THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE (1974)

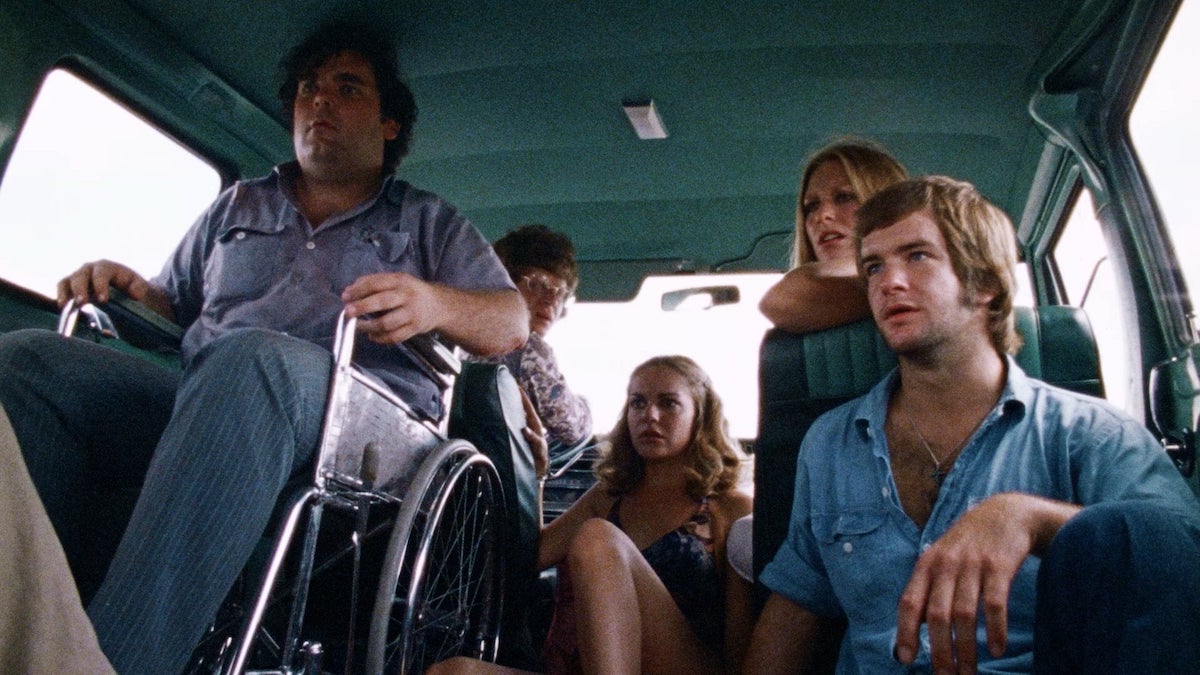

Five friends head out to rural Texas to visit the grave of a grandfather, but stumble upon a family of cannibals.

Five friends head out to rural Texas to visit the grave of a grandfather, but stumble upon a family of cannibals.

