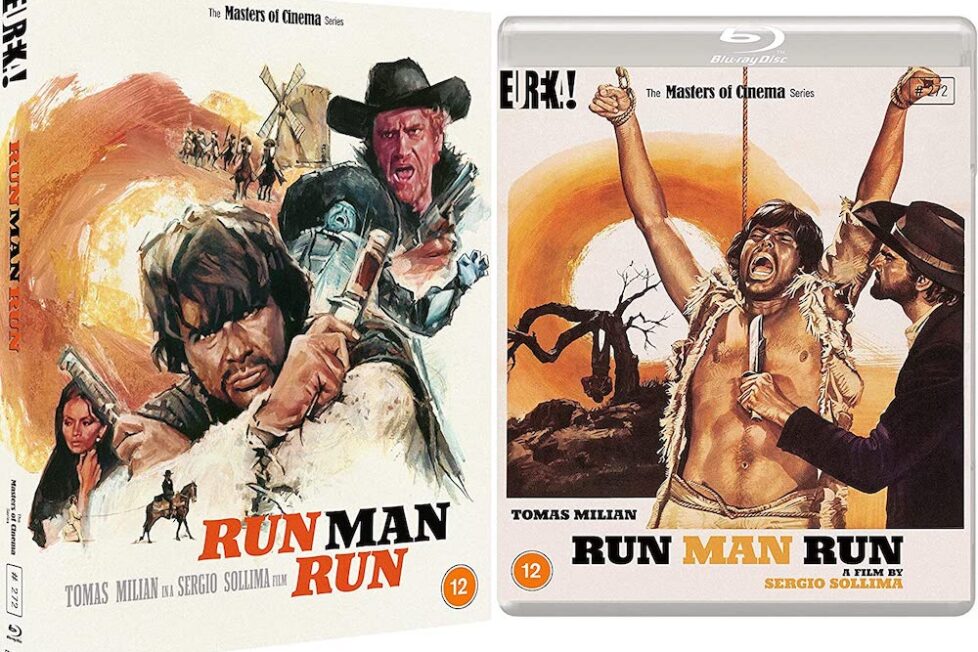

RUN, MAN, RUN (1968)

Several competing groups and mavericks hunt a gold treasure worth $3,000,000...

Several competing groups and mavericks hunt a gold treasure worth $3,000,000...

