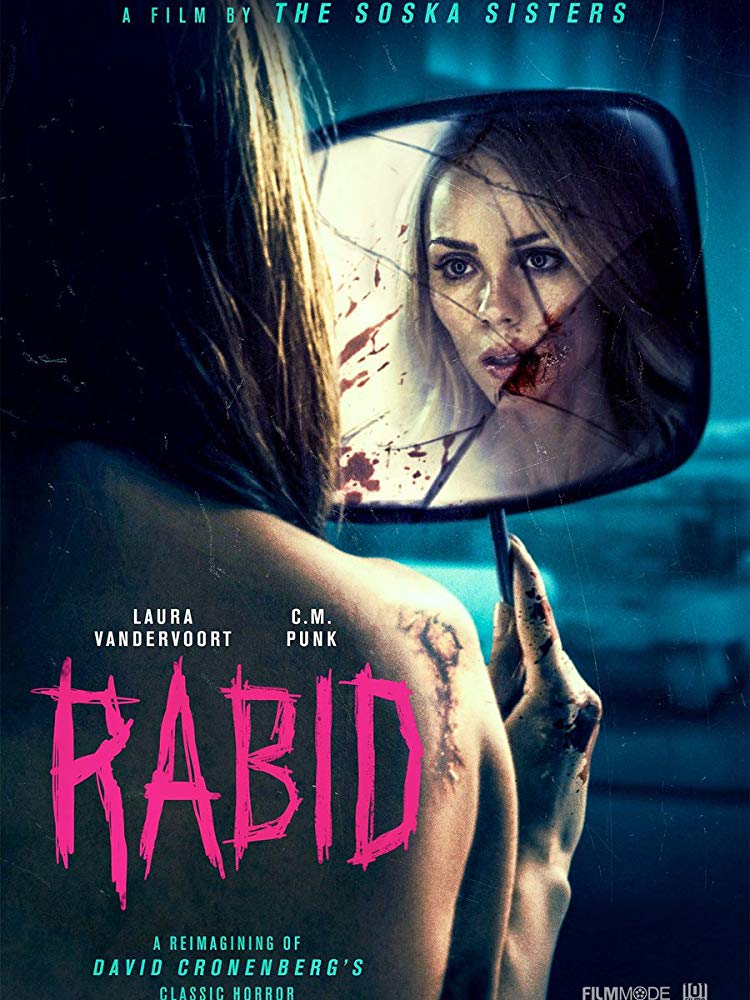

RABID (2019)

A beautiful fashion designer is left horribly disfigured in an accident and seeks out an experimental treatment with unexpected side effects...

A beautiful fashion designer is left horribly disfigured in an accident and seeks out an experimental treatment with unexpected side effects...

David Cronenberg finds the term ‘Cronenbergian’ strange. When referencing his influence, people tend to fixate on Videodrome (1983) or The Fly (1986), but his work’s spanned many genres outside horror. Is Maps to the Stars (2014) or A History of Violence (2005) horror? Cronenberg is an individual fascinated by the fragility of the human form. Between Rabid (1977) and The Brood (1979), he did a movie about race-cars, Fast Company (1979). As his later Crash (1996) would delve into, vehicular accidents are an everyday source of bodily annihilation.

Only his second feature, Rabid featured many of these themes. Crash survivor Rose undergoes experimental surgery which mutates into an insatiable hunger that spreads like rabies to her victims. Jen and Sylvia Soska are twin directors who play with similar concepts. Their film American Mary (2012) dealt with surgical obsession and consensual mutilation, being just short of a Cronenberg fever dream itself, and now they further mutate his original concept for Rabid with a fresh female perspective.

One notable distinction in Cronenberg’s filmography is the female lead of Rabid, although his other films do feature strong independent women (Geena Davis, Debbie Harry, Marilyn Chambers) giving standout performances. Cronenberg may be commentating on how the male pursues self-destruction but his female roles actively engage the same psychosexual behaviour. The Soska Sisters tone down the overt perverseness in his direction but still craft a psychological and physical transformation for Rose (Laura Vandervoort) to explore.

The Soska’s version of Rabid expands on almost all aspects of the original and builds a story where one wasn’t before. Little’s known about Cronenberg’s Rose as we’re introduced to her mid-crash and only start following her as she spreads her new disease. This new Rose has a life. A profession in the fashion industry that provides personal ambition along with friends and love interests that deliver human interactions. While the original is shocking and intriguing for the core horror concept, it’s told in a shallow world where we never get to know anyone well. Rose has an actual life to risk losing now. The fashion element weaves into the rest of the film both structurally and thematically. The fleshed-out protagonist provides a much fuller sense of narrative while the original was too clinical for me to get invested in.

