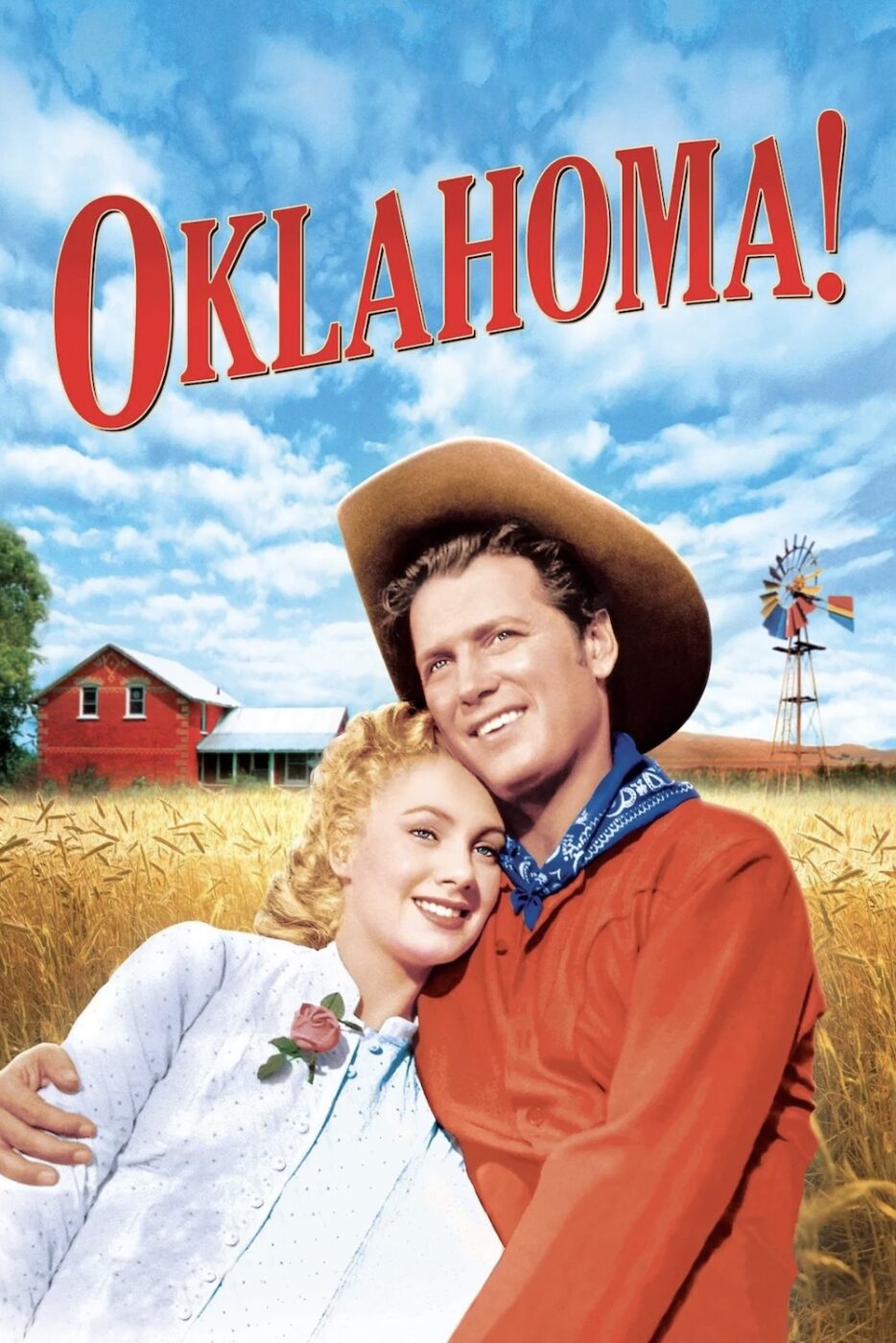

OKLAHOMA! (1955)

In Oklahoma, several farmers, cowboys and a traveling salesman compete for the romantic favors of various local ladies.

In Oklahoma, several farmers, cowboys and a traveling salesman compete for the romantic favors of various local ladies.

My introduction to the 1955 film Oklahoma! came in the 1990s via a VHS tape. I was only five years old and in elementary school at the time. While I didn’t understand everything on the screen (like what it was that Ado Annie couldn’t “say no” to and why anyone would want to look at women on playing cards), I did fall in love with it. It was, in part, the cinematography that made the simple western US landscape feel huge, like a fairy tale world, and, in part, the soaring music provided by Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein.

What I could not know at that tender young age was that the cinematography was epic, in large part thanks to a new technique that was tested for the first time on this film, and that Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein insisted on having final creative say in any changes, including cut songs, lyric enhancements, and any song additions (thankfully, there were none). In other words, what made Oklahoma! a delight to the eye and the ear made it a nightmare to film and produce.

The plot of Oklahoma! seems deceptively simple. A young cowhand, Curly (Gordon MacRae), has his eye on a pretty farm girl, Laurey (Shirley Jones). Complications arise when he realises that she’s also being courted by her troubled farm hand, Jud Fry (Rod Steiger). There are some other subplots involving another cowhand, Will Parker (Gene Nelson), and his troubles with his flirtatious fiancée, Ado Annie (Gloria Grahame).