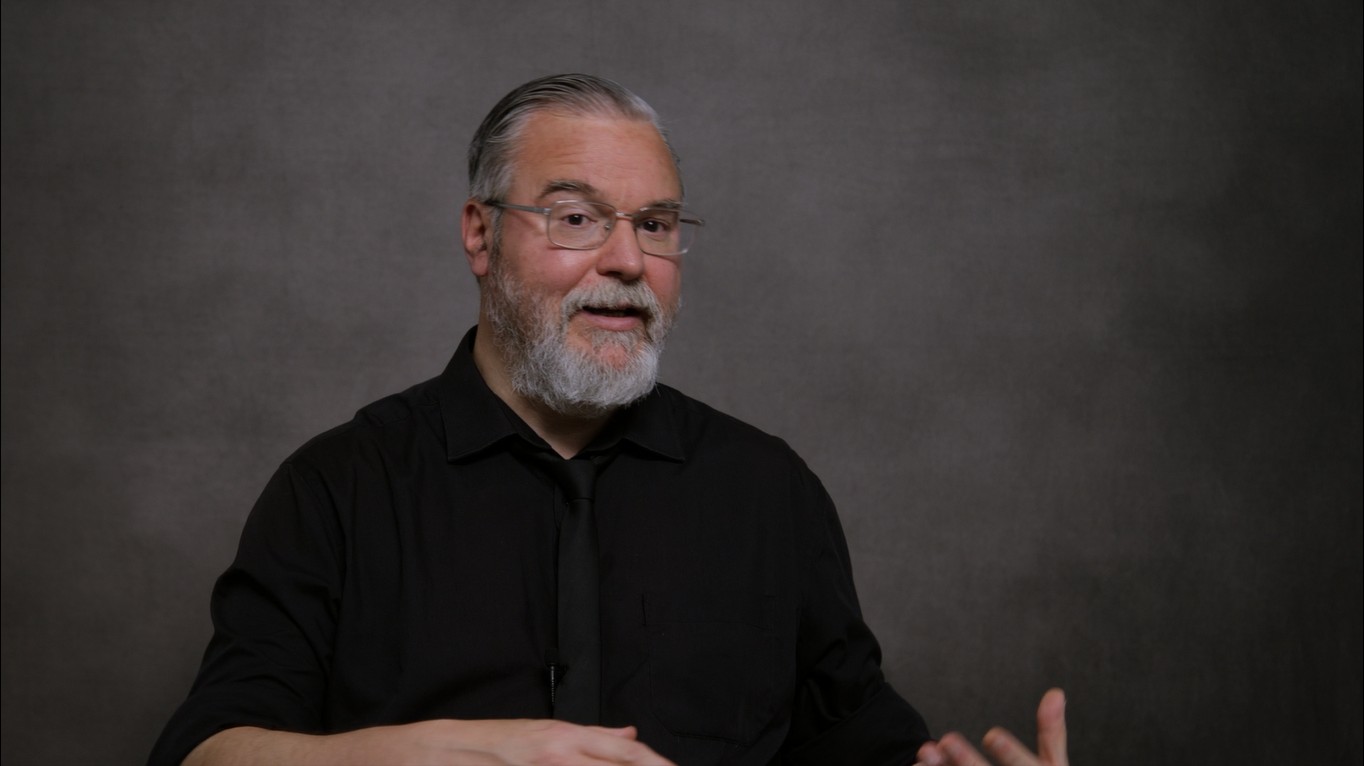

Run, Man, Run / Corri uomo corri is like an all-you-can-eat buffet, serving up a bit of everything one would expect from a spaghetti western, and proving to be one of the more satisfying out of the hundreds made in the genre’s heyday. This was writer-director Sergio Sollima’s final contribution to the genre and the last instalment of his loosely linked trilogy of so-called Zapata Westerns—the first being The Big Gundown (1966), followed by Face to Face (1967)—with Run, Man, Run offering a pleasingly open-ended conclusion. Each works as a standalone story because narrative continuity is tenuous, except for the historical backdrop of the Mexican Revolution and Tomas Milian reprising his role of Cuchillo from the first instalment in the third. That’s after playing the unrelated character of Solomon ‘Beau’ Bennet in the second.

After the huge success of The Big Gundown, the popular Cuchillo character was considered enough of a bo -office draw for Sollima to adapt the third screenplay into a vehicle for this unconventional hero. There aren’t too many examples of the Mexican peon taking centre stage, though one precedent that springs to mind is My Name Is Pecos (1966). Likewise, Run, Man, Run opens in familiar territory with a lone horseman entering a wide shot of desert landscape, at least Cuchillo has managed to keep his horse alive—which is more than can be said of the hapless Pecos (Robert Woods) who simply carried a saddle.

He passes a tableau of death involving a soldier propped up with a sign proclaiming he was a soldier of General Diaz, his arm raised to indicate three hanged Mexicans the sign claims were his ‘assassins’. It seems Cuchillo is used to such scenes and continues into a seemingly abandoned town, recognisably the same location that features in the opening to A Fistful of Dollars (1964). The rousing score also helps the unmistakable genre atmosphere, being a collaboration between Bruno Nicolai and Ennio Morricone who, due to contractual wrangling, wasn’t initially credited.

Through a doorway, Cuchillo spies a table set with chilli beans and tortilla… so, as there’s no one about, he hungrily helps himself and wanders out the other side of the adobe, finding himself in front of a firing squad. His unexpected, somewhat nonchalant appearance is enough to trigger momentary confusion during which he and some of the villagers lined-up for execution manage to scatter and escape.

