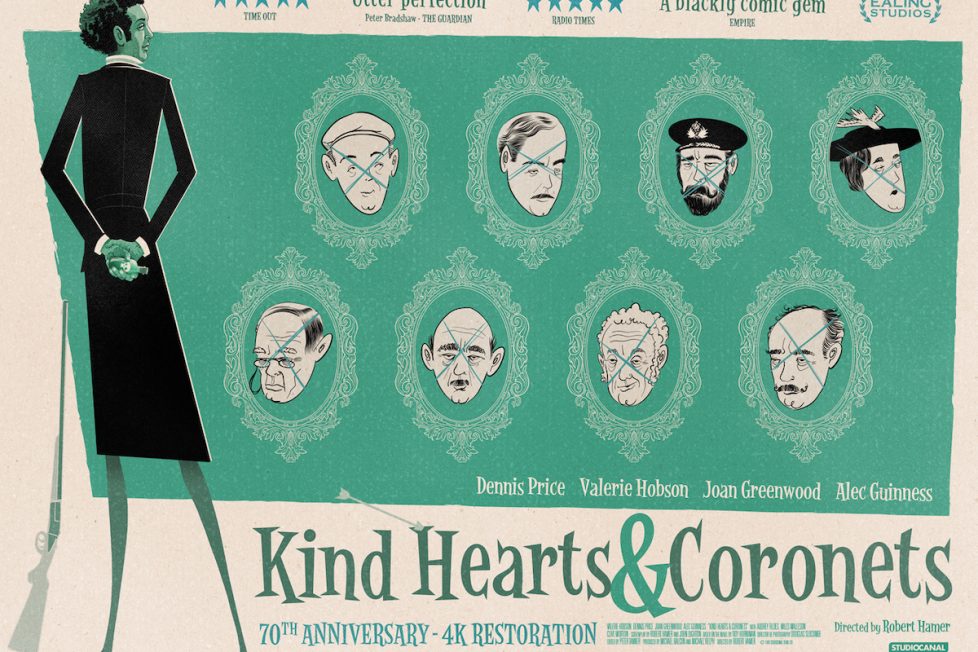

KIND HEARTS AND CORONETS (1949)

A distant poor relative of the Duke of D'Ascoyne plots to inherit the title by murdering the eight other heirs who stand ahead of him in the line of succession.

A distant poor relative of the Duke of D'Ascoyne plots to inherit the title by murdering the eight other heirs who stand ahead of him in the line of succession.

Kind Hearts and Coronets, Ealing Studios’ celebrated black comedy from 1949, was released the same year as two other highly regarded Ealing comedies—Passport to Pimlico and Whisky Galore!—topping a very creative run for producer Michael Balcon. Despite a diverse back catalogue, these three films forever associated Ealing with the genre. For its 70th anniversary, StudioCanal has re-released the film into cinemas and on Blu-ray, having restored the original 35mm film elements in 4K resolution.

Its anniversary offers us a chance to again appreciate the work of director Robert Hamer, who left behind a small but distinguished body of work in a career and life tragically marred by alcoholism and his untimely death at the age of 52. He started out as a cutting room assistant for Gaumont-British in 1934 before joining Alexander Korda’s London Films at Denham. He worked on a number of films for Erich Pommer, who’d formed a production company with actor Charles Laughton, and edited Vessel of Wrath (1938) and Hitchcock’s Jamaica Inn (1939).

At the GPO Film Unit, he met fellow documentary director Alberto Cavalcanti who, when he moved to Ealing, recruited him in 1940 to work as an editor on several war films and the George Formby picture Turned Out Nice Again (1941). Studio boss Balcon saw Hamer’s potential and promoted him to associate producer. When he oversaw the production of the Will Hay comedy My Learned Friend (1943) he worked with writer John Dighton, who had contributed to many Ealing war films including Went the Day Well (1942). The Hay comedy, as Gavin Collinson noted, with its humour “revolving around a sequence of grisly murders” foreshadowed the Wildean, bleakly satirical Kind Hearts and Coronets, the script on which Hamer and Dighton would later collaborate.

