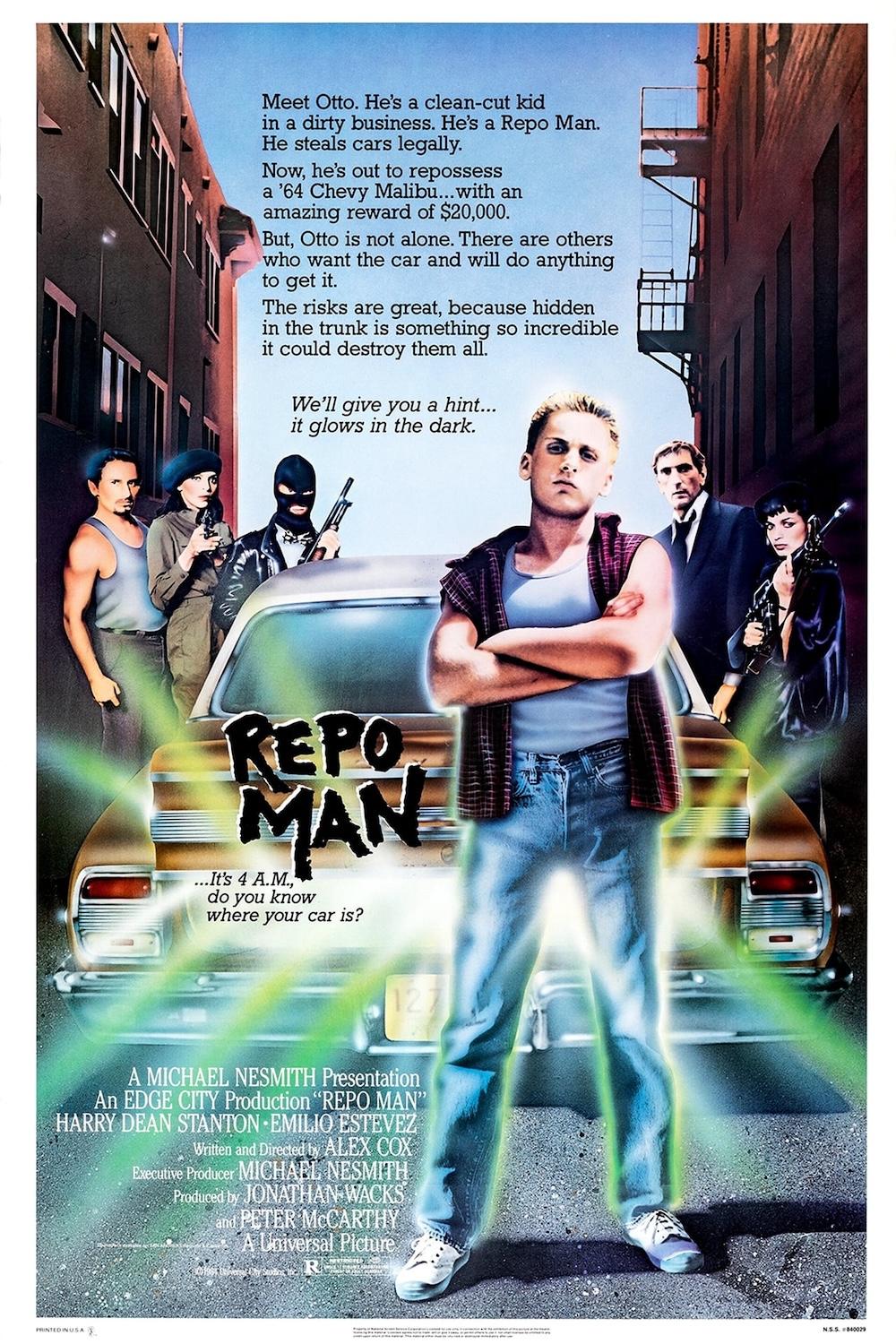

REPO MAN (1984)

A young punk, recruited by a car repo agency, finds himself in pursuit of a Chevrolet Malibu with a huge, $20K bounty--and something otherworldly stashed in its trunk.