It’s a wonderful opening gambit that sets the tone, establishes milieu, quickly sketches out Cuchillo’s character and sets up many themes that we’ll be revisiting. Not least the basic human need for food which motivates him on several occasions throughout. In fact Run, Man, Run can be seen as a cinematic discourse on Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs with Cuchillo clambering his way toward the apex of the pyramid.

On his return to his hometown, he finds another of his basic needs frustrated when he’s welcomed with a slap in the face by the feisty Dolores (Chelo Alonso). He decides a gift of gold may appease her and, after a brief scout about, presents her with a fine pocket watch. However, as she reads out the inscription commemorating Sheriff Nathanial Cassidy’s bravery in taking down 20 outlaws, Cuchillo is quick to guess who the tall man in black (Donald O’Brien) standing right behind him is! Another fine example of Sergio Sollima’s sleek storytelling and light touch. In fact, for a film about a knife-wielding peasant fighting for his life and the freedom of his oppressed country, there’s a generous helping of humour throughout.

It’s not long until Cuchillo ends up in a cell and, when he asks the jailer if his cellmate is dangerous, he’s told “… very, Mr Ramirez is a poet.” What seems like a throw-away jibe also introduces the idea that words, and information, can be very ‘dangerous’ to the establishment. So, it’s a surprise that the revolutionary poet, Ramirez (José Torres) has been granted a presidential pardon and will be released in the morning. It’s even more unexpected that he then explains to a confused Cuchillo that he’ll pay $100 for his help in escaping before dawn. Turns out that the recent influx of tough-looking strangers in town, including Cassidy, have been attracted by some $3M in gold that only Ramirez knows the whereabouts of. His pardon is effectively a death sentence, part of the president’s plan to ensure funds intended for the revolution are diverted elsewhere.

When Ramirez is betrayed by rebel compadres now turned bandits, catching a bullet in the cross-fire, he whispers something to Cuchillo with his last breath and pushes an old revolutionary newspaper into his hands. From here on, it’s a variation of familiar Euro-western themes we’ve already seen in Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)—competing factions with ambiguous motivations in a treasure hunt, bluffs and double-bluffs about who does and doesn’t know where it might be, and uneasy alliances. Milian’s Cuchillo isn’t as cool as Eastwood’s ‘man with no name’ (his poncho’s in a much worse state for one thing) and comes across more like Wallach’s ‘bad’ whilst Cassidy has the cold stoicism of the ‘good’ but could just as easily turn out to be a Lee Van Cleef style ‘ugly’, sharing the same dark sartorial tastes.

One of the things that marks Run, Man, Run apart from the majority of its contemporaries is the presence of two interesting women who turn out to be key players. Delores is more than the stereotypical Latina firecracker and sets off in pursuit of Cuchillo to watch his back and ensure he doesn’t get the money she believes will be a curse. Perhaps misguidedly, she comes to an arrangement with two French mercenaries, Colonel Michel Sévigny (Marco Guglielmi) and Jean-Paul (Luciano Rossi) who represent the foreign intervention in the Mexican revolution.

This interpretation is reinforced in one of the most memorable and symbolic scenes in which they capture Cuchillo and strap him to the sail of a windmill. On each slow turn he’s brought into reach for a brief brutal beating in an attempt to extract the location of the gold. Literally, this is a repeating cycle of revolution where foreign powers cause suffering to the native inhabitants of a land in order to extract some sort of profit.

The second woman in Cuchillo’s life is Penny Bannington (Linda Veras) whom he finds digging a grave out in the desert. It’s another of the film’s many memorable and visually striking scenes—a blonde woman appearing out of the ground behind the dark suited corpse of a stranger. When asked who killed the man, she explains that he died of an illness. Cuchillo is surprised but shrugs it off, “one can die that way, I suppose,” he admits before lending a hand. He learns that Penny is a Sergeant in the Salvation Army intent on preaching to the suffering peasants and feeding them with her wagon of supplies. Cuchillo is swift to offer his services as a replacement for her deceased assistant—yet another occasion when the promise of food is a major deciding factor, that and a way to travel incognito.