The late-1940s and early-1950s were not just the golden age of Hollywood; they were a golden age for Broadway. That all started with Oklahoma! First produced on Broadway in 1943, Oklahoma! is considered by many to be the first truly modern American musical. Before Oklahoma!, scripts had simple, often funny but usually ridiculous plots that were nothing more than vehicles to help move us from one grand musical number to the next. The songs revealed less about the characters we were seeing on stage and more about how witty and clever the lyricists and composers could be. When there was a full 10-15-minute ballet/dance break in the middle of the show, it often had nothing to do with anything that had happened onstage previously.

In other words, musicals were shallow amusements not meant to be taken seriously in any way. That changed when the president of the struggling Musical Theater Performer’s Guild approached Richard Rodgers with the idea to adapt a straight, dramatic play, Green Grow the Lilacs, into a musical.

Richard Rodgers, who was, by then, a well-known composer thanks to shows and songs he had written with lyricist Lorenz Hart, loved the idea and approached Oscar Hammerstein to write both the lyrics and the book (script). Oklahoma! went on to become the biggest ticket on Broadway.

When Magna Theater Corporation bought the film rights ten years after the Broadway première, Oscar Hammerstein and Richard Rodgers were apprehensive. And, if you look at the musical film adaptations of Broadway shows in the 1940s and ‘50s, it’s easy to see why.

When you watch other musicals from the era like On the Town (1949) and Kiss Me Kate (1953), it’s clear that they vary significantly from their stage counterparts, and the changes from stage to film weren’t made for the better. Back then, when a film studio gained rights to a musical, it was understood that the film studio and the director had complete and total freedom. That freedom often included adding new songs by completely different composers, cutting songs and entire plot lines at will, and even changing out old characters for new ones.

As a result, the film versions of musicals often bear little if any resemblance to their stage counterparts. Hammerstein in particular was not interested in having his book rewritten and Richard Rodgers, who had past bad experiences with this trend, did not like the idea of seeing yet another composer write new songs for his show.

That, perhaps, is why Oklahoma! remains to this day one of the most faithful stage-to-film adaptations of any musical. There are no unnecessary changes to any of the songs, no new songs and only two songs that were cut—“Lonely Room”, originally sung by Jud Fry and “It’s a Scandal, It’s an Outrage” sung by Ali Hakim (Eddie Albert) and the male chorus. All of these changes were entirely needed.

“Lonely Room”, sung by Jud when he realises that he has real competition for Laurey’s affection, is filled with longing, bitterness and obsession. The thing is, in the film, we don’t need to hear about those feelings in a song. Rod Steiger embodies these feelings in his entire performance.

Every sentence he speaks is dripping with bitterness that is underscored by an almost sympathetic longing that is tempered by clear and frightening obsession. If the role of the villain in this film had been taken up by a lesser actor, Jud’s solo might have been necessary. Steiger makes it superfluous.

Something similar happens with “It’s a Scandal, It’s an Outrage” which, in the stage show, is sung by Ali Hakim after he’s forced to propose to Ado Annie, the farmer’s daughter he’d been innocently flirting with, at the barrel of her father’s gun.

The song was initially cut because Albert was uncomfortable leading an entire song, even though he would be helped by the male chorus. However, it was already probably the weakest song in the show, and the scene between Ado Annie, her father (James Whitmore), and Hakim had already made the salient point perfectly clear. And, like with Jud, Albert’s on-point comic facial expressions and line delivery already make the forced nature of the proposal funny enough. We don’t need a musical number to sell it.

The only other major change comes in terms of the scene locations. Oklahoma! was known, at the time, for having the longest single scene in Broadway history. In the stage version, we stay in one location, with no set changes, for the first 45 minutes of the show. Of course, in cinema, that would get very, very, dull. Not to mention, the director, Fred Zinnemann, was working with a new widescreen process that was meant to enhance and bring natural vitality to filmed locales. In order to put that process to use, there had to be a few lush locations to see.

At the time, this system, then called TODD-AO, an early version of the single-camera process very familiar to film today, was so new that the director and crew decided to film two versions of Oklahoma! One with the more familiar CinemaScope that would be distributed by another studio (RKO Pictures) and a second shot in the specially created single-camera widescreen.

Luckily, the new process worked beautifully. The vivid colour of the corn stalks in the opening shot and the natural movement of winds on the plain and clouds in the sky perfectly accompany the iconic opening notes of the film’s first song, “Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’.” These are the images I remember being entranced by even as a young child. Seventy years after the film’s release and over twenty years since my first viewing, the imagery from the lush lakeside setting of “I Can’t Say No” to the dramatic hay stack burning that accompanies Jud and Curly’s ultimate show down is every bit as beautiful as I remember.

