HAGAZUSSA: A HEATHEN’S CURSE (2017)

Paranoia and superstition in 15th-century Europe.

Paranoia and superstition in 15th-century Europe.

Hagazussa: A Heathen’s Curse presents a problem. It’s not an easy film to categorise and almost impossible to enjoy. It’s not really a horror film, despite being marketed as such. It’s more a ‘horrible film’; one that’ll make you feel terrible rather than terrified. It deals with a serious subject matter and contains imagery that seems calculated to trigger people with depression and mental illness. So, there’s no way I can recommend it. To anyone. But does that make it a bad film?

It’s nightmarish, for sure, and perhaps the grimmest thing I’ve watched since Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist (2009). So its appeal is limited to genre completists who want to be able to talk about it with authority. Or, perhaps, the kind of viewer that sees sitting through intensely unpleasant movies as some badge of achievement. I managed to find my own way into the film by appreciating its many overt references to the visual arts and other films I love…

It bears all the hallmarks of a film made by a young and enthusiastic director still searching for their own style and the confidence to express it. Which is exactly what it is. Lukas Feigelfeld started production on Hagazussa whilst still an undergrad student at Berlin’s Film and Television Academy. It was there that he first collaborated with a fellow student, Mariel Baqueiro, with whom he later founded the production company Retina Fabrik.

Baqueiro’s cinematography for Hagazussa is one of the film’s strong points and its lovely uses of landscape offer some respite to the otherwise claustrophobic candle-lit interiors. There are several dimly lit sequences, some of which have been darkened further in post-production so that only liminal features emerge and drift out from disconcerting shadows. It sure is a dark film in every respect!

It must be a pleasant surprise for Feigelfeld, as well as rather daunting, that his crowd-funded low-budget first feature has made such a big splash on the international festival scene. Perhaps reviewers are doing him a disservice by comparing it to the films that clearly informed it.

Understandably, it’s drawn comparisons with another debut film, Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2015). Both films do share a similar colour-drained milieu, but The Witch has explicit supernatural overtones that Hagazussa barely hints at. The main thing that sets them apart is that the former is a folktale, whereas the latter merely draws upon folklore iconography, avoiding any semblance of becoming a tale…

Feigelfeld falls back on the extensive use of surreal imagery, non-linear dream logic, and a story told from the point of view of an unreliable narrator who descends into increasing insanity. So, who knows? The narrative thrives on ambiguity in nearly every aspect and demands the viewer to put in much of the work. The film it most reminded me of was Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) or, if I’m being charitable, David Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977)—another debut from a young and enthusiastic director.

It’s noteworthy that Feigelfeld also studied both philosophy and art history prior to film school. Clearly, it’s not just cinema that’s influenced the look of Hagazussa. It draws upon gnostic philosophy and also from the infamous Malleus Maleficarum. Compiled by the mad Catholic priest Henricus Institoris, that book was responsible for triggering the cruellest stage of the Spanish Inquisition on its publication in 1487. It categorised sorcery as a form of heresy punishable by death, describing the various ways to identify witches, how to extract confessions and the best methods of execution to be used.

Feigelfeld has explained, in interviews and in a commentary accompanying some scenes, that he basically treated Malleus Maleficarum as a sort of ingredients list. He interprets the signs of sorcery described in the text as being of natural origin such as the symptoms of disease, and manifestations of madness. He also sees that much of the Inquisition was about the persecution and oppression of women in a concerted attempt to deny them ownership of their sexuality. The film is laced with sexual tensions, violations and guilt.

In essence, Hagazussa is a tragic biography of an outsider growing up in very troubled times. The film’s structured in four linked chapters. The first segment, ‘Shadows’, opens with a stark white snowscape dotted with dark-clothed figures in a series of beautiful, almost illustrative compositions.

We’re introduced to Albrun (Celina Peter) as a child and her mother (Claudia Martini), and through simple exchanges of looks we see that they care for each other, but in snatches of overheard dialogue of those who pass them, we sense implied threat.

Seeing young Albrun wandering across wild, unforgiving landscapes with her shawl wrapped around her head reminded me very much of Toss (Fiona Kay) from Vincent Ward’s sublime and superior Vigil (1984). The same intelligent yet innocent eyes trying to make sense of what’s happening in the sparse adult world around her. They’re both isolated and surrounded by superstition. The films share many themes, including a young girl coming-of-age whilst coming to terms with great loss and loneliness.

At night, fur-clad and behorned pagan ‘Wild Men’ terrorise mother and daughter in their cabin. It seems their intention is to take Albrun, now she has reached puberty, or at least ‘borrow her’ for a while. The motivations of the men and the vulnerability of the women are obvious.

