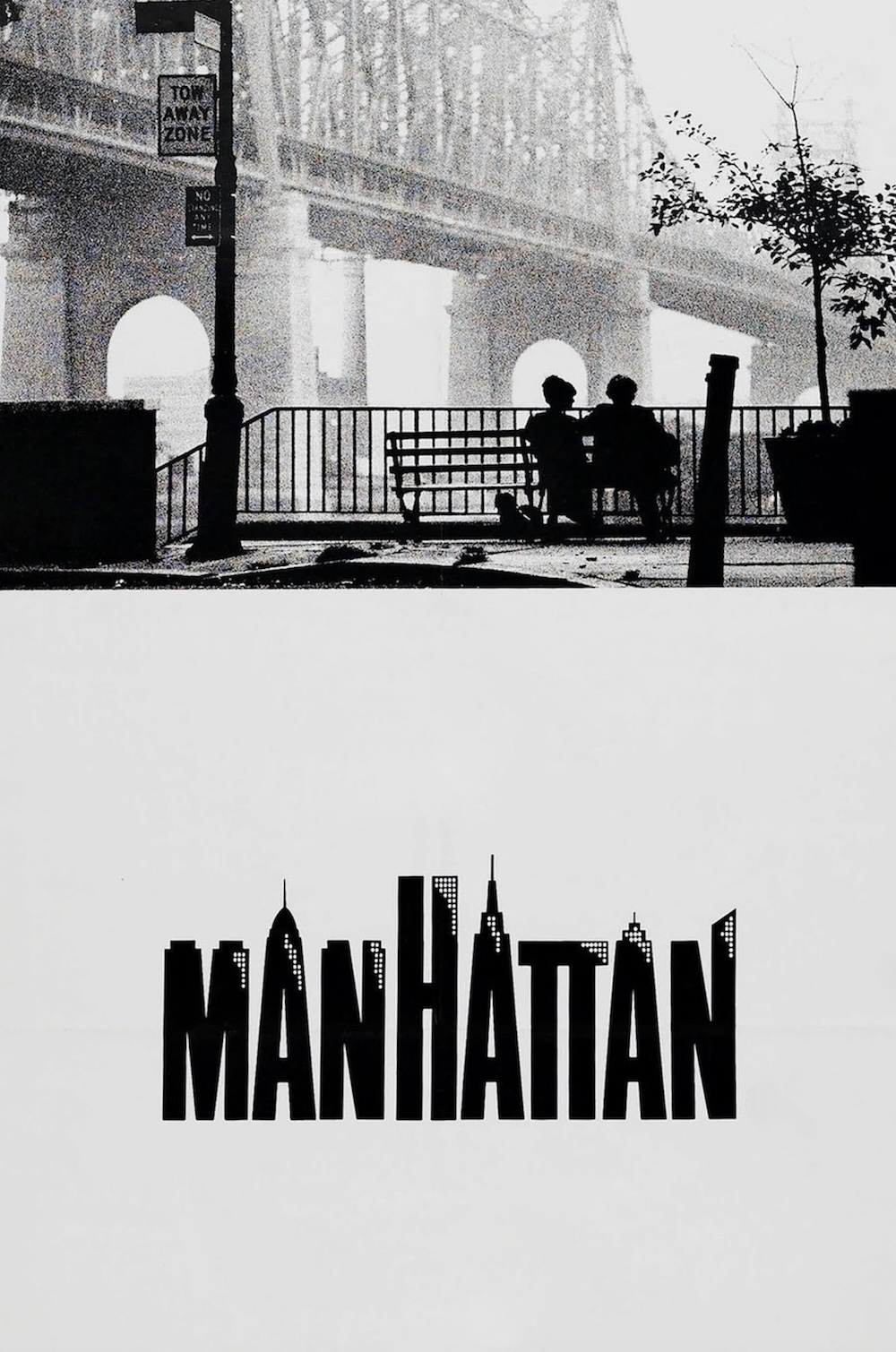

MANHATTAN (1979)

The life of a divorced television writer dating a teenage girl is further complicated when he falls in love with his best friend's mistress.

The life of a divorced television writer dating a teenage girl is further complicated when he falls in love with his best friend's mistress.

The opening notes of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” invite the world to bask in the majesty of a living, breathing space: New York City. The city that never sleeps is slowly roused from its slumber by a mellifluous clarinet—it’s morning, and the city is waking up. Skyscrapers, street corners, and shop fronts are bathed gently in sunlight, and we recognise, unmistakably, that we’re in Manhattan, a real place that’s also a figment of Woody Allen’s imagination.

Manhattan follows the life of Isaac Davis (Allen), a comedy writer for a television show that he loathes. He’s in a scandalous relationship with a 17-year-old, while his best friend Yale Pollack (Michael Murphy) is having an extramarital affair with a beautiful journalist, Mary Wilkie (Diane Keaton). Both romance and moral dilemmas are in the air, especially after Isaac and Mary develop feelings for each other.

Woody Allen’s Manhattan is a deeply resonant film, perhaps the most poignant of his entire career. It’s a story that explores both distance and intimacy, right and wrong. It’s a story about love, about the romances that flit by in our lives too quickly for us to recognise their significance, and the loneliness that throbs in between. But above all, what makes Manhattan Woody Allen’s masterpiece is that it’s a simple, moving tale about life, along with everything that makes it worth living.

