a grave, Behind every joy, sadness…” and ends with the couplet “my body is like a cold, silent dungeon, But my heart is like a happy child.” She likes his poem so much, she says she’d be glad to accept him as her suitor, and so his sadness is replaced with joy and their love story looks set to be a happy one.

One of the younger girls of the family, whom we recognise as the mystery girl from the gabbeh, doesn’t find love so easily. Although they’ve never met, she’s infatuated with a mysterious horseman, whom she only glimpses at a distance, but who’s been following a trail of scarves she’s been leaving for him. In the night, he lets her know he’s still near, by imitating the cry of a wolf. The young girl’s father forbids her to marry until she finishes weaving the gabbeh her grandmother started. When she eventually achieves this goal, he comes up with more excuses for her not to marry the mystery man… and their love story soon follows a more tragic trajectory, or so it seems.

At the time Makhmalbaf made Gabbeh, he was finding it impossible to have any of his scripts approved by the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, but when he was approached by a company that wanted a film to promote sales of traditional gabbeh, he dressed up his ideas as a documentary and managed to get the go-ahead.

The film doesn’t disappoint as a documentary as we do see the craft of making the rug: the gathering of plants to be boiled for natural dyes, the shearing of the sheep, the spinning of the yarn, the painstaking craft of hand-weaving the rug from start to finish by the women in the community. So, if that kind of anthropological stuff interests you, you’ll be more than happy, and it’s all beautifully photographed, too. A scene where the family cross a river with their livestock is almost a homage to Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life (1925), a much earlier—some say the first ever—ethnographic documentary that records the hardships of nomadic life in Persia.

Gabbeh is a masterclass in slow but assured visual storytelling—it would’ve been fairly clear even without the subtitles. The pacing is measured, the imagery lyrical, the structure more like music with repeating motifs—the rhythm of the loom, the cycle of life. Not really a plot as such, but a poetic narrative… well, the clue’s in the title of this trilogy!

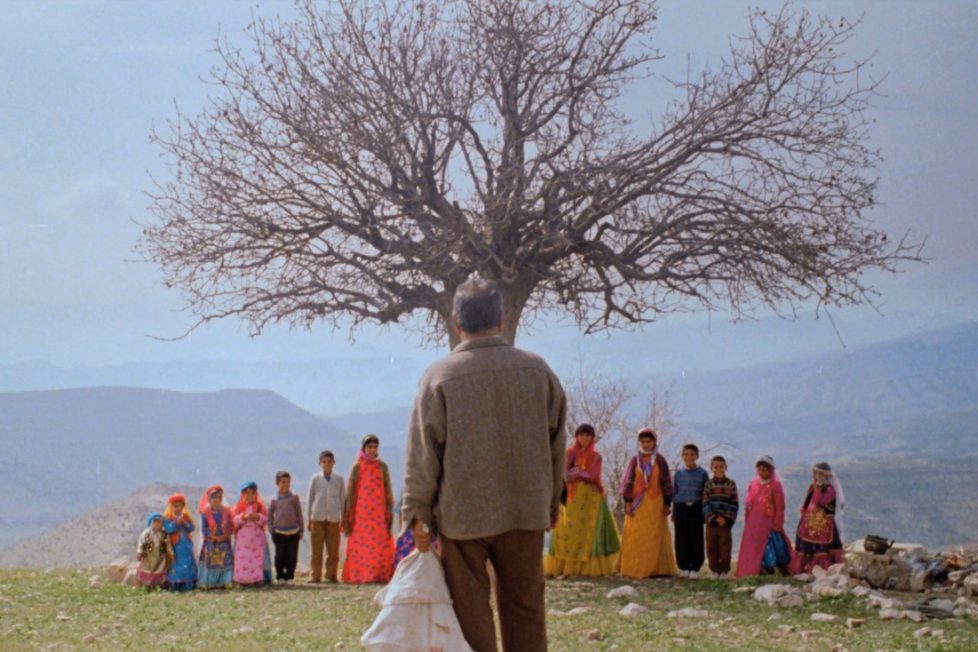

So how could this be subversive? My favourite sequence could well hold some clues. As ‘Uncle’ approaches a yurt he hears children’s voices reciting their times tables by rote. Inside the tent he finds a group of boys and brightly dressed girls being taught together. He then interrupts the class to give a lesson of his own.