A young punk, recruited by a car repo agency, finds himself in pursuit of a Chevrolet Malibu with a huge, $20K bounty--and something otherworldly stashed in its trunk.

Repo Man is very much a product of its time yet still feels fresh and audaciously original. There are no obvious precursors to the dazzling debut from writer-director Alex Cox that perfectly reflects the anxiety and ennui of ‘the blank generation’. Nor do any successors spring to mind—nothing quite like it has been, or could be, made since.

That said, Cox himself has been touting the idea of a sequel since the mid-1990s. An abortive attempt, titled Waldo’s Hawaiian Holiday, went into production in 2005 but ultimately ended up being published as a graphic novel in 2008. Cox wrote and directed the spoof film, Repo Chick (2009), retreading similar ground but with a female lead and a plot involving kidnapping in addition to repossessing planes, trains, and automobiles. This was a straight-to-DVD release, shot on a budget using the visual language of television commercials with all the locations added using a simple greenscreen process.

So, after 40 years, it was a pleasant surprise that Alex Cox announced an official sequel is currently in production. With producers already on board, Kiowa Gordon (the Twilight saga) has been cast as Otto in Repo Man 2: The Wages of Beer. However, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. While we eagerly await further developments, why not let the luminous Chevy Malibu transport us back to 1984…

I remember reading sociopolitical analyses at the time, which surmised that 1984 was the most likely year for a nuclear apocalypse. Back then, I was still in college, and everyone I knew seemed prone to nuclear nightmares, likely partly instigated by the terrifying television movie Threads (1984). This genuine, pervasive worry made the UK punk slogan, “No Future”, even more poignant.

The unifying paranoia of then-contemporary youth simmers beneath the surface of Repo Man, threatening to erupt into a full-blown apocalypse. Early drafts of the screenplay featured a runaway chain reaction triggering the nuclear annihilation of Edge City (a.k.a. Los Angeles) and beyond. However, this ending would have been overly serious, clashing with the film’s flippant tone established through redrafting. It would have been a cop-out, relying on the easy, even lazy, trope of ending dystopian science-fiction with a bang. Repo Man, however, avoids both a whimper and a bang, opting instead for a more ambiguous conclusion. More like a hoorah! But we’re not sure what for. Freedom, transcendence, or simply escape from ‘what is’ into ‘what else’?

Alex Cox penned the first version of the screenplay as an extension of ideas he’d already explored while at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) in his film school graduation short, Edge City: Sleep is for Sissies (1977). He circulated his Repo Man script along with a short, comic-style storyboard that attracted the attention of Michael Nesmith, who had extensive contacts in the entertainment industry and was seeking projects independent of his band, The Monkees. Nesmith, already producing TV shorts and promotional videos for artists like Lionel Richie, had just completed Timerider (1982), his first feature-length film as a producer. He secured a “negative pick-up” deal with Universal Studios, which guaranteed a $1M budget but only required payment upon completion of the film. While not ideal, this arrangement facilitated fundraising and maintained the film’s independent status.

The film opens with one of its strongest components—music—featuring a driving instrumental version of the main theme by Iggy Pop accompanied by a band comprising Nigel Harrison and Clem Burke (both known for their work with Blondie) and former Sex Pistols member Steven Jones. Instant punk cred, though we don’t get to hear the full song until the end credits, and it’s worth the wait.

We meet the sweating, inanely grinning J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris) as he weaves his 1964 Chevrolet Chevelle Malibu along a stretch of the iconic Route 66. His erratic driving draws the attention of a police motorcycle patrol. When the officer (Varnum Honey) pulls the car over and demands to see what’s in the trunk, Parnell cordially replies, “Oh, you don’t wanna look in there,” which is a sure way to compel a cop to do exactly that, an example of how simple refusal can be used to push back against authority gradients. And what he finds in the trunk is a magnificent MacGuffin that rivals the mysterious box from Kiss Me Deadly (1955). A blinding light vaporises the man, leaving nothing but a pile of ash and a pair of smouldering boots as Parnell continues his drive through the Mojave Desert.

