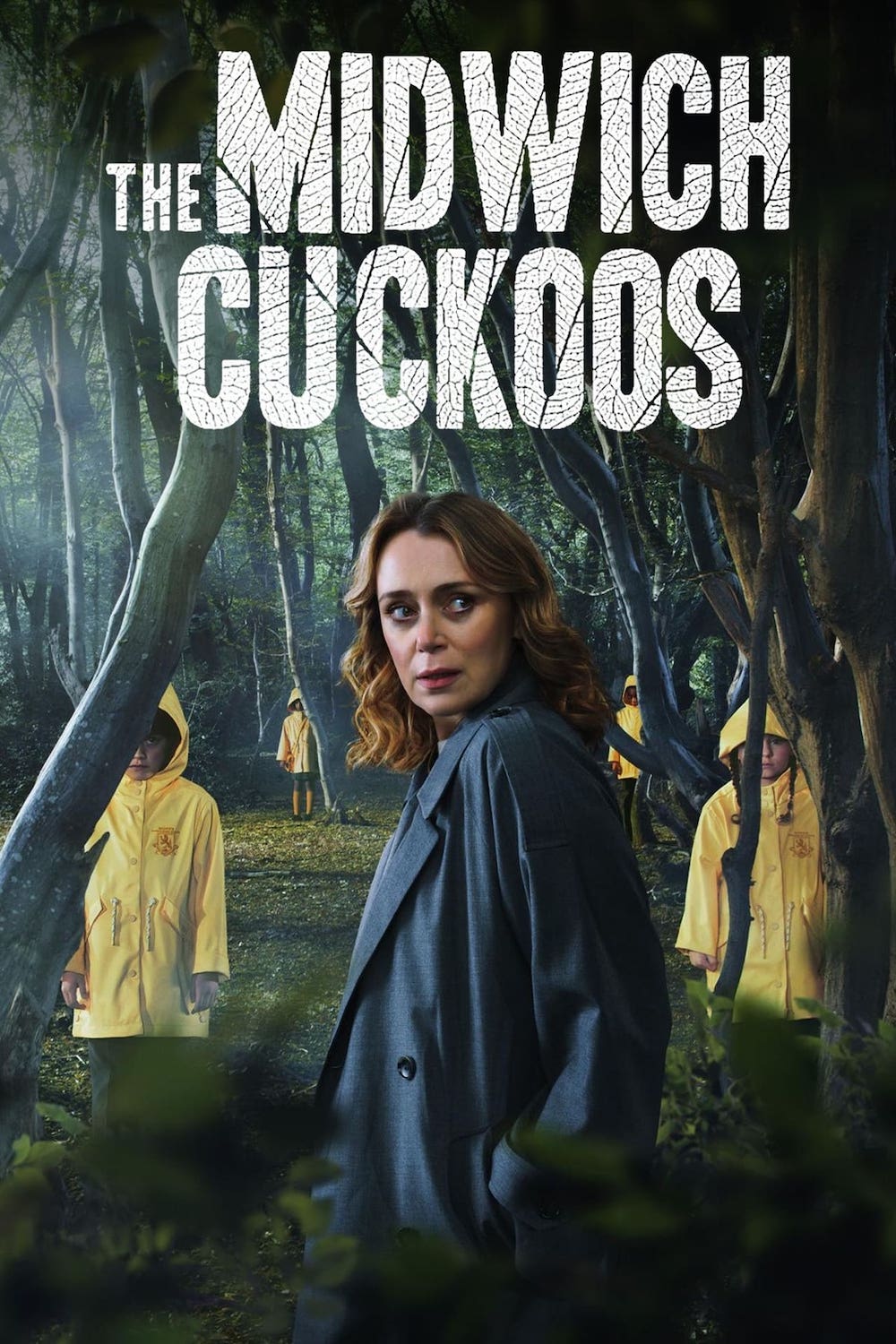

THE MIDWICH CUCKOOS

An inexplicable incident in a small English town is soon followed by the birth of mysteriously powerful children.

An inexplicable incident in a small English town is soon followed by the birth of mysteriously powerful children.

John Wyndham’s 1957 novel, The Midwich Cuckoos, has been adapted for the cinema twice—as the unnerving Village of the Damned (1960), then John Carpenter’s less esteemed 1995 movie of the same name—as well as making its influence felt in many other tales of children with unusual powers, not least of all Eskil Vogt’s superb The Innocents (2021). But it’s a relatively short novel and both films clocked in at under 100-minutes, so one of the challenges facing series creator David Farr in adapting The Midwich Cuckoos must have been how to fill almost six hours of television.

To achieve this he places ar more emphasis on the adult characters than Village of the Damned did, although not always with huge success. A great deal of screen time is given to people who aren’t very interesting, or at least not allowed to reveal enough of themselves to become interesting. In particular, Zoë (Aisling Loftus) and Sam (Ukweli Roach), with whom the series begins and in which it emphasises, are the kind of nice-but-dull couple you’d be happy to live next door to but wouldn’t want to go on holiday with.

Many of the other developments made by Farr and his writers to the novel (and 1960 film) are well-handled. Some are necessitated by updating the story to the present day (the presence of DNA testing, counselling, social media, CCTV) and adding modern interest, others (the way unmarried motherhood isn’t an issue) are unproblematic, and some (the way a modern English market town is dominated by people who’ve moved from elsewhere) are quietly witty.

There is, however, one other major change—beyond the bland characters—that tends to dilute the uncanniness of The Midwich Cuckoos. Midwich itself, a village in the original, here becomes a town of 11,000 people–with a police station and hospital that’ll seem hilariously large to anyone who’s visited many such places in the UK, though perhaps the population of Amersham in Buckinghamshire (where most of it was filmed) are just lucky in that respect?