His teaching style is much more, er… poetic, as he magically takes colours from the world around them. He points to a meadow of crimson blooms and suddenly there’s a bunch of the red flowers in his hand. Same thing happens when he indicates a field of corn-yellow flowers. Then he points skyward and his hand is blue. He grasps the sun and his other hand is instantly turned a golden-yellow. This is a beautifully simple but effective piece of cinema, using montage and cuts to create the illusion of magic, rather than sophisticated visual effects. Somehow it’s more profound and less easily dismissed. He speaks of how colour is life… then we become aware of this as a key concept throughout the remainder of the film. Colour is also the main thing that links this trilogy.

The women wear their brightly-coloured clothes and stand out against monochromatic colour fields—the screen is often a flattened plane of colours and forms, just like the rugs are. In another scene the tribe move through a landscape of subdued hues across which many gabbeh are laid out to dry. The yarn is from the land, via the sheep. The colours are from the land, via the plants and flowers. The stories are from the land, via the people who live upon it and are told in the figurative motifs woven into their traditional rugs. Their lives become the folktales of their descendants.

So, not only the education of girls, but in unsegregated classes? That’s just one thing that may be subversive. The colourful dresses worn by the womenfolk, when the government advised only grey and brown should be worn—could be provocative. The idea of the land and a people’s relationship with it being so important, almost as if god can be expressed through nature—that might be a point of contention to a religion that maintains that god is transcendent and unknowable. The use of figurative, rather than geometric patterns, well, that’s frowned upon. The celebration of the gabbeh as part of an ancient Persian folk culture just might remind Iranians that Islam is relatively young and owes something to the past.

The film is also very influenced by Sufi philosophy in general and by the poems of Rumi in particular. In one scene, the empty loom frames a desolate field of long golden grass as it dances in a whispering breeze. The sense of absence and the turning of the seasons is almost palpable and evokes the famous opening lines of Rumi’s epic spiritual poem, the Masnavi, “listen to the reed and the tale it tells, how it sings of separation…”

Which brings us nicely to the second film in this Poetic Trilogy…

Early in production of The Silence, Makhmalbaf had a brief flirtation with Hollywood and was offered a substantial budget. Of course, he considered this, but eventually turned it own in favour of a much smaller offer from a French producer. He wanted to keep his films intimate, working on a human-scale with small cast and crew—which seems to include several members of his own family. He also understood the bigger the budget, the less control he’d have.

This is a much simpler film with an uncluttered narrative. I missed the interwoven stories and more complex imagery that Gabbeh had led me to expect, however. The Silence felt more like a ‘student film’, reminding me a little of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Steamroller and the Violin (1961), which shares themes of childhood and music, and is poetically linked through the use of metaphor and overall structure—and both films end with a dream-like sequence.

The Silence tells the story of Khorshid (Tahmineh Normatova), a blind boy from an impoverished home in Tajikistan who earns the rent money for his single mother (Goibibi Ziadolahyeva) by tuning instruments. It seems that every morning he captures a ‘bee’ in a glass and, before releasing it, listens to the buzzing as some kind of portend. Of course, he’s unable to see each insect and finds it impossible to distinguish between a bee and a wasp.

Before going to work, his mother takes him to buy bread from a line of young girls. Khorshid is immune to the charms of their pretty faces and colourful dresses, so isn’t distracted from his selection of the best bread. He fingers and feels each piece of bread as he passes (not sure about the hygiene here) before making his final selection. So, it’s surprising when he later tells his mother that the bread is too dry and admits he was fooled by a pretty voice.