It seems Nesmith was a hands-on producer, heavily involved in development and working closely with the cast and crew. He even makes a couple of blink-and-you’ll-miss-them cameos in the movie. The now-famous smoking boots image, used on many Repo Man posters, was homaging a scene from Timerider but remains one of the truly great opening gambits. However, the film takes a few detours before offering any sort of explanation.

Instead, the story focuses on Otto (Emilio Estevez), who works in a supermarket alongside his friend, Kevin (Zander Schloss). They’re having a petty argument as they stack cans of sliced peaches. The store manager (Charles Hopkins) decides they’re not working hard enough and fires them both, but not before the security guard (Luis Contreras) gets a chance to assert his dominance and bully them a little.

Now, one might assume that the store manager and security guard are incidental characters, quickly forgotten. But what makes Repo Man so intriguing is how seemingly unrelated events end up weaving together in a strange pattern of coincidences. It’s as if life may be governed by some sort of mysterious underlying pattern. Or perhaps not. Either way, the search for meaning is the key theme here, and Alex Cox has great fun along the way, incorporating plenty of audio-visual gags.

We’ve already seen the blue and white minimalist labels on the store goods, which will be a recurring motif. Look out for the ubiquitous non-product placements labelled simply “food,” “beer,” “cornflakes,” or “butyl nitrate,” and pay attention to the incidental soundtrack as the background televisions and radios provide a clever commentary on what’s happening or is about to happen.

This narrative use of seemingly random broadcast material is a major clue to one of Alex Cox’s influences: William Burroughs, a transgressive author of experimental science fiction who experienced a resurgence of interest in the early-1980s. Burroughs, along with collaborator Brion Gysin, developed the “cut-up method,” which treats printed text much the same way an artist approaches collage, rearranging elements to form new prose and often revealing unexpectedly cogent narratives.

Burroughs took this concept further, utilizing the audiovisual media that surround us by remixing it in various, inventive ways. The simplest approach involves switching through television channels at set intervals, or randomly, noting down what’s being said or shown. This process allows one to analyse the stories or hidden wisdom that this disrupted information stream might imply.

Of course, this approach to language parallels the editing of a film, which, by its very nature, is a form of cut-up composition. Cox includes several stylistic nods to Burroughs’ work, with a couple of explicit references. In a hospital scene, the PA system can be heard calling for “Doctor Benway,” a recurring mad surgeon character in the author’s works, most notably his 1959 novel Naked Lunch.

After learning his girlfriend is cheating on him with his best friend, Duke (Dick Rude), Otto spends the night drowning his sorrows in beer on a stretch of disused railway. The desolate scene mirrors his sense of being lost and going nowhere, serving as a powerful symbol of both personal and economic decline. It also echoes the old saying, ‘They came from the wrong side of the tracks.’ As dawn approaches, he wanders away, muttering the titles of television shows and paraphrasing lyrics from the classic Black Flag track “TV Party.”

It’s a particularly poetic scene, with the 4th Street Bridge silhouetted against the dawn as its backdrop. This is just one of several beautiful shots, and considering budgetary constraints and a rough-and-ready shooting schedule, the cinematography is impressive throughout, due to the pairing of Robby Müller, credited as director of photography, and Robert Richardson, as cameraman and Second Unit Director.

Müller was already a seasoned cinematographer, a favourite collaborator of Jim Jarmusch and Wim Wenders—perhaps that’s why Repo Man and Paris, Texas (1984) both open with impressive shots of an expansive desert? It was early in the career of Richardson, who would go on to work with Oliver Stone and Martin Scorsese and become Quentin Tarantino’s go-to cinematographer.

Toward the climax of Repo Man, there’s a shocking outbreak of high-impact, bloody violence during one of several grocery store hold-ups that certainly foreshadows a similar approach to be seen in Tarantino’s movies.