The music also remains mesmerising. Shirley Jones and Gordon Macrae both have a full-throated, operatic sound that has largely passed out of musical theatre save for the occasional Disney musical or niche production. When it comes to songs of this era, the disappearance of classical voice styles is a shame. The more common light and bright sounding baritone/tenors of today, however good, never really do justice to songs like “Oh What a Beautiful Mornin’” and Laurey’s “Many a New Day” doesn’t hit as well without the perfectly measured vibrato soprano of Shirley Jones. Indeed, there’s little to be said against the music or voices in this production.

Most of the modern criticism of this particular film centres around two things: the plot and the acting. Both of these, I will concede with two reservations, are very much a product of their time. It’s clear that both Shirley Jones and Gordon Macrae got their performance experience from the stage, and in the era before method was in vogue, their over-the-top movements, expressions and gestures would read very well from a balcony seat in a theatre but often feel forced and awkward when seen close up on camera. Most of the main cast comes from a similar background and so deals with the same issues. The lone stand out is my first reservation: Rod Steiger.

I’ve sung his praises before in this review but it bears repeating. There’s an authentic quality to everything he does in this film that shines more brightly and more sinisterly, perhaps, because of the rest of the cast’s lack of authenticity. When the villain is the only one who is playing it straight in a cast of clowns, it makes him more frightening.

The plot has been described as ‘formulaic’ by some ill-advised modern critics. What they fail to realise is that this musical created the formula. It was the pioneer of its day and not a factory replication. So save your formula criticisms for movie musicals that truly deserve the title. But, beyond the formulaic criticism, there are some genuine issues brought up regarding female agency, mental health and sexual politics that deserve some digging into.

First, let’s get this out of the way. I hate the famous exchange in both the show and the film which suggests that the only time a woman doesn’t need a man is when she’s dead. That said, lines like this and plots about Ado Annie’s flirting and whether Laurey takes Curly or Jud to the dance have to be examined within the context that they were written.

Oklahoma! has two strikes against it for modern audiences. It was written in the 1940s when women were still struggling for equality and mentally ill people were still tucked neatly away in asylums. It was also written about an even earlier time (the early 20th-century) when women had even less agency, courting rules were well established, and mental illness carried a taboo not only against the individual with it but against their family and associates.

The issue with mental illness, suggested by some to be part of Jud Fry’s character, is the second reservation for me. And this comes from personal experience. When I became a teenager and decided it was cool and grown-up to criticise the films and musicals I loved as a child, I joined a chorus of girls in my high school who believed that Laurey’s acceptance of Jud’s invitation to a party constituted her ‘playing with his emotions’. We all agreed that, if she was that scared of him, she should have simply turned him down and gone to the party alone.

What we didn’t take into account is, in a small community in the very early 1900s, it would have been more than a bit of a scandal if a girl went to a party unaccompanied by a man. That’s the historical framework that modern feminists miss. But aside from that, there may be a deeper reason that Laurey felt compelled to accept Jud’s invitation. That’s the part that I’ve had personal experience with.

I was 16 and a sophomore in high school when a boy slipped a note into one of my books saying that I was beautiful and he was in love with me. I wasn’t interested and, gently, told him I just wanted to be friends. Despite this, he kept hounding me, crossing my boundaries, even getting some of my friends on his side. In the end, he assaulted me. I didn’t tell anyone about it until two years later.

Why didn’t I speak up? I was scared. He was bigger than me. Stronger than me. And, he’d made me feel as though his obsession with me was somehow my fault. Now, when I look at Oklahoma!, everything about Laurey and Jud’s interactions remind me of that boy.

The one scene where the two of them are alone together is, by far, Shirley Jones’ best acting performance in the film. The way she looks sideways at Jud as he sidles closer to her, the way her body stiffens and the stilted way she speaks, as though she’s trying desperately to keep herself in check, even when she’s terrified, is palpable. While this could be because Steiger’s obsessive longing is played so well, it could also be because this is a situation that Jones, as a young, attractive woman in the entertainment world, had been in before.

The truth is, even now in our uber-feminist world, sometimes we can’t just say no to men who aggressively pursue us. Sometimes we fawn or freeze or flee (as Laurey eventually does). While the ending of this particular film sees Laurey rescued by a male knight in shining armour (another product of his time), maybe modern audiences can still learn something from this. Maybe, women and girls can see Curly’s character as a metaphor for their inner strength and power, at least when it comes to his final conflict with Jud. Maybe we can take inspiration to take that memory of that obsessive boy and wrestle it until the memory falls on its own knife, thereby freeing us.

When looked at from that lens, aside from some 1950s acting styles and plot lines that make many modern audiences groan, there’s little to complain about in Oklahoma! and a lot to praise. That is, perhaps, why it has remained a cinematic treasure for seven decades and will likely remain so for seven decades more.

USA | 1955 | 145 MINUTES | 2.20:1 (70mm) • 2.55:1 (35mm) | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: Fred Zinnemann.

writers: Sonya Levien & William Ludwig (based on the 1943 musical stage play by Rodgers & Hammerstein, itself based on the 1931 play ‘Green Grow the Lilacs’ by Lynn Riggs).

starring: Gordon MacRae, Gloria Grahame, Gene Nelson, Charlotte Greenwood, Eddie Albert, James Whitmore, Rod Steiger & Shirley Jones.