It seems he can find beauty in the sounds he hears all around him: the birdsong, the trot of a horse, the lapping of water. He even hears the heavy, insistent knocking of the greedy landlord as the first few bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony! This becomes the central motif.

Of course, the irony of watching a film—predominantly a visual medium—about a blind boy who doesn’t see what we see is completely intentional. The visuals of The Silence are similarly flattened and painterly, as they were in Gabbeh. Figures become forms moving across planes of colour, a blank wall, the water of a lake and gradually, the use of sound becomes more prominent. This counter-play of what we see and what Khorshid hears makes the audience think about the ways we experience, perhaps even judge, the world around us.

Khorshid travels by bus to the musical instrument workshop where he works and is instructed to plug his ears with raw cotton, so he doesn’t wander off in pursuit of an attractive sound. Though, sometimes, he’s unable to resist the temptation to pull out the plug and have a sneaky listen. Apparently, this is an autobiographical detail. Makhmalbaf was raised by his grandmother, who was very strict and thought of music (and films) as sinful. So, if the young Mohsen was in the street and there was music to be heard—from an open door or workman’s radio—-he had to put his fingers in his ears to avoid eternal damnation.

Daily, Khorshid is met from the bus by Nadareh (Nadereh Abdelahyeva), an orphan girl who guides him to the workshop where she lives and works. She serves tea to the craftsmen as they carve rough wood into elegant instruments, but she takes every opportunity to spend time with him. Here the film changes into the delicately understated story of their innocent friendship. When she goes to the river to fill her kettle, she pauses to pluck petals from flowers and stick them to her fingernails, or to hang berries from her ears. This adornment is of course wasted on Khorshid, whom she helps to tune the new instruments by dancing—her way of knowing if they sound right.

These two young actresses (yes, Khorshid is played by a girl) deliver finely balanced performances, making both these kids very likable, and you really want to know how things turn out for them… so the open-ended finale might be a little frustrating for some.

Again, there seems very little to get upset about in what is basically a story about finding friendship in an unforgiving world, and using your senses to appreciate the beauty around us and engage with life to the full. Initially, it was accepted for a limited distribution in Iran on its strengths as a documentary about the craft of making traditional instruments, though the scene of Nadareh dancing—which is very subdued—was cut because public dancing is illegal. Then the Iranian authorities grew steadily more uncomfortable with Makhmalbaf’s portrayal of child labour and poverty, which could be taken as critical of the government, not to mention a young girl who chooses not to cover her hair… so, eventually, an outright ban was imposed.

Makhmalbaf explains that with this poetic trilogy, he uses the formal element of colour as a unifying motif and takes his structural cues from Sufi music and poetry. As he sees it, the cinema traditions of the west stem from a heritage of visual culture—painting and sculpture—whereas in the east, they have historically revered music and poetry. Indeed, the Sufis attribute mystic, transcendent qualities to them. This is probably best demonstrated in the Dervish Sama ceremonies, where they whirl themselves into a trance-like state of ecstasy to the music in the hope of unveiling cosmic mysteries and attaining a spiritual connection with god. This shift in emphasis is something that The Silence hints at with its focus on sound and rhythms that lead to a kind of spiritual transcendence for Khorshid.

Which brings us nicely to the third film in this Poetic Trilogy…

Although the first two films have aspects of documentary, The Gardener is the only straight-up documentary of the three, and all-the-weaker for it. At times, the formal composition is still strikingly beautiful and continues flattening the picture plane along with the prominent use of sound. But this is a collaboration between Mohsen and his son Maysam and their approaches never quite gel—which I think is the point.

On the surface, it’s an investigation of the relatively young Bahá’í Faith, which sprang from Iran 170 years ago and has attracted 7 million followers around the world. It interested Mohsen mainly because there have been no incidents of Bahá’ís resorting to violence, even though they’re often on the receiving end of aggressive persecution. They see themselves as a unifying force that will eventually provided a bridge between all faiths and nations. But the documentary is really about a relationship between a father and son.