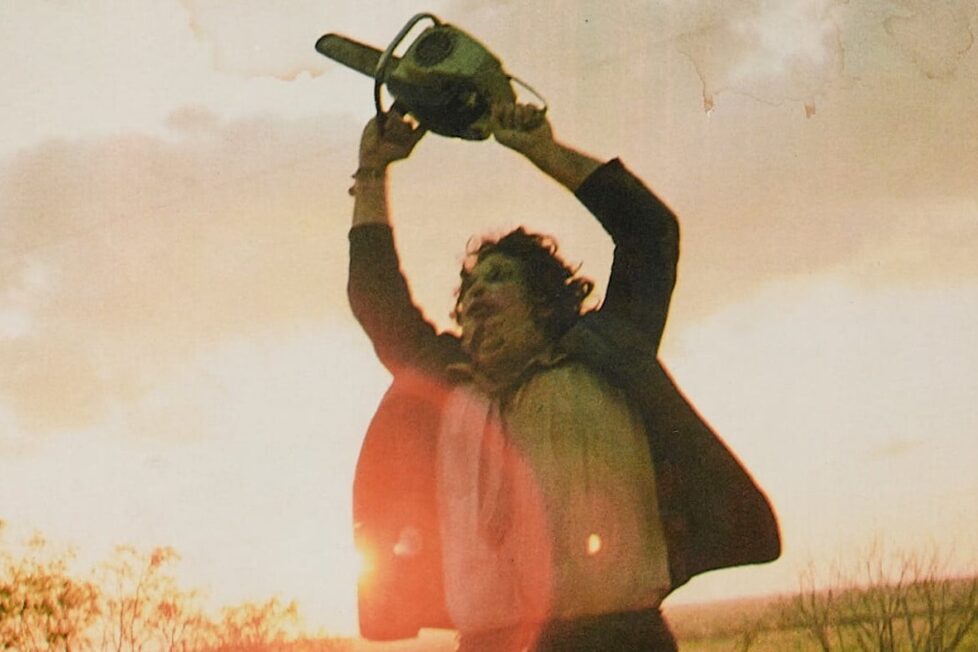

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is a cosmic horror. Taking one step away from the comforts of society, and Sally (Marilyn Burns) and her friends find only terror and madness. A universe where humanity is a mere plaything for unknowable horrors. We never learn the family’s name, let alone their firsts, and the once-uttered ‘Leatherface” (Gunnar Hansen) could be a throwaway insult. Nor are they dead, they merely wait, and soon they shall wake; “a whole family of Draculas” feeding blood to their decrepit patriarch whose more Nosferatu than Bela Lugosi. There are monsters in the real world.

Titles fade over a blood-red sun as “the news programs detail an unusual number of natural disasters” as the screenplay phrases it. A mental hospital collapses for no reason, four children found with their “features carved away”, a month-old baby chained in the attic of a young couple. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is but “one of the most bizarre crimes in the annals of American history.” Between bleak substantiated facts and bleaker astrology horoscopes, a man tries to take a roadside piss as his wheelchair careens down a hill. The cosmic indifference rolls on.

Horror, comedy, a wrong turn off the edge of civilisation, all marketed on true events. The intentional misinformation of writer-director (also producer and co-composer) Tobe Hooper was a fiery response after being “lied to by the government about things that were going on all over the world.” Watergate, the oil crisis, and “atrocities in the Vietnam War” were all laid bare with a “lack of sentimentality and the brutality of things.” Alongside co-writer Kim Henkel, Hooper was inspired by the graphic coverage of local news “showing brains spilled all over the road” to venture ever so offroad and tell a contemporary folktale that “man was the real monster here, just wearing a different face.” That would become quite literal and this allegory would place much emphasis on the gory.

Aliens, vampires, giant ants, communists; all foreign menaces repelled by the top brass, scientific minds, and American family values. Yet the ever-evolving horror genre was blossoming challenging proto-slashers with subversive attitudes. Psycho (1960), Night of the Living Dead (1968), and The Last House on the Left (1972) all turned the vice on our concepts of a functioning civilisation and showed how good ol’ all-American folk can destroy each other after a very bad day. The mask, the weapon, the setting, all are signatures of the slasher. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre remains an unforgettable experience after generations of ‘relatives’ vying to succeed the grandaddy of modern horror.

Through Daniel Pearl’s superb cinematography, Hooper delivers such raw imagery in documentarian fashion—from animal carcasses to long rotted remains—that it threatens to overwhelms one’s senses with an unwavering cloud of death. Pam (Teri McMinn) retches at the skeletal décor from the catalogue of Ed Gein in a stunned silence that lasts longer than the actual deaths of Jerry (Allen Danziger) and Kirk (William Vail). What’s so viscerally upsetting is the absence of any hope of escape; they’re dispatched with such abrupt efficiency that the hammer crushes their skulls before breath has time to escape your lungs as a scream. Dead. If you’re lucky! Pam is left swinging on a meat-hook, and then left freezing in a refrigerator, and then she’ll remain in that house as a lampshade or maybe a shoe rack.

There’s an auteur argument to who’s more significant: the director who comes up with all the sights or the guy who puts them there? When that entails taxidermizing an armadillo, Robert Burns deserves the highest of praises for his art direction. Along with all the furniture filling the house, Burns decorated Leatherface. Look closely at those three iconic masks and you’ll spot holes and stiches in the cranial vicinity; Burns accounted for the fact that’s how Leatherface kills his ‘cattle’.