As you might have guessed from my description of the narrative, there’s little in the way of a traditional plot. Much like the rest of Allen’s work, there’s just enough plot for the characters to become meaningful. The auteur’s writing has always been heavily focused on his characters, giving everyone on screen a generous amount of time to voice their various fears, anxieties, and incorrigible neuroses.

Fortunately for Allen, Manhattan is benefitted by the superb editing of Susan E. Morse, who never allows these sequences of ennui and existential crisis to become overlong. She wisely keeps the story moving, often cutting from one scene to the next with both efficiency and hilarious effect. Undoubtedly this is the result of a close collaboration between her and the director. Though Allen is famous for his shrewd writing ability (and often deifies writers and thinkers in his movies), it’s starkly evident that he writes as a filmmaker; his screenplay is full of amusing editing cues.

Undoubtedly, while he writes visually, he wouldn’t have been able to bring this film to life with the same visual flair as his cinematographer, Gordon Willis. The entire film is richly captured in stunning black-and-white, with superb shot selection. Aside from the haunting lighting–as employed in the now-iconic bench scene—there’s a commendable economy of movement in Willis’s cinematography. There are a couple of tracking shots where couples or groups walk and talk, but for the most part, Willis utilises only a few well-timed pans to capture everything we need to see.

This is because Manhattan is a film that mostly takes place in apartments. If nothing else, Allen’s film shows how much drama, humour, and vibrancy can be confined within a couple of rooms. That being said, it never comes close to being a chamber piece; the pacing is too slow, the plot devices too vague, and, most importantly, Allen himself wants to break free and capture the beauty of his beloved Manhattan.

It’s a style that’s been much imitated since his enormous success with Annie Hall (1977). In the following decade, Rob Reiner’s When Harry Met Sally… (1989) felt very much like Manhattan in colour. A more contemporary comparison can be drawn with Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World (2021), which is a bit like Manhattan if it were told from Tracy’s (Mariel Hemingway) perspective.

Allen’s contributions to cinema also seem to have influenced the likes of Wes Anderson and Noah Baumbach. Indeed, Baumbach’s The Squid and the Whale (2005) feels akin to Allen’s Interiors (1978). Of course, both of them are drawing heavily from Scenes from a Marriage (1973) by Ingmar Bergman, who just so happens to be Allen’s favourite filmmaker.

Besides Bergman, Manhattan makes explicit reference to some of Allen’s other heroes, such as Gustav Mahler, Groucho Marx, and Frank Sinatra. He also continues to think everyone in the world has their own personal psychiatrist and has read Freud from cover to cover. The unrestrained adulation of psychoanalysis is amusing–in one sequence, the “What would Jesus do?” is replaced by the rhetorical question “What would Freud say?”—but it’s also illustrative of how Allen writes his characters: brimming with existential angst.

Everyone in Manhattan seems neurotic. They have glaringly obvious defence mechanisms, or exhibit unhealthy coping mechanisms that are starkly apparent to everyone but themselves. Woody Allen is just as insecure, hostile, and world-weary as ever, while Keaton’s Mary is self-sabotaging, emotional, and belligerent. They are the yin to each other’s yin—both naturally reject their yang because they subconsciously deny themselves happiness.

There is also Yale, who incessantly cheats on his wife, while constantly reminding Isaac that he has never cheated on his wife seriously, at least. Meryl Streep plays Jill Davis, Isaac’s ex-wife who writes a deeply invasive tell-all book about their marriage; she is still bitter about when Isaac tried to run down her lover. In fact, the only character who seems even remotely mature is the ironically young Tracy.

Much like in a lot of Allen’s work, there’s a preoccupation with ethics. Isaac often quotes the moral philosophies of pre-eminent thinkers to help him out of a tight spot. Although it sounds pretentious (and perhaps it is, a touch), Allen never does it without making fun of himself. Isaac is labelled self-righteous by Yale, who proclaims: “You think you’re God!” Bemused, Isaac retorts: “Well, I have to model myself after someone!”

Despite his strenuous efforts to work through problems intellectually, Allen achieves little more than his colleagues, most of whom readily justify their lying, cheating, or inaction by claiming emotional upheaval. However, Allen recognises that this is simply part of human behaviour, no matter how much we try to evade our flaws through reason.

Towards the end of the film, Davis starts recording his idea for a short story: ‘An idea for a short story about, um, people in Manhattan who are constantly creating these real, unnecessary, neurotic problems for themselves because it stops them from dealing with more unsolvable, terrifying problems about the universe.’ Of course, the short story is the film we’ve just watched, the characters it contains no doubt real figures in Allen’s life.

Allen’s films often feel so personal because, much like Streep’s character, he has turned his own experiences into an art form. Manhattan is about beginnings and endings, about painful, heartbreaking discoveries and reaffirming realisations. Ultimately, what makes Manhattan so charming is that it’s a film about life. It chronicles the vicissitudes of an existence spent quietly—and sometimes explicitly—searching for happiness, in whatever form we think it might take. We’re likely to make mistakes in identifying it, but that’s just par for the course…

USA | 1979 | 96 MINUTES | 2.39:1 | BLACK & WHITE | ENGLISH

director: Woody Allen.

writers: Woody Allen & Marshall Brickman.

starring: Woody Allen, Diane Keaton, Michael Murphy, Mariel Hemingway, Meryl Streep & Anne Byrne.