Cinematographer Guglielmo Mancori ensures that the expansive terrains are captured with clarity and an impressive depth of focus. Sometimes actors loom larger-than-life in the foreground as tiny specks of riders approach from the distance. There’s a satisfying variety of visual textures, too, from bleak beige desert to stark white snowscapes, plus a particularly well-shot showdown in a deserted town at night. The combinations of close-up and long-shot sometimes works as an expressionistic commentary on the shifting power gradients between characters, particularly in the three-way finale involving knife, revolver, and rifle.

The relatively simple puzzle-plot all fits nicely together with enough invention to keep it interesting along with some serious political subtexts. Sergio Sollima was an auteur with communist leanings and nearly always injected some anti-capitalist message into his films. Here, he challenges the expected status transactions that tend to govern human relationships. As with his two preceding westerns, this examination is fractal, beginning with the personal exchanges between individual characters, reaching the political terrain of unstable governance, before considering the international influences from foreign nations. Although Run, Man, Run is the lightest of his three westerns, it’s probably the most overtly political.

It also presents and interesting take on identity politics that seems aware of the intended audience as well as cast choices. Bear in mind Italy has its own revolutionary history, leading to unification under Giuseppe Garibaldi in the 19th-century—50 years ahead of the Mexican revolution—-and had, more recently, defeated their own fascist dictator, Benito Mussolini, albeit with the catalyst of a world war. Much of the location filming took place in Spain, during the latter years of another fascist regime under Francisco Franco.

Mexicans played by Spanish actors always works pretty well but in Tomas Millian, we have an actor of Cuban origin, born and raised against a backdrop of political turmoil that would spark the revolution led by Fidel Castro in the 1950s. By then, Milian had emigrated and was pursuing his ambitions to become an actor, initially making an impression on the New York stage before transitioning to the screen in the late-1950s, working between the US and Italy. By the time he took the role of Cuchillo he had around thirty screen credits to his name and would rack up another 90 or so until retiring in 2014.

Watching Sollima’s triptych back-to-back may offer a nicely immersive experience but could be disconcerting as the character of Cuchillo has changed during the interim. In The Big Gundown, he’s more ambiguous, cleverly manipulative, world-wise, and a little world-weary. When we meet him again in Run Man Run, he’s an opportunistic dreamer who relies on luck a lot of the time and allows events to sweep him along. Necessity has made him a petty thief but, at heart, he’s a good man who believes life should be fair even though he’s fully aware it’s not. He certainly puts his own interests first, at least to begin with, but when faced with a chance to make a real difference for the revolution, he’s clearly wrestling with a moral dilemma and part of the fun is guessing which way he’ll run.

ITALY • FRANCE | 1968 | 120 MINUTES | 2.35:1 | COLOUR | ITALIAN • SPANISH

I’m so happy that the resurgence of interest in Italian pulp cinema has created enough of a new audience that boutique imprints like Eureka! Entertainment are now scouring the vaults for cult classics and overlooked genre gems like this. Italian horror’s always had a following, but it wasn’t all that long ago when the giallo was a truly obscure genre and the only spaghetti westerns that got any real exposure were Leone’s deservedly iconic Dollar trilogy.

Recently, things have changed and not only are such films being re-released, but they’re being given beautiful digital restorations. This double-disc Blu-ray package of Run, Man, Run looks fantastic with punchy colours taken from a new 4K scan which represents the film’s first proper release outside of Italy, presented here in two versions. The full, 120-minute, director’s cut is on Disc 1 and is the key selling point of this handsome package. The theatrical cut on Disc 2, at 85-minutes, seems brash and rushed—-only worth watching for comparison and its excellent audio commentary by Howard Hughes and Richard Knew.

director: Sergio Sollima.

writer: Sergio Sollima & Pompeo De Angelis.

starring: Tomas Milian, Donal O’Brien, Linda Veras, Chelo Alonso, John Ireland & Marco Guglielmi.