As Otto wanders through the sprawling suburban dereliction, he’s curb-crawled by a 1959 Ford Model F-350, driven by Bud (Harry Dean Stanton), who offers him $25 to help move his wife’s car out of the run-down neighbourhood. He spins a yarn about her being taken to the hospital. Otto reluctantly agrees and doesn’t realise he’s just been recruited as a repo man until the irate owner of the white Oldsmobile Cutlass—who is not Bud’s wife—tries to stop him from taking the car.

Harry Dean Stanton had already been around for a while, accumulating around 120 credits to his name, including many uncredited appearances, before being cast as Bud. A hardworking character actor since his 1954 debut, 30 years earlier, he could be glimpsed in a string of classics.

While he wasn’t originally involved in Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars (1964), Stanton played the prison warden who gives the Clint Eastwood stand-in (dressed in a poncho) a mission to clean up a town south of the border. This ill-conceived, four-minute prologue was added by the ABC television network for their broadcasts of the movie in the mid-1970s. The network exposure, however, coincided with Stanton’s transition from mainly television bit-parts to feature films, having just appeared in Sam Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid (1973) and John Milius’s Dillinger (1974). He stood on the cusp of cult stardom, which was soon confirmed by his back-to-back roles in John Huston’s Wise Blood (1979) and Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979).

However, for the arthouse crowd, 1984 marked Stanton’s peak year. He delivered a double whammy with a subtle, yet incredibly deep lead performance as Travis Henderson in Paris, Texas and a complete contrast in Bud, the repo man’s repo man. Reputedly, there was some on-set friction between the 59-year-old actor and the young, punk, first-time director, 30 years his junior. Nevertheless, his performance formed the backbone of the film, and he would eventually be recognised as one of the greatest actors of his generation. Topping his seven-decade career, his final lead role was the achingly poignant, though ultimately positive, Lucky (2017). That tour de force saw him play an old man confronting his mortality.

Repo Man was filmed in several unglamorous locations amidst the dilapidated urban sprawl of Los Angeles, much of which has since been cleared and developed. This was likely done to avoid expensive filming permits, but the junkyards and back alleys perfectly suited the politically pointed story—a visual shorthand for moral erosion and divided society in a state of collapse under the Reagan administration. Much of the urban landscape already appeared post-apocalyptic. There were two sides to the city, with the action taking place far away from Hollywood, Bel-Air, or Beverly Hills.

In the junkyard of the Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation, Otto encounters a motley crew of repo men. He’s offered a job and a “beer,” which he refuses by pouring the can onto the office floor. This act carries double the insult when we discover that each repo man is named after a well-known beer brand. We’ve already met Bud, and there’s also Lite (Sy Richardson), the boss Oly (Tom Finnegan), and yard mechanic Miller (Tracey Walter). These four key characters at the repossession agency were initially conceived with the members of the punk rock band Fear in mind, though the idea of casting them was quickly abandoned.

Otto decides to give up being a dropout and returns home to ask his television-enthralled parents, Johnathan Hugger and Sharn Gregg, about the money they’d set aside for his education. While Otto eats “food” straight from the can, his parents, lighting a spliff, explain that they donated all his college funds to a televangelist, Bruce White, to send Bibles to El Salvador. Within the first quarter-hour, we’ve been introduced to the main methods of oppression employed by a late-stage capitalist system: consumer-constructed desires, materialism, financialization, debt, mass media, and faith.

Otto signs up to become a repo man under the tutelage of Bud and Lite, who both expound their differing philosophies in stylish and highly quotable monologues. Cox wrote their dialogue based on conversations he’d had with a real repo man who happened to be his neighbour. He also showed an early cut of the film to an audience of repo men, who approved of their portrayal, but emphasised that the real repo world was even crazier and more fraught with violence and danger.

