LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (1962)

An English officer unites and leads diverse, often warring, Arab tribes during World War I in order to fight the Turks.

An English officer unites and leads diverse, often warring, Arab tribes during World War I in order to fight the Turks.

As David Lean’s monumental Lawrence of Arabia approaches its halfway point—as lesser movies would start to wrap things up before the end—T.E. Lawrence (Peter O’Toole) reaches the Suez Canal with his young Arab servant Farraj (Michel Ray). After their long trek across the desert, its cool water is a welcome sight, of course, and water is a persistent motif in Lawrence. One Arab leader even boasts of being “a river to my people.”

But it’s also a symbol of British colonial rule. And so it’s appropriate, at this place where the Arabian sands run up against the realities of western civilisation and commerce and politics, that an apparently routine question thrown across the canal at Lawrence and Farraj by a British soldier on a motorcycle sums up the single biggest issue of the film.

“Who are you?” the motorcyclist asks.

The line, dubbed by Lean himself, not only encapsulates the film’s key question (one which it never really answers)—screenwriter Robert Bolt said “the whole story of Lawrence is a man trying to find an identity for himself”—but it’s typical of this very literary and literate work, where the smallest exchange can be packed with unspoken questions, ripostes and new perspectives.

Certainly, Lawrence works more than adequately (and very lengthily) on the surface, as a straightforward tale of adventure and the stresses it puts on an unexpected hero. But taken at face value it tells us surprisingly little, and its full weight is only really felt with the benefit of prior knowledge about Lawrence, his personal history and his context.

Consider, for example, the scene shortly before this—one that’s often overlooked, in a film most widely remembered for a few breathtakingly spectacular sequences. Here, shortly before reaching the canal, the dust-caked Lawrence and Farraj stumble across a deserted, half-destroyed British fortress. Lawrence’s reaction is pensive, though Farraj doesn’t seem to understand why.

Any viewer might easily grasp this is a moment where the hard truth of war is coming home to him, but only those aware of the real Lawrence’s pre-war history (barely mentioned in the film) would surmise he’s also thinking of the medieval Crusader castles he’d studied as an archaeologist, and guess that he’s now pondering how the British Empire—or his own leadership of the Arab Revolt against the Turks—might come to the same crumbling end.

Consider, too, that the motorcycle on the other side of the Suez Canal is not coincidental (any more than the motorcycle passing by in the final scene will be). Like the ruined fort, perhaps, they’re reminders (for the audience) and unnoticed foreshadowers (for Lawrence) of mortality; because Lawrence begins with the character’s death.

Specifically, it begins with an overhead shot of a motorcycle. Lawrence (not yet identifiable as O’Toole) walks across the frame to the machine, fusses with it, and sets off through the English countryside, speeding in and out of light and shadow, a foretaste of both the character’s ambiguity and the exquisite photography by Freddie Young—which remains the movie’s most celebrated strength.

But Lawrence of Arabia juxtaposes violence with beauty here, for the first of many times, as he swerves to avoid two young cyclists and crashes; his goggles, hanging from a branch, were the last thing filmed by Lean. He died of his injuries some days later, but the movie takes this as understood and cuts instead to his memorial service at St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, in 1936.

Here, the “who are you?” question rears its head again in a different form, with distinguished attendees delivering up variations on the word “know” to a reporter seeking quotes: “He was the most extraordinary man I ever knew,” says one. “Did you know him well?” the reporter probes. “I knew him.” But whether any of them really knew him, or whether we will get to do so, is clearly open to question.

