KUNG FU CULT MASTER (1993)

During the Yuen Dynasty, many sects compete for possession of the two golden swords which contain the secret to dominance of the world of martial arts.

During the Yuen Dynasty, many sects compete for possession of the two golden swords which contain the secret to dominance of the world of martial arts.

Those coming fresh to the Kung Fu Cult Master / 倚天屠龍記之魔教教主 story and the Condor Heroes mythos will be baffled by Wong Jing’s beautifully bonkers adaptation of just one dense chunk of the epic. Yet, for those willing to surrender to the magical martial arts madness and near non-stop wire-assisted wuxia action, it can still be enjoyed as a joyous last hurrah for Golden Harvest’s golden age.

There’s a dedicated cult audience eagerly awaiting this newly restored print, sourced from the original Hong Kong theatrical cut, making its UK Blu-ray debut on Eureka Entertainment’s esteemed ‘Classics’ marque. However, for those unfamiliar with Golden Harvest or requiring further wuxia exposition, the dizzying mix of lightning-fast stunt sequences, Chinese legends, anachronistic dialogue, raunchy innuendo, and cartoonish violence might prove altogether overwhelming.

The production and distribution companies under the Golden Harvest banner dominated the Hong Kong movie landscape throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Born from a breakaway group of renegade producers from the Shaw Brothers Studios, Golden Harvest carved its own niche. While both studios nurtured many influential action stars and directors, Golden Harvest made its mark in the early-’70s with a string of groundbreaking films starring the legendary Bruce Lee. This sparked a global kung fu craze, but the genre quickly became saturated with imitators. Recognising the need for innovation, Golden Harvest found the perfect solution: blending kung fu with other genres and remixing established tropes.

Despite being banned for periods, or at least ‘frowned upon’ in mainland China, the wuxia genre had been enjoying a renaissance in other parts of the Chinese-speaking world, particularly Hong Kong. Wuxia is a fantasy genre typically following a hero-quest template where the protagonist sets out to redress some injustice they have suffered. They endure a series of challenges as they learn magical fighting skills and test their resolve until, after various trials and temptations, they prove themselves worthy. It’s a very Asian storytelling format but can be described as a mix of ‘sword and chivalry’ with ‘sword and sorcery’ and is distinct from the broader martial arts genre. Outside of the Chinese-speaking world, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) is probably the best-known example.

The source material for Kung Fu Cult Master was Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre, the third in the Condor Heroes trilogy by Louis Cha, under the pen name Jin Yong—one of the authors at the forefront of the mid-20th-century wuxia revival. His interlinked historical epics garnered huge popularity when serialised in magazines and newspapers beginning in the 1950s. Heaven Sword and Dragon Saber was first serialised from 1961-63 in the international Chinese-language newspaper Ming Pao, for which Louis Cha was also the founding editor.

By the early-’70s, Cha had penned 15 long-form novels and was, by far, the most popular wuxia author and one of the most respected writers working in modern Chinese literature. His books appealed to a wide readership, particularly what would be categorised as Young Adult (YA), and became a cultural phenomenon—perhaps something akin to The Lord of the Rings but with the fantasy grounded in Chinese history instead of North European mythology.

Including three very successful television series, Wong Jing’s 1993 film was the seventh adaptation of the novel, though it only takes in its first half. So, here, we’re diving in at the deep end of the wuxia pool and climbing out before completing a full-length. The info-dense opening spiel of Kung Fu Cult Master is delivered so quickly that one doesn’t stand a chance of following the dynamics between the seven rival clans and their various leaders vying for ownership of the two swords of power. But, to a Chinese audience, these characters would be as familiar as King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, Robin Hood and his Merry Men, or Harry Potter and his Hogwarts schoolmates…

The film is set in the twilight years of the Mongolian-ruled Yuan dynasty as it gives way to the Ming, placing it in the mid-1360s of the Gregorian calendar. It was a time when different clans and factions were competing for territories, but the martial arts world of Kung Fu Cult Master is a parallel reality divided into two main factions—an alliance of six schools dominated by Shaolin and an ‘Evil Cult’ of four sub-clans including the dishonoured Ming.