Hamer’s directorial output, from his debut proper with ‘The Haunted Mirror’ segment in portmanteau supernatural film Dead of Night (1945), followed by the Patrick Hamilton inspired low-life and family melodrama of Pink String and Sealing Wax (1946), to the gritty expression of female identity and domestic structures in It Always Rains on Sunday (1947), seemed to be leading up to Coronets, perhaps Ealing’s most barbed exploration of careerism, sexual repression and class division. However, Dighton was brought onto the film at a later stage after writer Michael Pertwee (brother of Jon) had brought actor-manager impresario Roy Horniman’s 1907 novel Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal to Balcon’s attention in 1947.

Rank, the son of a Jewish commercial traveller, tells the story in the form of his memoirs, composed in his condemned cell after he was arrested for the murder of one of the six people who stood between him and the inheritance of the Gascoyne peerage. Simon Heffer, in an introduction to the 2009 edition of the novel, suggests Horniman “explores and parodies the anti-Semitic attitudes of Edwardian England” as Rank cold-bloodedly kills his victims. He sets out both to attain a position that his betters have already achieved and fulfilled the designs he has on Sibella, a woman “unable to control her desire to set men at each other’s throats” and who exacerbates Rank’s psychopathic tendencies by spurning him to marry Lionel Holland.

Rank is not a sympathetic character and his murder spree is a dark, disturbing litany that includes (and this does not appear in the film for very good reason) the murder of a baby by wiping its face using a handkerchief permeated with scarlet fever bacteria. The ending of the book and the film are very different. Rank survives his incarceration when a former mistress, Esther Lane, confesses to the murder he’s been arrested for in her post-suicide note. Sibella becomes his latest mistress, he marries the sister of one of his victims and produces an heir. As Heffer acknowledged of the book’s half-Jewish central character, “the controversy will always be about its antisemitism… it skirts dangerous territory, and possibly even wades into it.” While he also argued it was a satire about antisemitism, critic Peter Bradshaw saw it as “specifically satirising English attitudes to the career of Benjamin Disraeli: his wicked antihero at one stage relaxes with a copy of Disraeli’s novel Vivian Gray.”

The book, although witty and subversively Wildean, therefore contained potentially offensive material. Balcon, son of Jewish immigrants, clearly found it difficult to see how Ealing could produce a comedy about a half-Jewish serial killer when World War II had ended just two years prior to Pertwee’s suggestion the book was suitable for adaptation. Balcon was deeply concerned about the tenor of the book but asked Pertwee to write a treatment. Hamer had always wanted to make a film about Henri Désiré Landru, the French serial killer who murdered seven women over a four-year period, but the project was abandoned by Ealing when Orson Welles approached Chaplin about making a film inspired by Landru’s story, released as Monsieur Verdoux (1947). Balcon probably had this in mind when he thought of Hamer for Coronets.

Hamer and Pertwee didn’t get on and, after some initial draft screenplays, Pertwee bowed out. He was not credited for his work. Hamer and Dighton worked together and transformed Horniman’s book (credited with a certain unease and reluctance in Coronets’ opening titles ) and made the protagonist a suave yet coolly detached dandy whose mantra is “revenge is the dish which people of taste prefer to eat cold.” Rank became Louis Mazzini (Dennis Price), a half-Italian draper’s shop assistant, who sets out to avenge his mother (Audrey Fildes). Having married beneath her to an Italian opera singer, she has been cruelly ostracised by her aristocratic family, the D’Ascoynes and thus been deprived of her and her son’s inheritance.

After his mother’s death, Louis sets out to rectify this calumny and claim his inheritance by bumping off the eight D’Ascoynes (all played by Alec Guinness) in line to the dukedom of Chalfont. As he inveigles his way from mere shop assistant to private secretary to Lord Ascoyne D’Ascoyne, his upward mobility convinces his childhood sweetheart Sibella (Joan Greenwood) that her dismissal of his original marriage proposal was a little too hasty. Although married to his school friend Lionel Holland (John Penrose), she begins an affair with Louis as he murders his way up the family tree. Ironically, after blowing up Henry D’Ascoyne, a keen amateur photographer, he charms Henry’s widow Edith (Valerie Hobson) and plans to make her his duchess. However, Sibella proves to be as equally manipulative when Lionel is found dead after Louis refuses to save him from bankruptcy. Louis is arrested for one murder he never committed and she sees it as an opportunity to blackmail him. As Bradshaw notes of this ironic climax, “this is a masterpiece of suspense, much better than Israel Rank’s final anticlimactic and implausible sloppiness.”