It doesn’t take long for things to turn even darker as the mother succumbs to the plague and we see that Albrun is a brave and caring young girl being forced to grow up much too quickly. The disease also brings delirium and the loving mother figure morphs into a scary mad hag.

‘Shadows’ is the most traditional chapter in terms of narrative and contains genuine tension and moments of horror. The deliberate pushing of archetypal motifs linked to the maiden and the hag is effectively unsettling. Both Peter and Martini are excellent, with the younger actress turning in a naturalistic, heart-rending yet understated debut performance.

After the darkness of the first part, ‘Horn’, opens with bright and beautiful landscapes. Years have passed and we join Albrun (Aleksandra Cwen) as an adult leading a seemingly idyllic life tending her goats among the mountains. She still lives in the same house and now seems to be a mother herself, though any father is conspicuous by his absence. The implied threat is still there and Albrun suffers bullying from the local kids who throw stones at her as she takes her milk to market.

When another young woman, Swinda (Tanja Petrovsky), befriends her and leaves her a nice rosy red apple, we get the feeling things are going to turn really bad again. After all, it doesn’t take an extensive knowledge of folklore to understand the symbolism of the apple… remember Disney’s Snow White? (Now, there was a truly terrifying witch!)

Swinda throws in disparaging remarks about heathens and Jews and highlights the theme running through the film: persecution and dehumanisation of those deemed to be ‘The Other’. The second section is when the film turns truly nasty after the relatively light themes of plague and child abuse we endured in the first…

This section has a Werner Herzog vibe, especially when Albrun makes her way up to the typically Tirolean church to visit the priest in his impressive ossuary. He makes vague allusions to the darkness in her heart and kindly gives her a decorated skull. She takes this skull home and sets up a little mossy altar for it in the corner.

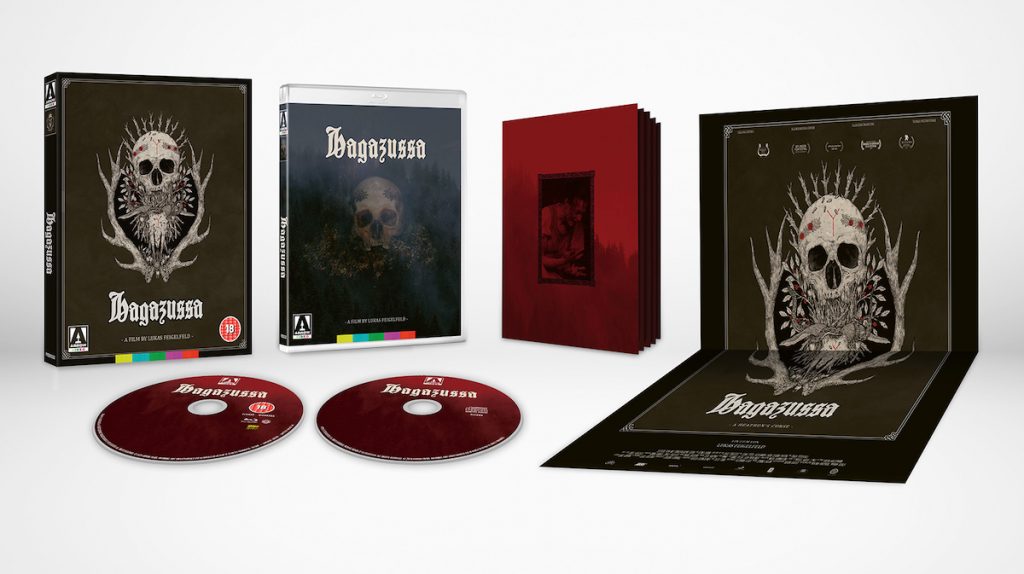

This skull is the film’s most iconic single image, widely used in its promotional material, and directly references the gnostic paintings of Italian artist Agostino Arrivabene, particularly his 2015 Veritas sequence. It also put me in mind of the imagery associated with German Metalcore maestros Caliban. Then I remembered the short film by Mauritz Maibaum that accompanied their 2016 single “Paralyzed”, which touches upon spookily similar themes and imagery.

Come to think of it, the visual narrative of Hagazussa would’ve been a lot easier to accept in the format of a music video: a medium we’re used to seeing challenging imagery and don’t necessarily expect a linear narrative. The soundtrack, by Greek band MMMD, plays a huge part in evoking the brooding atmosphere and holding the film together. Their monolithic sound is very reminiscent of the drawn-out and expansive soundscapes of Sunn O))).

Hagazussa’s slow metre also references the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, whom Feigelfeld also cites as a touchstone. The lingering shots of faces running through enigmatic expressions are a homage to the great Russian director and when Albrun is pushed too far and ritually washes her hair in a kind of self-baptism, the scene is a dark reflection of the similar scene in Mirror (1975).