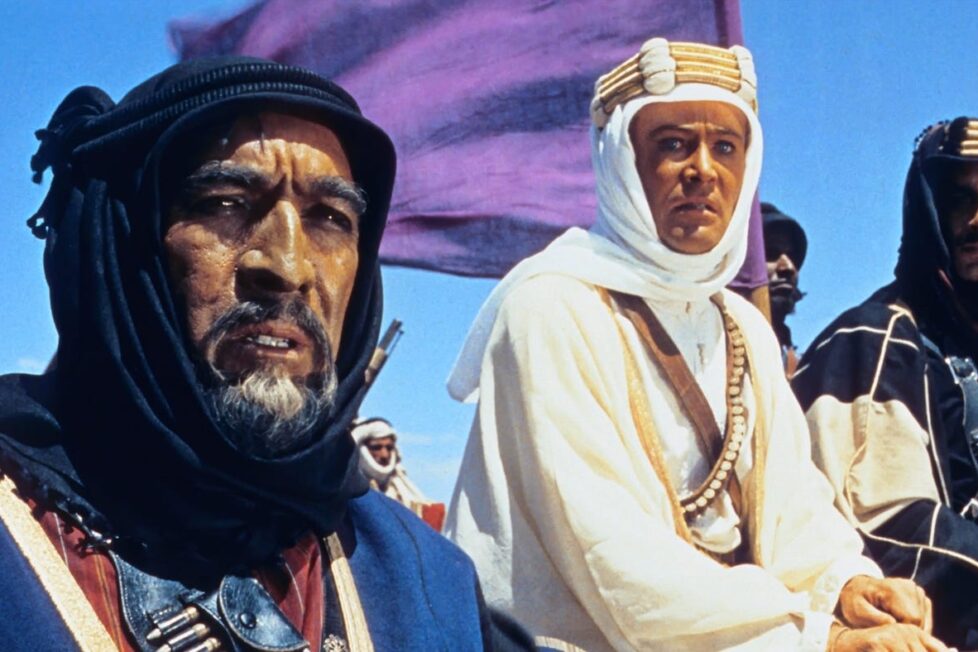

Before long, Cairo is mentioned, and Lean now cuts to the story that will occupy the rest of the film. We meet Lawrence, a junior intelligence officer in 1916, joking with a colleague and performing a party trick: putting out a match with his finger. “The trick,” he says, “is not minding that it hurts.” Not only an indication of the asceticism that he cherished, but a link to a much later scene where he does mind that something hurts, and finds it difficult to come to terms with.

Lieutenant Lawrence, despite his peculiarities (“you’re the kind of creature I can’t stand” says Donald Wolfit’s General Murray, maybe presuming Lawrence’s more effete and capricious side indicates homosexuality) now gets a field assignment. He’s to join the Bedouin, the nomadic Arabs of the Arabian peninsula, to appraise their military abilities and loyalties for the Arab Bureau, part of the British intelligence establishment.

The British are considering supporting the Arabs’ revolt against their colonial rulers, the Turks—who were also Britain’s enemies in World War I—and the British generals recognise the flexibility of an Arab army, used to cross the desert with minimal supplies, might give them an advantage over the westernised, mechanised, slower-moving Turkish.

But the generals and politicians are also worried: if the Arabs rise up successfully against Turkey, how likely are they to then accept British rule? This conflict—between the Arab desire for independence and the British plan to replace one colonial power with another—runs throughout the film, and the degree to which Lawrence is honest about it is a never-quite-resolved issue in determining how far he really sympathised with the Arabs, and how much he was simply using them for his own aggrandisement.

And so Lawrence heads for the desert, itself a major player in Lawrence of Arabia, introduced with one of the most famous images in all cinema: a very long-held shot, the lower part of the frame initially completely black, the upper shading from orange to yellow. It takes one a moment to realise it’s a sunrise, and then it dissolves to the dunes, and one can just pick out a tiny pair of men on camels. One of Lean’s most effective techniques in Lawrence (which he’d already explored in his 1952 aviation movie The Sound Barrier) is on display here: conveying the empty hugeness of the desert by shooting his characters from such a distance that they are barely visible.

Indeed, he even does it to an extent in the more constrained British HQ scenes—-the Officers’ Mess and offices seem almost unnaturally spacious, underlined in one shot by a map of the Arabian peninsula on the wall behind Mr Dryden (Claude Rains) and Colonel Brighton (Anthony Quayle). And the impression’s added to by the film’s immense running time; the duration of many desert shots becomes, in themselves, an expression of space.

So, already the flavour of the movie is emerging, and so too does more of the character of Lawrence. He refuses to drink water until his Bedouin guide does, despite his thirst (again, not caring that it hurts); and when the guide, Tafas (Zia Mohyeddin) asks of Britain “is that a desert country?” Lawrence replies “No. A fat country.” But then adds, “I’m different.”