“I shot the scene all the way up to just before the sledgehammer and I already had this little ramp built on the floor. So I rehearsed the scene and there was something missing. I didn’t have a button on it to make the next shot to make it as powerful. ‘I need a door. We have to stop. Bob Burns, can you deliver a door to me in an hour?’ So when I had the door there, I just said, “Throw him in, dude, and just slam that damn thing.” It would be hard to do that today on a film.”

Tobe Hooper

Perhaps he wanted one less task, but Burns is credited as the one who convinced the director the SFX of a meat hook through Pam was best left to the imagination. Hooper genuinely believed limiting the onscreen blood might secure the film a PG rating (this was before PG-13 existed), even calling the Motion Picture Association of American (MPAA) which was met with “a long silence” before a relented yes.

Other than avoiding an NC-17 rating, there was another reason why Leatherface was so quick in killing. He was the all-American victim against a foreign menace. Practically every single other slasher is predatory in nature, but Leatherface is merely defending his territory. Jerry dies in the exact same manner of Kirk and the moment his body collapses off-screen we spend a disquieting pause with this inhuman goliath having a full-blown panic attack because he’s home alone and these strangers just keep wandering into his home. TCSM confounds the emotional responses in the audience by having us ask why is the monster so scared of what’s happening.

The answer is obvious now that The Texas Chain Saw Massacre has become intellectual property, but for the audiences of 1974, they had no idea how an early joke was actually a setup. Hooper withholds this reveal until the third act, but Leatherface is a product of being raised by a “whole family of Draculas.”

The chaotic Hitchhiker (Edwin Neal) belies his spontaneity as he teases his marks, attempting to convince them to come for dinner as his “whole family’s always been in meat.” His shocking and bloody theatrics only drive them toward the Old Man (Jim Siedow) who seems to sincerely warn them away from these parts. He still sells them his homemade barbecue under the ‘We Slaughter’ sign at his gas station. We never get a mention or sight of cannibalism in the original TCSM, but Sally cuts the meat with the switchblade that still has Hitchhiker’s blood on it… which is disgusting enough. These two vocally joust over control of the household, with “look what your brother did to the door!!” remaining one of the funniest lines in any horror for revealing so much of their relationship with so little. Leatherface non-verbally pleads that he did a good job protecting the house, unable to compliment him, the Old Man stutters “you damn fool, you ruined the door!”

Hooper always lamented that his comedic elements went unappreciated, one hopes this alleviated the real horror on location. Much like The Exorcist (1973) and The Shining (1980) the authenticity was fuelled by the shared experience during production.

The house had little ventilation and no cooling which became a pressure cooker for the walls of animal blood and bones scavenged from the local slaughterhouse. Burns would drive around finding roadkill accoutrement, some of which was burnt outside to dispose of. It didn’t work. “I wouldn’t let them see the location until I started shooting and I shot lots and lots of takes” Hooper explained. “I would separate the actors and not let them socialise.” Vail would have the running chainsaw brought to within three inches of his face. Paul A. Partain would remain in character as Franklin. Equally anxiety inducing events.

Hansen later recalled the price it paid to become Leatherface, “it was 95, 100 degrees every day during filming. They wouldn’t wash my costume. I wore that [mask] 12 to 16 hours a day, seven days a week, for a month.” Temperatures peaked at 110°F (43°C). For his four weeks, Hansen earned $800. “I would have made more money if I’d worked in McDonald’s those numbers of hours,” he later said. The climactic dinner scene reportedly took 27 hours to shoot, though some allay it was only the usual 16 hour day, and that “Hooper probably has it up to 40 by now.” I think of the brief shot as Pam and Kirk cross the threshold of that property and a pocket-watch hangs with a nail driven through and then what happens to them. You’re here forever.