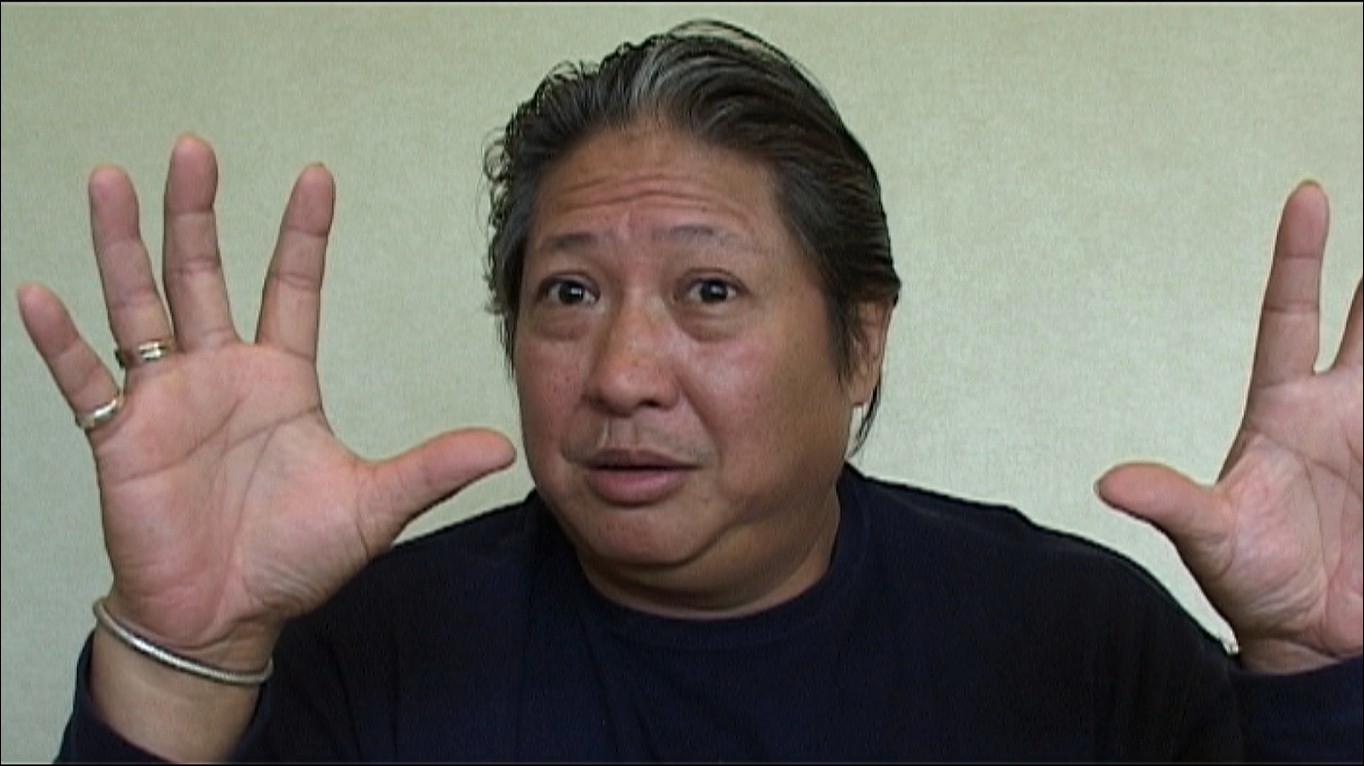

The Ming School was headed by the Golden-Haired Lion King, but it seems he ran amok with the Dragon Sabre and massacred many members of the other clans and is now in hiding. What set him on the rampage may’ve had something to do with another clan leader betraying him and murdering his entire family. But that’s all in the past when we join the narrative as the different clans gather to honour the Wu-Tang Clan’s master, Chang San-fung, (Sammo Hung) on his 100th birthday.

It all goes wrong when the gathering of clans realises that among the guests are two members of the Ming Cult travelling incognito with their young son, Chang Mo-Gei. They interrogate them with tragic results. Rather than give up the whereabouts of their Cult Master, Mo-Gei’s father literally explodes his own heart, spraying all those present with his blood. Mo-Gei’s mother consoles her son, tasking him with the duty of vengeance upon all those marked by his father’s blood before killing herself. The young lad is distraught and on top of losing both his parents, is severely injured by two freelance assassins who hit him with the Divine Palm punch which solidifies the chi within him, weakening him and preventing him from ever mastering kung fu.

Mo-Gei would’ve died if not for the intervention of Chang San-fung, who takes him in to be raised by the Wu-Tang. He later explains that the only known cure for the Divine Palm is to learn the Nine Yang Divine Stance but, unfortunately, he fought the last monk who mastered it, who then jumped off a cliff rather than admit defeat.

Here, kung fu isn’t a result of arduous training, but a form of magical power that can be acquired, passed on, and removed instantly, sometimes manifesting as a lurid yellow video effect. In other words, kung fu masters are wizards. The assembled clans aren’t really interested in bringing Golden-Haired Lion King to justice but want to acquire the magic sword he still has. A fierce character known as ‘No-Mercy’ or ‘The Abbess of Annihilation’ (Sun Mengquan) already has the other sword of power. At least she did, until unsheathing the Heaven Sword in the Wu-Tang courtyard. Master Chang San-fung deftly confiscates it, embedding it in the temple wall. Rather arbitrarily, he instructs her to send her best disciple to retrieve it after seven years have passed.

