TANK GIRL (1995)

A girl is among the few survivors of a dystopian Earth. Riding a war tank, she fights against the tyranny of a mega-corporation that dominates the remaining potable water supply of the planet.

A girl is among the few survivors of a dystopian Earth. Riding a war tank, she fights against the tyranny of a mega-corporation that dominates the remaining potable water supply of the planet.

Watching Tank Girl again, I wish I’d caught Birds of Prey (2020) in cinemas. There are clear comparisons to be drawn between the chaotic heroines of Tank Girl and Harley Quinn. And yes, I’m aware Tank Girl was created four years before Harley and got her own movie before studios gave up on distaff comic-book movies after Catwoman (2004) and Elektra (2005) flopped. Tank Girl is worthwhile viewing decades later for its subtle advancements of feminism. For all its faults, the movie was a wrecking ball to mainstream expectations of what a female-led popcorn movie could be.

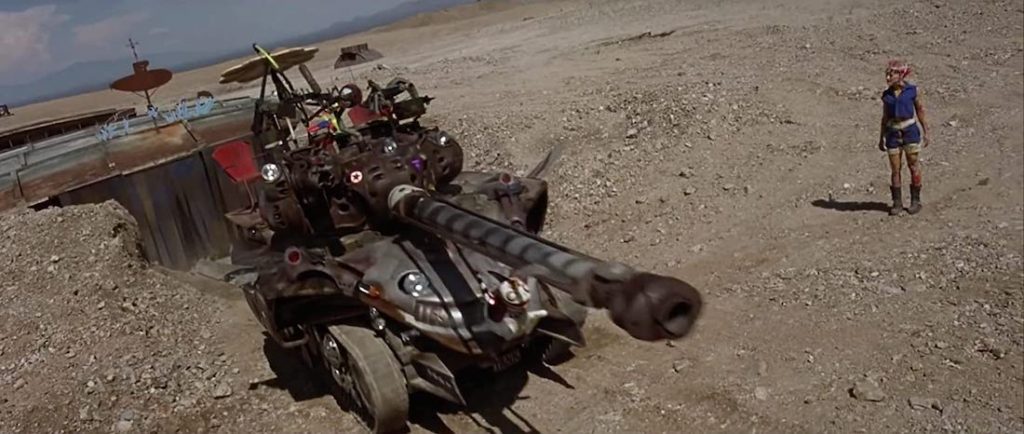

In 2033 A.D, several years after a meteor caused global droughts that transformed the Earth into a Mad Max-style wasteland, free-spirited survivor Rebecca ‘Tank Girl’ Buck (Lori Petty) angers the oppressive Water & Power corporation hoarding the planet’s H20. Refusing to kneel to ‘The Man’, she and her best-friend Jet (Naomi Watts) help genetically-modified kangaroo soldiers in battling the company’s villainous CEO, Kesslee (Malcolm McDowell).

The high-concept pitch is, to modern eyes, Harley Quinn: Fury Road. But while Max was a former cop upholding the last echo of masculine order, Rebecca’s out to prove that fun can survive an apocalypse. This is felt throughout the film as director Rachel Talalay took heed of the advice given to her by John Waters while producing Hairspray (1988) and Cry-Baby (1990): “make the movie that you want to make”. Talalay demonstrated this attitude early with her barmy ‘conclusion’ to the Nightmare on Elm Street franchise, Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare (1991); from teens finding themselves trapped a video-game controlled by Freddy Krueger, to the villain’s own screaming head hurtling towards audiences in stereoscopic 3D.

With that experience arose some love-hate backlash. If you wanted something similar to Wes Craven’s original, you sure didn’t find it with Talalay’s sixth Elm Street. And with Tank Girl, if you expected Mad Max (1979), you weren’t going to get that either. As Talalay said: “I wanted to make a film that was a plus or a minus, you either get it or you don’t.” And while I appreciate a lot about Tank Girl, I’m aware of some glaring issues.

Opening with a frenetic montage of comic-book artwork by Tank Girl co-creator Jamie Hewlett (who later designed the cartoon band Gorillaz), the sequence determined whether or not this film’s for you. Roughly 25% of the movie relies on this cartoony style to cover the $25M budgetary restrictions to help do Tank Girl justice. While pre-Twilight production designer Catherine Hardwicke does an admirable job, the fix-it-with-duct-tape approach to filmmaking grows increasingly noticeable because most action set-pieces are held back for the finale.