Throughout, we’re eavesdropping on their debate about whether religions of any sort are valid. Maysam seems to think religion is responsible for most of the world’s ills, war, bigotry, and so on, believing that technology is more likely to unify the world. Mohsen, who introduces himself here as “an agnostic filmmaker”, points out that religions may spark war, but wars are waged with technology. They talk, Father to Son, and for a while I was worried it might all end up a bit Cat Stevens. It does become very self-referential, with shots of them chatting whilst setting up the camera and sound equipment, ignoring the third camera and crew that is inevitably filming them.

“What do freedom, peace and kindness have to do with religion?” asks the young Maysam. “These all depend on culture. The basis of war has its roots in religion.” Mohsen concedes, “the power of religion is undeniable. It can take innocent children and teach them to kill and to die—why not use that power to promote peace and friendship?” Well, that’s a very good question.

Early on in the film, there’s a luscious shot of an ancient olive grove, carpeted with sunshine-yellow meadow flowers. Immediately a scene from Gabbeh is recalled, when Uncle explains that colour is life and we are one with nature. We are keyed into that poetic symbolism again. Then it’s all spoilt by a young woman trotting through the shot, pretending to be a bird or something, flapping her shawl like she’s taking part in some sort of lame amateur dramatic exercise. Then again, maybe I’m being a little harsh—she seems happy enough and the cameraman, Maysam in this case, must run to keep up with her.

He then proceeds to interview several of the Bahá’ís about their beliefs and how they came to be at the main temple of the faith in Haifa, Israel, which they call the Universal House of Justice. They all seem pleasant and well-meaning but have that beatific vacuity that seems endemic to the devout of most organised religions. There’s even a prolonged shot of a group walking towards camera, their faces blank, eyes staring zombie-like at something we can’t see.

They espouse tolerance and an appreciation of nature, coming across as an extension of the hippy movement—until you delve a bit deeper with further research. And there lies the main flaw in the documentary: it lets them speak, but they don’t really give much away and I became increasingly suspicious of how their organisation was funded, who administered it and what the Bahá’í tenets really are… which you can Google easily enough.

Whilst Maysam is filming short interviews with a few of the followers and visiting other religious sites, such as the Wailing Wall, Mohsen’s been napping in the shade between bouts of filming the head gardener tending the plants. He recognises their respect for nature as central to the Bahá’í belief and this (poetically) aligns with the underlying message of both Gabbeh and The Silence: if we use all our senses to engage with the natural world, its colours, tastes, sounds and textures, then we can be in harmony as part of creation.

Ultimately, I don’t think The Gardener draws any profound conclusions. It’s fairly interesting if you haven’t heard of the Bahá’í Faith, and it’s a nice honest snapshot of a father-son relationship. There are a few more symbolic, perhaps surreal sequences that add interest and resonate a little with the first two films and we conclude with Mohsen planting his camera in a flower bed.

For the average viewer, who doesn’t mind subtitled foreign movies, Gabbeh is the most rewarding of the trilogy. It’s as beautiful to look at as a National Geographic travelogue and it holds back a surprise twist right to the final scene. The Silence has its moments of beauty, too, but the simpler narrative and metaphorical conclusion will only really appeal to the arthouse crowd. And I’m not at all sure about The Gardener—again, there are some truly gorgeous compositions, and I understand that it’s being anti-Hollywood and deliberately unconventional, but I found it a bit of a chore to get through.

writer & director: Mohsen Makhmalbaf.

starring: ‘Gabbeh’ – Shaghayeh Djodat, Hossein Moharami & Rogheih Moharami • ‘The Silence’ – Tahmineh Normatova, Nadereh Abdelahyeva & Goibibi Ziadolahyeva • ‘The Gardener’ – Ririva Eona Mabi, Paula Asadi, Bal Kumari Gurung & Ian David Huang.