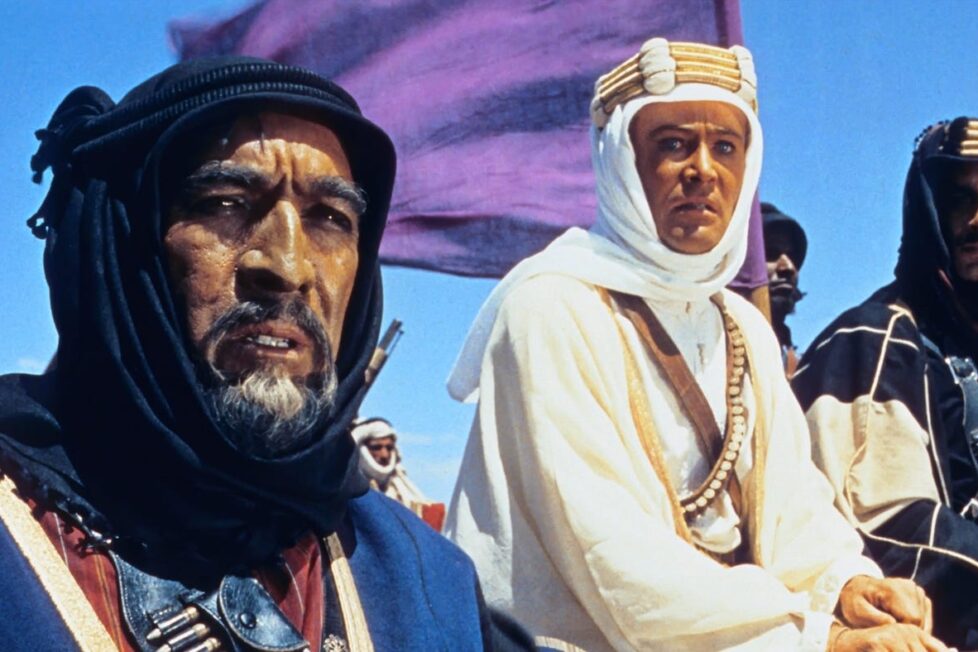

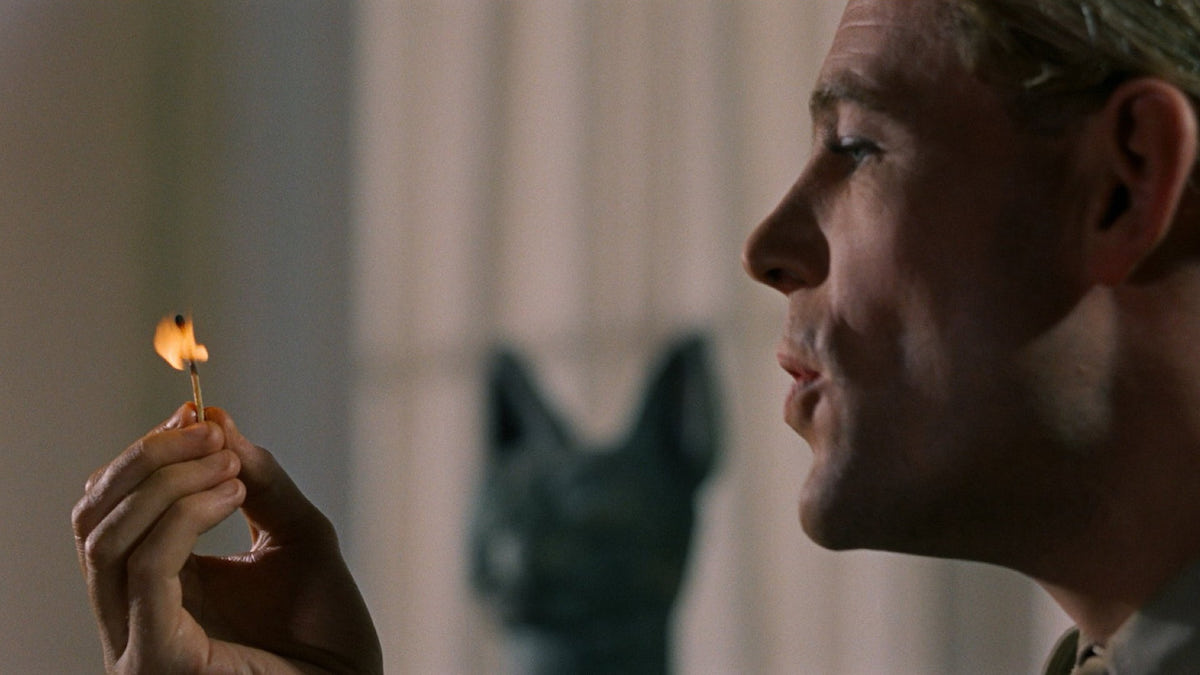

Soon there’s another tiny figure growing larger in the frame, in another of Lawrence’s most famous shots: the long silent approach of Sherif Ali (Omar Sharif), a Bedouin leader, who along with Auda (Anthony Quinn)—leader of another tribe—and Prince Faisal (Alec Guinness), will be one of the three main Arab characters in the film, and the one emotionally closest to Lawrence.

Lawrence himself becomes more Arab, too. He adopts the moniker “El Aurens”, and is given beautiful white robes which are such a contrast to his drab army uniform. There’s symbolism even in the costumes here: Lawrence’s British uniform was deliberately tailored for the film to fit badly, heightening the impact of his first appearance in local dress. But the Arab robes themselves are then gradually replaced with thinner and thinner, less and less impressive versions as the movie progresses, and the glamour and idealism of his early adventures are eroded by reality.

Lawrence has pretty much “gone native”, as the phrase then was, but he’s also different from the Bedouin with whom he now lives and is starting to lead in their revolt, and unify despite their rivalries.

He’s an outsider. “I have no tribe,” he observes. And when a fatalistic Arab says “it is written”, he retorts that “nothing is written.” Free now of the books that had filled his scholarly life to this point, he can make history as he pleases, he seems to believe. He may have delusions of grandeur, and Lean often shoots him as a messianic figure; when Auda incredulously asks him “you’ll cross Sinai?”, Lawrence replies “why not? Moses did.”

“They think he’s a kind of prophet,” says Brighton. “They do, or he does?” retorts General Allenby (Jack Hawkins).