Not enough could be said of Marilyn Burns, as no other Scream Queen has conveyed such raw unrelenting terror. Tied to a chair and then forced to her knees with her face in a metal bucket, her only resort is to unleash everything in her performance in a desperate attempt to sway her tormenters. Given how all her friends and family have been eliminated so abruptly, we and Sally are tortured with the suspense of what their intentions are. The Hitchhiker relishes in getting one over these city-folk, the Old Man reasons “it can’t be helped” while his giggles betray his good conscience, and Leatherface in his Pretty Woman mask can’t stop staring at her, touching her hair, sizing up Sally’s face. What’s left of her lungs after the exhausting chase sequence with Leatherface prior goes out to no-one as the family only join her in primal wolf calls. In her lowest despair she quietly sobs “Please, I’ll do anything you want”, which goes ignored. And she does give everything; the crew couldn’t get the stage blood to pipe through the tube during Grandpa’s feeding so they cut Marilyn Burns with a razor.

This was the last day of shooting and wrapping should’ve been as cathartic as the last-minute freedom for Sally. Then a call the next night: “we didn’t get it, we gotta reshoot this.” As Burns reveals, “when I was crazy at the end of the movie laughing hysterically, that was not acting, that was me having to go back and do this one last time.”

“Everyone hated me by the end of the production, it just took years for them to kind of cool off. I was having my own party by just watching them sitting by myself, and it occurred to me that everyone had got a ding on the head or a cut or this or that [but] I somehow managed not to get messed up. And I leaned back in the chair and a piece of the porch broke and I flew back into a pile of 2×4’s with nails sticking out of it and got nail-punctured all over.”

Tobe Hooper

Banned in several countries, cinemas stopped showings due to complaints. In San Francisco, people walked out in disgust. Two theatres in Ottawa faced morality charges lest they withdrew the film. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was resubmitted to the MPAA after several minutes were cut from its 83-minute runtime to receive an R rating. Yet one distributor restored the cut material and at least one theatre presented the original version under the new rating. For eight years after 1976, theatres would annually reissue the film promoted with full-page ads in the paper. The Texas Chain Saw Massacre could not be stopped, grossing just shy of $40M on an estimated budget of $140,000.

The British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) not only banned the movie, but the word “chainsaw” was barred from all other movie titles. The BBFC eventually passed The Texas Chain Saw Massacre uncut with an 18 certificate, and it was broadcast a year later on TV. This was 26 years later in the year 2000. BBFC’s President, Andreas Whittam Smith, said “for modern young adults accustomed to the macabre shocks of horror films through the 1980s and 1990s, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre is unlikely to be particularly challenging.”

Much like that extra day for Burns, the suffering didn’t end after the wrap party. The cast and crew were encouraged to defer part of their salaries until after the film was sold to a distributor. Production company Vortex Inc. did award them a share of potential profits, ranging from 0.25% up to 6%. Exceeding the original $60,000 budget up to egregious ranges from $93,000 to $300,000, a film production group called Pie in the Sky provided $23,500 for 19% of Vortex. The Texas Film Commission secured distribution with the Bryanston Distributing Company, who took $225,000 and 35% of the profits. The cast and crew, including Hooper, now owned 40.5% of their movie, and this wasn’t disclosed during the salary talks, meaning their points offered were worth less than half the assumed value.

After the investors, commission, lawyers, and accountants were all paid, $8,100 was left to the 20 or so people who made The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. A silver lining was Bryanston getting their asses sued into bankruptcy for failing to pay them their owed box office percentage. In 1983, New Line Cinema picked up the rights and generously gave the producers a larger share of the profits from the original film, as well as starting production on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986).

After hurling herself through a window (another real and dangerous stunt), Sally flees with nothing but pure adrenaline dragging her away from that hellhole. With the Hitchhiker slashing at her back, the Black Maria reduces him to roadkill. His defilement of the graveyard is what brings Sally to check on her grandfather, who used to drive cattle up to the old slaughterhouse, which then closed down and is inferred to put the murderous family out of work, and now a cattle truck saves Sally’s life. The news may suggest the world is falling apart, but there may be a cosmic order at the end of it all.

USA | 1974 | 83 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Tobe Hooper.

writers: Kim Henkel & Tobe Hooper.

starring: Marilyn Burns, Paul A. Partain, Edwin Neal, Jim Siedow & Gunnar Hansen.