The film owes its devious and subversive pleasure to a number of factors. The performances are a delight and are a testament to Hamer’s recognised skill with actors. For many years, Coronets‘ status owed much to Guinness’s wonderful appearances as the eight D’Ascoyne family members (nine if you count a portrait that Louis refers to at the beginning of his spree), and his work is best encapsulated in the sequence where Louis appraises the six remaining D’Ascoyne family members sitting together in church. A superb sequence overseen by cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, it took days to put together as Guinness had to be made up and costumed as each of the D’Ascoynes, with each performance combined in-camera through multiple exposures. This required a locked-down camera, so fiercely guarded by Slocombe that he slept next to it overnight during production! Guinness also kept a note on his performances, listening in with the editors in the cutting rooms as the film was assembled.

What tends to be forgotten is how exceptional Dennis Price is in the lead role as Louis Mazzini. The entire film is held together by his narration, an extension of the memoirs he completes in his prison cell at the beginning of the film to facilitate the film’s flashback structure, one akin to Horniman’s book. It’s through Louis that we witness the events of the film, beautifully gathered together in the script’s tight, witty dialogue and characterisation and one decorated with references to Longfellow and Tennyson. Much of the film’s sardonic, Wildean humour is conveyed through his performance, often topped with zinging one-liners delivered as we watch with transgressive glee the demise of yet another D’Ascoyne snob.

Indulging in a dirty weekend, Ascoyne D’Ascoyne and his mistress plunge to their demise over a weir in Maidenhead and, after his intervention with their punt, Louis reflects “I was sorry about the girl but found some relief in the reflection that she had presumably, during the weekend, already undergone a fate worse than death.” As suffragette Lady Agatha D’Ascoyne’s leaflet drop in a hot air balloon is curtailed by Louis’ immaculate archery skills, he quips “I shot an arrow in the air; she fell to earth in Berkeley Square.” These are moments that skew our moral certainty with their use of language, of poetry and irony as each D’Ascoyne gets what’s coming to them. Price also matches Guinness by donning disguises and, as the Bishop of Matabeleland, he poisons the after-dinner port of the Reverend Lord Henry D’Ascoyne. Balcon apparently received a rather indignant letter some years later from the representatives of the real Bishop who had endured some embarrassment since the film’s release. This was despite the fact that he hadn’t seen the film and the post didn’t exist when the film was released in 1949.

The arc of Louis’ character, for the most part, evinces a great deal of sympathy from viewers until he polishes off Ethelred D’Ascoyne, the man responsible for refusing to allow Louis’ mother to be buried in the family vault. There the tone shifts from dark frivolity and briefly reveals Louis as the cold-hearted killer beneath the desire for social mobility. This swift rise to power is also documented in the growing profusion of elaborate costumes that Price wears to mark his progress. After Ethelred has a poacher whipped, Louis simply lures Ethelred into a man trap while grouse shooting and then lets him have both barrels. It’s here we get the true measure of Louis’ hatred for this particular D’Ascoyne and it’s a good example of how Price managed to allow this anger to seep out intermittently from under the suave, sophisticated veneer of Louis Mazzini. It’s his best ever performance, very subtly toying with the aesthetics and linguistics of Wilde, with Louis as a smoke and mirrors reflection of Price and Wilde’s tragic personal lives.

It’s emerged that perhaps Balcon reined in Louis’ more sadistic intent. As Matthew Sweet attests in his recent discovery of the original draft script, the death of Henry D’Ascoyne, blown up when Louis puts petrol in the photographer’s darkroom lamps, was much more brutal. “In the script, he [Henry] is not so nice. He is having an affair with the fiancée of the village blacksmith. Louis follows him to his place of assignation and caves in his skull with a hammer.” The original draft also depicts that the arrogant Ethelred is instead thrown out of the castle window and drowns in a lake full of hungry swans. Louis deflects tea-party guests from the conflagration with a discussion about “whether foie gras is fatal to swans.” At the behest of the US censor, Balcon had these scenes rewritten, perhaps in fear that the script was veering too closely to its provocative origins.