Not all the Arabs are entirely confident in their unlikely prophet. Faisal, in particular, remains suspicious to the end that Lawrence’s true allegiances lie with Britain and not with his people. He and Ali also both, at different times, accuse Lawrence of playing with the Arabs, of secretly despising them as lesser; and there is certainly a nagging uncertainty throughout the movie as to whether Lawrence’s real dream is of Arab independence for its own sake, or of his being the man who gives it (his word) to them.

But while these themes rumble beneath the surface, much of Lawrence of Arabia is given over to spectacle: the landscape and the war. It’s quite old-fashioned, verging on gung-ho in its treatment of the latter; even the slaughter much later in the film of a column of retreating Turks shows little graphic violence, and Lean’s emphasis is on Lawrence’s own horror at his blood-slicked dagger, rather than on the dead. (It’s telling how different Lawrence of Arabia is in its tenor from Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem, which also dealt with WWI, and premiered just six months earlier. The film displays no real interest in the wider horror of war, beyond its impact on a single man.

Similarly, the first big set-piece of the movie is the attack on the Turkish-held port of Aqaba, which Lawrence and his Arabs successfully capture by crossing a forbidding desert that the Turks believed no one would venture into. Although the reality of the battle was much more mundane than Lean’s depiction, it’s a great sequence—yet one characterised much more by velocity than by violence.

Lean didn’t intend it as a war movie, anyway. He thought of it as effectively a love story with Lawrence and Sharif’s Ali as the protagonists. Certainly, their relationship is the most intimately drawn, and their final parting resembles the separation of quarrelling lovers. Earlier on, though, is the Arab boy Daud (John Dimech) and Lawrence who ride ecstatically toward one another as if hurtling into each others’ arms; Daud may represent the young Arab called Dahoum with whom the real Lawrence had a close friendship (and to whom the cryptic dedication of his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom may refer).