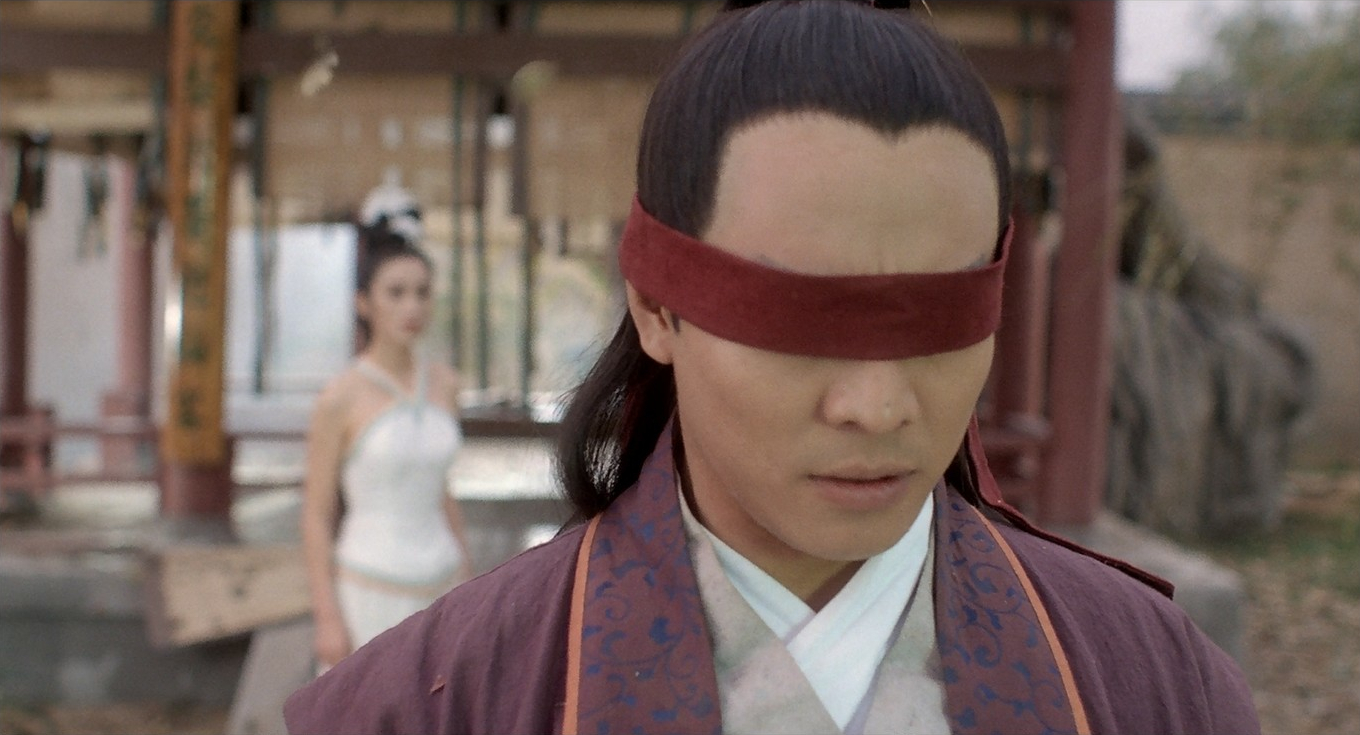

Seven years later, the adult Mo-Gei (Jet Li) has earned the enmity of top monk, Sung Ching Su (Colin Chou) who resents him for being Chang San-fung’s favourite even though he has zero kung fu prowess. While their master is away on a meditation retreat, Sung Ching Su encourages Chow Chi-yu (GiGi Lai), a representative of the Emei School visiting to collect the Heaven Sword, to use her womanly wiles to lure Mo-Gei into a situation engineered to provoke a fight that could lead to his death.

Mo-Gei’s innocence and total lack of confidence around pretty women get him into no end of trouble throughout. Luckily, another beautiful young woman, Tsu Chu, (Chingmy Yau), shows up out of nowhere and defends him using gravity-defying kung fu before they escape together but fall into a ravine. Before they can recover, they’re attacked by a mad monk embedded in a boulder who can control how it rolls with his powerful chi energy and perform kung fu with the animated vines that surround it. Turns out this is Huogong Toutuo (Huaili Yan) the monk who was thought dead after jumping off a cliff and, realising this, Mo-Gei tricks him into training him in the mysteries of the Nine Yang Divine Stance. This doesn’t take long and, quite suddenly, the effects of the Divine Palm are cured, and Mo-Gei has instant kung fu—finally, he’s ready to avenge his parents. How’s that for a set-up?