At the close of ‘Horn’, such bad things have happened to Albrun (and her goats) that I was hoping for a turn-around from victim to victor in the style of Wes Craven’s Last House on the Left (1972) or Meir Zarchi’s I Spit on Your Grave (1978)…. but Feigelfeld intends to deny us such satisfaction.

With the third chapter, ‘Blood’, we return to the imagery of Agostino Arrivabene. In a dreamy, hallucinogenic sequence, that is either murder-suicide or ritual sacrifice and rebirth, we see the body merge with nature, blood with water, flesh with the land. Then things just go from disturbingly weird to downright disgusting.

There is an aspect of beauty to nearly every shot, so much so that it makes some of the stomach-churning imagery almost seductive. There’s little else, though, to relieve the unrelenting morbidity. Not a lot of laughs or light-relief to be had when your subjects include vomit, disease, death, decomposition, child abuse, persecution, animal cruelty, bestiality, racial bigotry, loneliness, misogyny, rape, depression, creeping insanity, substance abuse, hallucination, psychopathy, infanticide, cannibalism, suicide…. Did I already mention vomit?

Wow, that list makes it sound way better than it is! It’s a wonder there’s so much crammed into such a slow-paced film, but don’t get too excited, half of those themes are merely touched upon and the rest remain veiled with ambiguity.

It seems that Goya’s Black Paintings were a rich source of the witchy mythos and visual style. In the latter years of his life, the Spanish artist Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (better known simply as Goya) moved to a modest house near Madrid. He painted all the interior walls black and set about creating 14 murals, including some frighteningly grotesque and powerful imagery. It’s thought he would show them to selected guests using only dim lamplight, as a kind of grand guignol performance.

The pictures would emerge from the dim void, appearing like figures in a nightmare, barely visible, flickering and inconstant. The most famous panels are known as Saturn Devouring his Son and The Sabbat. Goya was no stranger to the subject of witchcraft and he repeatedly returned to the theme.

In another treatment of the Sabbat, haggish witches offer up both dead and living babies to the great goat, and another of his paintings shows a group of witches terrorising a man, one carries a basket of babies like some ghoulish picnic hamper. These paintings also inspired much of the imagery in Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan (1922), a definite precursor that’s also divided into four acts.

In the style of Schrödinger’s Cat, Albrun’s baby seems to be ambiguously living and dead for much of the film (or perhaps even imagined) and when Cwen mimics Saturn’s pop-eyed mad stare from the Goya painting, well we can guess what’s coming next…

Which brings us to the closing chapter, ‘Fire’, and its baffling finale. Feigelfeld maintains that he avoided supernatural elements and that his film remains in the realms of the real. As that may be, it’s not a realist film. The final shots are contradictory as they do seem to support a supernatural reading. It makes no sense in terms of historical and contextual setting. It’s either poorly researched, or perhaps it is supposed to be timeless?

Albrun’s mother dies of bubonic plague. The symptoms detailed by the convincing make-up are accurate. This would imply a setting around the time of the Black Death, mid-14th to 15th-century, which also ties-in with the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum.

However, hagazussa is an Old German word for witch, found mainly in Ecclesiastical documents and some runic texts, from the area now known as Austria and not used much after the 10th-century. This may be more of a clue to the non-specific medieval setting of the story being even earlier. If so, then the painted skull that has become emblematic of the movie is anachronistic. As far as I know, such skull painting is peculiar to the Bavarian town of Hallstatt, which makes sense as far as location goes, but represents a tradition not practised before 1720. So that means the story is set in the 18th-century.

Whatever! It’s best we simply accept that it’s neither horror film nor historical drama and there’s not much that we can be sure of… except that it’ll split opinion and stimulate debate among its audience. Some of the more extreme, envelope-pushing imagery will certainly remain in the memory long after the final credits.

I’m just not sure if that’s really much an achievement. I mean, it’s really not that difficult to push buttons and boundaries if that’s all one intends to do. But I really don’t think that was the goal and suspect that Feigelfeld intended to make his mark and showcase his directorial chops. To demonstrate how he can handle a cast—very adeptly. How he can use audio-visual alchemy to evoke emotions—he does that, too. I will certainly look out for his next film which, hopefully, will be less derivative than this flawed, attention-grabbing debut, whilst keeping some of the immersive intensity he’s clearly capable of.

AUSTRIA/GERMANY | 2017 | 102 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | GERMAN

writer & director: Lukas Feigelfeld.

starring: Aleksandra Cwen, Celina Peter, Claudia Martini, Tanja Petrovsky & Haymon Maria Buttinger.