Questions of sexuality and sex, indeed, are often hovering around Lawrence of Arabia without ever quite becoming visible. Most notable, of course, is the sequence where Lawrence is briefly captured by the Turks in the town of Dera’a, and the local Bey (José Ferrer) as good as confesses (the appropriate word for 1917) his own homosexuality to Lawrence before ordering him to be beaten and—possibly—raped. The salacious idiot grin of the soldier holding him down during the beating points at this, as does the realisation on the face of Ali waiting outside; but the music suddenly covers whatever Ali is hearing.

Both this incident and any personal relationships Lawrence might’ve had with Arabs were difficult ones for Bolt and Lean’s film to tackle frankly; not only because of the times, but because details of his capture at Dera’a (did he exaggerate it or even make it up?) have never been certain, while Lawrence’s own sexual life (if he had one) has remained something of a mystery. The almost complete absence of women from the film, meanwhile, is surely nothing more meaningful than historical accuracy.

What is certain about the Dera’a incident is that it marked a turning point for the film and Lawrence; before, everything went well, but now nothing seems to. Earlier he told a reporter how much he appreciated the cleanliness of the desert, but now he’s thrown into the mud. “You have a body, like other men,” Ali tells him, but he is revolted by his own physicality.

He starts to reject the idea that he is a god-like figure and becomes almost obsessive about being normal. “Jolly good about the squash court,” he enthuses to a pair of fellow officers. But he can’t stop the blood from his torn back seeping through his jacket, and his attempts to fit in are clumsy. “Lays it on a bit thick, doesn’t he?” he overhears a colleague saying after the squash court comment.

There had been plans for a film about Lawrence long before Lean, despite the subject’s claim that “I loathe the notion of being celluloided”. The British director and producer Alexander Korda longed to pursue the project, but nothing came of it, although oddly Lawrence appeared as a villain in films from Stalin’s Soviet Union (1930’s Visitor from Mecca) and later Nazi Germany. Part of the problem was that by the 1930s Turkey was Britain’s ally, and there was little official enthusiasm for a movie that would portray them as the enemy.

But by the time Lean came to the project things had changed, not only politically but in terms of the perception of Lawrence too. The character had once enjoyed a Boy’s Own reputation, polished by the writer Lowell Thomas in his newspaper articles and his 1924 book With Lawrence in Arabia (Thomas is the model for the journalist Bentley in the film, played by Arthur Kennedy). But in 1955 Richard Aldington published his Lawrence of Arabia: A Biographical Enquiry, the first of what eventually became a small flood of books exposing a much more complex and flawed Lawrence.

The public was, thus, prepared for the idea that Lawrence wasn’t an unalloyed hero. All the same, Bolt—hurrying to get the job done quickly—based his screenplay largely on Seven Pillars of Wisdom, omitting or altering much detail. The character of Ali is a composite, for example, and so is that of Gasim (I.S Johar); and though Quayle’s Colonel Brighton is presented as the only other Briton with Lawrence and the Arabs, in reality, there were many more. Bolt also, of course, omitted nearly all of Lawrence’s life before and after the Arab Revolt.

Lawrence wasn’t an entirely reliable source in the first place and the filmmakers further massaged reality for dramatic purposes, so inevitably there were criticisms of inaccuracy. One of the most frequently made, bizarrely, is that O’Toole was much taller than the real man. For the most part, however, Lawrence of Arabia was received enthusiastically. The great British critic Dilys Powell wrote of the camerawork, “I think it is the first time for the cinema to communicate ecstasy”, while Alan Dent in the Sunday Telegraph called it “just about the best-looking film in the whole of my experience.”

Indeed, the stupendous 70mm Super Panavision visuals are surely the most impressive thing in the film—-more so than the acting—and they, along with Lean’s direction, must account for the high regard in which it is held by other filmmakers such as Steve Spielberg and Martin Scorsese.

Lean, termed by one critic the “poet of the far horizon”, and his photographers (including Nicolas Roeg in Second Unit) use the desert as lyrically and grandiosely as John Ford employed Monument Valley (Lawrence, which mostly takes place in modern Syria and Jordan, was filmed in Jordan, Spain and Morocco). But it’s not only the sand and rock which mesmerise: there are the brightly-clad horses and camels too, the flags, the splendour of Faisal’s cloak and sword

Maurice Jarre’s score also stands the test of time, complete with overture and entr’acte for the intermission. A long roster of better-known names had been considered: Bernard Herrmann, Malcolm Arnold (who wrote for Lean’s The Bridge on the River Kwai, another tale of a man driven by obsession), William Walton, Britten, Aram Khachaturian. Richard Rodgers even wrote some music which wasn’t used.