Luckily, the performances are just as vibrantly animated to keep the tone cohesive. Lori Petty nails the eponymous bad-ass chick role so effortlessly. McDowell even praised his experience shooting the movie, likening it to A Clockwork Orange (1971), in which he gleefully drinks water drained fresh from his unwilling minions before exclaiming “lovely!” And it’s worth mentioning the presence of a pre-fame Naomi Watts, of course.

As much as I enjoy the pop-punk aesthetic of Tank Girl, it feels as though Tank Girl herself wrote chunks of the script. Film critic Roger Ebert’s main gripe was how non-stop everything felt, but I’d argue the opposite! After Tank Girl introduces herself and the world, she messes up guard duty one night and lets a death squad take out her friends who’ve been siphoning from Water & Power. The first act tests her devil-may-care attitude under imprisonment, forced labour, and torture… which starts the story with the hero at her lowest point, which makes for a jarring arc. It’s like wanting to see Harley Quinn have fun doing crimes, but she’s literally restrained in Arkham Asylum for the first half-hour.

After this initial slog, we move from wacky moment to bonkers moment with little motivation until all the characters have been established and the final battle begins. Witnessing Rebecca parachute alongside her automated tank, spraying down bullets to Ice-T’s “Big Gun” is a genuine joy, however—and not just for the zaniness but the satisfying development of an actual narrative. A sequence to poorly contrast with is when her ten-year-old friend is sold to an upper-class sex club and Rebecca performs a full song-and-dance routine to Cole Porter’s “Let’s Do It”. It’s unashamedly entertaining in visuals and Petty’s performance but narratively frustrating because her silly antics only get her friend kidnapped again.

The other questionable element of Tank Girl is the feminism. I worded that to get a reaction, as Girl Power is definitely a good thing! I like Tank Girl! However, speaking as a (mostly)cis man the ever-so-slight differences between 1990’s feminism and modern feminism creep in. Birds of Prey explored Harley recovering from a long stint of co-dependency which drove her to find real friendship with other women, and their combined emancipation was bolstered by a refreshing rapport with other women. Rebecca, however, comes across as a loner like Clint Eastwood in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966) dragging poor Jet along like Eli Wallach.

Jet’s a woman who grows to accept that pacification may avoid conflict but also harnesses her inner Tank Girl to aid in the revolution, but Rebecca never teaches her directly. A moment many fans love is Rebecca saving her from likely rape by kissing her (which the man’s luckily repulsed by), but she still saves the day by forcibly smooching a shy stranger. Soon after, Jet saves her life in return but Rebecca promptly throttles her demanding she help her escape.

No doubt seeing Watts and Petty kiss was a pivotal moment for young queers in the mid-’90s, but there’s also the impression when meeting the half-kangaroo Rippers that Tank Girl encourages Jet to engage with overtly horny men. It’s a dated concept that casual hetero sex is just what Jet needs to come out of her shell. But just because Tank Girl’s cool with hooking up doesn’t mean that Jet’s fine with it too! It reminded me of when Ally Sheedy got a makeover in The Breakfast Club (1985) and her character’s identity was suddenly altered; the solution to becoming a stronger woman is becoming exactly like Tank Girl?

I almost feel guilty that my retrospective has been ‘tainted’ by a sour note. For anyone who hasn’t seen Tank Girl yet, watch the trailer to get a taste of its Adderall-pumped punk aesthetic. It’s a surprisingly gorgeous experience that isn’t hampered by my criticisms when one’s being distracted by Malcolm McDowell with a holographic head deflecting tank-fired beer cans with his cyber-arm to a soundtrack compiled by Courtney Love.

Becoming a cult classic since its disastrous box-office gross of $6M in 1995, Rachel Talalay genuinely believed her outrageous female action hero was going to change things. And she did, eventually. Margot Robbie herself is currently trying to produce a reboot (she’d make a great Tank Girl, but the character’s perhaps too close to Harley Quinn), and pop-culture for comic-book movies has flourished into a scene for loud and proud women. With only two features on her filmography, which were both seen as disappointments, Talalay instead carved out a success in TV directing popular shows like Doctor Who, Sherlock, and Riverdale. And even with all those fandoms, fans at conventions still bring her Tank Girl items to sign.

director: Rachel Talalay.

writers: Tedi Sarafian (based on the comic-book by Alan Martin & Jamie Hewlett).

starring: Lori Petty, Ice-T, Naomi Watts & Malcolm McDowell.