Instead of an Easy Rider (1969) biker, Rose now rides a trendy modern scooter. But she doesn’t crash yet. We’re allowed to become familiar with her stunted potential in life before the life-changing incident. Avoiding the obvious trope of a social outcast, she actually has a pretty decent place in a life she wants. The fashion industry is a cutthroat world and yet it’s her underlying self-doubt that holds her back, not her physical imperfections. At one point, her colleague and suitor Brad assumes this is a temporary diversion from what she really wants. These moments steer the horror toward a more significant social commentary. Misunderstanding a woman’s hunger toward self-empowerment as something strange and alien.

The female perspective shines many times, especially in the small details. Rose has suffered a crash already, as many women have endured traumas throughout their lives, which debilitates her emotionally more than physically. Facial scars haven’t rendered her monstrous but it’s destroyed her self-esteem. The damage done in the original was arbitrary, but here the violence targets the female face—the supposed source of a woman’s worth. Even in the lead-up to the second crash, it’s left debatable on fault. Was it the company she surrounds herself with pushing her into racing off, or her lack of confidence driving her away?

Like how ‘Cronenbergian’ goes deeper than genre, the real horror of Rabid starts here. The crash leaves her face a visceral wound; her jaw destroyed and reconstructed, and teeth so misplaced they protrude out of the gore that’s left of her cheek. There’s no science-fiction but body disfigurements are a form of horror these films succeed in. People make the common mistake in questioning the significance of women in horror and answer with simple misogyny. That may only be true in certain cases. A more enriching understanding is that so many women live through an internalised horror story and cinema is a gateway to externalising that. Not only are Rose’s gnawing issues exposed for all to see but she can’t even speak through this new horror. The real body-horror lies in her reduction to a physical freak with no form of expression, that is until her passion for fashion becomes her voice.

Looking for the solution to all her problems, Rose finds a private clinic that promises cosmetic miracles with no fees other than being an example of their success. Not only is her recent disfigurement undone but even the faint scars that have haunted her since the start of the film are gone as well. She’s more beautiful than ever and yet the Soska’s emphasise that her newfound confidence is the catalyst for her new lease on life. Brad liked her before the crash, her boss was more captivated by the self-designed dress she wears, and she maintains the position she wants rather than become a model because now she’s gorgeous. The extremes society pushes women to becomes immediate. The doctor warns her of potential side-effects stemming from a new liquid food diet and unknown medication. Just as her external horror is fixed it becomes an internal struggle again.

Keeping to her new regiment proves fruitless as hallucinations and intense cramping pains start to plague her. Most disturbing are her trance-like ventures toward unsuspecting men like the fellow clinic patient or exceptionally sleazy clubber (played by ex-wrestler CM Punk) which end with her biting them. Not eating them nor even killing but the transference of fluids between strangers still evokes a real fear. An uncomfortable crossing of mythology and reality with that of vampires and the AIDs crisis.

These unconscious encounters seem a different world than the one Rose is living. At her job, her personal works are so impressive that her dress is now the big finish at the upcoming fashion gala. Brad has managed to break through her past barriers and the two are starting to fall for each other. A quaint restaurant brunch is ruined when one of her earlier victims literally smashes into the scene in one of the film’s most effective scares. A confident woman sending men insane becomes literal as she’s driven to spread a virulent form of rabies that turns people into destructive feral carriers. Rather than devolve into a zombie-like outbreak, the Soska’s with co-writer John Serge find space for social commentary. These plagues and misfortunes only affect the common people as the elite are too self-absorbed to see how it might infect their society.

In one rather harsh negative criticism, it becomes apparent how low-budget this is when attempting the chaotic finale at the gala. Aside from a distracting CGI billboard at the start, the film follows a personal narrative that allows for tight, contained storytelling. But when the climax includes armed police and the only visual inclusion is a glaringly obvious stock-footage insert of a gun there must be creative alternatives. Thankfully, the film then properly ends after that with the biggest practical effect that captures the grotesque attractions Cronenberg is most famous for.

The core tenant of Cronenbergian can be found when Rose defends her wanting to be in the fashion industry, “it’s like armour, when you walk out the door you’re arming yourself.” The horror lies not only the fragility of our own bodies but when the physical bypass our mental strength, that through human interference our biology can adapt and evolve beyond what we’re comfortable with. People tell us the world is a harsh and indifferent place and we need to toughen up if we want to survive, but this breeds mutation that can turn us into monsters.

directors: Jen Soska & Sylvia Soska.

writers: Jen Soska, Sylvia Soska & John Serge (based on ‘Rabid’ by David Cronenberg).

starring: Laura Vandervoort, Ben Hollingsworth & Phil Brooks.