But it was the relatively obscure Jarre, mixing grand cod-oriental themes with more poignant passages, jaunty British militarism with moments much more reminiscent of the Hollywood western, who caught the movie’s own mixture of feelings so well. Just occasionally there seems to be too much, but then something is needed to fill the empty, silent desert minutes; and at many key points (for example the attack on Aqaba) it is not allowed to dominate. Gerard Schurmann, only credited with the orchestration, also contributed much more than that.

The acting stands up less well 60 years later. The young O’Toole, in his first major film role (one for which Korda had wanted Leslie Howard, and Dirk Bogarde and Albert Finney had later been mooted), is indubitably memorable: the intensity of his face and eyes suggest both Lawrence’s drive and possible instability, and he effectively captures the theatricality, the childishness and the femininity which led Noel Coward to quip about “Florence of Arabia”. But at dramatic moments there tends to be far too much histrionic torment in his performance, at least for modern tastes.

The casting of the Arabs is certainly not to modern tastes either—Guinness was, of course, white British, and Quinn was Mexican-American, although Sharif was Egyptian. But, even if Quinn’s proud and venal Auda is a bit overdone, both Sharif and Guinness excel in their roles (despite the latter’s peculiar accent). The remainder of the cast tends to be completely serviceable, but not individually memorable.

Lawrence of Arabia was career-changing for Sharif, O’Toole, and Bolt, and confirmed the stature of the already established Lean. But he made only three more films—the next classic, Doctor Zhivago (1965), featuring both Sharif and Guinness—but Lawrence of Arabia is generally recognised as his masterpiece. ‘Best Director’ and ‘Best Picture’ were among its seven Academy Awards, along with wins for O’Toole, Sharif, the writers, Jarre, and the cinematographer Freddie Young.

It’s a film in which certain facets are famous, others less so. It’s remembered mostly for O’Toole, for its cinematography, its battle scenes, and for the desert, more than for its political narrative, or the surprisingly abundant humour.

Few films have ever equalled its combination of epic scope with such a close-up personal portrait, though Franklin J. Schaffner’s Patton (1970) came close, as did Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi (1982) to an extent. It is a product of its period, however, and not just in the casting. While there isn’t the excess of oriental kitsch that often could afflict epics of the time, the portrayal of the Arabs as childish, quarrelsome and unsophisticated seems condescending now, and occasionally Lean can give in to melodrama.

But he always extricates himself: a scene where a character is swallowed by quicksand seems to be milked for all its worth, but then at its very close, the camera simply records grains of sand tumbling into the rapidly-filling hole. Nobody needs to say, here, that the desert has won.

A cynic might suggest that, in the end, it all adds up to sheer gorgeousness and some thrills. Certainly, it’s not as thoughtful as it might pretend, but it never could have been: all it could really do was raise questions and hint at possibilities. Lawrence is an impossibly difficult character to understand and was all the more so in the early-1960s, before the later more psychologically-oriented biographies. Lawrence of Arabia might convince us we are gaining insight, but we are left at the end of the journey little wiser than we were at the beginning.

What a journey, though. I first saw Lawrence of Arabia more than 40 years ago, and it remains as enthralling on the umpteenth viewing as it was then, a film that burns as bright as the desert sun with its sweep, its sense of place, its colourful detail, its arc of near-tragedy. It may not satisfy strictly as a biopic, and it may have dated. But it has certainly not dimmed.

UK | 1962 | 202 MINUTES (THEATRICAL CUT) • 222 MINUTES (UK PREMIERE CUT) • 227 MINUTES (DIRECTOR’S CUT) | 2.20:1 | COLOUR | ENGLISH

director: David Lean.

writers: Robert Bolt & Michael Wilson.

starring: Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, Omar Sharif, José Ferrer, Anthony Quayle & Claude Rains.