The life of a repo man is always intense because they repossess cars from people who have defaulted on making payments. Those whose vehicles are taken are usually not too happy to give up the things that enable them to travel to work and thus make the necessary money to make payments. This can lead to not being able to pay rent or the mortgage on their homes, which in turn could well lead to their family’s eviction. This is the consumer trap in a nutshell: the worker works to earn money to be materially successful but, ironically, that money is mostly spent on necessities, enabling them to work. And so, the cycle continues. Thus, Repo Man portrays the American dream as a recurring nightmare.

It’s also a loving, and damning, portrait of the American punk subculture of the era. It celebrates the scene’s anti-authoritarian, anti-conformist, and anti-capitalist agenda and showcases an impeccable selection of seminal bands on the soundtrack. During filming, Zander Schloss met and joined Circle Jerks, one of the most important early hardcore bands. The band also provides a few songs for the soundtrack and appears briefly, dressed comedically in tuxedos, performing a tongue-in-cheek acoustic version of “When the Shit Hits the Fan.” Otto mutters with dismay, “I used to like these guys…”

Alex Cox, though on the periphery of the subculture, recognised its diversity within a mutually supportive community. However, he didn’t shy away from satirising the conflicts and contradictions within it. After all, punk rock raises its middle finger to conformity, and self-reflection is included. He depicts punks as having social hierarchies and strata similar to the rest of society, taking the view that many so-called punks are simply young people, adrift in a challenging world.

They still possess human desires, wanting the same things as everyone else: a sense of belonging, reciprocal relationships, some stability, and everyday comforts. However, they lack the knowledge of how to attain these, consequently rejecting what previous generations have offered them, even when no practical alternatives exist. Despite their apparent nihilism, perhaps they harbour a deeper hope. They might believe that if enough people refuse to accept the status quo, something better will eventually emerge… maybe… one day.

The term “Blank Generation”, lifted from the title of Richard Hell and the Voidoids’ 1977 song, came to define a group of young people disillusioned with contemporary society. This label, encapsulated by the song’s reflection of widespread alienation, became a touchstone for the No Wave movement and applied to a group of radical American authors emerging in the late-1970s and early-’80s.

These writers, including Kathy Acker, William S. Burroughs, Lydia Lunch, Richard Miller, and Hubert Selby Jr., often pushed the boundaries of experimentation and provocation in their fiction, frequently employing disturbing and violent themes. Aiming to disrupt established literary conventions and challenge the status quo, their work reflected a deep dissatisfaction with both consumerist culture and broader societal structures.

While Repo Man is often compared to its immediate punk-cinema predecessors like Susan Seidelman’s Smithereens (1982) and Penelope Spheeris’s Suburbia (1983), it shares a closer kinship with the transgressive spirit of those earlier literary figures.

So by now, the viewer may well have forgotten about that hapless, disintegrated motorcycle cop, despite the opening scene’s visual impact. Don’t worry, though; Cox hasn’t. While driving a repossessed Cadillac Eldorado convertible back to the yard, Otto decides to pose as the rightful owner, hoping the prestigious car will impress a young woman he spots on the sidewalk.

She turns out to be Laila (Olivia Barash), who’s on the run from some suspicious-looking men in dark suits and mirrored shades. She may be just a crank, but it appears she has been recruited by a shadowy arm of the secret services to infiltrate UFO conspiracy groups—such as the United Fruitcake Outlet—putting her in a position to hear the word on the street about strange phenomena linked to aliens or alien artefacts that have recently disappeared from a secret government facility. Or… is the alien story simply more misinformation to deflect attention from some sort of experimental military technology that’s been stolen by the, shall we say, intellectually challenged J. Frank Parnell?

Apart from a few uncredited bit parts as a child actor, Repo Man was the feature debut for Olivia Barash, who was 18 years old at the time, having already amassed an impressive resume of at least 20 television roles including “Sylvia”—a notoriously controversial two-parter of Little House on the Prairie (1974-1983) in which she played an under-aged girl who’s raped, shunned, and dies when her assailant comes back for a second try. Her bravura performance ensured that she was in demand, and brought her to the attention of Alex Cox.

Here, Barash plays the ditzy teenage female lead. Later, we see her darker side as a lackey to Agent Rogersz (Susan Barnes), head of a ruthless and unscrupulous government agency. Rogersz wears a sequined glove to cover her bionic hand. Cox has since admitted that despite Rogersz being a cyborg, the budget wouldn’t stretch to a convincing robotic prosthetic. Rogersz is searching for whatever Parnell has stolen and decides to utilise the network of rival repossession companies to help retrieve the Chevy Malibu, which is leaving a trail of bodies in its wake. This sets in motion a sequence of bizarre and often surreal events, ultimately dragging Otto toward his unexpected destiny.

Repo Man is a radical film that broke new ground in terms of style and storytelling, utilising a multi-stranded, fractured narrative. However, it follows a well-established fairytale template, involving a protagonist leaving home and entering a “magical kingdom” where they grow through interaction with a series of mentors and facilitators, overcoming adversity and realizing their inner potential. The glowing MacGuffin in the trunk of the ’64 Chevy serves as a stand-in for Excalibur—the transformative item that only those deemed worthy may wield, or in this case, take for a joyride without being vaporised. Otto is presented as the protagonist, but he’s by no means a traditional hero. He’s instead a cypher who’s yet to find his personality and is only ever reactionary until the very last moments of the movie.

For a film that may seem to be a simple satire, it has incredible complexity ‘under the hood’, or perhaps that should be in the trunk? True, it does seem like a wish list of happenings and snippets of dialogue that a few mates might come up with, Beavis & Butthead-style, over beers… and perhaps some shoplifted sushi. And that’s how it’s meant to be received, the script disdains seriousness and whenever its hefty subtext threatens to break the surface, it’s beaten back by energetic flippancy— a pause and a resounding “fuck that.” Or, when a pretentious punk lies face down in a pool of his own blood after a botched armed robbery, decrying with his final breath the society that had formed him and prescribed his life of crime, his argument is succinctly shot down by Otto in an attempt to lend clarity to those final moments, along with the kind lie that he’ll be okay.

The unpredictable climax was realised with beautifully dated SFX by Roger George. George’s career began with an impressive array of 1960s B-movies and exploitation films. He notably provided trippy visuals for the psychedelic sequences in Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967) and the joyously awful Deathsport (1978). However, George was also on the team working on the groundbreaking animatronics for Joe Dante’s The Howling (1981). Around the time of Repo Man, he was also working on James Cameron’s The Terminator (1984).

Repo Man was released without fanfare and barely elicited a critical response. Initially, it earned only $95,300 towards its final budget of $1.5M, and it was prematurely pulled from a very limited theatrical run. It was almost consigned to languish in the Universal vaults as collateral, but sales of the rousing soundtrack soared unexpectedly, generating significant publicity. When re-released about six months later, it found a receptive cult audience, packing out arthouse and indie cinemas, and garnered mostly positive reviews, winning the Boston Society of Film Critics Award for ‘Best Screenplay’. Tracey Walter also took the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films Saturn Award for ‘Best Supporting Actor’. It quickly gained enough notoriety to capitalize on the burgeoning home video market, which was growing faster than demand could be met, and distributors were eager for this type of offbeat cult content. Ultimately, Repo Man recouped around $4M and established Alex Cox as a young director with the potential to get ahead of the zeitgeist.

His follow-up was the biopic Sid and Nancy (1986), which was critically acclaimed, though not a blockbuster, and appears to be the peak of his career. Most films that followed have failed to secure mainstream distribution due to either production problems and resulting delays or their politically charged content, as is the case with Walker (1987), which Cox still considers his best film.

USA | 1984 | 92 MINUTES | 1.85:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writer & director: Alex Cox.

starring: Harry Dean Stanton, Emilio Estevez, Tracey Walter, Olivia Barash, Sy Richardson, Vonetta McGee, Richard Foronjy, Susan Barnes, Fox Harris & Tom Finnegan.