This means that instead of the incident that opens the story affecting the whole community, it only involves a small area and subset of people. While in the earlier versions of The Midwich Cuckoos the strange children who result from that incident dominate the whole place, here it’s easy to see they’re just an anomaly in an otherwise ordinary world, which makes them seem more containable and less threatening.

Of course, fidelity to the 60-year-old source material isn’t the be-all-and-end-all, and viewers who don’t know previous versions will be forgiven for not caring much. But some of these changes exemplify how The Midwich Cuckoos, despite such strong models to build on, never quite manages to rise above the humdrum.

The seven episodes begin with Sam and Zoë preparing to flee the town, with unexplained soldiers in the background, their daughter Hannah present and striking the viewer as a peculiar girl, though it’s too early to say quite why. Quickly, however, the show rewinds to five years earlier, with the couple arriving in Midwich; a newspaper clipping on the estate agent’s wall identifies the town as a great place to bring up kids. This first episode also introduces Susannah Zellaby (Keeley Hawes), who has the closest thing to a lead role in the ensemble cast, as well as the prep school where Sam teaches and where much important action takes place.

Things get off to a slow start—a few flickering lights (later a recurrent motif) are the only indication that something might be amiss—but patience is eventually rewarded with an effective sequence where everyone in the area around the school falls suddenly unconscious, and so do the emergency service workers in hazmat suits trying to rescue them. Horses running wild through the street add an almost magical touch, while a shot of a lawnmower going round and round in circles is one of the few direct visual echoes from the 1960 film.

That shot will itself be echoed at the beginning of the next episode with an overhead view of a horse walking in a circle. But from this point on there’s not much time for elegant photography (despite one powerful later image of children lined up, silhouetted, in the woods), because after its sluggish introduction The Midwich Cuckoos picks up the pace and plot developments come more regularly.

It soon becomes apparent that all the women caught in the episode have mysteriously become pregnant. There’s talk of terrorism and national security, the Official Secrets Act is invoked, and an old paper file in Cyrillic script is glimpsed. All the children are born simultaneously; in one of the series’ best scenes three of the “blackout mums” decide at the same moment not to terminate their pregnancies, moments before signing the consent forms. The children, once born, grow too big too quickly. A baby somehow stops its mother from getting on a train to leave the town.

And so, even if the bulging and pulsating abdomens of the women are a little OTT, there’s plenty of just-plausible-enough inexplicability to whet the appetite by the end of episode 2. Come episode 3, a further couple of years have passed and the children are now firmly established in the town, as well as subjects of study at a special ward set up in that large hospital. Another of the best scenes in The Midwich Cuckoos depicts them choosing pictures on individual screens, as a test for ESP. That they have more than just psychic ability, but a kind of collective hive mind, will come as no surprise to anyone familiar with the originals. When Zoë asks her daughter (about another of the blackout children) “how do you know that girl?”, the eerie reply is “we’ve always known her.”

The Midwich Cuckoos finally moves forward another two years in episode 6—perhaps the best single episode, with a major new question and several surprises, as well as a significant scene where the children are listening to a history lesson on the subject of conquest. (“You can’t stop it, it’s too late,” says one of them in another, but very clearly related context.)

All is explained, eventually. Well, everything except the biggest question of all, and explaining that in full would undoubtedly weaken the impact of the story—for as soon as we know exactly what the children are, we’d know the limits of their power. Yet while The Midwich Cuckoos does a decent job with its sci-fi and thriller elements, the unengaging characters keep dragging it down.

At least the child psychologist Susannah Zellaby (who shares her surname with a Wyndham character) has some depth. Her position as someone with access to the government-sponsored scientific studies of the children without being fully part of the establishment makes her a useful proxy for audiences, and she believes that despite their apparently communal behaviour the children can be individual. Susannah’s quest to prove this provides a personal struggle to contrast with the bigger issues of humanity versus the non-human. Or differently human, perhaps. It’s Susannah’s daughter Cassie (Synnøve Karlsen) who argues the children might be mankind’s next evolutionary step—the same point having been made by the Zellaby character in Village of the Damned.

Both Karlsen and Hawes (as Zellaby) give convincing performances, as do Max Beesley as a local senior police officer and Lewis Reeves as a father who can’t bring himself to love his—or, more pertinently, his wife’s—blackout son. Samuel West doesn’t ring true and certainly doesn’t seem trustworthy as a civil servant sent to Midwich to oversee the government’s response to the children’s arrival… but eventually, we learn exactly why he shouldn’t ring true and there’s a touch of unexpected tragedy here. Among the children (who here, unlike in the novel and movies, don’t look identical), Adiel Magaji is most memorable as the older version of Nathan, a boy who seems to confirm Susannah’s ideas by rebelling against the others.

Sky’s Midwich Cuckoos is far from completely lacking in interest and watchability, but the strengths of the storyline—around the children themselves, the investigation into their nature, and the question of what to do with them—are weakened by the insipid adults surrounding them. It’s possible that Farr and his writers intended to use The Midwich Cuckoos to explore modern parenthood (the mothers give up work, stop seeing friends, don’t leave town, and so on), and Wyndham’s novel is certainly ripe for that. But it frustratingly never goes too far in that direction, and when the children are offscreen and the adults become the sole focus, any spark is all too often lost.

UK | 2022 | 346 MINUTES • 7 EPISODES | COLOUR | ENGLISH

writers: David Farr, Sasha Hails, Namsi Khan & Laura Lomas (based on the novel by John Wyndham).

directors: Jennifer Perrott, Börkur Sigþórsson & Alice Troughton.

starring: Keeley Hawes, Max Beesley, Aisling Loftus, Ukweli Roach & Lara Rossi.