The US censor also took umbrage at Louis’ pithy bon mot as Ascoyne D’Ascoyne and his affair tumbled into the weir at Maidenhead and their British equivalent also baulked at the double meaning in Louis’ wedding present to Sibella and Lionel. In the uncut sequence, the camera tracked along the table of wedding presents and held on a close-up of a pair of antlers with a card showing they’re from Louis. Sound editor Peter Musgrave noted “it’s actually an old Italian sign for a cuckold. So Louis has presented this to the couple, having cuckolded the guy before she’s even married him, which in those days was utterly shocking. And the censor took the close-up out.”

The transgressive nature of the film threads into the performances of Joan Greenwood as Sibella and Valerie Hobson as Edith. The two women in Louis’ life are actually the barometer by which we can measure his ascendance to D’Ascoyne snobbishness. On the one hand is Sibella, the purring manipulative mistress… and on the other is Edith, the solid, good woman. They are the markers between career and love, family and establishment, monogamy and licentiousness. Again, Anthony Mendelson’s costumes for both characters wittily and flamboyantly reflect their qualities. Balcon was flustered “by the powerful erotic charge of the scenes involving Greenwood’s delectably sensual Sibella. He demanded that they be toned down.” It developed into a row with Hamer that seemed to reflect the stresses and strains that his career at Ealing was subjected to. On the other hand, given Hamer’s ability to get the best out of actors, Hobson offers “an appealing warmth often lacking in her other screen appearances.”

With Louis, there is a sense the film, in its conflicted irony, “acts as an agent for quite radical class resentments. The D’Ascoynes are felt as obstacles in the way of him and all of us.” They are definitely the obstacles between Louis’ kindhearted mother, a D’Ascoyne as the legitimate source for vengeance, and his attempt to replace the patriarchal arrogance of the family that denounced her. However, Louis becomes the very thing he intends to chop down in his determination to become the Duke of Chalfont, journeying from a witty anti-hero ready to “tear society apart by applying to it the logic of its own corruption”, as Charles Barr suggested, to as equally ruthless and repressed a figure as Ethelred D’Ascoyne. Certainly, the film can be seen as an attack on the establishment of the time but rather than a quiet revolution from a working-class perspective, as in many Ealing films of the period, its an assault from within their own aristocratic ranks at an edifice that, in 1949, survives beyond the post-war settlement.

Coronets culminates with a brilliant satirical twist. When Sibella blackmails Louis and produces Lionel’s suicide note, he receives a last-minute pardon. He’s freed from prison (populated by the appropriately Ealing-esque Governor, played by Clive Morton, and the hangman, a lovely turn from Miles Malleson) and is met by a reporter (Arthur Lowe) from Titbits magazine who offers to publish his memoirs. With a start, Louis suddenly realises his memoirs, revealing the extent of his criminal project, are still in his cell. The camera closes in on their title page, taking us back to the opening of the film and the close up ambiguously seals in the paradoxical tale and its radical trajectory. In the British cut, the film leaves us in limbo to ponder Louis’ fate. Will someone read the memoirs? Will he be arrested again?

It’s a delicious final tease in a film that constantly teases with its irony and satire, poking morbid fun at the aristocracy and their snobbish attitudes to those beneath them whilst simultaneously opening up a can of worms about morality and sexuality, the power of memory and the performance of the self, and how an individual can justifiably distance himself from the most heinous actions.

All of this is presented in a lovely, very detailed transfer, downscaled from 4K to 2K for 1080p Blu-ray. While it’s not a significant improvement on the previous release, the image, a striking testament to Douglas Slocombe’s cinematography and to Hamer’s cool, distancing style (despite many critics at the time bemoaning that Hamer didn’t appear to have given the film a recognisable style) is robust and devoid of marks or white spots. It also sports the requisite film grain and high contrast. The level of grain does tend to pulse in and out of the presentation at times and some of the deeper blacks tend to get crushed but overall this is a handsome presentation.

Sadly, some of the special features from the 2011 release, BBC Radio 3’s The Essay—British Cinema of the 1940s: Kind Hearts and Coronets and the BECTU History Project interview with Douglas Slocombe haven’t been ported over to this newer release. However, the following are included in this 70th-anniversary issue:

director: Robert Hamer.

writers: Robert Hamer & John Dighton (based on ‘Israel Rank: The Autobiography of a Criminal’ by Roy Horniman).

starring: Valerie Hobson, Dennis Price, Joan Greenwood & Alec Guinness.

I am indebted to the following articles and books: