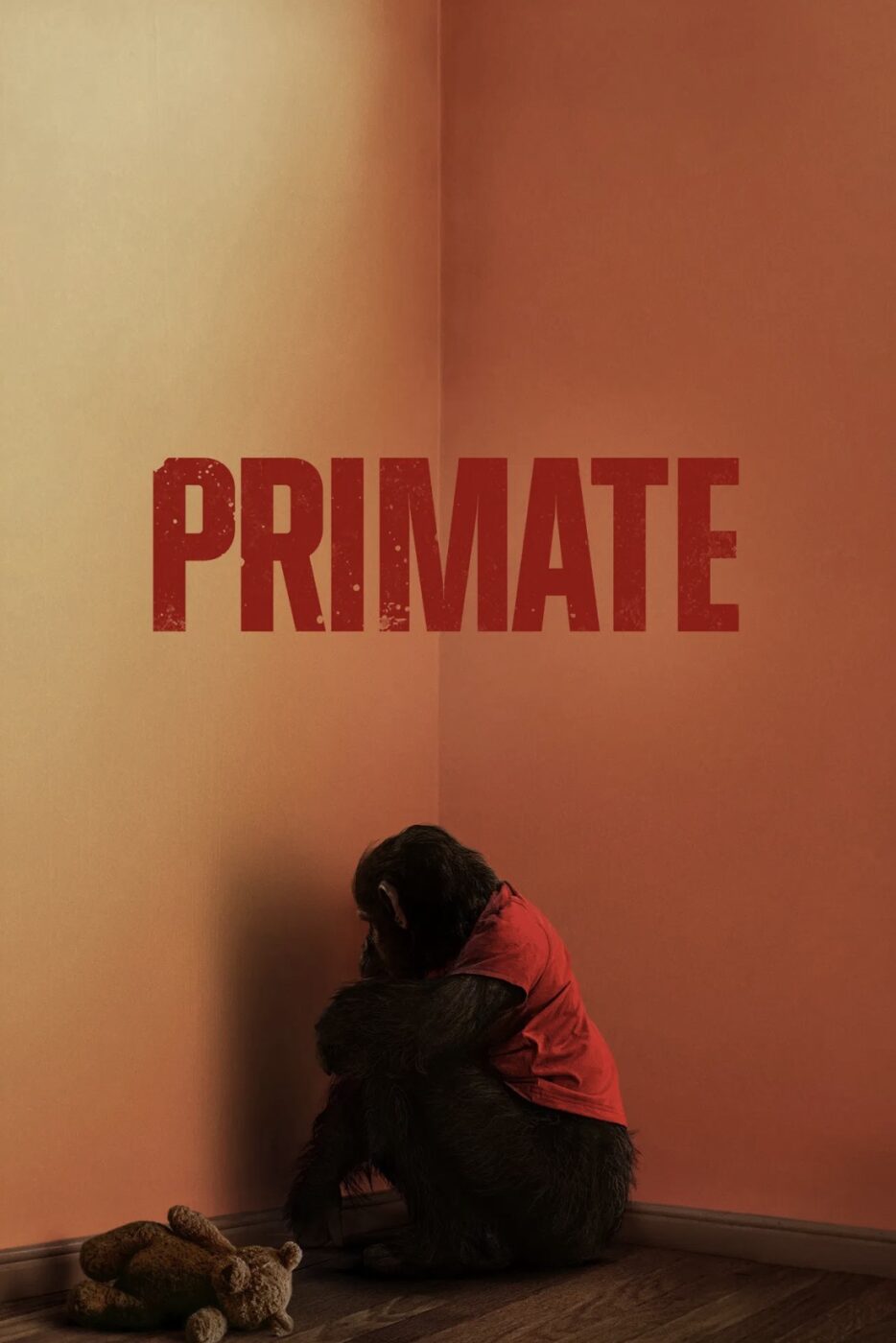

PRIMATE (2025)

A group of friends' tropical vacation turns into a terrifying, primal tale of horror and survival.

A group of friends' tropical vacation turns into a terrifying, primal tale of horror and survival.

English director Johannes Roberts clearly has a penchant for predatory animals. Having previously helmed the efficient, if somewhat forgettable, shark features 47 Meters Down (2017) and its sequel, Uncaged (2019), he’s now turned his attention to a “monkey-gone-mad” tale with his superior new film, Primate. This latest creature feature doesn’t waste any time establishing its credentials; within the opening minutes, we witness a vet attempting to treat a clearly unhinged chimpanzee named Ben. Let’s just say the vet won’t be making any more house calls.

What makes this opening especially effective is that Roberts doesn’t present Ben as some one-note snarling monster. There are brief, unsettling flashes of recognition in his eyes : confusion, pain, even fear , that suggest an animal still fighting against what’s happening to him. These tiny moments of vulnerability not only make you feel some level of sympathy for Ben, they act as a clever device to build on the suspense (also used later on); leaving you with a constant feeling of doubt as to how the infected monkey is going to behave.

The film then jumps back 36 hours to meet Lucy (Johnny Sequoyah), a university student returning home to Hawaii. Joining her are her best friend Kate (Victoria Wyant) and Kate’s pal Hannah (Jessica Alexander). Upon arriving at Lucy’s stunning cliffside residence, she reunites with her deaf novelist father Adam (Troy Kotsur), her resentful younger sister Erin (Gia Hunter), Kate’s brother Nick (Benjamin Cheng), and Ben. An unusually intelligent pet, Ben communicates via a tablet developed by Lucy’s late mother, a linguistics professor. Roberts smartly uses these early scenes to establish Ben as part of the family unit rather than an exotic curiosity. He plays word games, mimics gestures, and reacts with childlike irritation when ignored.

Shortly after their arrival, the teenagers learn that Adam must leave for a night as he has to go to a book-signing event. Naturally, they decide to throw a party in his absence. What they don’t know is that Ben has been bitten by a rabid mongoose. Before you can say “bananas”, the once-friendly Ben has turned “batshit-crazy”, trading word games for a violent rampage. Cue a barrage of jump scares, dismemberment, and gore; in case there was any doubt, the ensuing carnage easily earns the film its 18 certificate.

The gore itself is refreshingly tactile. Limbs are twisted and chewed, jaws snap with bone-crunching force, and blood sprays in thick, sticky sheets rather than digital mist. Roberts favours practical effects wherever possible, and it shows. While the viscera on display is shocking at times, the filmmaker doesn’t linger on the carnage, he’s more interested in giving you a scary sequence rather than cheap gross-out moments.

Alongside the just-about-believable concept of a primate raised in a domestic setting (reminiscent of the documentary Project Nim), the film works because it doesn’t take itself too seriously. It isn’t chasing Academy Awards or trying to be a “prestige” thriller. At its heart, it’s a B-movie horror executed with impressive precision—running at a tight 89 minutes.

One of the film’s smartest creative choices is the way the script weaponises the setting. Early on, it is explained that a rabid animal will recoil at the sight of water. Knowing Ben can’t swim, the teenagers flee to the house’s infinity pool, which happens to be perched on a cliff’s edge. It’s a clever plan but a precarious location. Without spoiling the outcome, the script exploits this setup for all it’s worth. Indeed, the entire open-plan design of the house is beautifully utilised to wring out every drop of tension and mayhem.

Another standout set-piece occurs when one of the girls becomes trapped inside a car in the driveway. What should be a safe haven turns into a nightmare when Ben reveals a horrifying level of problem-solving intelligence, calmly using the remote key fob to lock and unlock the doors at will. The scene plays out like a sadistic game, with Ben’s earlier “playful” interactions now twisted into something cruel and calculating. It’s one of the film’s most inventive moments, proving that Ben isn’t just about brute force—he also possesses a level of simian intelligence that makes him even more disturbing.

The performances are better than one might expect from the genre. While the cast is stereotypically attractive, they’re convincing when it counts. Johnny Sequoyah is excellent as Lucy, displaying an impressive emotional range that shifts from caring sister to terrified survivor. Troy Kotsur (CODA) may only have a minor role, but he brings a level of authenticity and empathy that grounds the drama.

Then, there is Ben. In past films like Richard Franklin’s Link (1986) or the abysmal Congo (1995), primate effects relied on shaky CGI or real animals prompted by off-screen handlers. Here, the “monster” is a mostly practical triumph. Movement specialist Miguel Torres Umba wears a custom suit designed by a team of 50 artists, supplemented by animatronic heads to convey Ben’s shifting emotional states, all nicely topped off with some hi-tech mo-cap. The end result is truly terrifying.

Director Roberts also deserves credit for not relying solely on graphic kills. The sound design is exceptionally clever: a mobile phone ringing when a character is trying to hide, or the chilling sound of Ben alerting the group to his presence via his communication tablet. A late scene involving the father’s return is particularly effective, plunging the audience into his silent perspective while the monkey wreaks havoc just out of sight.

Ultimately, Primate is a slasher movie that swaps Michael Myers for a chimpanzee. Roberts leans into this with several nods to the genre: a phone-based narrative device reminiscent of Scream (1996), and a scene involving a slatted wardrobe door that is a direct homage to Halloween (1978). There’s even a dash of Jurassic Park (1993), yet it’s all executed with such gusto that these “inspirations” never feel derivative.

Top marks go to the technical team as well. Composer Adrian Johnston provides a brooding, synth-heavy score with definite echoes of John Carpenter. Meanwhile, Stephen Miller’s cinematography expertly balances light and shadow, using framing to keep the audience wondering exactly where Ben is hiding. It creates a genuine sense of foreboding.

“Crazy monkey” movies are rare; the last one I truly enjoyed was George A. Romero’s Monkey Shines (1988). For my money, though, Primate is the stronger film by some margin: it’s lean, mean, and wonderfully entertaining. Where Romero’s film becomes bogged down in subplots and sentimentality, Roberts keeps his focus razor-sharp, allowing character beats to serve the suspense rather than derail it. Primate understands that less is more : fewer ideas, executed better, with far more blood.

USA • UK • CANADA • AUSTRALIA | 2025 | 89 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Johannes Roberts.

writers: Johannes Roberts & Ernest Riera.

starring: Johnny Sequoyah, Jessica Alexander, Victoria Wyant, Gia Hunter, Benjamin Cheng & Troy Kotsur.