In the original novel, Mo-Gei falls down the ravine as a child and spends years in a cave learning the technique. The time-saving invention of the boulder-bound monk was a deliberate homage to a similar character in Tsui Hark’s Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) an influential wuxia classic made a decade earlier and shot by the same cinematographer, Bill Wong, who’d already worked with Jet Li on Tsui Hark’s Once Upon a Time in China (1991). Generally, he does a great job for Wong Jing and one can imagine the logistics of lighting some of the complex wire-fu action. The excessive use of wires to enable impossible flying leaps means that the wires are often clearly visible, all the more so in this high-definition print!

Apart from two recurring minor characters who deliver a constant stream of misogynistic remarks and poor-taste bawdy humour, the comedy core is provided by the vampiric Green-Winged Bat King, played for laughs by Richard Ng, who is at his best in scenes opposite Sammo Hung. Of course, Hung is one of the most respected stunt choreographers in Hong Kong cinema and wire-fu is a style he pioneered. He’s working on both sides of the camera here so, maybe we’re meant to glimpse those wires for comic effect. After all, this is a film that cannot be taken seriously, never approaching any semblance of realism.

One of the fight scenes plays on the theme of wires by having Jet Li balance on the extended strings of a koto that have been fired at him by Zhao Min (Sharla Cheung) a secret agent of the Yuan government. Although she seems to be a scheming villain, he can’t help but have feelings for her as she so resembles his mother. No surprise, as both roles are played by the same actress.

It’s a shame the frenetic pace never allows us to emotionally engage with the characters because the cast all put plenty of energy into their performances with Chingmy Yau managing some layered complexity as we learn that Tsu Chu may not be telling the whole truth about her background. With lean dialogue, she conveys her dilemma between following her secret agenda and admitting her genuine affection for Mo-Gei. They do share the one brief respite from the sound and fury when trapped in an ancient mausoleum where they must work together to solve a puzzle for Mo-Gei to acquire the undefeatable Heaven and Earth Shifting Stance and escape.

The non-stop action is the film’s central strength, but the storytelling is almost squeezed out between bouts of airborne acrobatics. So, things aren’t dull for a moment but, for those hoping for deeper connection, the fantastical kung fu fun could get in the way and become numbing rather than exhilarating.

One truly spectacular battle scene is so rushed it’s hard to tell who’s fighting who and what the outcome is, with clans circling and battling each other while Mo-Gei leaps over them, delivering balls of explosive chi energy from his fists as he flies. The staging of this complex battle involving cavalry being attacked by subterranean soldiers and an evil flying nun with a glowing sword, surrounded by hundreds of extras, with plenty of pyrotechnics and mechanical effects is astonishing. But it’s over too quickly to justify what must’ve been a huge chunk of a substantial budget reputedly exceeding HK$50M.

Nothing reaches a satisfying conclusion because the intended sequel was cancelled due to a disappointing reception and box office takings of just HK$10.4M. This considerable shortcoming has been blamed on various factors: the film is rather late jumping on the wuxia wagon; it’s one of several treatments of the same story but none had taken such liberties with the material, frustrating fans of the books; and it was playing against the big summer blockbuster, Jurassic Park (1993), so its visual effects would’ve seemed dated by comparison. Though now they add nostalgic charm.

Eventually, it managed to recoup a little bit more with several home entertainment releases under different titles—such as The Evil Cult, Lord of the Wu Tang, and The Swordmaster—accruing a cult audience over the decades. Nearly 30 years later, Wong Jing finally got to conclude his epic. After a reboot, New Kung Fu Cult Master (2022), he delivered New Kung Fu Cult Master 2 (2022), both starring Raymond Lam and released via streaming services over the Chinese New Year period. Whilst part one, with Donnie Yen filling Sammo Hung’s shoes as Chang San-fung, was well-received, I doubt it can ever match the fervour and inventive insanity of the 1993 version. Sadly, it seems that after all these years, and with the advantage of today’s digital effects, the conclusion made little impact with just a few mixed reviews and I am unaware of any planned international release.

HONG KONG | 1993 | 103 MINUTES | 1.78:1 | COLOUR | CANTONESE

director: Wong Jing.

writer: Wong Jing (story by Louis Cha).

starring: Jet Li, Sammo Hung, Sharla Cheung, Gigi Lai, Chingmy Yau, Francis Ng, Sun Mengquan, Bryan Leung, Collin Chou & Richard Ng.